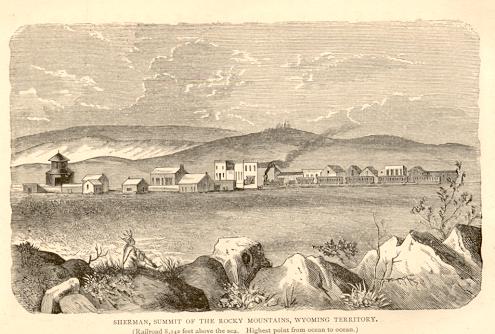

Sherman, Wyoming Terr., 1874, woodcut

Harper's Weekly,

based on photo by C. R. Savage. See Stereograph below.

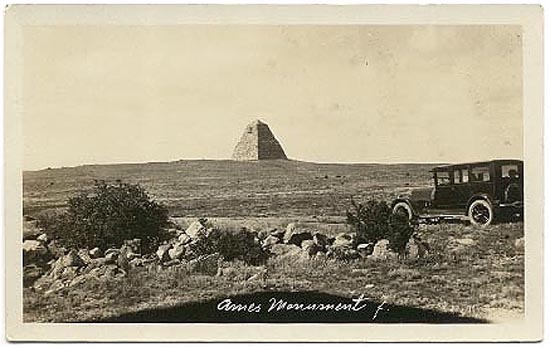

Sherman, Wyoming, was located a quarter mile from the

Ames Monument discussed on the Preceding Page .

Harper's Weekly frequently used photographs as the

basis for its illustrations. Sometimes the artist would enhance the picture, as in this instance with

the bushes and the train. Compare the

above wood cut with the stereograph by C. R. Savage immediately below.

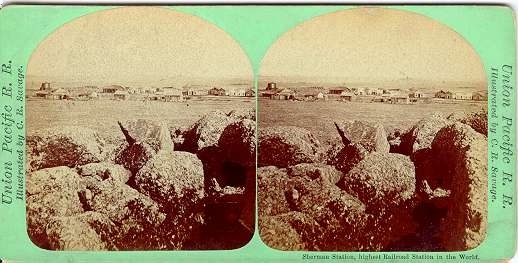

Sherman, approx. 1870, stereograph by C. R. Savage. See close-up on next page.

Ames Monument, Sherman, Wyo., photo by

Henning Svenson

For discussion of Henning

Svenson, see Laramie II.

The coming of the railroad had a drastic impact upon Wyoming. As the Railroad progressed across

the Territory small towns and cities sprang up

at the railhead to serve the

needs of the Railroad, the graders and others drawn to the area. Such was

Sherman, seventeen miles east of

Laramie and located at the highest point on the Railroad between the two coasts, 8,262 ft. above sea level.

Sherman was located in an area, at one-time known as "Lone Tree Pass" and later as

Evans Pass, named after James A. Evans (1830-1887), an English-born civil engineer who

discovered the Pass in 1864.

|

Who Discovered Evans Pass?

Controversy exists as to credit for "discovery" of the Pass.

Some writers, including Stephen Ambrose, based on Dodge's 1910 memoir How We Built the Union Pacific Railway, credit discovery of

the pass to General Dodge in September, 1865. Although, in a footnote, Ambrose concedes that Professor

Walter Farnham has described Dodge's claim as "fanciful." Evans ran a survey party in Wyoming during the

1864 "season" which proposed the "Lodge Pole Creek" route for the railroad. In a

March 1865 letter to Dr. Durant, Evans compared various routes through Wyoming including a route

along the Cache Le Poudre, one through Bridger's Pass, and one and through South Pass. Evans not only noted distances,

grades and cost of construction, but the presence of building materials, coal, and

future business for the railroad. Although it is apparent that at the time of

Evans' letter, a final decision had not been made between the Lodge Pole Creek route and the

Cache le Poudre Route, it is also clear that at least a tentative decision was to

be made momentarily. Consulting Engineer Silas Seymour in his 1867 grandiosely titled book,

