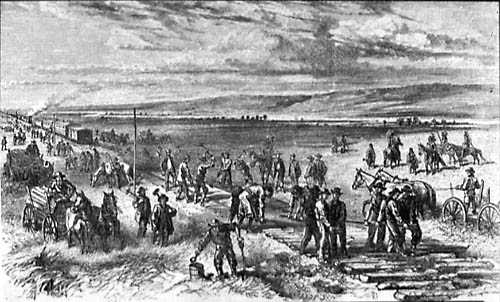

Building the Union Pacific, Nebraska,

Woodcut by Alfred R. Waud, 1867

For discussion of A. R. Waud, see Yellowstone. The construction of the

Railroad may be regarded as the centerpiece of Wyoming history. Indeed, the

Territory's first governor, John A. Campbell, noted that Wyoming was the first territory formed as

a result of a railroad.

Grenville M. Dodge, Chief Engineer Union Pacific Railroad

Grenville M. Dodge, Chief Engineer Union Pacific Railroad

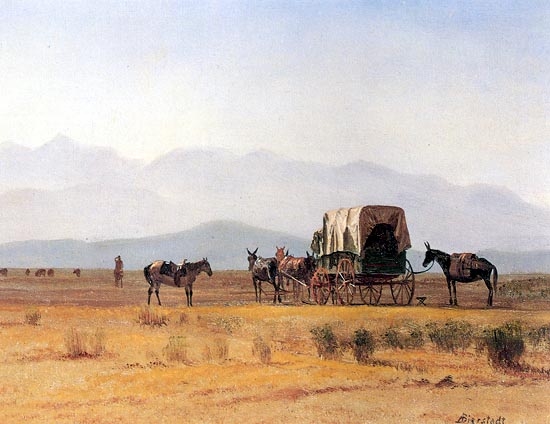

Plans and discussion for a transcontinental railroad linking California to the east date prior to 1853. Surveying for

possible routes by the military, as discussed with regard to G. K. Warren, began at the impetus of

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. Among those making repeated expeditions to the

west was a civil engineer, Frederick W. Lander(1822-1862).

Lander, a graduate of Norwich University, the first private engineering school in the

United States, worked for the Eastern Railroad of Massachusetts until joining

Isaac Ingalls Sevens survey expedition of 1853. The following year, he financed his own

surveying expedition. Of the six men in the expedition, only Lander and John Moffitt returned to

the Missouri, and Moffitt died two weeks later. There then ensued another three expeditions, the one of 1859 being the most

famous due to the presence of the artist Alfred Bierstadt. In 1861, Lander was engaged on a

secret mission behind Confederate lines into Texas on behalf President Lincoln. Thereafter, he accepted a commission

in the Union Army as a brigadier general. He died of a "congestion of the

brain" at Paw Paw, Virginia, in 1862. "Congestion of the Brain" was a 19th Century term used to

describe many conditions including hydrocephalus, stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, meningitis, and

sunstroke. Edgar Allan Poe was diagnosed as having died of congestion of the brain. For more see Lander.

Frederick W. Lander

Frederick W. Lander

The necessity for construction of the railroad

was clearly demonstrated during the Civil War. At the beginning of the war, Washington had

serious concern that the military commander of California, Albert Sidney Johnston, might turn California

over to the Confederacy. If such were to have happened the Union had no ability to transport

troops to the West. Johnston, however, did not turn California over to the Confederacy. Instead he resigned, remained loyally on his post until his

successor arrived and then returned to the South to

accept a commission with CSA forces.

Additionally, after the Trent Affair, British garrisons along the border between

British North America and the United States were strengthened, raising the specter of a war with

Great Britain at a time when the United States was otherwise preoccupied and the

American west coast was practically defenseless. Indeed, F. W. Lander, in his 1856 report to

Congress of his Reconnaissance of a Railroad Route From Puget Sound via South Pass to the

Mississippi River, presaged fear of British seizure of California as a reason for a railroad:

In the event of war with one or more of the great powers of Europe, California could not

be defended against aggression by the means then within the command of the

general government. Troops, supplies, and munitions of war would be

exposed to the dangers and costs of the inadequate modes of transit, of a

broken and interrupted water transportation, and to the passage of an unhealthy, and, in that

event, probably a hostile foreign territory.

Lander noted, "as is stated by the first military talent of the nation, California

cannot be practically defended by the means at present within the

disposal of government."

But at the same time, there was fear by the British that at the end of

the Civil War, no matter what its outcome, the Americans would turn on Canada. Thus, in the House of

Lords, the Earl of Ellenborough noted:

[I]n whatever manner the present civil war in America terminates--whether in the

success of the North, or in the South suceeding in establishing their independence--that is

whatever manner the present civil war in America terminates--the immediate result will be an irruption into

Canada? If the people of the North fail, they will attack Canada to obtain a

compensation for their loss. If they suceed, they will attack Canada in the

drunkenness of victory.

Debate, House of Lords, July 18, 1862.

Surveyor's Wagon in the Rockies, Albert Bierstadt, 1859

The lack of a supply line that a railroad would have provided,

resulted in the inability of the Confederacy to support its forces in

New Mexico and present day Arizona, leading, in part, to Confederate withdrawal from the west.

Lincoln strongly supported the construction of the transcontinental railroad and the

northern Congress took action making the building of the railroad following the war

possible. In contrast, the southern Congress was more concerned with north-south railroads.

