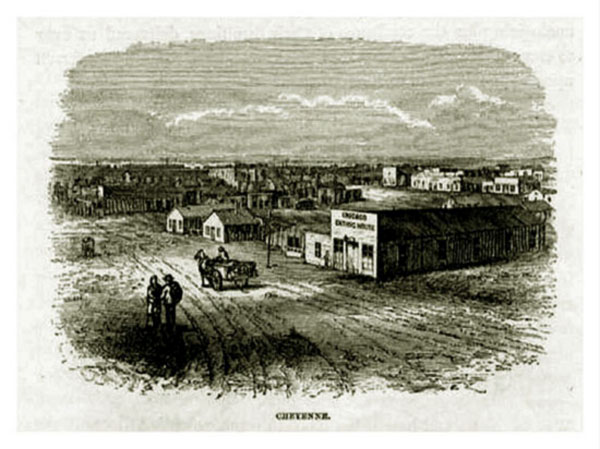

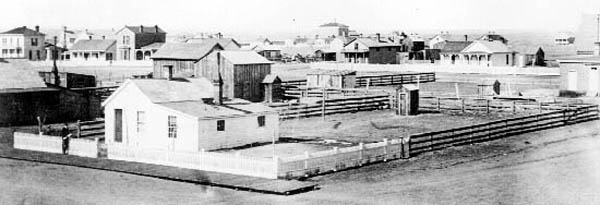

Cheyenne, 1867, looking toward 16th Street at top of hill.

Cheyenne was laid out by

Gen. Dodge as a division point before the Railroad began its climb westward over the

Gang Plank and the summit at Sherman Station. And like many end of tracks towns, it was

an overnight wonder, a tent city in which the residents would do business and move on the

the next end of tracks city. Such was the town's first mayor, H. M. Hook, an owner of the

Great Western Corral on the corner of O'Neal and 20th Streets. Hook had come from

LaPorte, Colorado, a stage station soon bypassed as a result of the railroad. Previously,

Hook had been the stage station manager at Dogtown, Nebraska, an adobe establishment, nine miles east

of Fort Kearney. Shortly after his installation as mayor, Hook again moved westward to Green River

City. Green River, itself, almost faded from existence when Bryan was made the division point. Allegedly,

Hook drowned while attempting to navigate the Green River on a raft on a prospecting

expedition.

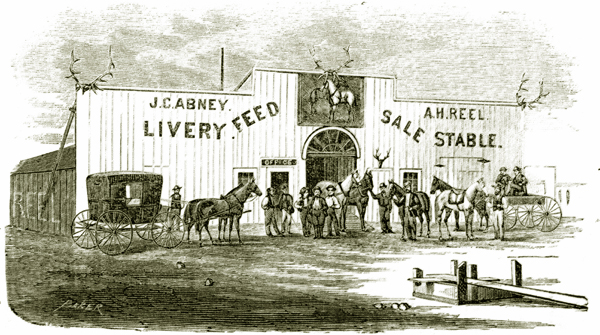

James C. Abney and Alexander H. Reel's Elkhorn Livery Barn, corner of

18th and Reed, Cheyenne, 1868

The above depicted livery barn later burned and was replaced by a brick livery depicted on a later page. James Clay "J. C." Abney (1837-1899) with Alexander "Heck" Reel (1837-1900)

both moved to Denver from

Nebraska City and established a livery stable in Denver. With the coming of the railroad to Cheyenne, they moved the

livery operation to Cheyenne. Abney had been on his own from about the age of 12 and had been a range rider. Reel, had been a freighter, running frreight from

Nebraska City to Salt Lake City by way of Denver. Abney was elected to the first territorial legilature and was the

first legislator to speak and vote for women's sufferage. Reel later served in the legislature both in the House and the Senate. He also served as

major of Cheyenne. Reel's sister, also as later discussed was the first woman in the United States elected to a state-wide office. In Cheyenne, Reel ran freight for

the Army to Fort Fetterman. He later purchased the Spur Ranch in Lincoln County where he died in 1900. Abney had several postal contracts with the United States. During the

last two years of his life, he served as a Justice of the Peace.

