|

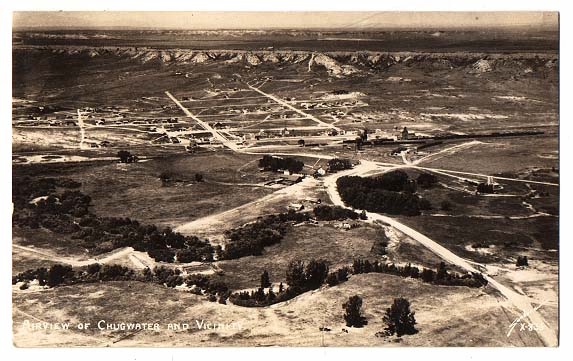

Chugwater, Wyo., 1930's

South of

Chugwater on Iron Mountain Road, a graded road periodically punctuated by cattle grates, is the ghost town of Diamond.

Further south near Iron Mountain was the Iron Mountain Ranch Company, owned by John Coble and

Henry C. Bosler. The ranch served as a "home away from home"

of Tom Horn when he was working as a "cattle detective." To the west lies

Bosler, a town which today barely survives.

Horn's cabin is still on the Iron Mountain Ranch near Bosler. Out of the eastern hills of Albany County a number of streams flow eastward.

Some such as Strong Creek, Ricker Creek, Shanton Creek, and Miller Creek were named after early settlers.

In the late 1870's and in the 1880's settlers came and established

modest homesteads and ranches along those streams. Further south is Horse Creek along which

others such as Harriman D. "Harry" Richardson also homesteaded. Such homesteads were, indeed, modest as

compared to the large spreads held by Swan's Two-Bar outfit, the Diamond Ranch, or that of Coble and Bosler.

Richardson Ranch, Horse Creek, Wyoming. Image Courtesy of

Keith Yeager.

Into this area, William E. "Bill" Lewis arrived about 1888 and acquired property between Chugwater Creek and

Ricker Creek on the Laramie-Albany County line in Section 30, Township 18N, Range 70W, southwest of Iron

Mountain Post Office. Unlike some, he is shown by Bureau of Land Management Records as having made

"cash entry" rather than homesteading. In the 1880's Frederick U. "Fred" Powell arrived. Fred had previously worked for

the Union Pacific and lost one arm in an accident and usually wore a hook. He, nevertheless, was regarded as an expert roper.

At first, Fred, his wife Mary, and

18-month old son Bill settled into the old Strong house about 16 miles east of Laramie City. Mary

Powell had divorced Carlie Wandlus in order to marry Fred. The marrage was not one which was entirely

blissful. Fred had a large scar on the side of his face where Mary had taken a butcher knife to

him. They had with them one yearling heifer and a team of

horses. By that fall, however, they had a cow, eight calves and an additional horse. It was strongly

suspected that acquisition of the additional bovines and horse was not by entirely legitimate means.

Indeed, it turned out that Powell did not have good title to the horse and it had to be returned to

its rightful owner. At least

seven times Powell was charged with stealing horses and neat cattle. Each time he was let go either by

jury, judge, or the prosecutor for lack of evidence. Mary, herself, however, served six months in the

county jail for re-working the brands on some of Dr. Henry L. Stevens' cattle. Fred's entitlement to use the Strong house was no better than his

title to the horse. Mittie Pluscher, nee Richardson, recalled in a 1956 oral history, that one day

the Powells came home to discover that the sheriff had set all of their

belongings outside and locked the house. Fred Powell moved several miles down Horse Creek and homesteaded,

proving up his claim in 1892. The same year, Mary filed for divorce.

Bosler Depot, 1916

In July 1895, Bill Lewis received a letter telling him to leave the area. Shortly thereafter

George Shanton, Tom Cable and Johnny Hardy found Bill Lewis dead

in his corral. Nearby Lewis had a load of beef on his wagon. Bill had three bullet holes in him. He apparently had been

dead about a week. Bill was buried in the cattle yard.

In August, a similar letter was received by Fred Powell. It was haying season and it was necessary

to finish putting up the hay. Additionally, Fred had butchered a beef the night before and it was necessary that

the meat be taken into Cheyenne. Therefore, it was necessary to be out early. Fred had sent his

hired hand, Ross, down to the creek to cut a willow in order to repair one of the hay racks. While Ross was at

the creek, Fred was shot in the chest.

A manuscript fragment by an

unknown author, sympathetic to Tom Horn, describes the killings and their impact [Webmaster's note: If

anyone knows the name of the unknown author, I will be most grateful if you will

E-Mail me.]:

Anonymous Manuscript Fragment

For men who had left cattle alone after getting their first notices had

received no second.

