|

Overland Coach, photo by Geoff Dobson

The Overland Stage, while much written about, lasted only about ten years. As discussed later, much

more important to Wyoming were local stage lines which before the coming of railroads

provided transportation to the various parts of the Territory.

Stage service to Wyoming started in the late 1850's. The first effort was by

the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company. Service, however, was discontinued with

the Mormon War. Another effort was made by Hockaday & Legget, who went broke before service could

be started. Thereafter, in June 1858, William Russell commenced service using new

Concord coaches to, among other places, Fort Laramie, under the name of the

Leavenworth & Pike's Peak Express Company. Deeply in debt, in October 1859, he brought in

as partners Alexander Majors and William Waddell.

Employees were required to take an oath:

"I, do hereby solemnly swear, before the Great and Living God, that during my engagement,

and while I am in the employ of Russell, Majors & Waddell,

that I will under no circumstances use profane language; that I will drink

no intoxicating liquors of any kind; that I will not quarrel or fight with

any other employee of the firm and that in every respect I will conduct

myself honestly, be faithful to my duties, and so direct all my acts as

will win the confidence and esteem of my employers, so help me God ."

The company continued its

losses and gave a deed of trust (mortgage) to Ben Holladay (1819-1887), who foreclosed upon the

line in March 1862. For Holladay, the line was a gold mine. At the beginning of the Civil War, the principal

route to the West Coast was the famed Butterfield Mail Route which ran from St. Louis and Memphis to San Francisco, California by way of

El Paso and and Tucson. Although the Butterfield stage took twenty-five days to make the trip, it had the advantage of

not having to cross the Rockies during the winter. Unfortunately, the route was primarily through Confederate

territory. At the beginning of the war, many of the Butterfield stage station and coaches were seized by the

Confederate government. Thus, Holladay had a monopoly on mail destined to and from California until completion of the

telegraph line and the railroad.

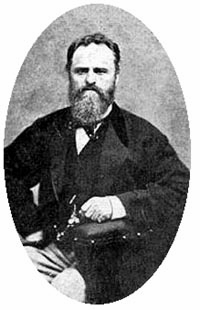

Ben Holladay

Ben Holladay

Operation of the line was very much cash intensive, with the

necessity of having stage stations every 10 to 15 miles, station attendants,

drivers, conductors, smithies, cartwrights, mules, horses, and equipment. Just provisioning the

empire was a task almost beyond imagination. Great wagon trains carrying feed, victuals, supplies, and equipment were used

to provision each division. Holladay had made his original

fortune in freighting goods into Salt Lake City where he had earned the trust of Brigham Young and, thus,

had a ready market. With the advent of the Civil War, professional soldiers were withdrawn from the

West and replaced by volunteers. The result was an upsurgence of Indians depredations, necessitating

the rerouting of the stage line from along the old Oregon Trail to a new route generally following the

Southern Cherokee Trail. Nevertheless, government subsidies for carrying the mail initially made the line

very profitable. On seven routes in the West he received from the government during his first four-year period

$1,896,028. He also had a silent interest in a second contract in which the government paid some

$1,000,000 a year. These sums were in addition to anything he received from carrying passengers.

Holladay with the stage line became the

"King of Stage Lines" with mansions in Oregon, Washington, D.C., and on the Hudson River in

New York. The purpose of the mansion in Washington was to enable Holladay to lobby

Congress as to the subsidies. Later he ventured into steam navigation and attempted the construction

of a railroad and lost most of his fortune.

Granger Stage Station, 1860's

Some questions have been raised as to the date of consruction of the above stage station. Various revisions to the

building were made over the years. Note, as an example, the change in the chimneys in the 1974 photo lower on the page. The renovations have led to

incongruities, such as use of wire nails on some of the interior trim, which some have questioned. Nevertheless, as noted below,

William Henry Jackson visited the station in 1932 and recalled spending time at the Granger Station as a bullwhacker in 1866.