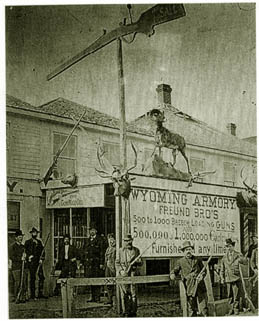

Others who followed the tracks westward from Nebraska City to Cheyenne included gunsmiths Franz Wilhelm "Frank" Freund (1837-1910)

and his brother George Freund who came in 1867 after short

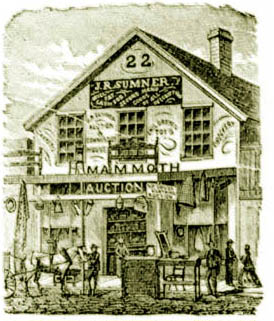

sojourns in end of the tracks towns North Platte and Julesburg. Auctioneer Jonathan R. "J. R." Sumner arrived the same year from

Colorado. The Freund Brothers established their gunsmithery in the Whitehead Building on Eddy Street. The Whitehead building was the first

permanent building constructed in Cheyenne. On the same street, Sumner established his

commission and auction business.

. . . . . .

Left, Freund Bro.'s gunshop, Whitehead Building, Eddy Street, undated; Right, J. R. Sumner's

Commission and Auction House, Eddy Street, 1868

The Freund Brothers continued moving west opening temporary gunshops at "end of the tracks" towns including

Dale City, Laramie, Benton, Green River, Bear River City, South Pass City, Corrine and Salt Lake City. They also opened a

shop in Denver on Blake Street. The Laramie store had a little more permancy. The brothrs each held various patents for

improvements to Sharp's rifles and made a few of their own carbines, the "Wyoming Saddle Rifle." They, however, maintained a continuing presence in Cheyenne until the brothers split up in

1880 when George moved to the next "hot" spot, Durango, Colorado, where he died in 1911. In 1885, Frank moved to Jersey City where he died in 1910.

J. R. Sumner remained in Cheyenne for less than two years and then moved westward. By 1870 he was in the San Francisco Bay area. He later lived in

Oakland and Berkley. For a brief time in 1880 he was in Bodie.

Cheyenne, 1868

The first lots sold for $150.00 each. Within a month, lots were selling for $1,000.00 each and increasing

monthly during the first summer. The first settlers were J. R. Whitehead, A. C. Beckwith, Thomas E. McLeland, later a city councilman and

postmaster, and Robert M. Beers. As depicted at the top of the page, the first houses were either tents or houses constructed of

lumber brought in from Colorado. The first tent was put up by A. C. Beckwith and the first permanent structure was constructed by

Whitehead (photo of Freund Brothers "Wyoming Armory" above). The Whitehead Building was razed in 1927.

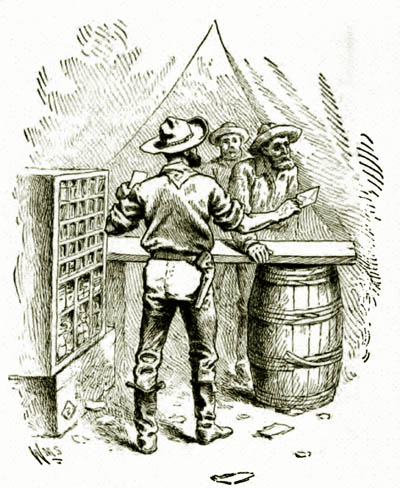

Interior Cheyenne Post Office, 1867 Interior Cheyenne Post Office, 1867

John W. Clampitt in his 1889 account Echoes From the Rocky Mountains described Cheyenne upon its founding:

As the day advanced we beheld in the far distance what appeared

to be a speck upon the horizon. As we approached, it assumed the

aspect of the white wings of motionless animals. They were the

white tents of the embryo city of Cheyenne—mere dots upon the vast

plain. They were the advance-guard of the army which shortly

appeared and laid the foundation of the capital city of the new Territory

of Wyoming. At that time there were not more than a dozen tents,

and yet the "new city" wore an aspect of business. Wells, Fargo &

Company had located upon a prominent corner, another tent covered

the United States post office, a third was a newspaper office, while the

others served as stores, saloons and places of commercial resort, not to

forget that of the justice of the peace, whose jurisdiction was boundless

amid the wilds of this Western civilization. He would hear and decide a

case in equity or on the law side of the court with as much composure

and firmness of purpose as if he was sitting and presiding as Chief

Justice of the Supreme Court of the Territory.

