|

Cabin at the KC

On the morning of April 9, 1892, Rueben "Nick" Ray (sometimes spelled "Rae") and Nate Champion, in the cabin depicted above,

were beseiged by an army of about 50 cattlemen and Texas hired guns who had come to

Johnson County to clean out "rustlers." The K C was not a large ranch. Its owner, John Nolan rented it to

Nate Champion who ran only about

200 head of cattle, far less than many of the large ranchers who belonged to the

Wyoming Stock Growers Association. Instead, Champion had been elected as the foreman for

upcoming May 1892 spring roundup of the newly formed Northern Wyoming Farmers & Stock Growers Association. The

Association had been formed by small stockgrowers in response to the

monoply of the WSGA. Champion had been elected even though

he had not attended its organizational meeting. The proposed spring round up was a month ahead of the

roundup scheduled by the WSGA.

Controversies relating to roundups and the intermixing of different herds were, of course,

nothing new. As an example, Nate Champion, himself, had been involved in disputes with

Mike Shonsey, foreman of Western Union Beef Company's E K outfit. The dispute arose when

Champion's cattle were mixed in with E K cattle. Shonsey promised to separate the two

brands. He did so by scattering Champion's cattle over broad distances on the

range. David Robb "Bob" Tisdale, a participant in the attack on the K C, took some of

Champion's calves. Champion and his men, in retaliation, returned the compliment. Tisdale, a well-to-do Canadian and son of

a member of Parliament, had an unpleasant streak about him. Tisdale owned the TTT on the Natrona - Johnson

County line and had come to Wyoming from Ontario about 1890. Owen Wister in his wanderings about

Wyoming was at first impressed by Tisdale. Tisdale had a first-class personal library, but Wister was turned off by a

display of cruelty. Wister wrote in his journal that he was with Tisdale when several horses got loose.

In the pursuit, the horse Tisdale was riding became winded. Even though Wister offered to swap horses, Tisdale

began beating and kicking his horse. Wister wrote:

"I saw Tisdale lean forward with his arm down on its forehead. He told me that he would kill

it if he had a gun but he hadn't. I watched him, dazed with disgust and horror. Suddenly

the horse sank, pinning him to the ground. He could not release himself, & I ran

across to him & found only his leg was caught. So I lifted the horse & got his leg out.

I asked him if he was hurt. He said no, & got up adding "I've got one eye out all

right." The horse turned where he lay, and I caught a sight of his face where

there was no longer any left eye, but only a sink hole of blood."As quoted by

Fanny Kemble Wister,

Owen Wister Out West, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Trouble between small ranchers and the owners of the larger holding had been brewing ever since the

disasterous winter of 1886. Problems arose out of the loss of open range. Larger

ranchers attempted to dominate the range by either controlling water or appropriating it for

themselves on a "customary use" basis. The Two-Bar, as an

example, acquired strategically located property fronting on the Chugwater and Sibylee Creek and, thus,

controlled large areas of open range in between. Others were more brazen. Frank Wolcott's Tolland Cattle Company simply

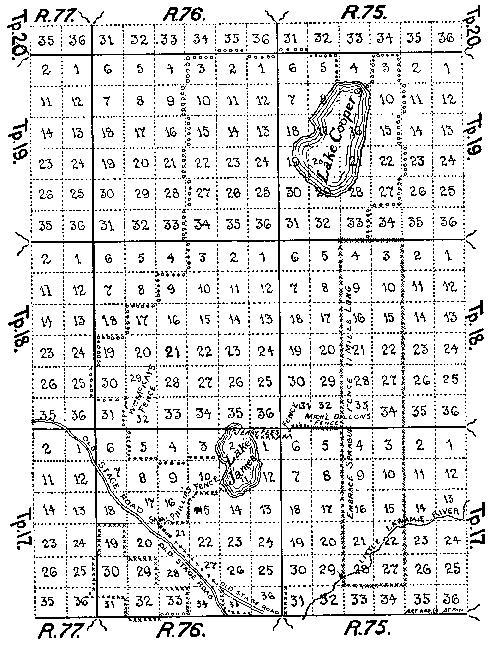

fenced in 15 square miles of government land. Another method of grabbing off open range was "checkerboard control," in

which the large cattle company would buy or lease alternating sections. As indicated in the map below,

