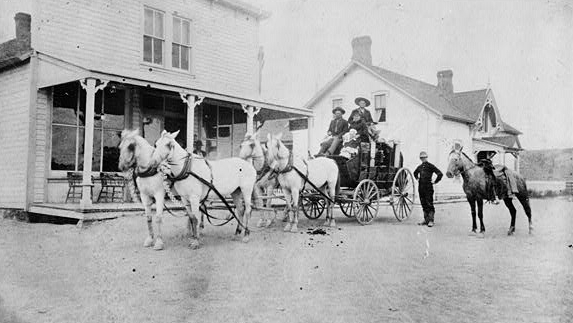

Deadwood Stage at Chugwater Station, 1884

The Above photo shows the Deadwood Stage,

with George Lathrop driver, at the home ranch of the Swan Land and Cattle Co. Ltd.,

in Chugwater. The sign on the porch immediately to the left of Lathrop indicates that

there is a public telephone. See close-up to left. Swan spent £1,000 to run

the telephone line from Cheyenne. The first telephone exchange in Cheyenne was installed

in 1881. The building to the right was the manager's house. The station

burned in 1918. Presently, the Swan office building sits on its site. George Lathrop (1830-1915)

arrived in Kansas in 1853. He subsequently made his living as

a bullwhacker, muleskinner and stage driver in Kansas, New Mexico, California,

Nevada, and Wyoming, surviving several Indian attacks. In one, he was the

sole survivor. In 1879, he was employed by Gilmer and Salsbury, the

operators of the Cheyenne and Blackhills Stage and Express Line. By the next year he was

driving six-horse coaches between Cheyenne and Fort Laramie. By 1882, he drove the

Fort Laramie to Rawhide Buttes run. He continued with the line after it was purchased by

Russell Thorp, Sr.

The Above photo shows the Deadwood Stage,

with George Lathrop driver, at the home ranch of the Swan Land and Cattle Co. Ltd.,

in Chugwater. The sign on the porch immediately to the left of Lathrop indicates that

there is a public telephone. See close-up to left. Swan spent £1,000 to run

the telephone line from Cheyenne. The first telephone exchange in Cheyenne was installed

in 1881. The building to the right was the manager's house. The station

burned in 1918. Presently, the Swan office building sits on its site. George Lathrop (1830-1915)

arrived in Kansas in 1853. He subsequently made his living as

a bullwhacker, muleskinner and stage driver in Kansas, New Mexico, California,

Nevada, and Wyoming, surviving several Indian attacks. In one, he was the

sole survivor. In 1879, he was employed by Gilmer and Salsbury, the

operators of the Cheyenne and Blackhills Stage and Express Line. By the next year he was

driving six-horse coaches between Cheyenne and Fort Laramie. By 1882, he drove the

Fort Laramie to Rawhide Buttes run. He continued with the line after it was purchased by

Russell Thorp, Sr.

See Maps of Deadwood Stage Road:

Crow Creek to Bordeaux (Hunton's Ranch)

Bordeaux to Rawhide

Rawhide Buttes to Robbers Roost Creek.

Use "Back" button to return to this page.

Deadwood Stage in front of manager's residence, Swan Land and Cattle Co., LTD, undated.

Photo by C. D. Kirkland.

Although not as

significant as the Overland

Stage, probably no stage line

has attracted more attention than

the Deadwood Stage, more properly, the Cheyenne and Blackhills Stage and

Express Line. The fame of the line and of Deadwood itself, was assured by being early featured in

Edward L. Wheeler's Deadwood Dick series of half-dime novels and Col. Cody's

Wild West show. Although it is doubtful that Wheeler ever traveled west of the

Mississippi, he described in lurid and inaccurate detail Deadwood and the stage. Thus, in

his 1877 Deadwood Dick the Prince of the Road; or the Black Rider of the Black Hills,

Wheeler introduced the stage:

Rumbling noisily through the black canyon road to Deadwood, at an hour

long past midnight, came the stage from Cheyenne, loaded down with

passengers, and full five hours late, on account of a broken shaft, which

had to be replaced on the road. There were six plunging, snarling horses

attached, whom the veteran Jehu on the box, managed with the skill of a

circusman, and all the time the crack! snap! of his long-lashed gad made

the night resound as like so many pistol reports.

The road was through a wild tortuous canyon, fringed with tall

spectral pines, which occasionally admitted a bar of ghostly moonlight

across the rough road over which the stage tore with wild recklessness.

Inside, the vehicle was crammed full to its utmost capacity, and

therefrom emanated the strong fumes of whisky and tobacco smoke, and

stronger language, over the delay and the terrible jolting of the conveyance.

In addition to those penned up inside, there were two passengers

positioned on top, to the rear of the driver, where they clung to the

trunk railings to keep from being jostled off.

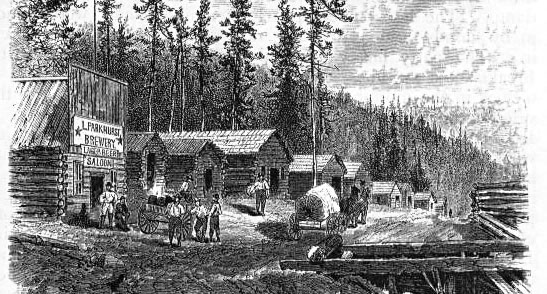

Deadwood City, 1877

And in the same manner from his imagination, Wheeler describes Deadwood City:

Deadwood is just as lively and hilarious a place during the interval

between sunset and sunrise as during the day. Saloons, dance-houses,

and gambling dens keep open all night, and stores do not close until

a late hour. At one, two and three o'clock in the morning the streets

present as lively an appearance as at any period earlier in the evening.