In 1862, Ben Holladay moved stage and mail service from the Oregon Trail to the

Overland Trail in the general vicinity of the Cherokee Trail. the increased traffic required that the station at

the confluence of Ham's Fork and Black's Fork be upgraded and, accordingly,

a new station, pictured above was constructed about four miles from the old one.

In 1866 the line was sold to Wells Fargo and Company but was closed down in 1869 with the

opening of the railroad.

Eugene Ware, who served in the military in Nebraska and what was to become Wyoming, described in his

memoir, The Indian War of 1864, the stage operation:

The stage stations were about ten miles apart, sometimes a little more and

sometimes a little less, according to the location of the ranches. Stores

of shelled corn, for the use of the stage horses, were kept at principal

stations along the line of the route. Intermediate stations between these

principal stations were called "swing stations," where the horses were

changed. For instance, the horses of a stage going up were taken off at

a swing station, and fed; they might be there an hour or six hours;

they might be put upon another stage in the same direction, or upon

a stage returning. It was the policy of the stage company to make the

business as profitable as possible, so it did not run its coaches until

each coach had a good load, and they were most generally crowded with

persons both on the inside and on top. Sometimes a stage would be almost

loaded with women. From time to time stage company wagons went by loaded

with shelled corn for distribution as needed at the swing stations. All

of the coaches carried Government mail in greater or less quantities.

Occasionally when the mail accumulated, a covered wagon loaded with mail

went along with the coaches. These coaches were billed to go a hundred

miles a day going west; sometimes they went faster. Coming east the

down-grade of a few feet per mile enabled them to make better time.

They went night and day, and a jollier lot of people could scarcely

be found anywhere than the parties in these coaches.

The coaches were all built alike, upon a standard pattern called

the "Concord Coach," with heavy leather springs, and they drove from

four to six horses according to their load. The drivers sat up in the

box, proud as brigadier-generals, and they were as tough, hardy and

brave a lot of people as could be found anywhere. As a rule they were

courteous to the passengers, and careful of their horses. They made

runs of about a hundred miles and back. I got acquainted with many

of them, and a more fearless and companionable lot of men I never met.

There seemed to be an idea among them that while on the box they should

not drink liquor, but when they got off they had stories to tell, and

generally indulged freely. They gathered up mail from the ranches, and

trains, and travelers along the road, and saw that it reached its

destination. They had but very few perquisites, but among others was

the getting furs, principally beaver-skins, and selling them to passengers.

Most of them had beaver-skin overcoats with large turned-up collars.

We soon understood the benefits of these collars, and the officers of our

post put large beaver collars on their overcoats, and the men of the

company fitted themselves out with tanned wolfskin collars, which were

equally as good. Wolves were so numerous that there was quite an

industry in shooting or poisoning them, and tanning their skins for

the pilgrim trade.

The accomodations at the various stage stations maintained by the line received mixed reviews. The British adventurer Sir Richard Burton

(1821-1890)

on his 1860 stage trip across the west, reported of the original Green River station:

"The station had the indescribable scent of a Hindu village,

which appears to be the result from burning of bois de vache and a few cows

which were so lively it was impossible to milk them. We supped comfortably on

salmon, trout, buffalo-berry jelly and ‘Valley Tan’ whiskey."

Sir Richard Burton August 21, 1860 6:30 PM. [Writer's note: bois de vache, cow chips. Sir Richard in his

1862 The City of the Saints, and Across the Rocky Mountains to California, recounted his

journey and noted that meat cooked over chips did not require pepper. But Sir Richard was

not the only one to make that observation. Warren Angus Ferris, a trapper for the

American Fur Company, in his ROCKY MOUNTAINS, A Diary of Wanderings on the sources of

the Rivers Missouri, Columbia, and Colorado,

from February, 1830, to November, 1835, observed:

Since leaving the Loup Fork we have seen very little timber, and latterly none at all. We, however, hitherto found plenty of

driftwood along the banks of the river, but to-day, the nineteenth, there

is not a stick of any description to be seen, and as the only resource, we

are compelled to use as a substitute for fuel, the dried excrement of buffalo,

of which, fortunately, the prairie furnishes an abundant supply. I do not,

by any means, take it upon myself to defend the position, but certainly

some of the veterans of the party affirm that our cooking exhibits a

decided improvement, which they attribute to this cause, and to no other.

