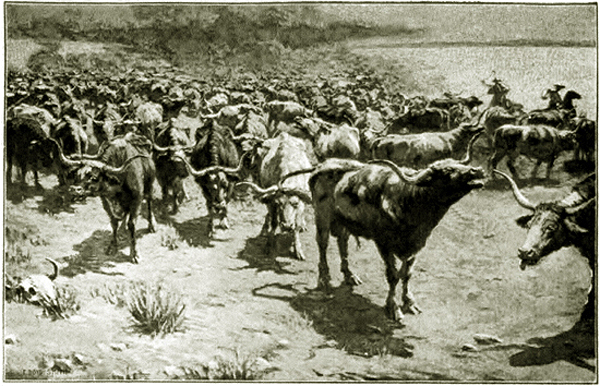

Trail Herd heading north, G. B. Dobson based on engraving by

Jean Andre Castaigne.

The practice of trailing cattle goes into great antiquity. See Book 2, Exodus:

Our cattle also shall go with us; there shall not an hoof be

left behind; for thereof must we take to serve the LORD our

God; and we know not with what we must serve the LORD, until

we come thither.

Outlaw and former cowboy Polk Wells noted that:

[S]acred history shows that Abel "brought of the firstlings of his flock and offering unto the Lord." Abraham and

Lot had herds in the land of Canann, "and there was a strife" between thir cow-boys. Saul was a

ranchman and Da, an Edomite, was his foreman, and kept on hand an army of cowboys. Amos was a cowboy in Syria, and Moses himself

participated in the great "round-up" in Egypt. And Isaac was a cattle king in

Gerar. St. Patrick, the exterminator of snakes herded cattle on the mountains of Ireland * * *.

Wells, p. 155.

Trail Herd, engraving, E. Boyd Smith.

Ranching in Wyoming started in the 1850's but received its real impetus as a result of the end of the Civil

War and the coming of the railroad. Cattle valued at $5.00 a head in Texas would bring ten fold that amount at

a railhead. Thus, there began the cattle drives to railheads in Kansas and to

Cheyenne. As explained by Andy Adams (1859-1935) in the Preface to his 1895 work, The Outlet:

At the close of the civil war the need for a market for the

surplus cattle of Texas was as urgent as it was general. There

had been numerous experiments in seeking an outlet, and there is

authority for the statement that in 1857 Texas cattle were driven

to Illinois. Eleven years later forty thousand head were sent to

the mouth of Red River in Louisiana, shipped by boat to Cairo,

Illinois, and thence inland by rail. Fever resulted, and the

experiment was never repeated. To the west of Texas stretched a

forbidding desert, while on the other hand, nearly every drive to

Louisiana resulted in financial disaster to the drover. The

republic of Mexico, on the south, afforded no relief, as it was

likewise overrun with a surplus of its own breeding. Immediately

before and just after the war, a slight trade had sprung up in

cattle between eastern points on Red River and Baxter Springs, in

the southeast corner of Kansas. The route was perfectly feasible,

being short and entirely within the reservations of the Choctaws

and Cherokees, civilized Indians. This was the only route to the

north; for farther to the westward was the home of the buffalo

and the unconquered, nomadic tribes. A writer on that day, Mr.

Emerson Hough, an acceptable authority, says: "The civil war

stopped almost all plans to market the range cattle, and the

close of that war found the vast grazing lands of Texas fairly

covered with millions of cattle which had no actual or

determinate value. They were sorted and branded and herded after

a fashion, but neither they nor their increase could be converted

into anything but more cattle. The demand for a market became

imperative."

Cattle Trail, Harper's Weekly, 1867

This was the situation at the close of the '50's and meanwhile

there had been no cessation in trying to find an outlet for the

constantly increasing herds. Civilization was sweeping westward

by leaps and bounds, and during the latter part of the '60's and

early '70's, a market for a very small percentage of the surplus

was established at Abilene, Ellsworth, and Wichita, being

confined almost exclusively to the state of Kansas. But this

outlet, slight as it was, developed the fact that the

transplanted Texas steer, after a winter in the north, took on

flesh like a native, and by being double-wintered became a

marketable beef. It should be understood in this connection that

Texas, owing to climatic conditions, did not mature an animal

into marketable form, ready for the butcher's block. Yet it was

an exceptional country for breeding, the percentage of increase

in good years reaching the phenomenal figures of ninety-five

calves to the hundred cows. At this time all eyes were turned to

the new Northwest, which was then looked upon as the country that

would at last afford the proper market. Railroads were pushing

into the domain of the buffalo and Indian; the rush of emigration

was westward, and the Texan was clamoring for an outlet for his

cattle. It was written in the stars that the Indian and buffalo

would have to stand aside.

