|

In the spring of 1877, the order came forth that the Wallowa Band of the Nez Perce were to

move from their ancestral home in the Wallowa Valley of Oregon to the Lapwai Reservation. The

Nez Perce had been repeatedly promised portions of the

Wallowa Valley by the Great Father. Indeed, in 1855, Chief Joseph's father, Joseph the Elder, had helped lay out a

reservation for the Nez Perce, but in 1863, following a gold rush, the government shrank the reservation to

one-tenth its size and demanded that Joseph the Elder sign a new treaty to

recognize the revised boundaries. Joseph the Elder refused to sign. The old chief had

early converted to Christianity and was an elder in the Church. In disgust he burned the

American flag and his bible. In 1871, the old chief died and his son was selected as the

new Chief. In 1873, President Grant issued an order permitting the

Nez Perce to remain in their ancestral home. In the Wallowa, the Nez Perce had for generations raised

prized apploosas [from the Palouse River in the home territory of the Nez

Perce], cattle, and farmed.

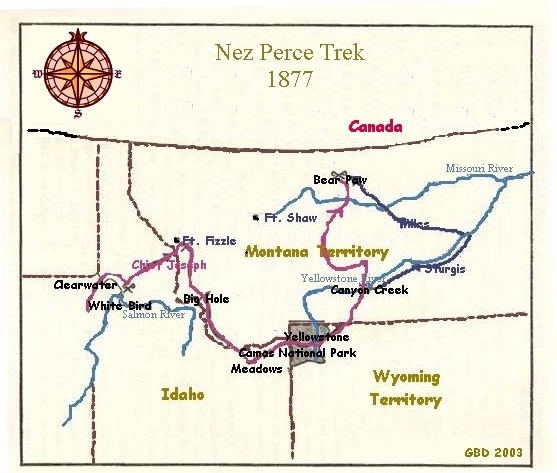

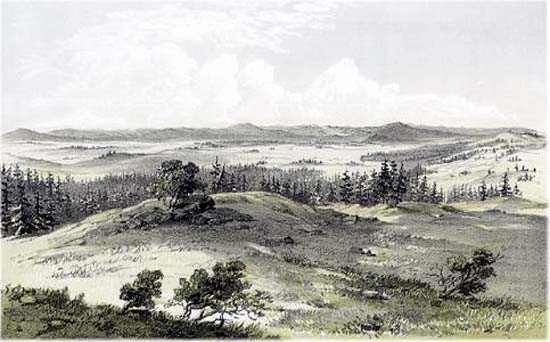

Headwaters of the Palouse, lithograph by

John Mix Stanley based on sketch by Gustavus Sohon, 1860

General Miles later to wrote in his 1896 Recollections:

In our treaty relations extravagant and yet sacred promises have been given by the

highest authorities, and these have been frequently disregared. The intrusions of the

white race and non-compliance with treaty obligations, have been followed by

atrocities that could only satisfy a savage and revengeful spirit.

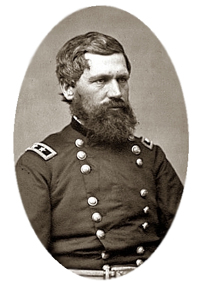

Oliver Otis Howard

Oliver Otis Howard

Brig. General Oliver Otis Howard, after whom Howard University is named, set the deadline for the move to Lapwai at June 14. As the Nez Perce were packing for the

move, White raiders stole several hundred of the horses including stud stallions. Thus, four days before the

deadline, the chiefs of the tribe gathered at Tepahlewam near present day Grangeville, Idaho. There, notwithstanding the

latest White outrage, White Bird, Toohoolhoolzote, and Looking Glass urged compliance with the

government's decree. Shore Crossing and Red Moccasin Tops urged war. Shore Crossing's father had been

murdered by a White. Chief Joseph was absent, at home awaiting the birth of a child. Yet when the conclave ended, the

tribe was seemingly acquesent to the move. But upon his return to home, bolstered by the heart that

alcohol gives, Shore Crossing with several others determined upon revenge for the death of his father. Not finding the

culprit, two other Whites were killed and another wounded. Toohoolhoolzote joined in raids upon other Whites.

Joseph realized that a move to Lapwai would no longer placate the Army.

