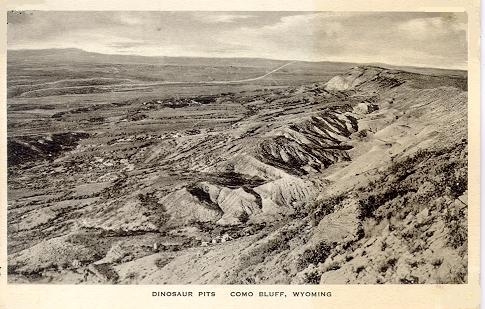

Como Bluff dinosaur grave yard, 1934

To the west of Rock River and to the east of Medicine Bow lies Como Bluff. In the popular mind, Wyoming may be associated with

Indian Wars, Range Wars, and Sheep Wars. Yet the Territory and Como Bluff was at the center of another

war which gripped the public's attention during the last third of the 19th Century, a war

which involved Indians, F. V. Hayden, John Wesley Powell, Yale University's

Peabody Museum, the Philadelphia Acadamy of Natural Sciences, and the Smithsonian. Indeed, echoes of that war

continue to reverberate today -- "The Bone Wars."

North Slope, Como Bluff dinosaur grave yard, 1934

In the 1860's paleontologists rarely collected their own specimens. It was common for collectors in the

field to send fossils to a paleontologist for classification. Dr. Hayden's fossils were classified by Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897).

Cope had been for a time a student of Joseph Leidy. Leidy, himself, about 1868, began receiving fossils from

two of Judge Carter's sons-in-law, James Van Allen Carter and Joseph K. Corson. Carter, not related to Judge

Carter, had married Judge Carter's daughter Anna and Corson married Ada. Corson was an assistant surgeon at Fort

Fred Steele and later post surgeon at Fort Bridger. In 1872, Leidy visited Fort Bridger and was taken into the forbidding Washakie

Basin by Carter and Corson. The Basin was described by Leidy as "an utter desert, a vast succession of

treeless plains and buttes, with scarcely any vegetation and no signs of animal life." Indeed, he

wrote, it was "undisturbed even by the hum of an insect." At the same time, Yale Professor Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1894) began a

series of expeditions into the west to gather fossils. In 1877, Railroad workers discovered large bones near

Como Bluff and notified Professor Marsh. Thus, it was discovered that while Wyoming may

have been scarce in living fauna, it was rich in extinct life. The competition, like the competition for the

last girls in a saloon before closing hour, was on between Marsh and

Cope. Each had egos larger than the Uintatherium robustum discovered by Leidy. The

uintatherium, named after the Uinta Mountains, was a eocene mammel looking much like a cross between a

hippopotamus and an elephant. Cope, in fact, thought it to be related to the elephant and, thus,

in a drawing put elephant ears on the animal. Both Cope and Marsh had more Uintatherium fragments

than Leidy and, thus, both attacked Leidy and each other. Leidy, caught in the middle between the two, withdrew

from further exploration in the West.

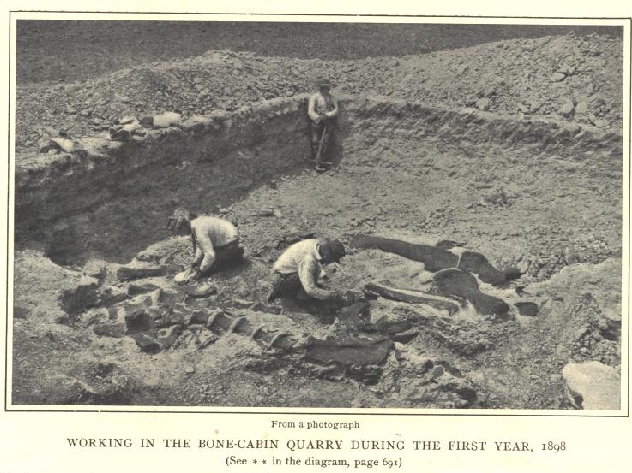

Excavation at Bone Cabin Quarry, 1898, Photo from Century Magazine, 1904

The Bone Cabin Quarry at Como Bluff took its name from

the fact that a cabin belonging to a local trapper was made of dinosaur bones.