Portion of Trail Herd to Wyoming, Oil on canvas,

W. H. D. Koerner, 1923

Philanthropists may deplore the destruction of the American

bison, yet it was inevitable. Possibly it is not commonly known

that the general government had under consideration the sending

of its own troops to destroy the buffalo. Yet it is a fact, for

the army in the West fully realized the futility of subjugating

the Indians while they could draw subsistence from the bison. The

well-mounted aborigines hung on the flanks of the great buffalo

herds, migrating with them, spurning all treaty obligations, and

when opportunity offered murdering the advance guard of

civilization with the fiendish atrocity of carnivorous animals.

But while the government hesitated, the hide-hunters and the

railroads solved the problem, and the Indian's base of supplies

was destroyed.

Then began the great exodus of Texas cattle. The red men were

easily confined on reservations, and the vacated country in the

Northwest became cattle ranges. The government was in the market

for large quantities of beef with which to feed its army and

Indian wards. The maximum year's drive was reached in 1884, when

nearly eight hundred thousand cattle, in something over three

hundred herds, bound for the new Northwest, crossed Red River,

the northern boundary of Texas. Some slight idea of this exodus

can be gained when one considers that in the above year about

four thousand men and over thirty thousand horses were required

on the trail, while the value of the drive ran into millions. The

history of the world can show no pastoral movement in comparison.

The Northwest had furnished the market--the outlet for Texas.

Andy Adams worked as a cowboy for ten years in Texas, including eight years on

the trail prior to 1890. Subsequently, he became a writer of western fiction.

Although fiction, his works embody his experiences on the trail and are regarded today

as providing an accurate depiction of life on the trail.

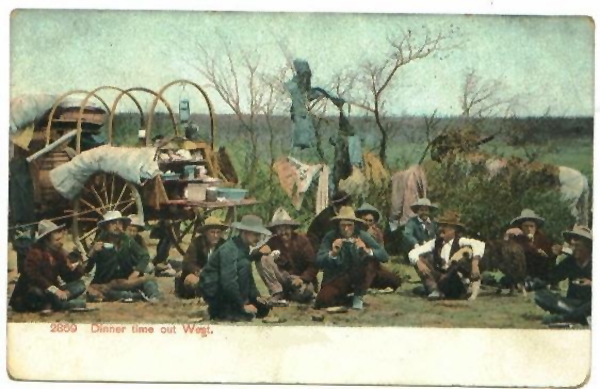

Trail Camp, undated. Site believed to be

near Cash Creek, Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma).

But the first of the great drives was not to a railhead in Kansas, but was the epic drive by Nelson Story (1838-1926) to Montana. Story, a former

freighter on the Great Plains, made a fortune mining for gold in Montana. He realized that in the

mining camps, there was a pent up demand for beef. Thus, in 1866, he proceeded to Texas and purchased over a 1,000 head of

longhorns. With some 27 drovers and bullwhackers he proceeded northward. In Kansas, the drive was forced

westward by Jayhawkers. At Fort Laramie, Story resisted the Army's efforts to buy the stock on the cheap.

Instead, buying additionally arms from the fort sutler, Story continued along the "Bloody Bozeman."

Near Fort Reno, the herd was attacked by Sioux who stole a portion of the herd and stampeded the

rest. After recovery of the stampeded cattle, Story and his men then went after the stolen herd. Story later

recalled that it was the first time he ever killed an Indian. But by the end of the night, no

Indians were left to complain. At Fort Phil Kearny, because of the Indian peril, the

Army refused to allow the herd to continue, but at the same time insisted that the cow camp be

established away from the fort's protection some three miles distant. It

should not, therefore, have been a surprise for Col. Carrington to awaken

one morning to find that

Story, his men, and cattle had decamped during the dark of the night. Thus, was established the cattle industry in

Montana.