But the day of the deadline came and passed, and the men who had scoffed

at the warnings laughed with satisfaction.

For , with a single exception, nothing had happened to them.

The exception was an Iron Mountain settler named William Lewis

After walking out to his corral that morning, he'd been amazed to

see the dust puff up in front of his feet.

A split second later, the distant crack of a rifle had sounded.

He 'd mounted up immediately and raced with a revolver ready

toward the spot from which he'd estimated the shot had come.

But he had found all of the thickets and points of cover deserted.

There had been no sign of a rifleman and no track or trace to show that

anyone had been near.

Lewis was a man who had made a full - time job of cow stealing

He hadn't even pretended to be farming his spread.

His land had never been plowed.

He had done his rustling openly and boasted about it.

He had received both first and second anonymous notices , and

each time he had accused his neighbors of writing them.

He had cursed at them and threatened them.

He found nothing, but he still refused to give up and move out.

This time Lewis had his own rifle in his hands, and he threw some

answering fire back at the mysterious far - off shot, then spent

most of the day searching out the area.

"I'll be shootin' right back.

I'll be ready next time!" he raged.

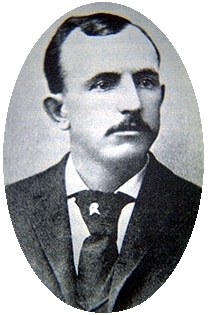

Tom Horn

William Lewis made the rounds of all who lived near

him again, that August morning after a bullet landed at his feet, and once more he accused and threatened everyone.

He was a man , those neighbors testified later, who didn't have a friend

in the world.

He had his chance the very next morning, for exactly the same thing happened again.

"Just let me meet up with that damned bushwhackin' coward face - to - face!"

he exploded.

"That's all I ask."

He never got that chance.

For the unseen, ghostlike rifleman aimed a little higher the third time.

A .30-30 bullet smashed directly into the center of William Lewis' chest.

He slumped against a log fence rail, then tried to lift himself.

Two more shots followed in quick succession, dropping him limp and huddled on the ground.

An inquest was held, and after a good deal of testimony about the anonymous notes,

the county coroner estimated that the shooting had been done from a distance of 300 yards.

Rumors of the offer Tom Horn had made at the Stockgrowers' Association meeting had leaked out by then,

and as a grand jury investigation of the murder got underway, the prosecuting attorney,

a Colonel Baird, ordered that the tall stock detective be summoned for questioning.

It took some time to locate Horn.

He was finally found in the Bates Hole region of Natrona County, two counties away.

[Laramie County] Prosecutor [John C.] Baird immediately assumed he was hiding out there after the shooting and

began preparing an indictment.

But that indictment was never made.

For Tom Horn, it turned out, had a number of rancher and cowboy

witnesses ready and willing to swear with straight faces that

he had been in Bates Hole the day of the killing.

The former scout's alibi couldn't be shaken.

The authorities had to release him.

William McDonald Ranch, Iron Mountain Road, Northeast of Iron Mountain, 1900, photo courtesy Margie McDonald

Schrey

He immediately rode on to Cheyenne, threw a ten - day drinking spree

and dropped some very strong hints among friends.

"Dead center at three hundred yards, that coroner said!" He'd grin.

"Three shots in that fella 'fore he hit the ground.

You reckon there 's two men in this state can shoot like that."

Publicly, he denied everything.

Privately, he created and magnified an image of himself as a hired assassin.

For a blood - chilling ring of terror to the very sound of

his name was the tool he needed for the job he'd promised to do.

The unknown author continues in the description of the killing of Powell:

Tom Horn was soon back at work, giving his secret employers their money's

worth.

A good many beef - hungry settlers were accepting the death of William Lewis

as proof that the warning notes were not idle threats.

The company herds were being raided less often, and cabins and soddies

all over the range were standing deserted.

But there were other homesteaders who passed the Lewis murder off

as a personal grudge killing, the work of one of his neighbors.

The rustling problem was by no means solved.

Even in the very area where the shooting had been done, cattle were

still disappearing. For less than a dozen miles from the unplowed land

of the dead man lived another settler who had ignored the warnings

that his existence might be foreclosed on; a blatant and defiant rustler

named Fred Powell. "Fred was mighty crude about the way he took in cattle,"

his own hired man, Andy Ross, mentioned later.

"Everyone knew it, but he sort of acted like he didn't care who knew it -- even

after them notes came, even after he'd heard about Lewis, even after he'd been

shot at a couple o' times hisself."

On the morning of September 10, 1895, Powell and Ross rose at dawn and began their day's work.

