|

|

|

About This Site |

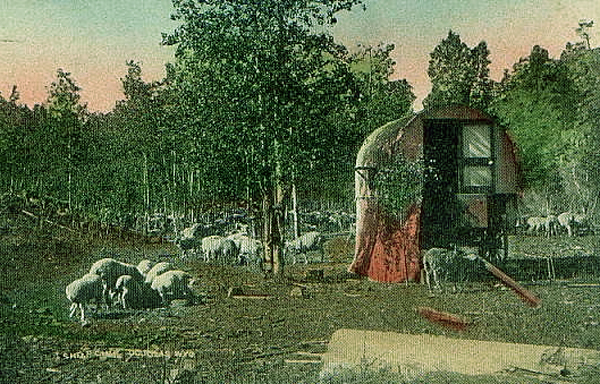

Sheepcamp near Douglas, cir. 1900

Although in the popular mind Wyoming is mostly associated with cattle, the cattle count having increased from 8,000 in 1870 to 1,500,000 in 1885, the impact of the "Great Die Off" discussed with regard to Cattle was an increased emphasis on a change from cattle to sheep. Even the Two Bar made the change. This is not to say, however, that sheep did not have an importance before 1886. The 1880 census reflected a sheep count of over 500,000 and by the mid 1880's there were some 106,000 sheep in Albany County alone. In contrast the 1870 census reflected only 6,409 sheep in the entire territory. The Warren Livestock Company, still in business, was founded by Francis E. Warren in 1874. In 1894 the Company had an inventory of 1,826 horses, 26 mules, 3,220 head of cattle and 63,433 sheep. In addition to Gov. Warren, other governors had an interest in sheep including Eugene Osborne, B. B. Brooks, and DeFprest Richards a stockholder in the Platted Valley Sheep Company which held some 37,000 sheep.. This is not to say that prior to the winters of 1886 and the winter of 1888-89, that Warren did not have an interest in cattle. Warren at one time had an interest in cattle in the Dakotas and with M. F. Post owned the Spur Ranch at LaBarge in the Green River Valley. Prior to the winter of 1888-89, the Spur Ranch had 15,000 head of cattle. That winter, as in the Winter of 1886, deep snow was followed by a thaw and then a freeze, creating a ice sheet through which the cattle could not graze. The following spring at round-up only 800 cattle were accounted for. Jim Mickelson, foreman of the Spur, noted the effect at his own homestead. He described his being able the following spring to step from frozen carcass to frozen carcass. Smaller ranchers suffered the same losses. Ed Steele lost all but 8 of his 87 head.  Along Nowood Creek, August, 1916

Note sheep wagon at right side of photo. Only 7 years before the above photo, on April 2, 1909, the last armed conflict between cattlemen and sheep growers occured in the Nowood Valley at Spring Creek, 7 miles southeast of Ten Sleep. In the "Spring Creek Raid," seven masked riders raided Joe Allemand's sheep camp, killing Allemand, his nephew Joe Lazier and Jules Emge and burning their two sheep wagons. The raid was supposedly motivated by Allemand's bringing his herd of 5,000 sheep into the Nowood Valley which cattle interests had declared off limits to sheep. (Writer's note: The usual rule is, "Fence sheep in, fence cattle out.") In November 1909, Herbert Brink, Tommy Dixon, Milton Alexander, George Henry Saban, and Ed Eaton, local cowboys, were brought to trial in Basin for participation in the killings.  Spring Creek Raid Defendands Top Row: Dixon,Brink, Eaton. Bottom: Alendander, Saban

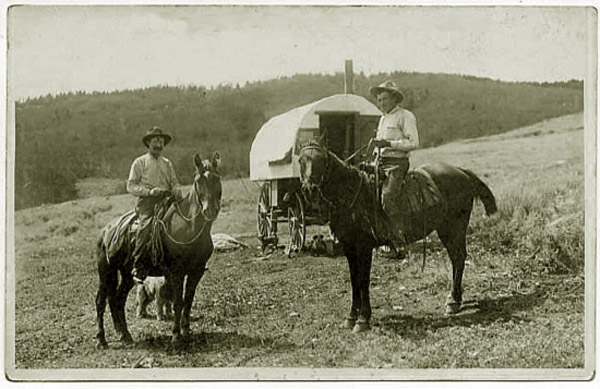

Two others, Charles Ferris and Albert Keyes turned state's evidence and were not charged. Brink was convicted of first degree murder. Alexander and Saban were convicted of second degree murder. Dixon and Eaton each plead guilty to arson. Eaton died in state custody. Saban escaped in 1913 and was never recaptured. Dixon was paroled in 1912. Brink and Alexander were paroled in 1914. The public reaction to the raid resulted in the ending of such violence on the open range. An historical monument now marks the site of the raid.  Sheepherder and his wagon, Campbell County, 1910

The Spring Creek raid was, however, not the only incident of such violence, it was merely the last.  A raid on a sheep camp, 1877.