That our steaks are particularly savoury I can bear witness.

Of "Valley Tan," a vile distillate of wheat and potatoes, George Lathrop, later a driver on the

Cheyenne-Blackhills Stage, thought it "was made of horned toads and Rocky Mountain rattlesnakes." He

noted in his 1915 Memoirs, after it got to working on him, he felt that he "could

whip all the Sioux Indians on the plains or any of the bull-whackers who had been in the

habit of talking back to me. I want to tell you that Valley Tan was the forty-rod stuff." Horace Greeley described local

whiskey:

And such liquor! True, I

have not tasted it; but the smell I could not escape;

and I am sure a more wholesome potable might be compounded

of spirits of turpentine, aqua fortis, and steeped

tobacco. Its look alone would condemn it—soapy,

ropy, turbid, it is within bounds to say that every pint

of it contains as much deadly poison as a gallon of pure

whisky. And yet fully half the earnings of the working

men (not including the Mormons, of whom I have

yet seen little) of this whole region are fooled away on

this abominable witch-broth and its foster-brother tobacco,

for which they pay $1 to 2 50 per pound ! The

log-tavern-keeper at Weber, of whom our mail-boys

bought their next supply of "rot," apologetically observed, "

There a'n't nothing bad about this whisky;

the only fault is, it isn't good." I back that last assertion

with my whole heart. An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859, C. M. Saxton, Barker & Co., New York, 1860.]

Overland Trail ruts, north of Baggs, photo by Geoff Dobson, 2003

Sir Richard had previously explored parts of Africa and visited Mecca. Edward Wright in his 1906

The Life of Sir Richard Burton, Everett and Co., London, noted the

purpose of Sir Richard's trek:

It was natural that, after seeing the Mecca of the Mohammedans, Burton

should turn to the Mecca of the Mormons, for he was always attracted by the

centres of the various faiths, moreover he wished to learn the truth about a

city and a religion that had previously been described only by the biassed.

One writer, for instance-- a lady--had vilified Mormonism because

"some rude men in Salt Lake City had walked over a bridge before her."

It was scarcely the most propitious moment to start on such a journey. The

country was torn with intestine contentions. The United States Government

were fighting the Indians, and the Mormons were busy stalking one another

with revolvers. Trifles of this kind, however, did not weigh with Burton.

After an uneventful voyage across the Atlantic, and a conventional journey

overland, he arrived at St. Joseph, popularly St. Jo, on the Missouri. Here

he clothed himself like a backwoodsman, taking care, however, to put among

this luggage a silk hat and a frock coat in order to make an impression

among the saints.

In Salt Lake City, Sir Richard secured an audience with Brigham Young and offered to

convert to Mormonism. Wright wrote, "Young replied, with a smile, 'I think

you've done that sort of thing once before, Captain.' So Burton was unable

to add Mormonism to his five or six other religions."

Granger Station on Old U.S. 30, approx. 1974.

Sir Richard gave a far less complementary review of the orignial station at

Ham's Fork:

The station was kept by an Irishman and Scotsman "David Lewis". It was a

disgrace. The squalor and filth were worse almost than the two -- Cold Springs

and Rock Creek -- which had called our horrors, and which had always seemed to be the

ne plus ultra of Western discomfort. The shanty was made of dry stone piled up against a dwarf

cliff to save backwall and ignored doors and windows. The flies -- unequivocal sign of

unclean living! -- darkened the table and covered every thing put

upon it; the furniture, which mainly consisted of the defferent parts of wagons, was

broken, and all in disorder; the walls were impure, the floor filthy. The reason was

at once apparent. Two Irish women, sisters, were married to br. Dawvid, and the house was full of "childer,"

the nosiest and most rampageous of their kind. I could hardly look upon the scene

without disgust. * * * * Moreover, I could not but notice that, though

the house contained two wives, it boasted only of one cubile, and had only one cubiculum.