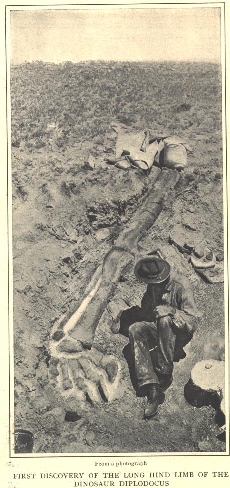

Diplodocus Leg and Foot, Como Bluff, 1898

Diplodocus Leg and Foot, Como Bluff, 1898

The Quarry, about ten miles from Como Bluff, was discovered in 1897 by Walter Granger (1872-1941). After 1903, Granger diverted his

attention to Paleocene and Eocene mammels. He primarily devoted his attention to Wyoming

from 1903 to 1918. Others who worked in the

area included Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh discussed below, and Barnum Brown, discussed with regard

to the Bighorn Basin. In one year alone, some 30 tons of dinosaur bones consisting of some

141 individuals were removed from the quarry.

Originally, Cope and Marsh were friends,

having met at the University of Berlin and having a common interest in the study of fossils.

Marsh established himself as a professor at Yale without teaching duties as a result of a

generous endowment by his uncle, George Peabody.

Cope was associated with the Philadelphia Acadamy and

relied on his own personal fortune. Following an expedition to Kansas in which both

participated, Cope assembled a skeleton of an Elasmosaurus, a marine

sauropod, and published a paper concerning his discovery. Unfortunately, Cope, in his haste

to announce to the world his new discovery, placed the head on the wrong end; that is, the

head was placed on the tail. When the error was discovered, Cope immediately began buying back at

his own expense all of the papers with the erroneous illustration. Marsh, however, not

missing an opportunity to enhance his own reputation, made sure the whole world knew of

his former friend's error and took delight in exposing Cope. Marsh sarcastically wrote that

Cope should have named the elasmosaurus "Steptosaurus," "twisted reptile."

[Writer's note:

Marsh made a similar error. It, however, was not acknowledged by the Peabody for more than 100 years.

Marsh placed the wrong head on a skeleton of a brontosaurus.

The Brontosaurus was used as a model for Brontosuauri all over the world. The error,

however, was not corrected by the Peabody until 1981 and required exhibits in

museums throughout the world to be changed.]

Additionally,

Marsh began bribing Cope's workers to send him, Marsh, new fossils from Cope's

fossil pits in New Jersey. The result was an animosity between the two. The animosity impacted on the U.S. Geological

Survey with each backing different candidates for Director, Cope backing Dr. Hayden and Marsh backing

John Wesley Powell.

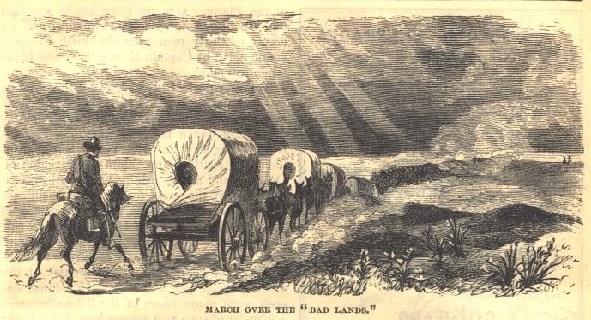

Marsh Expedition of 1870, engraving from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1871

Things boiled over, however, in Wyoming. Both Cope and Marsh conducted expeditions to the Territory; Marsh using the

military to provide protection against the Indians. Marsh used his influence interfered with Cope's ability to obtain

accomodations or assistants at Fort Bridger and Cope was required to sleep in the Fort's hay yard.

