|

Army Train crossing the plains.

The Mormon War, sometime known as the "Utah War" or "Buchanan's Blunder," arose out of the loss of the postal

contract by Brigham Young's express company and President Buchanan's concern that Brigham Young was intent on making

Deseret, as Utah was then known, an independent state. Notwithstanding warnings from former Texas President Sam Houston that if

a military force were sent to Salt Lake City, all the Army would find would be a "heap of ashes," President Buchanan determined to

remove Young as territorial governor and replace him with a non-Mormon. Young, on the other hand,

determined that no hostile forces were to enter the territory, and, indeed, demanded that federal forces surrender

their arms and ammunitions. President Buchanan in an address to Congress noted:

A Territorial government was established for Utah by act of Congress

approved the 9th September, 1850, and the Constitution and laws of the

United States were thereby extended over it "so far as the same or any

provisions thereof may be applicable." This act provided for the

appointment by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the

Senate, of a governor (who was to be ex officio superintendent of Indian

affairs), a secretary, three judges of the supreme court, a marshal, and

a district attorney. Subsequent acts provided for the appointment of

the officers necessary to extend our land and our Indian system over the

Territory. Brigham Young was appointed the first governor on the 20th

September, 1850, and has held the office ever since. Whilst Governor

Young has been both governor and superintendent of Indian affairs

throughout this period, he has been at the same time the head of the

church called the Latter-day Saints, and professes to govern its members

and dispose of their property by direct inspiration and authority from the

Almighty. His power has been, therefore, absolute over both church and

state.

Brigham Young

The people of Utah almost exclusively belong to this church, and believing

with a fanatical spirit that he is governor of the Territory by divine

appointment, they obey his commands as if these were direct revelations

from Heaven. If, therefore, he chooses that his government shall come in of

collision with the Government of the United States, the members of the

Mormon Church will yield implicit obedience to his will. Unfortunately,

existing facts leave but little doubt that such is his determination.

Without entering upon a minute history of occurrences, it is sufficient to

say that all the officers of the United States, judicial and executive,

with the single exception of two Indian agents, have found it necessary

for their own personal safety to withdraw from the Territory, and there no

longer remains any government in Utah but the despotism of Brigham Young.

This being the condition of affairs in the Territory, I could not mistake

the path of duty. As Chief Executive Magistrate I was bound to restore the

supremacy of the Constitution and laws within its limits. In order to effect this purpose, I appointed a new governor and other Federal officers for Utah and sent with them a military force for their protection and to aid as a posse comitatuts in case of need in the execution of the laws. With the religious opinions of the Mormons, as long as they remained mere opinions, however deplorable in themselves and revolting to the moral and religious sentiments of all Christendom, I had no right to interfere. Actions alone, when in violation of the Constitution and laws of the- United States, become the legitimate subjects for the jurisdiction of the civil magistrate. My instructions to Governor Cumining have therefore been framed in strict accordance with these principles. At their date a hope was indulged that no necessity might exist for employing the military in restoring and maintaining the authority of the law, but this hope has now vanished. Governor Young has by proclamation declared his determination to maintain his power by force, and has already committed acts of hostility

against the United States. Unless he should retrace his steps the Territory

of Utah will be in a state of open rebellion. He has committed these acts

of disloyalty notwithstanding Major Van Vliet, an officer of the Army, sent to

Utah by the Commanding General to purchase provisions for the troops, had

given him the strongest assurances of the peaceful intentions of the

Government, and that the troops would only be employed as a posse comitatus

when called on by the civil authority,- to aid in the execution of the laws.

There is reason to believe that Governor Young has long contemplated this

result. He knows that the continuance of his despotic power depends upon the

exclusion of all settlers from the Territory except those who will

acknowledge his divine mission and implicitly obey his will, and that an

enlightened public opinion there would soon prostrate institutions at war

with the laws both of God and man. He has therefore for several years,

in order to maintain his independence, been industriously employed in

collecting and fabricating arms and munitions of war and in disciplining

the Mormons for military service. As superintendent of Indian affairs he

has had an opportunity of tampering with the Indian tribes and exciting

their hostile feelings against the United States. This, according to our

information, he has accomplished in regard to some of these tribes, while

others have remained true to their allegiance and have communicated his

intrigues to our Indian agents. He has laid in a store of provisions for

three years, which in case of necessity, as he informed Major Van Vliet,

he will conceal, "and then take to the mountains and bid defiance to all

the powers of the Government."