Sections are numbered in a six mile by six mile grid so that odd numbered sections will always be

surrounded on four sides by even numbered sections and vice-versa like the red and black sqaures of a

checkerboard. By owning all of the odd or even sections, a cattle company could erect a fence along the borders of

owned sections and preclude access to the non-owned sections. In Wyoming perhaps the most famous example of checkerboard

control was the British-owned Douglas-Willan Sartoris Cattle Co. on the Little Laramie. As will be observed, the fence

is constructed primarily on the odd numbered sections owned by the cattle company.

Map of fence around holdings of Douglas-Willan Sartoris Cattle Co.,

Albany County, 1889.

The Douglas-Willan Sartoris Cattle Co., named for its two principals, John H. "Jack" Douglas-Willan (1852-1898) and

Lionel Charles George Sartoris (1863-1911) acquired from the Wyoming Land and Improvement Company various odd-numbered

sections and constructed fencing as shown in the above diagram. The fencing was constructed in the odd-numbered sections, four inches

in from the line. Each numbered section in the above-diagram constitutes roughly one square mile. At the section corners, the

fencing left a slight gap of about eight inches where the section marker was located. The effect was to fence in 200 square miles

of publicly owned lands in even-numbered sections. The scheme was held by the Territorial Supreme Court to

be legal. See United States v. Douglas Willan Sartoris Co., 3 Wyo 287, 22 P. 92 (1889).

The large ranchers contended that much of their losses were incurred because of

unbridled rustling by small "nesters." Among other things, it was contended that railroad contractors fed their crews with

beef purchased from the rustlers. Accordingly, cattlemen took matters into their own

hands. Among those hanged without trial were Jim Averell, the keeper of a modest

road ranch, and his wife

Ella Watson. Averell attracted the interest of large cattlemen when on April 7, 1889, he wrote

the Casper Weekly Mail of the cattle interests:

They are land-grabbers, who are only camped here as speculators in land under the desert land act. They are opposed to

anything that would settle and improve the country or make it anything but a cow pasture for eastern

speculators. It is wonderful how much land some of these land sharks own -- in their minds -- and how firmly they are organized to keep Wyoming from being settled up.

They advance the idea that a poor man has nothing to say in the affairs of this country, in which they are wrong, as the furture land owner in

Wyoming will be the people to come, as most of these

large tracts are so fradulently entered now that it must ultimately change hands and

give the public domain to the honest settler.

Tree upon which Ella Watson and James Averell were hanged, July 20, 1889, Spring

Canyon.

The murder was justified by claims that Averell and Watson were rustlers; that

Watson had been the inmate of a disorderly house; and that she was known as "Cattle Kate."

Some newspapers were aligned with the cattle interests. Thus the Cheyenne Sun wrote,

""The woman was as desperate as a man, a

daredevil in the saddle,

handy with a six-shooter and as adopt with the

lariat and branding iron." Watson was accused under the name "Kate Maxwell" of having robbed a faro dealer,

and having killed a black boy.

Ella Watson

Ella Watson

There really was a Kate Maxwell, a " working lady" of dubious reputation, possibly originally from Chicago

where she had worked in dance halls. The only diffiulty was that Ella Watson was not Kate

Maxwell. The actual Kate Maxwell worked in Bessemer to the west of Casper and about twenty miles from

where Watson and Averell lived. The "spin" put on the events by the cattle interests was, however,

successful. The name "Cattle Kate" has stuck.

In addition to Averell and Waton, Tom Waggoner, an alleged horse

thief, was hanged and his body left for the maggots in 1891. It was contended that

Waggoner had amassed a fortune of $30,000 to $70,000 from stolen horses, not withstanding, that he

resided with his wife in a two-room sparsely furnished cabin. One of the two rooms was an

atttached stable. There is also, perhaps, a lingering suspicion that Waggoner's death related to

alleged rustling from Elias Whitecomb's Standard Cattle Co. Tom Waggoner had loaned "Jimmy the

Butcher" money to establish his butchering business. When Jimmy was arrested for rustling Sandard Cattle

Company beeves, Waggoner posted Jimmy's bond. Jimmy also ended up dead. He was buried beside a house

belonging to a "cattle detective" working for the Standard Cattle Company.

