| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Roosevelt's visit to Yellowstone continued, John Yancey, Yellowstone Jack Baronette. |

|

| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Roosevelt's visit to Yellowstone continued, John Yancey, Yellowstone Jack Baronette. |

|

|

|

|

About This Site |

|

From Gardiner, the presidential entourage headed out to Fort Yellowstone at Mammoth Hot Springs accompanied by a phalanx of military and cowboys with the naturalist John Burroughs in an army ambulance. Mr. Burrough wished that he would have at least been given a choice of the ambulance or horse. Writer's note, until about the beginning of World War I, ambulances were used not only for the transport of the injured or ill, but for ordinary transportation. Later on the trek about the park, Mr. Burroughs used a horse even though he had not ridden in nearly 50 years.

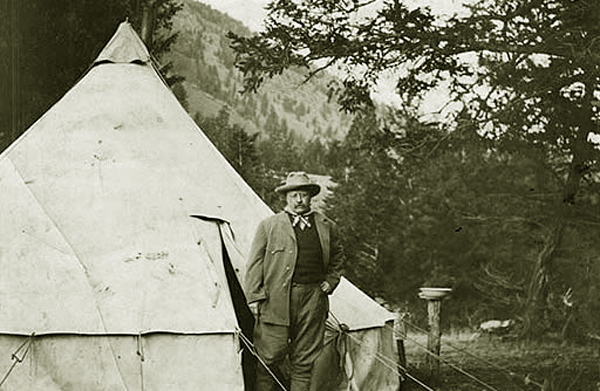

Theodore Roosevelt outside his tent, Yellowstone Park, 1903 The President was guided though the park by Major Pitcher. The presidential entourage included John Burroughs,guide T. E. "Billy" Hofer, Harry W. Child (1857-1931) of the Yellowstone Park Association, two orderlies , two cooks, and a crew to take care of the pack wagon and horses. The president's secretary was left behind at the presidential train to which telegraph lines had been connected in case of urgent business. As Mr. Burroughs noted in his 1906 "Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt:" The President wanted all the freedom and solitude possible while in the Park, so all newspaper men and other strangers were excluded. Even the secret service men and his physician and private secretaries were left at Gardiner. He craved once more to be alone with nature; he was evidently hungry for the wild and the aboriginal,—a hunger that seems to come upon him regularly at least once a year, and drives him forth on his hunting trips for big game in the West. The President was not completely out of touch with the World. On at least one occasion he had to deal with a major crisis at the White House. Mrs. Roosevelt was upset that some of the staff were playing catch on the White House lawn. See Smith, Ira R. T. with Joe Alex Morris: Dear Mr. President, Julian Messner, Inc., New York, 1949, p. 61. The presidential tent was a "wall tent." The others used a Sibley tents. For discussion of Sibley tents, see Fort Bridger. Roosevelt had taken an early interest in the west and owned a ranch in Dakota Territory. In 1885 he published his Hunting Trips of a Ranchman which was reviewed by George Bird Grinnell in his Forest and Stream. In the review Grinnell commented about Roosevelt's "limited experience." The review got Roosevelt's immediate attention with Roosevelt demanding an audience with the intrepid Grinnell. Whatever happened at the interview, it led to a friendship between the two. Roosevelt was also, as a result of his connections to the west and Wyoming, a friend of Owen Wister and Frederic Remington whose sketches of cowboys from Roosevelt's book are used on the top of this page. Roosevelt, in fact, employed Remmington on the ranch in Dakota.

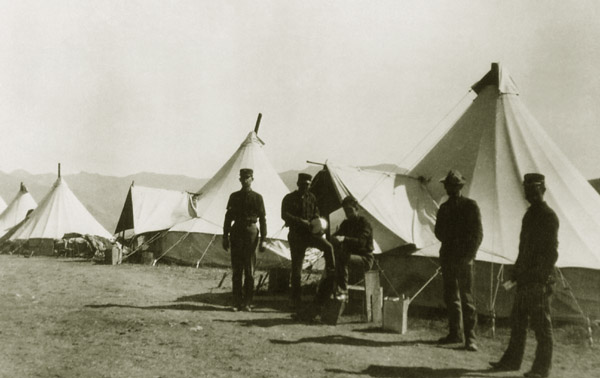

Presidential camp, Calcite Springs near the lower end of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1903. After camping on the Yellowstone River, seeing Hell Roaring Creek and camping at Slough Creek, hiking amongst the elk, the presidential party camped at Tower Creek Falls from April 14 until April 16. The camp at Tower Creek Falls was near present day Roosevelt Lodge which later took its name from its proximity where President Roosevelt camped. The trip to Slough Creek was apparently intended to get in some fishing. Unfortunately the creek was frozen over.