* * * *

The taste of those wedded to refinement in all things would have been

seriously shocked, by a glimpse at the internal arrangement of the Cheyenne

post office at that early day. I frequently visited it subsequently,

when it was sumptously furnished, when the town of phenomenal growth had attainted, within six months, a population

of 10,000, and the postmaster rejoiced in a salary of $3,000 per annum.

But at the period of which I speak, the office was a little wall tent and

the furniture a deal-box split in two, one half resting upon the upturned end of a second

box of like character, and partitioned off in pigeon holes of a rude

structure with the refuse lumber of the boken box.

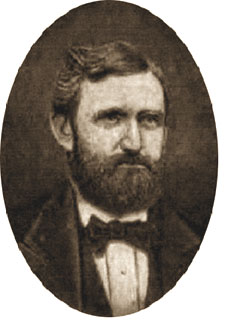

John Wesley Iliff John Wesley Iliff

With the arrival of the Union Pacific on November 13, 1867, Denver merchant, John Wesley Iliff,

received a contract from the Railroad to provide beef for the railroad crews. He

established a cow camp five miles down Crow Creek from Cheyenne. In town his place of business for wholesale and retail

sale of beef was on the south side of 17th Street. Thus, the town became a terminus of the Goodnight-Loving

Cattle Trail from Texas. Charles Goodnight drove cattle for Iliff up the Trail. The City literally, unlike Rome, was built in

a day. Thus, early promoters

portrayed the city as the "Miracle City of the Plains." None the less as a result of its end-of-the-trail status, it became known as the "Holy City of the Cow."

Crow Creek became a source of water for irrigation and the City's reservoirs. Thus, today as one

views the Creek in its full magnificence, one is reminded of the suggestion, attributed to Mark Twain as

to another mighty Western water course, that it should not be left out at night, lest a stray dog should

lap it all up. For more on Crow Creek and the City's reservoirs, see Silver Crown Mining District.

The Trail ran from northwest of San Antonio, crossed the

Pecos at Horsehead Crossing and then ran into New Mexico. From

there it followed the Pecos until the trail turned north into

Colorado passing near present day Deer Trail.

In the first year, Goodnight sold Iliff $40,000 worth of cattle and during

the period up to 1876 provided some 30,000 head of longhorn.

In 1867, the two partners trailed two herds of cattle from Texas to Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory.

The trail crossed the ninety mile wide waterless Llano Estacado, the staked plain, so-called because

early Spanish explorers had to stake their trail in order to find their way across. After reaching Horsehead Crossing,

Loving rode ahead with one of his drovers, Jim

Scott. Along the Pecos near present-day Loving, New Mexico, the two were attacked by Comanches. Loving's

mule was shot from beneath him. In the fall, one of Loving's legs was shattered. The two hid along the

bank of the river. Ultimately it became necessary for Jim to attempt to walk back for help. For two days and nights,

Jim made his way back toward the herd, He passed out with fatigue. He was found by his brother, a drover with Goodnight's herd.

In the meantime, Loving dispared of being found and attempted to crawl for help dragging his shattered leg. He passed out but was

found by a Mexican freighter on his way from Fort Sumner to Fort Stockton.

"Que vienen, hombres! Que vienen por el amor de Dios! Aqui esta un

muerto." But Loving was not dead.

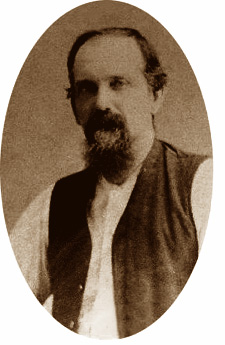

Charles Goodnight.