First the Nez Perce sought the help of the Crow, but the Crow helped the Army. Yellow Wolf remembered:

I do not understand how the Crows could think to help the soldiers. The were fighting against their best friends! Some

Nez Perces in our band had helped then whip the Sioux who came against them only a few snows before. This was

why Chief Looking Glass had advised going to the Crows, to the buffalo country. He

though Crows would help us, if there was more fighting.

Thus, came the realization that it would be necessary to seek refuge in

Canada. To the northeast towards Lolo Pass Joseph

led his band consisting of perhaps 300 warriors and 1700 women, children and elderly. At White Bird Canyon soldiers of the First Cavalry engaged the Indians and were decisively defeated. On July 11,

Gen. Howard again cought up with the Nez Perce at the Clearwater River. There, the Fourth Artillery accidently fired on

the Infantry and the Indians again eluded the Army. In Lolo pass the Army constructed a fortification, but the military allowed

the Indians to pass. Thus, the fort was thereafter known as "Fort Fizzle." In Stevensville, the Indians replenished supplies by

purchase from local merchants, paying in gold coin. Joseph forbade the purchase of alcohol.

At Big Hole, John Gibbon coming from Fort Shaw, cought up with Joseph. There, the tables were turned and

Gibbon was beseiged for two days by the Indians. In the face of a relief column from Gen. Howard, the

Indians again withdrew but not before capturing 2,000 rounds of amunition. Indian losses, however, included

Shore Crossing and Red Moccasin Tops.

The Nez Perce headed south towards Yellowstone National Park. At Camas Meadows another encounter

rsulted in Howard losing his pack mules. The Nez Perce, as discussed on the Yellowstone pages, passed through the Park, capturing some tourists who

were later released.

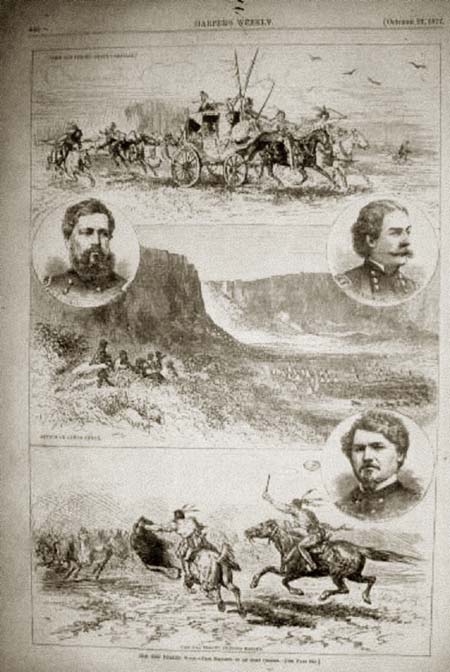

Top panel, stolen mail coach; Middle panel Battle of

Caņon Creek; Bottom panel, Nez Perce on horses; Upper left, General O. O. Howard; Upper right,

Gen. Nelson A. Miles; Lower right, Col. Samuel D. Sturgis. Page from Harper's

Weekly, October 17, 1877.

Top panel, stolen mail coach; Middle panel Battle of

Caņon Creek; Bottom panel, Nez Perce on horses; Upper left, General O. O. Howard; Upper right,

Gen. Nelson A. Miles; Lower right, Col. Samuel D. Sturgis. Page from Harper's

Weekly, October 17, 1877.

At Canyon Creek between present day Billings and Laurel, the

Indians encountered Col. Samuel Sturgis who was cautious with most of the men

fighting on foot. Capt. Benteen made one cavalry charge. The Nez Perce again made good their escape. Army loses were

four killed, including two that had survived at Reno's Hill at Little Bighorn, and 12 wounded. At Bear Paw,

forty miles from the protection of the Great Mother, the Indians were cut off and for five days the Indians were

besieged by General Miles who had come from Ft. Keogh. The Nez Perce repulsed multiple attacks. Looking Glass was killed, Chief Ollokot, Lone Bird and

Lean Elk were gone. On October 5, under a flag of truce, Chief Joseph surrendered, telling Chapman, the interpreter:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before -- I have it

in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Too-hul-hul-sit is dead.

Looking Glass is dead. He-who-led-the-young-men-in-battle is dead [Joseph's brother, Ollokot].

The chiefs are all dead. It is the young men now who say 'yes' or 'no.'