On Marsh's first expedition in 1870, Wm. F. Cody acted as

a guide for the first leg of the journey. Cody remained a life-long friend

of Marsh and would visit with him every time Cody's

show would play in New Haven. In 1879, Cope showed up at the Como Bluff accusing Marsh of

"trespassing" and stealing his fossils. Marsh directed that

the dinosaur pits be dynamited rather than allow fossels to fall into the "wrong hands." On another occasion,

Cope had a train load of Marsh's fossils diverted to

Philadelphia. Marsh, in turn, would attempt to delay Cope's work by salting Cope's digs with odd pieces of bone fragments unrelated

to the fossils from the period in question.

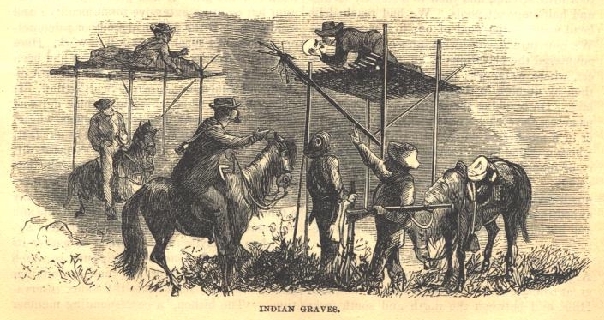

Indian Funeral Platforms, Marsh Expedition of 1870, engraving from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1871

On the expedition, Marsh crossed Lakota lands without permission in violation of the

1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie. Nevertheless, Marsh seemed unconcerned about the Indians. As indicated by the

above engraving, the expedition came across an Indian funeral platform, upon which rested the

bodies of a man and woman, beneath lay the skeleton of a pony. It was the custom of some

tribes of American Indians to place the bodies of the deceased on platforms with

tokens of respect such a food. Additionally, there might be sacrificed as a token of

honor a horse. After a period of time, some tribes would return and gather the bones of the

deceased. Marsh's attitude was indicated by his admonition to the students:

"Well, boys, perhaps they died of small-pox; but we can't study the origin of the Indian race

unless we have those skulls!"

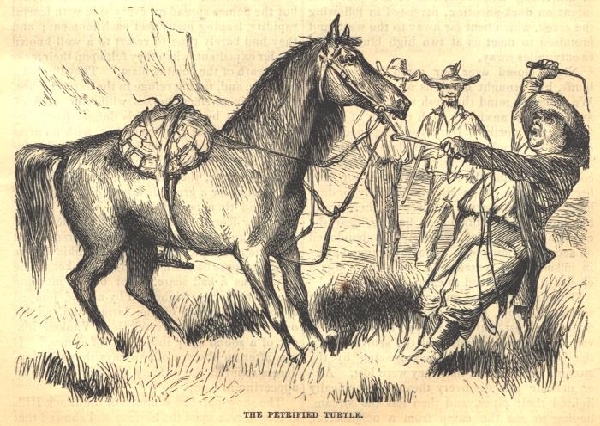

Turtle Fossil on Back of Horse, Marsh Expedition of 1870, engraving from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1871

Notwithstanding the concern by other members of the expedition as to ever more close smoke

from Indian fires ahead, Marsh seemed only concerned with the collection of fossils. In one instance,

he recovered the fossil of a giant turtle. While others wished to proceed in order

to avoid a confrontation with the Indians, Marsh's only concern, regardless of the reluctance of the

horse, was the exhibition of the turtle in his museum in New Haven.

Students Surprised by Snakes, Marsh Expedition of 1870, engraving from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1871

Other hazards faced the expedition. In one instance, while the students were bathing, an invasion of

snakes occurred.

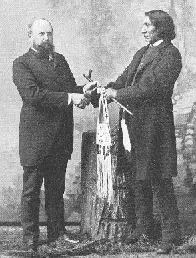

Red Cloud and Prof. O. C. Marsh, 1883

Red Cloud and Prof. O. C. Marsh, 1883

The Expedition was saved from being attacked by the Indians only

by the fact that Marsh had personally befriended Red Cloud by promising to

intercede with the Great Father on behalf of the Indians. Marsh kept his word. In 1883,

Red Cloud visited New Haven and called upon Professor Marsh. Red Cloud observed:

"I remember the wise chief. He came here and I asked him to tell the Great Father something.