Shortly, Goodnight's and his men arrived. In a nine day's forced march,

Loving was carried in a crude Mexican wagon to Fort Sumner. Gangrene began to set in. But there was no

surgeon at the Fort. Loving's life could be saved only by amputation of the leg. The Fort hay and wood contractor, Scot Moore, rode the 130 miles through

Navajo infested territory to Las Vegas east of Sante Fe. Even today, U.S. Highway 84, which follows the route, is

a long, lonely deserted highway. A surgeon was obtained in Las Vegas and the two rode back to Fort Sumner. Moore covered 260 miles in

30 hours. But Loving was too weak and not withstanding the amputation died. His last wish was to be buried in

Texas. Goodnight dutifully carried his partner's body back 600 miles to

Texas from New Mexico in a buckboard. Because of the hot New Mexico sun, it was

necessary that the casket be filled with charcoal and sealed with flattened tins.

Goodnight is also noted for being the inventor of the chuckwagon.

In 1866 he bought a war surplus Studebaker army wagon, added a canvas cover, water barrel, tool box and nailed a

set of kitchen cabinets to the back. Studebakers were especially suitable since they

used steel axles and could take the rough ride over the trails. Eventually similar wagons were sold by

Studebaker Brothers for $75 to $100.

Historian, Dee Brown, has attributed the popularization of the term "cowboy"

to Goodnight's wife, Mollie, who referred to her husband's drovers as their "boys." The term, howver,

dates back to a least the American Revolution when it was used to describe Loyalist

rustlers in the Mid-Hudson Valley of New York. The most famous was Claudius

Smith who had a hideout in the Ramapo Mountains and would raid farms in Orange,

and Rockland Counties, New York and Bergen County, New Jersey. He was eventually captured and

hanged on January 22, 1779, at Goshen, New York. Rustlers who preyed on Loyalist farmers were known as "skinners."

Clay Allison, 1885

One of Goodnight's "boys" who helped lay out the Goodnight Trail was the

infamous self-styled "shootist" Robert Clay Allison. Allison after leaving Goodnight's employment, started

his own ranch in New Mexico in 1870. He could best be described as a belligerent drunk. The Confederate Surgeon

General's Department, in giving him an administrative discharge for medical reasons, described him as:

"incapable of performing the duties of a soldier because of a blow received

many years ago. Emotional or physical excitement produces

paroxysmals of a mixed character, partly epileptic and partly maniacal."

Allison reputedly killed 15 men. However, his reputation was initially made as a result of

his involvement in the lynching of Charles Kennedy. Kennedy, at the instigation of Allison, was

dragged out of a jail in New Mexico, taken to a local slaughter house and dispatched. He was

then decapitated by Allison, who impalled Kennedy's head on a pole, and carried it to Henry Lambert's

Saloon on the Cimarron for display. In another incident in Canadian, Texas,

Allison allegedly strode around town seeking a gunfight, clad only in boots, hat and

gunbelt with two revolvers. In Las Animas, Colo., Allison killed a deputy sheriff. Two other deputies

fled town. As a result of his reputation Allison found it increasingly difficult to

find a town where he was welcome to sell his cattle.

In 1886, Allison trailed a herd of cattle to Rock Creek. Suffering from a tooth ache, he

stopped off in Cheyenne on his return to New Mexico and sought out the services of a dentist. The dentist,

unfortunately, began drilling the wrong tooth. Allison left the dentist and had the

tooth corrected by another dentist. He then returned. Pinning the first dentist in his chair, Allison

commenced the forcible extraction of the dentist's teeth. Only the response of passersby to the screams

emitting from the dental office saved the dentist.

That, however, was not the only time that Allison visited Cheyenne. Allegedly, Allison was involved in a fight with

local residents of Dodge City. Shortly thereafter three men bushwhacked Allison outside of town. He survived by playing dead. He

recognized the three. When Allison recovered from his wounds and reappeared on the streets, the three deemed it

expedient to get out of Dodge. Allison was one not to forgive slights and proceeded over the next months

to track his assailants down. He found the first in Cheyenne. His assailant got off the first shot, but it

went wild. Allison's shot did not. The second assailant was found in Crook County along the

Belle Fourche and the third in Tombstone.

Cheyenne, 1876

Next page, Cheyenne Photos continued, Cheyenne 1868-69. |