Fighting, shooting, stabbing and hideous swearing are features of the

night; singing, drinking, dancing and gambling another.

Nightly the majority of the miners come in from such claims as are

within a radius of from six to ten miles, and seldom is it that they go

away without their "load." To be sure, there are some men in Deadwood who

do not drink, but they are so few and scattering as to seem almost

entirely a nonentity.

Nevertheless, Deadwood City in its formative years tended to have a certain lack of

civility. The undertakers must have done a booming business. In addition to the murder of

Wild Bill Hikock by Jack McCall discussed on a subsequent page, others killed included

Myer Baum killed by Sam Young, bartender at the No. 10 Saloon; Pete Grant by

John Wingfield; Daniel Obrodevich by John Blair; and Peter Miller killed by

grocer M. Rosengarden for stealing chickens. 1878 was a banner year, 15 homicides and 5 suicides.

Indeed, one of those involved in a killing was one of Deadwood's founders, William Gay, after whom the adjacent camp of

Gayville was named.

Gayville, 1876. Photo by Stanley J. Morrow.

In 1878, Gay was charged with the murder of Lloyd Forbes. He defended on the

basis that the killing was excusable as an accident. Gay argued that as he was pistol whipping Forbes about the head, his revolver

accidentally went off. The defense was enough so that the jury found Gay only guilty of

second degree manslaughter. Gay appealed. But the Territorial Supreme Court was not very

impressed holding that there was not "the slightest testimony tending in the

least to justify or excuse the homicide." Territory of Dakota v. Gay, 2 N.W. 477, 2

Dakota 125 (1879).

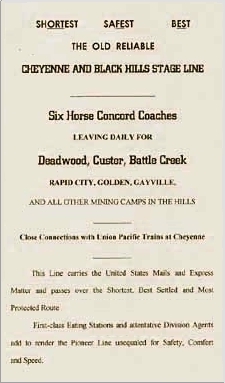

1877 Advertisement for Cheyenne - Black Hills Express Line

Following his release from the Detroit House of Corrections where, as did

Wyoming, Dakota Territory housed some of its prisoners, Gay ended up in Meagher County, Montana. In April, 1893,

a posse attempted to serve an arrest warrant on Gay and his brother-in-law, Harry Gross, for larcenies in Wyoming.

There ensued three shoot-outs with members of the posse. In the first shoot-out no one was hurt, but

Gay and Gross eluded the lawmen. In the second on May 8, 1893, Deputy Bill Rader was killed. Gay and

Gross again made good an escape. On May 11, another posse caught up with the

two on the Musselshell Rivr near Winnecook, Mont. In another shoot-out Deputy James Macke will killed. It took

two days for Macke to die in agony. Over the two days, Macke repeatedly claimed that he had been shot by Gay. Another witness confirmed that

the fatal shot came from Gay. With the wounding of Macke, the posse temporarily withdrew. When they returned,

Gross and Gay had made good their escape.

In 1895, Gay was caught in

The Needles, California, and was returned to Montana for trial. [Writer's note: Originally Needles, California, was

called "The Needles," the name derived from some sharp peaks down valley.] In Montana, not withstanding his

plea that the fatal shot was fired by Gross, Gay was found

guilty of first degree murder. On appeal, Gay also claimed that the jury was

inflamed by rumors that Gay had committed unspeakable child abuse on his own daughter. The appeal was

denied. The rumors had not been heard by the jury until after the guilty

verdict. Gay was hanged at the Lewis and Clark County Jail on Dec. 20, 1895.

The stageline was first owned by F. D. Yates & Co., owned by Capt. F. D. "Frank" Yates and W. H.

Brown, but was sold to the Gilmer and Salisbury Stage Co. in 1878.

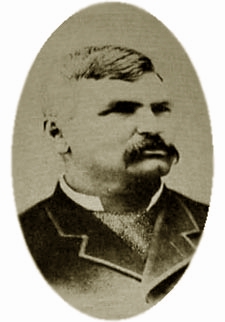

John T. Gilmer

The senior partner, John T. "Jack" Gilmer (1841-1892), started his career as a bullwhacker for

Russell, Majors & Waddell. Later he served as a stage driver for Ben Holladay and

as the agent on the Bitter Creek Division. After a making a fortune in

the express business, it was lost in mining. He died in the 1892 in Salt Lake

City. The ghost town of Gilmore, Idaho, was named for him. The Post Office,

in the establishment of a local post office, misspelled his name. His partner, Monroe Salisbury, was sued by the federal government in the

1890's, for fraudulent overcharging of the post office for express services in the

Dakotas and Montana.

In 1883, Gilmer and Salisbury sold the line to Russell Thorp who operated a livery stable

in Cheyenne. Thorp also had worked as a freighter for Russell, Majors & Waddell carrying

potatoes from St. Joseph to Salt Lake City. With the advent of the railroad, Thorp had briefly

gone into partnership with James Moore in Bear River City until the riot

(see "Hell on Wheels") ended any

hope of mercantile success in that city. Thereafter, Thorp moved to Evanston where he operated

a livery stable and was elected to the Unita County Commission. In 1875, he moved

to Cheyenne.

Deadwood Stage continued on next page.

|