Haying time was close at hand, and they needed some strong branches to repair a hay rack.

Harnessing a team to a buckboard, they drove out to a willow-lined creek about a half-mile off,

then climbed down and began chopping.

Andy Ross had just started swinging an ax at his second willow when the distant blast of a rifle sounded.

He looked around in surprise, then noticed that Fred Powell was clutching his chest.

The hired man ran over to help his boss.

"My God , I'm shot!" Powell gasped.

And he collapsed and died instantly.

Ross had no intention of searching for the assassin.

He heaved the dead man onto the buckboard, yelled and lashed at the

team and got out of there fast.

In her oral history, Mittie Pulscher, recalled Ross "was so scared that he cut the tugs [the traces], jumped

on one of the horses" and rode to the post office on Ben Fay's ranch. Mittie was at the

post office picking up mail. She was asked to have her father, Harry Richardson, and her brothr-in-law,

Elmer LaPash to go down to Fred's body until the sheriff could arrive. Ironically, according to

Mittie, Fred was planning on leaving for Iowa as soon as the haying was completed and the beef

could be sold. He had already sent his son to Iowa to live with Fred's sister.

The anonymous writer continues:

But he brought back the sheriff and several deputies, and to the lawmen the

entire affair seemed a repetition of the Lewis killing. A detailed scouring

of the entire area revealed nothing beyond a ledge of rocks that might

have been the rifleman's hiding place.

There were no tracks of either hoofs or boots.

Not even an empty cartridge case could be found.

Tom Horn

Once again, Tom Horn was the first and most likely suspect, and he was brought

in for questioning immediately.

Once again , he shook his head, kept his face expressionless and his voice very calm,

and had a strongly supported alibi ready.

Later, riding in for some lusty enjoyment of the liquor and professional

ladies of Cheyenne, he laid claim to the killing with the vague insinuations he made.

"Exterminatin' cow thieves is just a business proposition with me",

he'd blandly announce.

"And I sort o' got a corner on the market."

"Tom," a friend asked him once,

"how come you bushwhacked them rustlers.

They wouldn't o' stood no chance with you in a plain, straight - out shoot - down."

He had lots of friends, then as always.

Even as he became widely known as a professional killer, nearly every cowboy

and rancher in Wyoming seemed proud to call him a friend.

No man 's name brought more cheers when it was announced in a rodeo.

He explained, "s'posin' you was a nester swingin' the long rope?

Which would you be most scairt of, a dry-gulchin' or a shoot - down.

Yeah, I can see that", the friend was forced to agree.

"But ... well, it just don't seem sportin' somehow."

The tall sunburnt rustler - hunter stared in amazement.

"I seen a lot o' things in my time.

I found a trooper once the Apache had spread-eagled on an ant hill,

and another time we ran across some teamsters they'd caught, tied

upside down on their own wagon wheels over little fires until

their brains was exploded right out o' their skulls.

I heard o' Texas cattlemen wrappin' a cow thief up in green hides

and lettin' the sun shrink 'em and squeeze him to death.

But there 's one thing I never seen or heard of, one thing I just don't

think there is, and that's a sportin' way o' killin' a man."

The unknown writer continues with a description of the impact of the killings on

rustling in Albany and Laramie Counties:

After the first two murders, the warning notes were rarely ignored

The lesson had been learned. The examples were plain.

When Fred Powell's brother-in-law, Charlie Keane, moved into the dead man's home,

the anonymous letter writer took no chances on Charlie taking up

where Fred had left off and wasted no time on a first notice:

"I IF YOU DON'T LEAVE THIS COUNTRY WITHIN 3 DAYS, YOUR LIFE WILL BE

TAKEN THE SAME AS POWELL'S WAS."

This was the message found tacked to the cabin door.

Keane left, within three days.

All through Albany and Laramie counties, other men were doing the same.

Houses of settlers who'd treated the company herds as a natural resource,

free for the taking, were sitting empty, with weeds growing high in their yards.

The small half - heartedly tended fields of men who'd spent more

time rustling cattle than farming were lying fallow.

No cow thief could count on a jury of his sympathetic peers to free

him any longer.

Jury, judge and executioner were riding the range in the form

of a single unknown figure that could materialize anywhere, at any time,

to dispense an ancient brand of justice the men of the new West had

believed long outdated.

For three straight years, Tom Horn patrolled the southern Wyoming pastures,

and how many men he killed after Lewis and Powell.

If he killed Lewis and Powell will never be known.

Next page: Tom Horn and the Capture of Geronimo, Tom Horn and the Rough Riders.

|