Such things would excite no surprise in London or Naples, or even in many of

the country parts of Europe; but here, where ground is worthless, where

building material is abundant, and where a few hours of daily labor would have made

the house look at least respectable, I could not wonder at it. My first impulse was

to attribute the evil, uncharitably enough, to Mormonism; to renew, in fact, the

stock-complaint of nineteen centuries' standing --

"Foecunda culpae secula nuptias

Primum inquinavere, et genus et domus."

[Writer's note, Loosely translated: A fruitful marriage gives birth to a dirty home.]

Ruins of Point of Rocks Station

Samuel Clemens in Roughing It described the accommodations and napery furnished to

passengers of the stage line:

The station buildings were long, low huts, made of sundried,

mud-colored bricks, laid up without mortar (adobes, the Spaniards

call these bricks, and Americans shorten it to 'dobies). The roofs,

which had no slant to them worth speaking of, were thatched and then

sodded or covered with a thick layer of earth, and from this sprung

a pretty rank growth of weeds and grass. It was the first time we had

ever seen a man's front yard on top of his house. The building consisted

of barns, stable-room for twelve or fifteen horses, and a hut for an

eating-room for passengers. This latter had bunks in it for the

station-keeper and a hostler or two. You could rest your elbow on

its eaves, and you had to bend in order to get in at the door.

In place of a window there was a square hole about large enough

for a man to crawl through, but this had no glass in it. There was

no flooring, but the ground was packed hard. There was no stove,

but the fire-place served all needful purposes.

Fireplace, Point of Rocks Station, photo by Geoff

Dobson

Clemens continues:

There were no shelves, no cupboards, no closets. In a corner stood an open

sack of flour, and nestling against its base were a couple of black

and venerable tin coffee-pots, a tin teapot, a little bag of salt,

and a side of bacon.

By the door of the station-keeper's den, outside, was a tin wash-basin,

on the ground. Near it was a pail of water and a piece of yellow bar soap,

and from the eaves hung a hoary blue woolen shirt, significantly -- but

this latter was the station-keeper's private towel, and only two persons

in all the party might venture to use it -- the stage-driver and the

conductor. The latter would not, from a sense of decency; the former

would not, because did not choose to encourage the advances of a

station-keeper. We had towels -- in the valise; they might as well

have been in Sodom and Gomorrah. We (and the conductor) used our

handkerchiefs, and the driver his pantaloons and sleeves. By the door,

inside, was fastened a small old-fashioned looking-glass frame, with

two little fragments of the original mirror lodged down in one corner

of it. This arrangement afforded a pleasant double-barreled portrait

of you when you looked into it, with one half of your head set up a

couple of inches above the other half. From the glass frame hung the

half of a comb by a string -- but if I had to describe that patriarch

or die, I believe I would order some sample coffins.

Nor were the furnishings of the stations any better. Clemens describes the

furnture:

The furniture of the hut was neither gorgeous nor much in the way.

The rocking-chairs and sofas were not present, and never had been,

but they were represented by two three-legged stools, a pine-board

bench four feet long, and two empty candle-boxes. The table was a

greasy board on stilts, and the table-cloth and napkins had not

come--and they were not looking for them, either. A battered tin platter,

a knife and fork, and a tin pint cup, were at each man's place, and the

driver had a queens-ware saucer that had seen better days. Of course this

duke sat at the head of the table. There was one isolated piece of table

furniture that bore about it a touching air of grandeur in misfortune.

This was the caster. It was German silver, and crippled and rusty, but

it was so preposterously out of place there that it was suggestive of a

tattered exiled king among barbarians, and the majesty of its native

position compelled respect even in its degradation.

There was only one cruet left, and that was a stopperless, fly-specked,

broken-necked thing, with two inches of vinegar in it, and a dozen

preserved flies with their heels up and looking sorry they had invested

there.

Next Page: The Overland Stage continued.

|