| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Presidential visits, Theodore Roosevelt, Chester A. Arthur; John Colter, the Earl of Dunraven. |

|

| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Presidential visits, Theodore Roosevelt, Chester A. Arthur; John Colter, the Earl of Dunraven. |

|

|

|

|

About This Site |

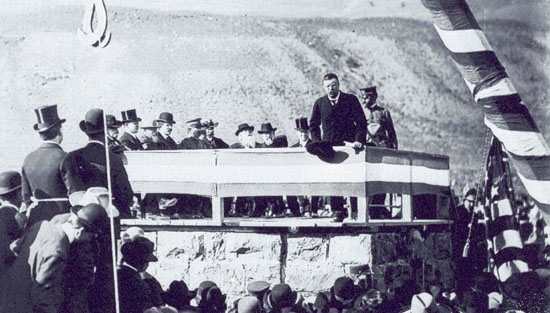

Dedication of cornerstone for the entrance arch by President Roosevelt, April 1903. Photo courtesy of Yellowstone National Park Archives.

John Colter reputedly was the first European American to see the wonders of Yellowstone. John Colter had been with the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery, but had continued to trap and explore the Rocky Mountain west following the expedition's return. In 1807, Colter joined with Manuel Lisa in Lisa's expedition to the Bighorn. During the winter of 1807-08, Colter ascended the Bighorn to the Wind River Basin, crossed over to the Teton Basin, explored Yellowstone, and back to Manuel's fort. Thus, Colter's trek is the first documented exploration of present day Wyoming. Trappers for the Northwest Company or the Hudson's Bay Company may have preceeded Colter. Jules DeFoe, a trapper for the Northwest Company, was in present day Idaho as early as 1789. In 1855, the discovery of an inscription in French bearing the name "Lecarne, dated in the 1700's, was reportedly found in Utah. An 1811 map showing the Great Salt Lake indicated that it was based on the report of a traveler from the 1790's. Near Bondurant, Wyoming, a lichen overgrown inscription on a rock with the initials "M A" and the date 1791 was reportedly found in 1961. In the summer of 1808, Colter continued his trapping in the company of John Potts who also had served with the Corps of Discovery. In an encounter with Blackfeet Indians, Potts was killed. Colter was captured by the Indians, stripped naked, was given a two or three hundred yards headstart, and permitted to run for his life chased by various warriors across a plain abounding with prickly pear. One of the Indians armed with a spear nearly caught him and fell whilst throwing the spear, breaking the spear which Colter grabbed and used to dispatch his assailant. Colter was then able to hide beneath driftwood in a river. John Bradbury in his 1819 Travels in the Interior of America, in the Years 1809, 1810, and 1811 described Colter's escape: Scarcely had he secured himself, when the Indians arrived on the river, screeching and yelling, as Colter expressed it, "like so many devils." They were frequently on the raft during the day, and were seen through the chinks by Colter, who was congratulating himself on his escape, until the idea arose that they might set the raft on fire. In horrible suspense he remained until night, when hearing no more of the Indians, he dived from under the raft, and swam silently down the river to a considerable distance, when he landed, and travelled all night. Although happy in having escaped from the Indians, his situation was still dreadful: he was completely naked, under a burning sun; the soles of his feet were entirely filled with the thorns of the prickly pear; he was hungry, and had no means of killing game, although he saw abundance around him, and was at least seven days journey from Lisa's Fort, on the Bighorn branch of the Roche Jaune River. These were circumstances under which almost any man but an American hunter would have despaired. He arrived at the fort in seven days, having subsisted on a root much esteemed by the Indians of the Missouri, now known by naturalists as psoralea esculenta. [Writer's notes: Psoralea esculenta, Indian Breadrood, sometimes also referred to as breadroot scurf pea or prairie turnip; Roche Jaune River, the Yellowstone.] Other early trappers made it into the Yellowstone. In his 1895 work on Yellowstone National Park, Hirem M. Chittenden, an army engineer discussed below, reported the discovery of a tree with the initials "J.O.R. Aug 28, 1819." There is some indication that the ititials were that of a trapper by the name of Roche. Additionally, some evidence of early trappping activities by trappers for the Hudson's Bay Company has been found. Daniel T. Potts, after whom the Potts Hot Spring Basin on the shore of West Thumb Bay is named, described discovery of thermal activities in the Park as a part of the Ashley expedition of 1822. Jedediah S. Smith visited the area in 1826. Other early visitors included Joseph L. Meek and Osborne Russell. In her 1870 biography of Meek, The River of the West, Frances Fuller Victor describes Meek's first view of Yellowstone:

Although, it is true that at one time thousand of years ago as discussed on the ensuing pages, brimstone emitted from craters even larger than described, Meek did not observe such eruptions of blue fire and brimstone. Meek, himself, as were many early mountainmen, was a larger than life figure. A mountain man working for the Sublette Brothers, he later emigrated to Oregon. There, on May 2, 1843, he inspired a crucial 50-52 vote whereby the residents of Oregon determined that what is now Oregon State and Washington State should be a part of the United States rather than a part of British North America. Regardless of the descriptions of the Yellowstone by early visitors, the creation of the Park as the first National Park in the world in 1872 was as a direct result of the Hayden Expedition and the paintings of Thomas Moran and photography of Wm. H. Jackson.

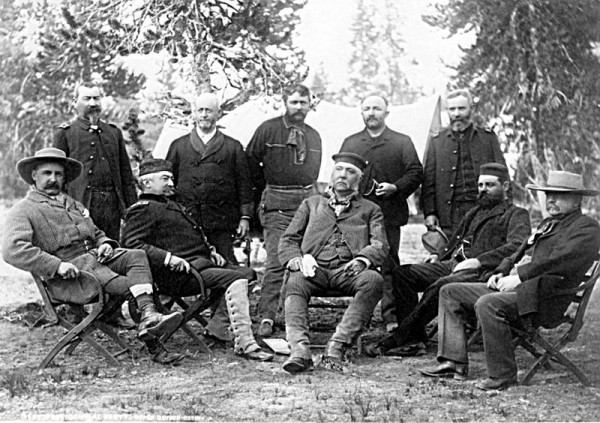

President Arthur's camp, 1883, Upper Geyser Basin. Illustration based on photo by F. Jay Haynes. As noted earlier the first president to visit the park was Chester A. Arthur. President Arthur was allegedly inspired to visit Yellowstone by a Bierstadt painting of the Yellowstone Falls which the artist had loaned the Executive Mansion in hopes that Congress would purchase the painting. The original is now on display in the Whitney Museum in Cody. The Arthur party proceeded by train to Green River City, from there they proceeded by Wagon to Fort Washakie. From there by horse back, followed by an escort of 75 cavalrymen, guided by Togwatee, the party crossed the pass of the same name into Jackson's Hole and northward into the Park. The presidential visit inspired a renewed interest in the Park. The President returned on the newly open Park branch line of the Northern Pacific which by that time had extended its lines to Cinnabar, Montana, now a ghost town a short distance northwest of Gardiner.

Members of President Arthur's party, 1883. Left to Right: Standing, Lt. Col. Michael Sheridan, Gen. Anson Stager, Capt. Philo Clark, Judge Daniel G. Rollins, Lt. Col. James F. Gregory; Seated, Montana Governor Schuyler Crosby, Lt. Gen. Phillip Sheridan, President Chester A. Arthur, Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, and United States Senator George Graham Vest. , "The Secretary of War, upon the request of the Secretary of Interior is authorized and directed to make the necessary details of troops to prevent trespassers or intruders from entering the park for the purpose of destroyng game or objects of curiosity therein, or for aany purpose prohibited by law, and to remove such persons from the park if found." Three years later when wholesale depredations in the park continued unabated as a result of the failure to fund protection of the park, the Secretary of the Interior invoked the provision. General Sheridan ordered units of the Army in to replace the previously politically appointed civilian superintendent and assistants. Senator Vest had previously served in the Confederate States House of Representatives and at the end of the War was a member of the Confederate Senate. At the time of his death in 1904, Vest was the last surviving member of that body. Senator Vest was most famed for two things in his career as a lawyer. In 1853, as a young lawyer, he was requested to defend a Negro slave, Sam who had been charged with the murder of Elizabeith Rains. Vest undertook the representation. Vest secured an acquittal. A mob outside was beseiged the courthouse and removed Sam. Sam was held for time suffcient for large crowds to gather for a promised execution. Sam was brought out and and chained and set upon a pile of kindling and wood. Some watched from nearby trees. Slave owners brought their slaves to witness the lynching as an object lesson. The pile was set alight until in the words of one witness he was burned to a crisp. The sheriff buried what remains there were upon the spot. The family of the owners of Sam were ordered by the mob out of the county. Vest was also told to leave. Vest's response was to stay and open his law practice there. Senator Vest's most famous trial, however, was a lawsuit for fifty dollars for the killing of a dog, "Old Drum." Old Drum had been shot by a neighbor. The defense ridiculed the idea that an old "Black and Tan" hunting dog was worth anything. That was the opening Vest needed. Vest told the jury:

The verdict in favor of the owner of the dog was sustained by the Missouri Supreme Court. See Burden v. Hornsby, 50 Mo. 238 (1872). See also State v. Stacy, 355 S. W. 2d 377 (St. Louis Ct. of App. 1962). Today, a monument on Big Creek, near where Old Drum fell, bears the simple message, "Killed, Old Drum, 1869." But if President Arthur was inspired to visit Yellowstone by Bierstadt's painting, British aristocracy were inspired by the 1874 visit by the Earl of Dunraven (1841-1926), documented by his 1876 account, The Great Divide: A narrative of Travels in the Upper Yellowstone in the Summer of 1874. The Earl was guided by Texas Jack Omohundro and accompanied by another noted world traveler, Dr. George Henry Kingsley (1827-1892), painter Valentine Walter Bromley (1848-1877), cook and barber Maxwell, and by his colley Tweed. The Earl was displeased by Bromley who devoted most of his efforts at documenting Crow Indians rather than the wonders of Yellowstone. Bromley provided the illustrations for Dunraven's book. But the earl's displeasure was illustrated by the faint, nay, non-existent mention of Bromley in the book. As a result, some have debated whether Bromley was actually included in the expedition to Yellowstone. In 1877, Bromley died of smallpox at the very time a show of his Indian paintings was opening.

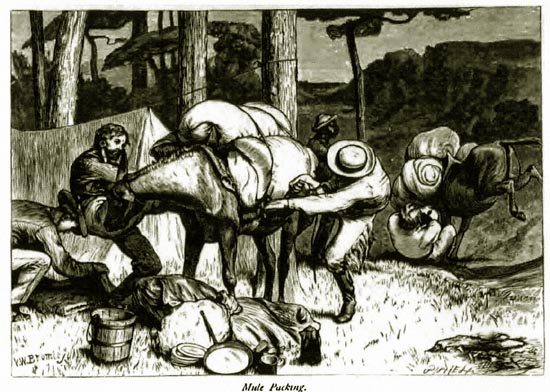

Dunraven's book, however, had significant effect on public perception of Yellowstone. Henry Gannett (1846-1914), later chief geographer for the United States Geological Survey, removed Philetus Norris' name from a peak in the Park and renamed it for Dunraven. Philetus Norris, the second superintendent of the park, in a moment of modesty had named it for himself. Gannett later explained, "This I have named Dunraven Peak in honor of the Earl of Dunraven, whose travels and writings have done so much toward making this region known to our cousins across the water." The Dunraven Trail is also named for the Earl. Today, getting to the Park is comparatively easy. It is less than a day from Cheyenne. Only a matter of an hour or two from Jackson. But in the the days of the Earl, one would allow several months. Merely getting to the Park in the early days was an adventure in itself. Dunraven proceeded by train from Denver to Ogden, thence to Corinne, Utah, and from there northward by chartered stagecoach to Virginia City. Originally, the Earl had planned going northward from Green River City via Camp Brown (present-day Lander) but had been warned not to by Gen.Sherman because the Indians had gotten restless. The Earl described the conveyance: [W]e piled ourselves and traps into a lumbering, heavy, old-fashioned stage-coach, and, under the guidance of a whisky bottle and an exceedingly comical driver, started for Virginia City. Jehu was a very odd man and wore a very odd head-dress, consisting of a chimney-pot hat elongated by some strange process into a cone, having the brim turned down and ventilated by large gashes cut in the sides. He was very garrulous, and, I grieve to add, profane.  Packing the Earl of Dunraven's mules for the trip to Yellowstone National Park, 1874. Drawing by Valentine Walter Bromley.

In some aspects, Dunraven was less than impressed by the park. Of the mud pots, now a favorite tourist point, the Earl noted that they, "fuss and fume and sputter and spit in such a rage about nothing, and with such small results, and are withal so dirty and undignified, that one feels quite inclined to laugh at them." Nor was the Earl overcome by the hotel amenities at Mammoth Hot Springs. The owner, James C. McCartney, advertised the structure as a "clubhouse" with a bar. It did have a bar, but the remaining facilities had been exaggerated. Guests were required to provide their own bedrolls and slept on the packed dirt floor. Dunraven in his review of the facilities noted that it was "the last outpost of civilisation,-- that is the last place where whisky is sold." He described it as a "little shanty which is dignified by the name of hotel." The hunting was not up to snuff. Dunraven wrote, "We had counted upon getting plenty of game, deer or elk, all through the trip and had arranged the commissariat accordingly. But we had grievously miscalculated either our own skill or the resources of the country for an atom of fresh meat had we tasted for days. Trout I had devoured until I was ashamed to look them in the face."