Army Train and Cattle Crossing the Plains. Harper's 1858

Planning for an expedition to

Utah commenced at Ft. Leavenworth in the Spring of 1857. Gen. Scott's ordered provided that

2,000 head of cattle were to be driven alongside the column. In July, Mormon spies reported to

Young that forces consisting of over 400 wagons, 6000 mules and oxen, and 1000 horses were on the march

westward. In August, Young declared martial law. [Writer's note: Church tradition gives the date that Young learned of the

pending invasion as July 24. There are some indications that Young knew as early as

June 26. July 24, however, has great significance as it marked the tenth anniversary of the founding of Salt Lake City, a

date now celebrated as Pioneer Day.]

The expedition, guided by Jim Bridger, actually consisted of 2,500 men and made slow progress. During the first three days it averaged about 16 miles a

day and it took a month to go 415 miles. Progress was slowed by the poor condition of the men, blamed on

"habits of dissipation" and the Army's bean soup. Within a month scurvy appeared. Although the cause of

scurvy had been known since the time of the Napoleonic Wars, some Army surgeons still believed that it

was caused by poor ventilation, lack of exercise, boredom, and the "filthy narcotic, tobacco." On the Platte, some of the

troopers were unable to resist the charms of Pawnee women and came down, as a result, with

social ailments.

In the meantime, Brigham Young directed that the Army be slowed down by guerilla action and defensive measures to be taken in

Echo Canyon. Army supply trains were burned by the Mormons. Working as a bullwhacker on one of the burned wagon trains was a

12-year old boy later to achieve fame as "Buffalo Bill," William F. Cody. On the route followed by the Army, the Mormons followed a literal scorched earth policy of burning all forage, indeed, burning all

the ground for a distance of seven miles from Fort Bridger. In Echo Canyon the Mormons piled rocks so that rock slides could block the Canyon. Dams were constructed in which

barrels of gunpowder were placed so that floods could be discharged upon any invading troops. Just how effecive the measures were is

open to speculation. Horace Greeley in his 1860 account of his passage to San Francisco noted of

the fortifications:

We stopped to feed and dine at the site of "General"

Well's Camp during the Mormon War of 1857-8, and

passed, ten miles below, the fortifications constructed

under his orders in that famous campaign. They seem

childish affairs, more suited to the genius of Chinese

than of civilized warfare. I cannot believe that they

would have stopped the Federal troops, if even tolerably

led, for more than an hour.

Daniel H. Wells, was designated by Brigham Young as "Lieutenant General" and commander of the Nauvoo Legion in which all

able-bodied men between 18 and 45 were enrolled. The purpose of the Mormon actions was to require

that Johnston's forces would have to winter over in Wyoming. So that the Army would not have

a place of shelter, Forts Supply and Bridger were burned down.

A New York Times correspondent described the scene at Fort Bridger when the Army arrived:

We reached Fort Bridger on the 14th [of November, 1857], and we shall remain here, in camp, this Winter. The wall

of the Fort is built of cobble-stone, laid in mortar, four feet thick at the bottom about two

feet thick at the top, and twenty feet in height. Adjoining this wall is a large corral,

inclosed by a stone wall of the same description, about eight feet in height. These

improvements were found uninjured, but the wooden gates, (which were very strong,

(were almost entirely consumed by fire; all the buildings which surrounded the Fort were

also burned to the ground. Hearing that there were vegetables at Fort Supply, cached and

yet in the ground, a party went there to-day to see what could be found.

Ruins of Ft. Bridger, 1858. Foundations of the fort are in the left and center foreground.

The New York Times correspondent contines:

On arriving at the spot I realized for the first time in my life what I had imagined of the

appearance of a sacked, burned and abandoned village. The place was marked by the blackened

and charred timbers sticking up in every direction, and by the tumbling adobe walls and mud

chimneys. There was a sense of desolation about those ruins of a recently beautiful settlement

which was, to say the least, unpleasant. The Fort had been surrounded by pickets, which had

burned down with the buildings. This settlement contained about 18 houses besides a grist and

saw mill. There were about 40 acres of potatoes in the ground, but they were all spoiled by

the frost. We found, by poking about among the ruins, a hole containing about three bushels of

excellent potatoes. We found a patch of turnips and beets uninjured by the frost, and of them

we secured a good supply. The wheat had been cut before the Mormons left, and had been burned

in the stack. In the meadow there was 5 acres of hay, cut and lying as it had been raked up at

the time of cutting.