One cowboy, John J. Baker, later recalled that some Texas guns had been brought in to get rid of

alleged rustlers:

There was one slaughter of nine old rawhides that were camped on Big Dry Creek near the

Carter Cattle Co.'s outfit. The men were trapping wolves for the hide and bounty as a

great many of the old waddies did during the winter. They were not rustling cattle and in fact

were out of the cattle business. A bunch of restler hunters made a surprise

attack on the camp and killed the nine trappers. They received the $450. bonus for the

slaughter and that was what they were after.

Nor were organized attacks by large stockgrowers on homesteaders limited to Wyoming. In Nebraska,

Isom Prentice "I. P." Olive, reputedly the wealthiest stockgrower in

Nebraska, organized efforts to drive homesteaders off the land culminating with the 1878 sadistic hanging of

homesteaders Luther M. Mitchell and Ami Ketchum.

The hanging was by stangulation rather than a drop. As

Mitchell and Ketchum strangled, they were burned alive with a fire lit beneath them. When the bodies

were discovered Ketchum was still hanging from an elm tree, his legs burned. Mitchell's rope had burned off but

one arm was still suspended upwards connected to Ketchum by a set of handcuffs. The other arm

was burned off to the shoulder. Olive was convicted of homicide but the Nebraska Supreme Court overturned the conviction on the

basis that the trial had to be conducted in the county in which the crime had been committed. Since

Custer County had not yet been organized, the trial had to be retried in a county court. The county judge

dropped the charges. Olive was like the fictional Liberty Valence and had killed at least nine men. Two, James Crow and

Turk Turner were caught skinning an Olive steer. They were tied up in the wet steer hide and left out in

the hot Texas sun to be crushed to death as the hide shrank.

After Olive was released from prison following the reversal of his conviction, he was stalked by

a father and son. In 1886, Olive having lost his fortune, was running a stable in Trail City, Colorado. On August 16, 1886,

in Haynes Saloon, Olive was gunned down by Joe Sparrow, a 26 year-old cowboy who allegedly owed Olive $10.00.

Sparrow's conviction in his first trial was overturned. A second trial ended with a jury deadlock and he

was acquitted in the third.

Illustration of the taking of Ketchum and Mitchell by I. P. Olive and his men

From A. O. Jenkins,

"Olive's Last Round-up" Sherman County Times c. 1930.

Other efforts were made to control small ranchers, "grease pots" as they were called, from branding as their own mavericks or strays. Cowboys

who were suspected of branding mavericks were blacklisted and precluded from

obtaining employment with any member of the WSGA. Small ranchers found difficulties in participation in the

roundups. Each roundup crew was known as a "wagon." In the 1883 Powder River roundup some

27 wagons participated, but by 1887 there were only four, the smaller ranches being eliminated. The blackballing

of the smaller ranchers from round-ups, however, backfired. The smaller ranchers simply organized

their own earlier round-ups and could thus brand and claim as their own all of the mavericks on the

range. Granville Stuart (1834-1918), for several years the President of the Board of Stock

Commissioners of Montana, later recalled one blacklisted rancher who did his own early roundup:

Near our home ranch we discovered one rancher whose cows

invaiably had twin calves and frequently triplets, while the

range cows in that viciinity were nearly all barren and would

persist in hanging around this man's corral, envying his

cows their numerous children and bawling and

lamenting their own childless state. This state of

affairs continued until we were obliged to call around

that way and threaten to hang the man if his cows had any

more twins."

Regardless of such efforts to stop rustling, the problem continued. In Johnson County, as

an example, there was the "Hole-in-the-Wall," wherein resided various outlaws who preyed on

cattle interests such as J. M. Carey's CY Ranch. Johnson County ranchers were predominately

small growers.