"Sheep dead lines," such as that in the Nowood Valley, were proclaimed by other cattlemen. The Spur Ranch declared a dead line across the Little Colorado Desert from the mouth of Fontenelle Creek to Farson, north of which no sheep were permitted. In southwest Wyoming along the Green River a "sheep war" raged at the turn of the century. It will be recalled that the introduction of sheep into the Upper Chugwater may have resulted in the killing of Willie Nickell by Tom Horn.  Sheep Raid, 1902. The August 15, 1902 edition of Wool Markets and Sheep, p. 4, "The Sheep and Cattle War," reported on the sheep raids in Colorado and Wyoming. Near Farson, George Sedgwick's camps were raided. He lost some 65,000 sheep. In Colorado, Griff Edwards lost some 14,000 sheep. He moved to Oregon. In Rout County, Colorado, Geddes & Bennett of Cheyenne lost sheep. A lady who raised prize Angora goats on lands not used by cattle, had her herd of goats killed. Herds were dynomited, clubbed to death, driven off precipices in the mountains, or scattered to be devoured by mountain lions and wolves. Herders were shot. The following month the story was picked up by Leslie's Illustrated News.  Sheepherders, Muddy Mountain, Wyoming, undated.

Not even the giant Warren Livestock Company was imune from Sheep raiders. In August 1898, a warren Land and Cattle Company sheep camp in northern Colorado was raided, sheep were killed and the two sheepherders badly beaten. In Crook County, Silas A. Guthrie (1867-1938), of the Empire Sheep Company, along with other sheep growers received warnings that if they did not discontinue bringing in sheep they would face the consequences. One of Guthrie's sheepherders was shot and a wagon burned. Mary B. Guthrie recounted the story that her Grandmother Guthrie, as a precaution, would carry a pistol in her father's diaper bag. See Wyoming Lawyer, "From the Desk of the Executive Director," October 2005. In Upton, the sheep shearing pens were burned down. In the Green River valley in July, 1902, masked men killed 2,000 sheep and one sheepherder who crossed the "deadline."  Sheep Camp, 1921.

But why was there an antipathy to sheep? Zane Grey in The Last Man, the tale of a sheep war in Arizona, noted the cause, the total destruction of pasturage:  Sheepherders, 1904.

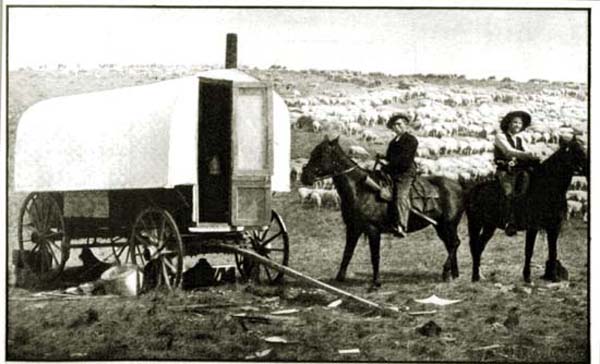

Professor Larson indicates that the tales of sheep wars were exaggerated. See Larson, 2nd Edition, revised, p. 372. Professor Larson wrote, "Men working on the range, however, were really in less danger than those who worked in the coal ines or on the Union Pacific railroad." But there is, perhap, and explanation for the paucity of reports from the front in the sheep wars. Henry F. Cope wrote:Cooperating with this natural antipathy and tending to perpetuate and intensify the long and terrific contest of the bench lands there is the fact of the conflicting interests of the sheep-owner and the cattle-owner. The man of beef not only hates the man of mutton, he fights him; and his fights have been with the weapons of flesh and blood, and not with those of warrants and wires, with warrants of lead rather than of paper. This conflict is an entirely different thing from a hard feeling or a difference of opinion between neighboring farmers, or between conflicting interests in agricultural communities, matters which may be fought out in a court of justice. The sheep men have been almost as anxious as the cattle men to keep their differences out of the courts, frequently because both were trespassers on the ground they were using. Doubtless this unanimity of purpose to keep out of the public eye accounts for the meager knowledge generally possessed of this warfare. Now and then one may read that "trouble is brewing, or has broken out again, between the sheep men and the cattle men on the Big Muddy," or "on the Sweetwater"; but just what the trouble is and how it is being brewed, or how it will be settled, is not told; the daily, having no facts, wisely refrains from furnishing them. 12-horse hitch, Nowood.Note the sheep wagon in the background. Sheepherding continued on next page.

|