Snake River and the Tetons, Ansel Adams, The Mural Project, 1942.

Compare with modern photo of same scene at botton of page. The Mural Project was commissioned in 1941

by Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, to provide photographs of national parks, monuments, Indian

lands and reclaimation projects

under the jurisdiction of the Department. Because of World War II the project was

discontinued.

The gravel and sandbar in the photo is the site of one of the great unsolved mysteries of

Jackson Hole and the Tetons. The mystery gave rise to the name of the

bar, Deadman's Bar. Following the end of the California Gold Rush prospectors

fanned across the Rocky Mountain West seeking gold pockets or the mother lode. As noted on other pages,

gold was discovered in the 1860's in Montana and at South Pass in Wyoming. In

1874 gold was discovered in the Black Hills. Thus, it would not have been

unexpected that prospectors should explore the shores of the Snake River in

Jackson's Hole for aluvial gold. In the flat area built up on the north side of the river (on the right) in 1886, four

prospectors from Montana set up camp.

Jackson Lake, photo by Wm. H. Jackson, 1892, tinted by Detroit Publishing Company, 1902.

Jackson Lake, photo by Wm. H. Jackson, 1892, tinted by Detroit Publishing Company, 1902.

Although the President of the United States and his party had ridden through three years before, settlers

in the valley were few. Thus, supples had to be obtained from the other side of the

mountains in Pierre's Hole, Idaho, now known as the Teton Basin.

The valley was virgin territory for prospectors. In the popular mind, perhaps, panning for gold is envisioned as a means of

collecting gold. It is in reality a method of prospecting. The aluvial miner follows a trace of

yellow which is found by panning, hoping the trace will lead him to the mother pocket or lode from

wence the gold particles in the sand and gravel bars had been washed by flood or the action of the river.

In 1905, Century Magazine published Jack London's classic short story

All Gold Canyon. In the story about the fight to the death between a prospector and a

claim jumper, London explains the process of panning and finding gold laden

pockets:

He crossed the stream below the pool, stepping agilely from stone to

stone. Where the sidehill touched the water he dug up a shovelful of dirt

and put it into the gold-pan. He squatted down, holding the pan in his two

hands, and partly immersing it in the stream. Then he imparted to the pan

a deft circular motion that sent the water sluicing in and out through the

dirt and gravel. The larger and the lighter particles worked to the surface,

and these, by a skilful dipping movement of the pan, he spilled out and over

the edge. Occasionally, to expedite matters, he rested the pan and with his

fingers raked out the large pebbles and pieces of rock.

The contents of the pan diminished rapidly until only fine dirt and the

smallest bits of gravel remained. At this stage he began to work very

deliberately and carefully. It was fine washing, and he washed fine and

finer, with a keen scrutiny and delicate and fastidious touch. At last the

pan seemed empty of everything but water; but with a quick semicircular

flirt that sent the water flying over the shallow rim into the stream, he

disclosed a layer of black sand on the bottom of the pan. So thin was this

layer that it was like a streak of paint. He examined it closely. In the

midst of it was a tiny golden speck. He dribbled a little water in over the

depressed edge of the pan. With a quick flirt he sent the water sluicing

across the bottom, turning the grains of black sand over and over A second

tiny golden speck rewarded his effort.

The washing had now become very fine--fine beyond all need of ordinary

placer-mining. He worked the black sand, a small portion at a time, up the

shallow rim of the pan. Each small portion he examined sharply, so that his

eyes saw every grain of it before he allowed it to slide over the edge and

away. Jealously, bit by bit, he let the black sand slip away. A golden

speck, no larger than a pin-point, appeared on the rim, and by his

manipulation of the riveter it returned to the bottom of tile pan. And in

such fashion another speck was disclosed, and another. Great was his care

of them. Like a shepherd he herded his flock of golden specks so that not

one should be lost. At last, of the pan of dirt nothing remained but his

golden herd. He counted it, and then, after all his labor, sent it flying

out of the pan with one final swirl of water.

Panning for gold, 1940. Photo by Lee Russell courtesy Library of Congress.

Should the prospector be searching for a pocket of of rich gold bearing gravel in

a hill overlooking the stream, the process is repeated, first upstream until no gold is found. Then down stream.

In this manner the miner determines the limits along the river in which gold may have

been washed from the adjacent hill. Up slope, the miner then digs holes parallel to the

river, and again washes a sample from each hole, again determining the limits of the

area in which the tiny particles are found. And again up slope, the process is

repeated. A pattern emerges pointing to the area from which the gold has come. Hopefully,

a pocket of eroded gold-bearing quartz will be found. If, instead, the prospector is seeking

a vein of ore from which rock may have eroded into the steam, the process is repeated

following the stream and its tributaries until the mother lode is located.