Presidential camp, Yellowstone Park, 1903. Roosevelt had previously hunted in Jackson's Hole and used Tazewell Woody as a guide. [Writer's note: Woody's first name is variously spelled "Tazewell" and "Taswell."] Roosevelt’s adventures, recounted in his 1893, “The Wilderness Hunter,” gave rise to a cowboy doggerel at the time of the Spanish American War in praise of Roosevelt and his guide:

Do you know Yancey’s? When the winding trail

A handy bunch of men round the stove

And Yancey he says: “Mr. Woody, there,

But Woody is a guide who doesn’t brag;

“That man won’t slosh around in politics

Now down at Yancey’s Every Man’s a sport,

Company "D," Minnesota National Guard, in front of Yancey's, 1893, looking east. The troops are being guided by F.J. Haynes riding "Rock." The horse behind Haynes is "Rye." At the time, Yancey's was on the main road from Cook City to Mammoth. The road has since been moved.

Pleasant Valley looking east, 2013. Photo by Geoff Dobson. Except for some remains of a foundation, all traces of Yancey's have disappeared. The area is used for chuck wagon dinners. On the south side of the valley is a small pavillion and several euphoniously named "vault toilets," i.e. privies. At the time of the writer's most recent visit, the privies were very much in the need of a good dose of lime. From within in addition to the emission of the aroma, there was the sound of a young lad screaming in terror. The grub is brought to the site in a modern horsedrawn chuck wagon.

Modern-day chuckwagon, at Yancey's, 2013. Photo by Geoff Dobson. John F. "Uncle John" Yancey (1835-1903) was born in Barren County, Kentucky. In 1851, Yancey left home and came west where an uncle had engaged in the freighting business. In the 1854's, Yancey traveled to California and bunked for a while with the famed mountainman and scout Jim Beckwourth. Yancey returned east, however, to enlist in Confederate forces. Following the Civil War, he appeared in Montana and then lived with the Crows from 1871 to 1877 before establishing his roadhouse sometime prior to 1880 as a squatter. His status was made legal when he was granted a lease of 10 acres surrounding the facility.

The hotel generally received less than rave reviews. The hotel had five or six rooms for guests reached by a creaking stairway made of rough sawns boards. The room numbers were marked in chalk. The cracks between the logs in the various rooms were covered with old newspapers. One early traveler, Carl E. Schmide, commented, "The beds showed that they were changed at least twice, once in the spring and once in the fall of the year." The bathing facilities consisted of an unchinked log structure with no door. Each room was, however, equipped with a washbowl, pitcher and part of a towel. In addition to the main building a saloon was housed in a second building. After, Yancey died in 1903, his nephew took over the operation of the hotel. The hotel burned in 1906. The saloon building was saved but at the expiration of the ground lease, the Park Service refused to renew the lease. The building was razed in the 1960's and today only traces of the foundations remain. Some travelers were perhaps overly fastidious. Burton Holmes in Vol. 6 of his Travelogues commented: A visit to "Uncle John Yancey's ranch is an experience that will be remembered but which will not be repeated. Yancey was present for Roosevelt's dedication of the arch at the entrance to the park but died a month later. Several guides periodically made their headquarters at Yancey's including Roosevelt's guide, Tazewell Woody. Woody (c. 1832-1916) might be referred to as the last of the great guides. He and Yancey were personal acquaintances with Jim Bridger and James Pierson Beckwourth. He was reticent to talk of his adventures. Roosevelt described him as "a very quiet man, and it was exceedingly difficult to get him to talk over any of his past experiences. Philip Aston Rollins also noted Woody was a man of few words Rollins wrote of an instance where Woody was hunting for mountain-sheep: The men had reached the summit of a peak the moment before the morning sun rose from behind another peak, and shot a golden pathway across the intervening field of snow. Woody's companion, with eyes glued to binoculars which were pointed elsewhere, said at that climactic instant: "There's a big ram," and was answered: "Shut up. God's waking.Rollins attributed Woody's lack of loquaciousness as a western characterisic of not opening up to strangers. What little we know of Woody primarily comes from Roosevelt's various books and magazine articles and from Rollins , The Cowboy HIS CHARACTERISTICS, HIS EQUIPMENT, AND HIS PART IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE WEST, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1922. Rollins, himself, was like Roosevelt a New Yorker, Ivy League (Princeton class of 1889, Columbia Law School and admitted to the New York Bar, 1895). and a prolific writer. Although eastern educated and kenw Latin at age 5 and Greek at not quite 8, he spent considerable time on his father's ranch in Montana. At age 5 he was left in the care of Jim Bridger for four months. Twice beginning at age 12 he was trailing his father's trail herd from Texas to Wyoming. In Yellowstone, Rollins used Woody along with John H. Dewing of Montana as a guide.