Prior to the war, most railroads in the southern states ran from ports inland and did not

connect between the states. Thus, the southern Congress chartered a railroad company which undertook

the construction of a railroad connecting the various states. The effort was a success in that by

the end of the war, mail time from Atlanta to Richmond was reduced from more than a week to only

two or three days.

Ironically, while fear of war with Britain may have spurred on the transcontinental railroad, the

end of the Civil War and the construction of the railroad, resulted in a fear of annexation in

Canada. This, in turn, was an impetus for the formation of the Canadian Confederation and the

completion of the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Canadian fears were not without foundation. In

1866, H.R. 754 was introduced into the House of Representatives providing for the admission to the United States of the

"States" of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Canada East, Canada West, and the

organization of the Territories of "Saskathewan," Selkirk, and

Columbia. The Bill was referred to committee where it died. Indeed, Todd D. Sauvé in his 1997 Manifest Destiny and

Western Canada,

Book One:

Sitting Bull, the Little Bighorn and the

North-West Mounted Police Revisited, argues that the war on the

Indians and the construction of Fort Abraham Lincoln and the Northern Pacific Railroad were all part of a

sinister plot by Presidents Lincoln, Johnson, and Grant, aided by bribery and a

somnolent imperial government, to dismember British North America and annex it to

the United States.

Be that as it may, although, there have always been up until the 1930's a continent plan for such an

invasion, it is doubtful that any plan was viewed with any seriousness. The reduction of

size of the United States Army so that in the 1870's it was incapable of fighting two

Indian Wars at the same time, and the practical destruction of the United States Navy in

the years following the Civil War, made a war with Britain unrealistic. Even as late as the

1920's, American contingency planning was

based on the concept of a quick pre-emptive strike at Canada before the British Empire could

sieze the Panama Canal and the Philippines. What the actual Imperial General Staff contingency

plans were probably remain

buried in some long forgotten vault beneath Whitehall.

Acts providing for the Pacific Railroad were passed by the Northern Congress in 1862 and 1864.

The 1864 Act provided for grants of land, mineral rights, and government loans. The loans were

of varying amounts per mile, based on terrain, $16,000 per mile to a point west of

present day Cheyenne, $48,000 for the next 150 miles and $32,000 per mile thereafter.

Tracklaying, 1868

As indicated by the above images, across the plains, the mountains, and the

Great American Desert, as Wyoming was then known, the railroad progressed using hand labor.

Two to Five Hundred miles ahead of the railhead came the surveyors, followed by tunnelers and bridgers.

Behind them, still a hundred miles before the railhead came the grading crews, leveling the grade with

shovel and pickax. And behind the grading crews were the tie-layers, installing between 2,260 to 2,640 ties per mile. But

even ahead of them, in the Medicine Bow were tie hacks, cutting trees and shaping them by

hand, floating them down rivers and streams to the right-of-way for use by the tie-layers. And before

the railroad crews even arrived, miners commenced coal mines in Carbon and near Rock Springs to provide

fuel for the locomotives.

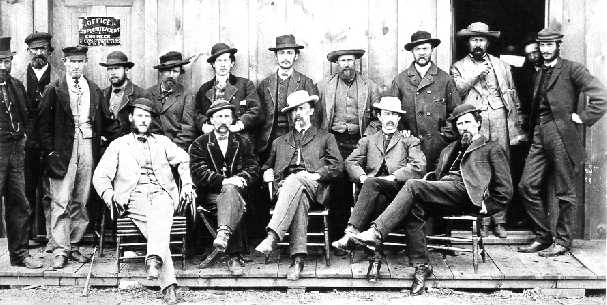

Office of the Superintendent of Construction, Laramie City, 1867

Behind the tie-layers came the "rust eaters" installing the rails. Trains brought supplies from

Omaha, 500 miles to the east. From the supply trains, rails were placed on horse-drawn cars, 16 rails per car, and at

a full gallop the car was taken to the end of track. Four men to a rail, each rail was lugged into place. Rails were

aligned with a wooden guage and upon command of the foreman, three men levered

each rail into place. And behind those men, others drove the spikes, two spikes per

rail, per tie, over 9,000 spikes per mile. Rails were connected, one to the other with

"fish plates," four bolts per rail.

In addition to the actual construction of the railroad, other

infastructure needed to be built. Machine shops, roundhouses, watertanks, hotels, and eating houses all had to be constructed before

the railroad could carry passengers.

Early view of Railroad Yards, Laramie |

Checker game in UPRR Paymaster's Tent, Laramie, 1868, A. J. Russell |

Similar windmills to that depicted above were located at other stations including Cheyenne and Sherman. The windmills had a diameter of

20 feet. The tank would hold 50,000 gallons and would take approximately 10

hours to fill. The tank was equipped with a float connected to the windmill by cable which,

when the tank was full, would automatically shut down the vanes. Another

float would automatically start the windmill when the tank neared empty. In the

background is a twenty-stall roundhouse and the machine shop.

Music this Page,

"I've been working on the Railroad"

(Courtesy Horse Creek Cowboy)

I've been working on the railroad

All the live-long day.

I've been working on the railroad

Just to pass the time away.

Don't you hear the whistle blowing,

Rise up so early in the morn;

Don't you hear the captain shouting,

"Dinah, blow your horn!"

Dinah, won't you blow,

Dinah, won't you blow,

Dinah, won't you blow your horn?

Dinah, won't you blow,

Dinah, won't you blow,

Dinah, won't you blow your horn?

Someone's in the kitchen with Dinah

Someone's in the kitchen I know

Someone's in the kitchen with Dinah

Strummin' on the old banjo!

Next page, The Building of the Union Pacific continued.

|