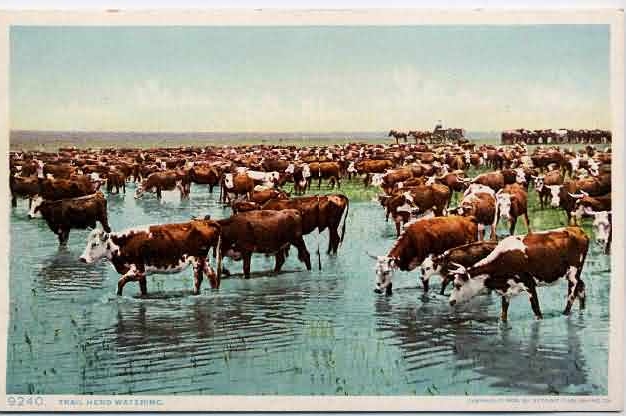

Trail Herd Watering, photochrom by Detroit

Publishing Co., 1905.

For discussion of the Detroit Publishing Company and its "photochrom" process, see

Yellowstone. Many of the Detroit Publishing photographs are

attributed to its manager, William Henry Jackson. Whether the photos were

actually taken by him is questionable. Note the remuda in the right background. For

discussion of remuda see Cattle III.

Although the cattle drives of the early 1870's were to railheads in Kansas, with the solution to the Indian problem

in 1877, Northern Wyoming and Eastern and Central Montana were opened to stock growing. It was discovered

that cattle fattened quickly on the grasslands of the Northern Plains. Thus, cattle were driven north from Texas to Wyoming and

Montana. In 1883, it was estimated that 260,000 head were driven north.

A typical herd consisted of about 2,000 head with a trail

boss and a dozen men, although some herds of up to 15,000 were driven north with much bigger crews. Life on the trail was hard. Edward "Teddy Blue" Abbott,

We Pointed Them North: Recollections of a Cowpuncher (Farrar & Rinehart, 1939; University of Oklahoma Press, 1955) observed:

"They had very little grub and they usually run out of that and lived on straight beef, they had only three or four

horses to the man, mostly wth sore backs, . . .they had no tents, no tarps, and damn few slickers.

They never kicked, because those boys was raised under just the same conditions as there was

on the trail--corn meal and bacon for grub, dirt floors in the houses, and

no luxuries."

Actually, it was rare to get "straight beef" on the trail, particularly on drives

conducted by "contract drovers" who were driving cattle owned by someone else. On the trail

there was no way of preserving beef and, thus, the menu was limited to items which

would keep, i. e. beans, biscuits and coffee, or the occasional "slow elk," a cow belonging to

another outfit. In the latter instance everything was used, giving rise to a

trail delicacy, "S.O.B. stew," made of tallow, tongue, liver, sweet breads, brains, marrow gut, and

anything else except hoofs, horn and hide.

Dinner Time on Roundup, Detroit Publishing Co., 1905

The above scene is more likely on a roundup rather than on a trail drive. On the

trail it would have been rare for the cook to have time to put up the canopy.

The nature of the food was noted by James Peake Royston, a cowboy who rode on

a cattle drive for the Searight Cattle Company from Oregon, discussed below:

"When those cattle reached Boise City, Idaho, our mess wagon had to take on

a fresh supply of grub. The order was nine sacks of kidney

beans - eleven hundred and twenty five pounds - a thousand pounds

of sugar, coffee and dried fruits in proportion. It just occurred

to me that if these one hundred punchers, horse wranglers, night hawks,

silk tie foremen got their proportional part of those beans and sugar

there would be some sweet beans on the trail to Wyoming."

"Slow elk" were not always eaten. A bonus might be given for strays. William Owens,

who started as a cowboy in 1875 when he was orphaned at age 12, described a drive from

Texas to Montana:

"The first and only real drive I made was with Turk Beall. We drove the herd

from Texas to the section where Butte. Mont. is now located. We started out

with 1,200 head and had the usual sorefoot trouble with critters that had

to be dropped, had occasional stampedes that caused more or less loss, but

with the usual precentage of losses deducted, we still arrived with a herd

of 2,400 critters.