Through the summer, the four

prospectors similarly toiled. Once, the four crossed Teton Pass to Pierre's Hole to seek

supplies from a rancher, Emile Wolff. Some supplies were paid for with a $20.00 gold piece. Ten

Dollars was put up as security for a saw to be used to construct a raft.

Thus, the prospectors were not without funds. Wolff, himself, would later settle

in Jackson Hole, proving up his homestead in 1906 and buying additional land

in 1912. One of the miners proved to

have been a friend of Wolff's. Another was a large man. A third was small and was missing

two fingers. The fourth going by the name of John Tonner was dark complectioned.

In August, Tonner appeared at Wolff's ranch on foot. He explained that the others had gone off

hunting for the winter's supply of game. Tonner was given employment, but strangely always

wore his gun.

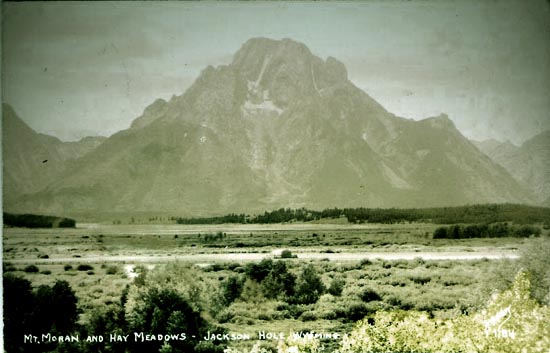

Sometime that summer, a party coming down the river found the deserted mining camp. Below the steep bluff

visible in the above photo, the party found the remains of the three prospectors. One had been

shot in the back and the other two with axe blows to the head. A sheriff's

posse from the county seat in Evanston, 220 miles away, thought it likely that

Tonner had killed his compatriots. The jury, however, disagreed. There simply was no direct evidence connecting

Tonner to the bloody murders. Tonner disappears. Did Tonner kill his fellows. If he had, why

was he on foot? Would not he have had use of the pack animals? Would not he have had some of the

party's money? Although traces of yellow have been found in Jackson Hole, no productive

finds have been recorded. Thus, prospectors came to the valley and departed. Only one, Jack Davis who was rumored

to have killed a man in Virginia City, Montana, stayed, holding a

claim on the Snake near Bailey Creek. When he died on March 25, 1911, only about

$12.00 in gold was found in his cabin. Were the three killed by claim jumpers? But if there was

no gold, why were the three killed? Remnants of a half-mile long sluice canal

have been found at the site. But if no gold were found, why would the effort have

been made to constuct the sluice? For if there were no trace of color, the party would have moved

on? Thus, remains the mystery? Is there gold in the valley? Possibly. And who killed the

three?

Snake River Overlook, 1997

Nor would the death of the three prospectors be the only mysterious death to haunt northern

Jackson Hole. In distant New York City at busy Riverside Drive and West 76th Street, scarcely noticed by the

thousands of motorists who pass by, is a reminder of three more such deaths, an elaborate horse trough. The trough is topped by a

soring eagle which looks much like the eagle above the backbar of Laramie's Buckhorn Saloon. The trough, now planted with

flowers, was bequeathed to the City of New York by Robert Ray Hamilton, a great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton and

great great great grandson of Gen Philip Schulyer.

The horse trough cost some $10,000.00 (in 1906 dollars) to build. It was designed by Warren and Wetmore, the architects for the

facade of New York's Grand Central Station. And

from the events surrounding the death of Hamilton, Signal Mountain at the northern end of the

Hole takes its name.

The Honorable Robert Ray Hamilton

The Honorable Robert Ray Hamilton

|

In 1889, Hamilton, a wealthy Republican Party activist, former New York State Assemblyman, and a leading

member of New York's elite, found himself in

the center of a scandal fueled by the New York World which titilated the newspaper readers of the nation. A young lady of dubious reputation,

whom Hamilton had met in a gilded New York parlor house, had

convinced Hamilton that a child was his. Thus, Hamilton secretly had taken the lady for his wife and lavished large amounts of

money upon her. Indeed, the amount of money bestowed was such that it came to the

attention of the New York Times which reported that he had borrowed more than $50,000.00 mortgaging his

various properties. To tend to the

child, Hamilton employed a nurse. In a brawl, the new Mrs. Hamilton stabbed the nurse.