McCartney Hotel, Mammoth Hot Springs.

The Earl returned to the park two years later, again with Omohundro and Dr. Kingsley. The visit was ill-timed. It was at the same time as the visit by Chief Joseph on his flight to seek the protection of the Queen-Empress. A tourist was somewhat betaken by the costume of the earl's entourage passing through the park. The party consisted of one man driving a remuda of loose horses, followed by Texas Jack, "a tall powerfully built man, and as he rode carelessly along, with his rifle crossed in front of him, he is a picture. He was dressed in a complete suit of buckskin and wore a flaming red neckerchief, a broad sombrero, fastened up on one side with a large eagle feather, and a pair of beautifully beaded moccasins." Shortly thereafter, came the earl and Dr. Kingsley "both of whom were dressed in buckskins and wore large sombreroes." In 1872, Dr. Kingsley and Dunraven had been hunting together in Nebraska with Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack acting as guides. In an account of those adventures, Notes on Sport and Travel, London, 1900, Kingsley described Omohundro: If Buffalo Bill belongs to the school of Charles I., pale, large eyed, and dreamy, Jack, all life, and blood, and fire, blazing with suppressed poetry, is Elizabethan to the back-bone! He too is an eminently handsome man, and the sight of him in his fringed hunting buckskins, short hunting shirt decorated with patches of red and blue stained leather, pair of delicate white moccasins embroidered by the hand of some aesthetic and loving squaw, with his short, bright brown curls covered by a velvet cap with a broad gold band around it, would play the very mischief with many an eastern girl's heart.Dunraven noted that in Yellowstone, Omohundro was always smoking, except when he is eating, and the few minutes he is obliged to devote to mastication are grudgingly given—is holding forth to the rest of us, telling us some thrilling tale of cattle raids away down by the Rio Grande on the Mexican frontier; graphically describing some wild scurry with the Comanches on the plains of Texas; or making us laugh over some utterly absurd story narrated in that comical language and with that quaint dry humour which are peculiar to the American nation. Boteler is lying on his stomach, toasting on a willow-wand a final fragment of meat. He does not use tobacco, and eats all the time that others smoke. He is greatly relishing Jack's story, except when some not over-complimentary allusion to the Yankees comes in ; for Boteler served in the Federal Army during the great Civil War, while Jack, Virginian born and raised in Texas, naturally went in for the Southern side.Others in the earl's 1877 party included several British army officers and scout Boney Earnest.

The tall and thin Dunraven throughout his life impressed observers by always dressing the part. The Earl is reputed to have noted, "If you want to destroy an aristocracy, cut off their collars, not their heads." In later life after Dunraven twice competed for the America's Cup, he would affect a nautical appearance. Indeed, one would almost get the impression that for Victorian aristocrats, life was one continuous costume party. They loved costumes. In the United States, the love of costumes found its expression in the elaborate uniforms, robes and regalia of the various fraternal orders. One of the more famous outfits worn by Dunraven was at an 1897 costume ball at Devonshire House. The earl appeared as the wicked Cardinal Jules Mazarin, the de facto ruler of France during the minority of Louis XIV. Mazarin was rumored to have been secretly married to Louis XIV's mother. At the time of the ball, Mazarin had been brought back to prominence as a result of an Alexandre Dumas novel Twenty-years After, a sequel to The Three Musketeers. The ball was attended by the Prince and Princess of Wales (later Edward VII and Queen Alexandra) who appeared as the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitalers of Malta and Marguerite de Valois. The Prince's costume was described in the Echo as

Lady Randolph Churchill appeared as Theodora and the 8th Duke of Devonshire as the Emperor Charles V. The Earl is also closely associated with the Rocky Mountain National Park at Estes Park, Colorado. There he acquired over 9,000 acres of land and constructed a hotel. The acquisition of the land in Colorado was perhaps not entirely by legitimate means. Land was acquired by American citizens ostensibly for their own use. In actuality it was acquired on behalf of the Earl. The impact of the Earl's visit and his book on visitation to the Park should not be underestimated. President Roosevelt in his dedication of the Arch noted that more Europeans visited the Park than did Americans from the eastern states. Next Page, Yellowstone continued. |