Just before leaving the place a black and white cat ran out towards us, from under a pile of

half-burnt timber. We gave her food and tried to capture her. She would not allow that, but

persisted in keeping her lonely watch over the ruins of the old home.

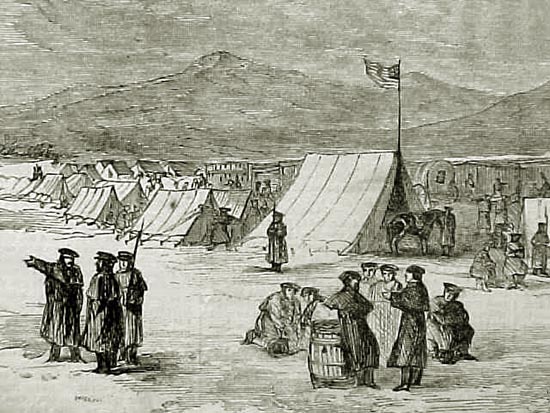

A part of the camp at Fort Bridger, Harpers Weekly, January, 1858.

The above scene is somewhat inaccuarate. The Fort in the right background had been burned down by

William A. Hickman in the autumn as a part of the Mormon's scorched earth defense. The tents are also

inaccurate. The Army used 250 of Henry Sibley's newly invented and patented conical tents rather than the

walled tents depicted in the image. The tents in the next image from Leslies is more accurate.

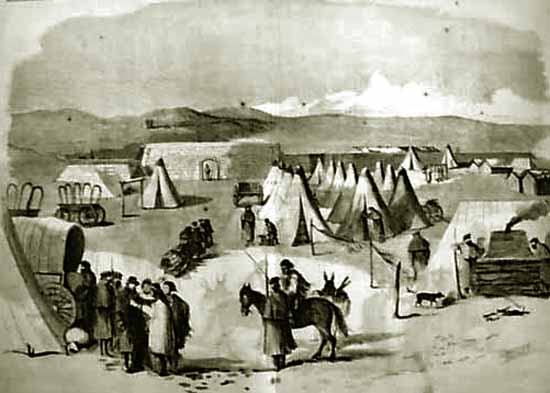

A part of the camp at Fort Bridger showing Sibley tents, Leslie's News., 1858.

The army agreed to pay Major Sibley $5.00 for each tent used by it.

Sibley prior to the Civil War assigned one-half of the rights to a fellow officer W. W. Burns. At the beginnng of the

Civil War, Major Sibley enlisted in Confederate forces. Burns remained in Union forces. The army cut off payments to both

Sibley and Burns, arguing that Burns needed to look to Sibley for his half. Ultimately after the

Civil War the Courts held that Sibley's patent was good, but he was entitled to nothing. Burns, however,

was entitled to his half of the $5.00.00.

Inside an Officers' Tent, Harper's 1858.

As noted above,

Forts Supply and Bridger were burned down so that the Army would not have a place of shelter. The winter, in fact, was more severe than normal and

Johnston's troops wintered over at Ham's Fork. Scurvy lessened with the use of

dried fruits and native plants such as wild onions. Nevertheless, the Army faced a new and strange disease with which the

surgeons were unfamiliar, referred to by the Mormons as "mountain fever," now believed to be

Colorado tick fever. The Army remained inspired, however, by the belief that they would soon be welcomed

by the arms of grateful women being freed from the "harems" in Utah. Certainly, an anti-Mormon attitude was not

limited to the rank and file. One Army surgeon, Dr. Roberts Bartholow (1831-1904), noted in an

official report that Mormons had:

an expression compounded of sensuality, cunning, suspicion, and a smirking

self-conceit. The yellow, sunken, cadaverous visage; the greenish-colored

eyes; the thick protuberant lips; the low forehead; the light, yellowish

hair; the lank, angular person, constitute an appearance so characteristic

of the new race, the production of polygamy, as to distinguish them a glance.