Woody was born in Missouri, drifted west ultimately to California where Beckwourth was then living. By 1870, he was in Montana. Over the years he was a a scout, worked for the army, and prospected for gold and was involved in the discovery of gold near Cooke City. by 1889, he was acting as a guide in Jackson's Hole and in the Yellowstone area. He and Dewing were expert trackers. Rollins noted one occasion in 1889, when the two were hunting near Jackson's Lake when word had come of a murder near Sargent's Ranch (See Grand Tetons). The wanted person was in the area. Within five minutes Dewing and Woody had picked up the trail. Rollins explained: Woody's was preceeded by his reputation for an ability to defend himself. Rollins relates the incident of a man who was hunting for Woody and rode his horse into a saloon, "'Has any gent here seen that feller Woody? I'm huntin' for him.' At that instant the man realized, for the first time, that Woody was in the room, and he realized also that, though he himself was facing Woody's back, the mirror negatived this advantage. He saw that right hand hanging idly down. Woody did not move a muscle. The man's jaw dropped. He remained quiescent for a few seconds, then backed out through the doorway, and on his own initiative rode out of the State" By 1900, Woody had moved back to Missouri and died there in 1916. Prior to his 1903 trip to Wyoming, Roosevelt had expressed concern about the depredation of large game by mountain lions and had proposed that they be exterminated. In planning his trip he first thought about hunting mountain lion in the Park. On reflection, however, he decided that hunting in the Park would not be perceived very well, particularly in light of the Lacey Act, discussed on a subsequent page, which made the killing of animals in the Park illegal. Rather than bring a hunting guide as a part of his party, Roosevelt included the naturalist John Burroughs. Nevertheless, Roosevelt probably violated the Lacey Act when he caught a mouse which he believed might be a new species. The President skinned the house. Burroughs described the skinning of the house as very professional. See Burroughs, John: "Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt," 1906. The presidential mouse was dutiful sent off to Clinton Hart Merriam, chief of the U.S. Biological Survey and co-founder of the National Geographic Society. Dr. Merriam pronounced it not to be a new species, but one which had not been observed in Yellowstone before. Roosevelt, howver, may have discovered a new species. Dr. Merriam did not have available to him DNA testing which is now used to ascertain differences between subspecies. In January 1998, John Etchepare, president of the Warren Livestock Company, commented to the Cheyenne Rotary Club as to the possible presence in the state of Preble's meadow jumping mouse,

"I have never seen one in the 35 years I've spent on the lands owned by Warren Livestock, nor is it ever mentioned in ranch history. However, I just received reports on DNA testing done on a mouse now dead for seven years, and officials believe they have one suspect jumping mouse in Wyoming." It has been recognized that even experts have difficulty in telling the difference between the the western jumping mouse (Zapus princeps), the meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius), and one subspecies, the Preble's meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei), using morphological characters. There is, however, a possible morphological difference, the Preble's meadow jumping mouse, on an average, has a slightly smaller cranial size and its molars are, on average, smaller. Thus it has been proposed that the presence of the Preble's mouse be determined using mitochondrial and nuclear markers amplified by polymerase chain reaction using DNA from tissue samples. Several months after Etchepare spoke, portions of Crow Creek, Chugwater Creek, Horse Creek, and Bed Tick Creek in Albany, Converse, Goshen, Laramie and Platte Counties, on May 13, 1998, were declared to be possible habitat for the mouse and entitled to special protection. No definitive study was done as to the presence of the Preble's mouse in these counties. The western and regular jumping mice are not endangered. E. A. Preble is also noted as the discoverer of the dwarf shrew (Sorex namus) near Estes Park. There is also a Merriam's shrew (Sorex Merriami, Dobson, 1890). [Writer's note: No relation.] Just to the west of Yancey's hotel, there was a turn-off to Baronette's bridge.

Baronette's Bridge, approx. 1871. The bridge was originally built by John H. "Yellowstone Jack" Baronett (1827-1901?) in the winter of 1870. Until 1903 it was the only bridge across the Yellowstone in the Park, although as later discussed a ferry was operated by "Uncle Tom" Richardson. The bridge was partially burned by the Nez Perce, as earlier discussed, with regard to the Indian Wars in their unsuccessful flight to seek the protection of Queen Victoria. It was rebuilt by General Howard. To add insult to injury, General Howard used lumber taken from Baronett's house. The Bridge was again reconstucted in 1880 and finally razed in 1905.

Baronette's Bridge after 1880. Baronette was one of those larger than life colorful adventurers that young boys dreamed of becoming when reading dime novels. He was born into an apparently titled family in Scotland. He ran away to sea and jumped ship to join the California Gold Rush. Thereafter, he prospected for gold in Africa, Australia, and Colorado. He served as second mate on a whaling ship. He acted as a courier for Albert Sidney Johnston during the Mormon War. With the outbreak of the Civil War he enlisted in Confederate Forces in Texas. Later Baronette served with the Emperor Maximilian before coming to Montana in 1866. Not withstanding that he was a former Confederate, he served as a guide for George A. Custer and Philip H. Sheridan. He joined the gold rush to Nome, but his vessel was lost. In 1901, Baronette disappeared while traveling from Washington State to California. Six weeks after Baronette's disappearance word came that a relative had been killed in the Boer War. If Baronette could be found, he had inherited the title.

Next Page, Yellowstone continued. |