The resulting investigation revealed that the new Mrs. Hamilton had gone under a variety of

aliases, was already married, and the child was a foundling who had been purchased by the new Mrs. Hamilton for

$10.00 or $15.00 from a midwife. The effort to murder the nurse was apparently as a result of the nurse having

figured out the situation and threatening to reveal all to Hamilton. The trial of Evangeline Hamilton in a New Jersey court was

sensational and reported nationally. The effect on Hamilton was dramatic. The New York Times noted:

Aug. 30, 1889.

Mr. Hamilton's appearance has undergone

such changes recently that it would be hard

even for his acquintences to rcognize him

at first glance. He is haggard, unkempt, and there is

a wild look in his eyes that every one who has

seen him has not failed to notice.

He is absolutely under the baneful influence exerted by

the woman, as is shown in his conduct toward

her since her arrest. His friends and

people generally in this city can find no

other explanation for his doings during

the last three years than that he has become a

monomaniac.

[Writer's note: "monomania," a mental disorder in which an otherwise rational person is obsessed with

one subject.]

In May 1890, to overcome his depression, Hamilton with some friends undertook a hunting trip to

the American West. In Jackson's Hole, Hamilton became a friend of John D. Sargent who had settled on the

east shore of Jackson Lake in 1887. The two decided to build a hotel which would cater to eastern

hunting parties. In August, Hamilton went out hunting with his horse and dog. When Hamilton did not return,

searching parties were sent out. It was agreed that if Hamilton were found, a signal fire would be lit on the

summit of what is now called "Signal Mountain." On September 2 after three days of searching, Hamilton's

horse and dog were found. Strapped to the Horse's saddle which had slipped over were the partially

eaten remains of an antelope. The dog had apparently survived by dining on the antelope. A search of the

nearby Snake River found Hamilton's body jammed against some

trees which had fallen into the river. The body was not recognizable. Identification was made from clothing, watch, and a book of trout

flies with the name Hamilton inside. The coroner's jury determined that

Hamilton had drowned. There were those who believed, including Hamilton's putative wife (the annullment proceeding were still pending), that

Hamilton was not dead; that Hamilton's death was a ruse; that the body was that of someone else. There were the

usual "Hamilton sigtings." A New York newspaper dispatched an investigator to Wyoming to have

the body disinterred. The New York World reported that the examination revealed a fracture of the left leg matching a

previous injury sustained by Hamilton Eventually, New Jersey courts determined that Hamilton was in fact dead. The New York

Courts found that the putative marrage was void as bigamous. See In the Matter of Hamilton, 2 Cases in the Surragates' Courts 472 (1891);

In Re Hamilton, 27 N.Y.S. 813 (1894). The bequest of the horse fountain was sustained, In the Matter of Robert Ray Hamilton, 148 N.Y. 310 (1896).

In 1897, Sargent's wife, Adelaide, was found brutally beaten from the effects of which

she died. Allegedly, prior to her death, she accused her husband of having killed Hamilton.

Thus, local ranchers have alays suspected that Hamilton had been killed by Sargent to gain control over

the property Sargant and Hamilton owned together.

Sargent took his children east but returned in 1899 and was charged with the second degree murder of his wife. While held in the Uinta County Jail in Evanston,

he was determined to have become permanently insane. He was released for lack of evidence. His father took custody of

the children and disowned him. Sargent returned to

Jackson Hole. With no support from his family, Sargent eked out a living running a small store, acting as an

agent for the Victor Talking Machine Company, and

renting out a boat which he brought in on the old Conant Trail from Idaho. Later he spent three years in California where he met his second wife, Edith.

Sargent returned to the old cabin which he and

Hamilton built. There, Edith would allegedly play the violin outside in the nude.

Edith Sargent playing violin.

On July 24, 1913, while

Edith was in the east, Sargent's body was found dead from a revolver shot, an apparent suicide.

Edith wrote of the

Grand Tetons:

The ages pass and men die fast.

But still the Tetons stood.

In stately silence to the last.

Wraught by no human hands. |

Edith spent the last three years of her life in the Manhatten [N.Y] State Hospital.

Mt. Moran and the Hay Meadows, 1941.

For more on the death of Robert Ray Hamilton, see the writer's full length book available for free download.

Cover, "Murder in the Tetons."

Table of Contents Murder in the Tetons.

Murder in the Tetons.

Next page, The first ascent of Grand Teton.

|