Albert Sidney Johnston

Not all military officers thought ill of the Mormons. Capt. Stansbury in his report noted:

In what has been said respecting the Mormon community, I have endeavoured

frankly to present the impression produced upon my mind by a somehat intimate acquaintance of a

year's duration with both rulers and people. The intelligence of their

organization into a Territorial Government, had not reached the valley when we

left it. How far the change in their relations to the country, may, as has been

asserted, have revolutionized the feelings of the people, it is impossible for me to

say. But not representations, that have yet been made public, have

served in the least to alter my expressed opinion of their character for either love to the country,

or layalty to the government. Since the return of the expedition, it has appeared evident that

the nature of the domestic relations of the Mormons has been very generally misapprehended.

It seems that the "spirtual wife system," as it has been very improperly

denominated has been supposed to be nothing more nor less that the

unbridled license of indiscriminate intercourse between the sexes, either openly practised by all, or

indulged, to the invasion of individual rights, by the spiritual leaders. Nothing

can be further from the real state of the case. The tie that binds a

Mormon to his second, third, or fourth wife, is just as strong, sacred, and indissoluble, as that which unites him to his

first. Although this assumption of new marriage bonds be called "Sealing," it is contracted,

not secretly, but under the solemn sanctions of a religious ceremony, in the

presence, and with the approbation and consent of relatives and friends. Whatever

may be thought of the morality of this practice, none can fail to perceive that it

exhibits a state of things entirely different from the gross licentiousness which is generally thought to

prevail in this community, and which were it the case, would justly commend itself to the

unmingled abhorrence of the whole civilized world. The recent acquittal of a

Mormon Elder for shooting the seducer of one of his wives, on the ground that the act was

one of justificable homicide, fully corroborates the truth of this remark,

and shows in how strong a light the sacredness and exclusive character of such relations

are viewed by the Mormons themselves.

Anson Mills was stationed at Fort Bridger following the Civil War. In his autobiography he wrote:

I was prejudiced against the Mormons, but found they were the best people in the country,

and the only ones who would fill contracts fairly. The Gentiles practiced every device to

beat the government, but the word of a Mormon was his bond. With Major Lewis commanding Fort

Douglas at Salt Lake, I called upon Brigham Young. He looked like General Grant, and was

an earnest and, I believe, a sincere and conscientious man. He said he was glad to meet a regular officer, because the regular army always treated them well, but that the volunteers under Connor had been demoralizing to those of the Mormon faith. Discussing my prejudice against his people, about which he asked and I answered frankly, he said, "You have doubtless heard we are disloyal to the Union." Pointing to the flag flying over his Tabernacle, he said it had waved every day since the war began. Upon his invitation I attended his church and heard him preach the next Sunday. I visited the Tabernacle in company with his son-in-law and saw open on the pulpit the inspired volumes from which they preached —the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon. He presented a copy of the latter to me, inscribed with his name, which I still have. My experiences changed my mind regarding the Mormon people. I believe their church the equal of any in the inculcation of those qualities which make the Mormons law-abiding, industrious, economical and faithful to all their agreements.

Ultimately, In the spring it became apparent that the Mormons would be unable to

resist the federal force. Thus, without the necessity of an armed invasion,

a compromise was reached and the war ended. The Mormons permitted the new non-L.D.S. governor to be seated. The

Territory provided an appropriate place of residence for the new governor in the

most comfortable quarters in the City, the residence of Elder William C. Staines.

President Buchanan issued a "Proclamation of Pardon." Yet, military occupation was required. In 1862,

troops were quartered nearby in a fort in which the cannons were aimed at Church President Young's

personal residence. Strong differences of opinion exist as to the results of the war.

Some contend that it was a Mormon victory; that no one was killed in action [a claim subject to

some doubt in light of the allegations of William A. Hickman and the murder of the 120 members of the

Francher Party at Mountain Meadows, claims vigorously denied by Brigham Young]; and Brigham Young was not

hanged as perhaps Albert Sidney Johnston may have desired. Mormons may have had, in light of the

fate of the Church's founder, a justified fear that the purpose of the

expedition was other than to remove Young. Certainly, there was a hew and cry in

the east about the alleged licentiousness of Church leaders, a view perhaps echoed in the

Wyoming Constitution providing that Freedom of Religion "shall not be so

construed as to excuse acts of licentiousness or justify practices inconsistent with the peace or safety of the state."

Next page: Fort Bridger continued.

|