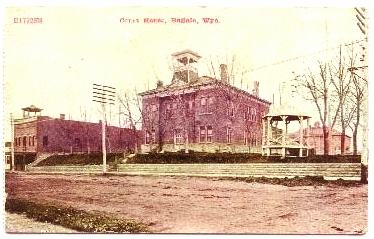

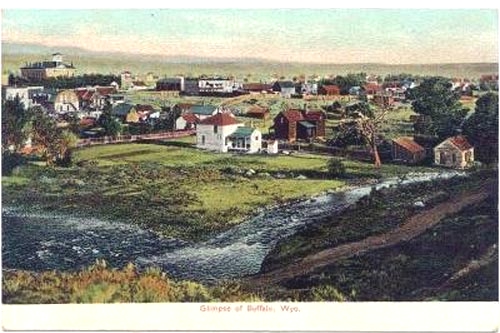

Johnson County Courthouse, Buffalo, Wyo.

Thus, a plan was devised by members of the

WSGA and the Cheyenne Club to send an expeditionary force into Johnson and Converse

Counties to clean out the rustlers. In November 1891, Thomas Calton Smith, a former deputy United States

marshal from the Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma), was employed to recruit a

force of gunmen from Texas. The Texans were promised $5.00 a day plus expenses. A $3,000.00 insurance

policy would be purchased for each and a $50.00 bonus would be paid for each "rustler" killed.

The plan called for a force of over 50 men to proceed to

Casper by train. From there, under the command of Deer Creek ranchman Major Frank

Wolcott (1840-1910), by horseback and wagon, the force would proceed northward to

Buffalo and replace the county government with individuals who would be more favorable to

the large cattle interests.

Second in command was to be English-born Fred Hesse, former foreman of

Moreton Frewen's 76 outfit. There was a certain degree of irony in the complaints by the larger

cattlemen. In addition to the Union Cattle Co. noted above, some had "mistakenly" applied an iron

to cattle they did not own. As an example, Arthur T. Corlett, the brother of one of Major Wolcott's

personal lawyers William W. Corlett, had been known to increase the size of his herds through

the use of an iron. Hesse, himself, had come up from Texas in 1880 as a cowboy. By 1882 while working for

Moreton Frewen, Hesse accumulated his own herd. Such "increase" in herds resulted in the tale allegedly told by

Bill Nye: "Three years ago a guileless tenderfoot came into

Wyoming, leading a single Texas steer and carrying a branding iron; now he

is the opulent possessor of six hundred head of fine cattle--the ostensible

progency of that one steer."

[Writer's note: The writer has been unable to find the original version of the story in Nye's books. The quotation comes from Earnest Stables Osgood's 1929 The Day of the Cattleman which

cites the Rocky Mountain Husbandman, June 14, 1883, as quoting the Laramie

Boomerang. The story has been repeated by numerous

writers. In the various versions, the herd has grown from 600 to 6,000. Nye did, however, in his 1887

Remarks allude to the growth of herds through the use of a branding iron in his reference to

"a cattle man, who had just moved on to the range with a government mule and a branding iron, intending to slowly work himself into the stock business."]

Hesse had a reputation in Johnson County as one not to be messed with. It was popularly believed, perhaps

mistakenly, that Hesse was behind the bushwhacking of local cowboys Orley "Ranger" Jones and

Johnny Tisdale. Jones had embarrassed Hesse in a local saloon. Tisdale had voiced opposition to the

large ranchers.

Buffalo, approx. 1890.

The plan called for telegraph wires into Buffalo to be cut in advance, so as

to preclude advance warning of the invasion. Allegedly, there had been prepared a "dead list" containing

the names of those to be eliminated. Various sources put the numbers of names on the

dead list between 30 and 70. Supposedly included on the list were Johnson County sheriff William

"Red" Angus, three Johnson County commissioners, and Northern Wyoming Farmers & Stock Growers Association roundup foreman, Nate

Champion. Additionally, Phil DuFran, former foreman for Sir Horace Plunket, was employed as a "cattle detective" to

go into Buffalo and act as a spy to provide intelligence to the invaders. DuFran had participated with

I. P. Olive in the hanging and burning of Luther Michell and Ami Ketchum. He turned state's evidence and

with the ultimate acquital of Olive never tried.