He promised to do so, and I thought he would do like all white men, and

forget me when he went away. But he did not. He told the Great Father

everything, just as he promised he would, and I think he is the best

white man I ever saw."

Cope had a different way of dealing with the Indians. When visiting Indian

camps, he would amuse them by taking out his false teeth. The Indians were fascinated

by an individual who could remove and then replace his teeth. Cope was the more affable of the two. Behind his back,

Marsh was referred to at one of his clubs as the "Great Dismal Swamp." In contrast, one of

Marsh assistant's Arthur Lakes, from the Colorado School of Mines, was surprised to discover upon

meeting Cope, that Cope, rather than the Monstrum horrendum Lakes was expecting, was actually quite

friendly.

Marsh Expedition of

1870 Marsh Expedition of

1870

In total, Marsh personally conducted four expeditions into Wyoming between 1870 and 1874. After that time, members

of his staff would conduct the excavations and ship the fossils back to New Haven.

Pictured, left to right,

George Bird Grinnell, Bill the cook, Charles Wyllys Betts, O.C. Marsh (standing), Alexander Hamilton Ewing, Henry Bradford Sargent, Eli Whitney (grandson of

the inventor), Harry D. Ziegler, Charles T. Ballard, John Reed Nickolson, Charles McC. Reeve(? possibly John Wool Griswold), Charles Matson Russell. Grinnell later

became the senior editor and publisher of Forest and Stream which was

influential in the American conservation movement. Grinnell was invited by George Armstong Custer to accompany his

1876 expedition into the Black Hills as the expedition's naturalist. Fortuitously, Grinnell had another engagement and

declined. He also was the founder of the original

Audubon Society (discontinued in Jan. 1889) and is regarded as the "Father of Glacier National Park".

The animosity, nay, the hatrid one for the other, finally became public in January 1890. Cope had while on

federally financed expeditions gathered numerous fossils, spending some $80,000.00 in his own funds on

the effort. Nevertheless, in 1889 the federal government required that the fossils be turned over

to the government. Cope blamed Marsh who had been sucessful in obtaining the upper hand with the

Geological Survey. Thus, in an article in the New York Herald written by W. H. Ballou, a friend of

Cope, Cope blasted Marsh with both barrels. Marsh had written a monograph on the evolution of the horse. Cope

accused Marsh of stealing the work of Russian vertebrate paleontologist Vladimir Kowalevsky who had earlier

written on the same subject. He claimed that his rival's work was "the most remarkable collection of

errors and ignorance of anatomy and literature on the subject ever displayed." In one sense, Marsh did have a

remarkable collection of errors. Over the years, Marsh had been lovingly collecting every perceived error that

Cope had ever made.

The following week, Marsh responded in kind. Using his collection of errors, he claimed that Cope had committed "a series of blunders, which are

without parallel in the annals of science." Marsh indicated that when the first two had met in

Berlin, he suspected Cope's sanity. With regard to Kowalevsky, Marsh alleged that Kowalevsky "was at least

striken with remorse and ended his unfortunate career by blowing out his brains," but, Marsh continued, "Cope still

lives, unrepentant." In his haste to respond, Marsh was in error as to Kowalevsky. Although,

Kowalevsky committed suicide as a result of his penury, he did not shoot himself. He used

chloroform. While the public denunciations of each other were of short lived interest, the wounds inflicted by

Cope on Marsh had an ultimate impact. Marsh wrote and published at his own expense a monograph on toothed birds.

It was read by several congressman, with the result that Marsh was fired from his work with the

Geological Survey as an example of the waste of public money.

The end result of the Bone Wars was that each exhausted their respective fortunes. Cope had to sell part of

his collections. Marsh had to mortgage his house and beg Yale for a salary, the

endowment from his uncle having been spent. Today,

Cope is regarded as the more intellectual of the two, but is regarded as careless.

Marsh is considered to be the better politician and was more

careful in his work. Marsh has been accused of taking credit for the work of his students.

Echoes of the Bone War reverberate today. Today great controversy

exists among paleontologists as to whether birds are descended from

dinosaurs. The theory was first proposed by Marsh in 1877.

|