"Our orders were to pick up two strays for every one we lost in a stampede

and put the iron on the animals. We traveled through cattle country, more

or less, the whole distance and strays kept getting into our herd.

Us waddies were paid $1. as a bonus for each critter that we hold which

strayed into the herd.

"When the weather was pretty an everything going fair, so that a couple

waddies could take a little run off to look over the surrounding country,

we would do so. While looking over the country, if by chance, we run onto

good looking critters, which appeared lonesome and looking for company, we

would give these critters an invitation to join our herd and show the

animals which way to go.

"There was a bunch of 14 waddies on the drive and when the settlement was

made at the finish of the trip we divided $1,500 of bonus money.

[Writer's note: "Waddie" originally referred to a rustler. Later it meant a cowboy who

drifted from outfit to outfit. A bonus of $1,500 meant that some 1,500 strays were picked

up on the drive. Thus, Owens' math of starting out with 1,200 and arriving in Montana

with 2,400 head is fairly accurate. Such depredations are regarded by many as

a cause of the Johnson County War.]

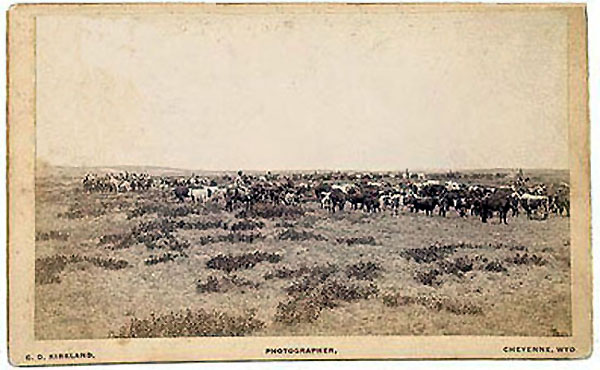

Wyoming Trail Herd, 1880's. Photo by C. D. Kirkland

Another cowboy, John J. Baker, also noted the practice of picking up strays along the

drive. He commented that on a drive to Montana the contract drovers

"paid their waddies a bonus of 50 cents for each maverick found and branded. The 50

cent bonus caused many a good waddie to have eye trouble and they could not see the

brand on the critters that the mavericks were running with or know the range they were on."

Attitudes toward picking up stays depended upon one's perspective.

Early Texas trail driver, M. J. Ripps, recalled:

Now, in gathering these cattle on different ranches we came across cattle that had strayed from

other ranches, and their owner not being present, we would send him word that we had one steer,

a cow, or a number of his cattle, as the case may have been, and paid him the prevailing price.

This was within the law and in use quite generally. Cattle that had no brand or markó well,

that was not our fault. But it is remarkable the way these cattle persisted in following the

herd. Naturally, our sympathy was with them.

On the other hand, if one was a rancher in Kansas near which the Texas herds passed on the way

northward, such as C. S. Brobent who was a stockman near Caldwell, it was dishonest:

There was some dishonesty in this trail driving. A trail boss who did not reach his destination with an equal or greater number

than he started with was considered incompetent. Hence ranchers along the trail made

bitter complaints of moving herders "incorporating" their stock.

Andy Adams described on incident where the boredom with the food was relieved.

After crossing the Niobrara, the crews from several wagons stopped to pick raspberries.

the cook from one wagon baked in a dutch oven individual pies for all of

the men.

Making Pies on the Mess Wagon. Photo by C. D. Kirkland

The food at the home ranch might, however, be better. Louis Newman who signed on with

the Flying Circle Ranch on Thunder Creek as a wrangler at age 14 described the food:

Bob Burns came to the ranch from the East, where he had learned the trade and he had cooked in a number of

the leading Eastern hotels. Therefore, our food was well cooked and we

had a good varity of everything but the meat. Beef was our main meat

food with some bacon occasionally. However, the beef was from prime

yearlings and Burns cooked it in many different forms, so we didn't become

tired of the meat. Our vegetables were the canned goods. The bread

and pastery were made by the cooks and those items were well made.

In fact, out meals were equal to those served by the general run of

first class hotels.

Day Herding on the Trail

Next Page: Cattle Trails continued, Ogallala, Powder River Let 'er Buck.

|