Buffalo, 1890's

Major Wolcott, manager of the Scottish-owned V R on Deer Creek and a one-time Converse County Commissioner,

received his military title in the Civil War. President Grant appointed

Wolcott as United States Marshal. In that capacity Wolcott also served as

warden of the territorial prison in Laramie City, but

was fired by President Grant after Grant was innudated with complaints that

Wolcott was obnoxious, hateful, "overbearing and abusive," and "insolent and dishonest."

His private life was allegedly "corrupt and disgraceful." See Larson, History of Wyoming, Second Ed. revised, p. 124. But

as observed by Professor Larson:

Such terms were, of course, mild in comparison with those which Johnson

County people would apply to him twenty years later when he was a

leader of the big cattlemen's invasion of their county.

Frank Wolcott

Frank Wolcott

Later Wolcott was a justice of the peace. On one occasion, Wolcott was allegedly beaten up. The assailant

was supposedly give a $40.00 suit for the deed. Nevertheless, Wolcott continued his reputation for

arrogance. An example of Wolcott's attitude as to legal niceties occurred

when Wolcott was servicing as justice of the peace. A poor musician who made his

living by playing in saloons for $2.50 a day

was brought before Wolcott on first appearance on a charge of grand larcency. The evidence was

wholly lacking and Wolcott was, thus, required to discharge the defendant. Nevertheless, Wolcott proceeded to

fine and imprison the defendant without trial and over the remonstrance of the prosecuting attorney. Justice Micah

Saufley of the Territorial Supreme Court explained what happened:

* * * Justice Wolcott, without any charge being made against Bachman, without

any evidence heard, without even the form or pretense of a trial, conceived

the idea of sending Bachman to jail for three months, and fining him $100,

on the supposition that he was a vagrant. I will here quote a part of the

testimony of Mr. Nichols, the prosecuting attorney in the grand larceny

examination, and a part of the testimony of Mr. Camplin, who represented

Bachman. The defendant, Wolcott, did not testify.

In reply to a question by plaintiff's counsel, asking what transpired at

the conclusion of the investigation of the larceny charge, Mr.

Nichols said: "He [Wolcott] said a great deal. He called the gentleman up,

and lectured him for quite a long time. He then made the remark that he was

going to sentence him to pay a fine of $100, and imprisonment in the county

jail at hard labor for three months, on the ground that he was a vagrant.

He said it was not probably just in accordance with law to do that.

Ordinarily, a man ought to be charged with that offense, but inasmuch

as the man was before him, he would waive the technicalities of the law,

and would assume the responsibility, and did not want any advice from the prosecuting attorney. Question. Did you attempt to advise him? Answer. I did. He said he was running that himself, and would take the responsibility. Q. Did you hear the defendant make a demand for a trial,--the defendant in that case and the plaintiff in this case. A. It is my recollection that his counsel demanded it, and I think the defendant said something about it, and objected to being sentenced without a trial, and wanted a trial. Q. Do you know whether or not it was refused by the defendant, Wolcott? A. Yes, sir; I know that he said he could not have any trial." In a few minutes after this extraordinary proceeding had ended. Nichols met the justice in front of his office, and remonstrated with him on the illegal course he had taken, and asked an explanation. To this Wolcott responded that they did not try cases in this territory according to law, but took a short cut sometimes; that he knew he had not followed the law, but he did it thinking it necessary,--the law didn't cut any figure in a case of

that kind. The attorney then tried to induce the justice to go back and

vacate the order he had made, but he refused, saying he would take his

chances; that he didn't like for men to live as Bachman, that it did not

make any difference about the law; that the county ought not to be put to

the expense of a trial; that he knew he had not proceeded according to law,

but he was going to teach Bachman a lesson, and was going to see that his

order was carried out. Wolcott v. Bachman, 3 Wyo. 335, 23 P. 673 (1890), dissenting opinion.

Next page, Johnson County War continued, the seige at the KC and the murder of

Nate Champion and Nick Ray.

.

|