My little daughter has run away upon the prairie. I do not know where to

find her-perhaps I shall find her too among the dead. It is cold and we

have no fire; no blankets. Our little children are crying for food but we

have none to give. Hear me, my chiefs. From where the sun now stands,

Joseph will fight no more forever." (As quoted by Charles Erskine Scott Wood, Howard's Aide de Camp)

Chief Joseph later explained the surrender:

My people were divided about surrendering. We could have escaped from Bear Paw Mountain if we had left our wounded,

old women and children behind. We were unwilling to do this. We had never

heard of a wounded Indian recovering while in the hands of white men. * * * *

General Miles had promised that we might return to our own country with what stock we had

left. I though we could start again. I believed General Miles, or I never would have surrendered.

[The promise by Miles was based orders to return the Indians to the Department of Columbia which

included Idaho. Howard contended that no promises were made.]

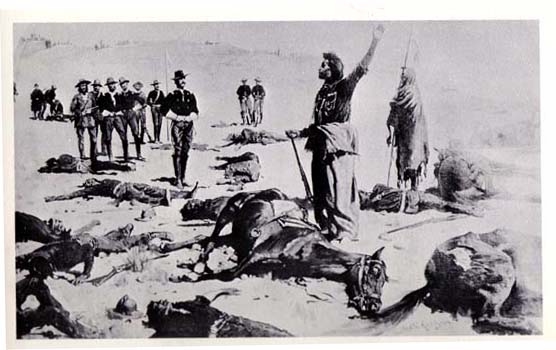

Surrender of Chief Joseph, Frederic Remington

Notwithstanding Miles' promise, on orders of General Sherman, Chief Joseph and 337 others was shipped off to a

place in Oklahoma, that the Nez Perce soon called Eeikish Pah, the "Hot Place." There

a cemetery with a hundred graves was set aside just for the children. [Writer's note: Eeikish Pah can have two meanings:

the literal meaning or one of religious significance, i. e. Purgatory.]

Chief Joseph, 1892

Chief Joseph, 1892

Chester Anders Fee in his 1936 Chief Joseph, the Biography of a Great

Indian quoted Chief Joseph as saying on a visit to Washington:

I cannot understand how the Government sends a man out to fight us, as it

did General Miles, and then

breaks his word. Such a government has something wrong about it. I cannot

understand why so many chiefs are allowed to talk so many different ways,

and promise so many different things. I have seen the Great Father Chief

[President Hayes]; the Next Great Chief [Secretary of the Interior]; the

Commissioner Chief; the Law Chief; and many other law chiefs [Congressmen]

and they all say they are my friends, and that I shall have justice, but

while all their mouths talk right I do not understand why nothing is done

for my people. I have heard talk and talk but nothing is done. Good words

do not last long unless they amount to something. Words do not pay for my

dead people. They do not pay for my country now overrun by white men. They

do not protect my father's grave. They do not pay for my horses and cattle.

Good words do not give me back my children. Good words will not make good

the promise of your war chief, General Miles. Good words will not give my

people a home where they can live in peace and take care of themselves.

I am tired of talk that comes to nothing. It makes my heart sick when I

remember all the good words and all the broken promises. There has been

too much talking by men who had no right to talk. Too many

misinterpretations have been made; too many misunderstandings have come

up between the white men and the Indians. If the white man wants to live

in peace with the Indian he can live in peace. There need be no trouble.

Treat all men alike. Give them the same laws. Give them all an even chance

to live and grow. All men were made by the same Great Spirit Chief. They

are all brothers. The earth is the mother of all people, and all people

should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect all rivers to

run backward as that any man who was born a free man should be contented

penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases. If you tie a horse

to a stake, do you expect he will grow fat? If you pen an Indian up on a

small spot of earth and compel him to stay there, he will not be contented

nor will he grow and prosper. I have asked some of the Great White Chiefs

where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in

one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot

tell me.

Gibbon was

wounded in the Battle of Big Hole. Subsequently, Chief Joseph and Gibbon became friends.

In 1895, Gibbon was elected commander-in-chief of The Loyal Legion of the United States,

a Civil War Veteran's organization comprised of Union officers.

Later, C. E. Wood, Gen. Howard's aide, summed up Chief Joseph's life: "I

think that, in his long career, Joseph cannot accuse the United States of one single act

of justice."

Next page: Wounded Knee.

|