Incidents of a Trip Through the Great Platte Valley, to the

Rocky Mountains and Laramie Plains, in the Fall of 1866, with a Synoptical Statement of the

Various Pacific Railroads, and an Account of the Great Union Pacific Railroad Excursion to

the One Hundredth Meridian of Longitude, notes that the route was surveyed by Evans in 1865 and seemingly

gives credit to Evans:

After following the travelled road to a point within about two miles of the Willow Spring

Station, we diverged to the left, in a more northerly direction, and

ascended the westerly slope of the Black Hills to a depression in their

summit, some miles north of Antelope Pass, and considerably to the south

of Cheyenne Pass, named Evans' Pass, in honor of the Engineer of that name,

who formed one of our party; and to whose energy, and skill in his

profession, the Railroad Company are indebted for most of the information

in their possession respecting the region over which we were travelling.

The actual "final-final" decision was not made until November 1866. It is clear that

a determination had been made by early 1865, before Dodge's "discovery", that a route near

present day Cheyenne was feasible. No such decision would have been

made unless there was also a determination as to how the Black Hills, now known as the Laramie

Mountains, could be crossed. Of course, there are indications that the preliminary decision was a

route north of present day Cheyenne through Cheyenne Pass following the old

Lodgepole Trail. The Lodgepole Trail was about 12 miles north of present day Cheyenne and

passed near present day Federal south of Horse Creek. Indeed, in 1865,

Evans surveyed an "experimental" route through Cheyenne Pass and calculations of

grades, etc. were made. Evans also laid out an experimental route through what was to become

Evans Pass. Both Jesse L. Williams, an engineer and a government director of the

railroad who accompanied Seymour on his inspection tour, and Seymour give Evans credit for having

surveyed Evans Pass.

The only question left by the end of 1865 was whether

the route would be via present day Cheyenne or via a route basically following the

old Cherokee Trail. The final decision took into account the very factors discussed by

Evans in his March 1865 letter, grades, building materials, and coal, and yet be

as close to Denver as practicable. Dodge, as to his accomplishments, is one not known for

undue modesty. Thus, Professor Larson has noted that Dodge over the years gave

different versions of the discovery. Ambrose takes Dodge's history of the

building of the railroad as striking Ambrose "as true." Farnham, "Grenville Dodge and

the Union Pacific: A study of Historical Legends," Journal of American History, March

1965, tends not to believe

Dodge in many details. Professor Larson accepts Dodge's claim but with a grain of

salt, and notes that Dodge exaggerated his involvement in the actual construction of

the railroad. Larson continues:

"Farnham has stripped [Dodge's] discovery of its romantic embroidery by directing attention

to Dodge's diary, in which there is no mention of Indians but only of 'Indian signs' on the day

the gangplank was found." Larson, History of Wyoming, p. 39-40. (Dodge claimed that the

discovery was made after an encounter with and subsequent escape from a large party of Indians).

For description of the "Gangplank" see

discussion under Lincoln Highway. Edwin L. Sabin, Building the Pacific Railway: The construction story of American's Firt Iron

Thoroughfare, J. B. Lippincutt company, 1919, takes the position that Dodge

discovered the pass, lost it, and sent Evans out to rediscover it.

It should be noted that the pass was known as

"Evans Pass" as early as 1866 during Seymour's tour of the Black Hills with Evans, Dodge, and Williams. Dodge made his

claim of discovery in 1910, 45 years after the event when Dodge's memory may have been suffering

from the frailties of age, and 23 years after

Evans went to his grave and, thus, could not refute any of

Dodge's claims. The definitive answer, however appears in the testimony of Cornelius Scranton Bushnell (1829-1896), one

of the incorporators of the railroad, before the Select Committee of the House

of Representatives in relation to the affairs of the Union Pacific Railroad Company, Jan. 15, 1873. Mr.

Bushnell unequivocally gives credit to Evans. Bushnell was a highly respected entrepreneur whose investment

in the USS Monitor saved the United States Navy from the onslaughts of the CSS Virginia. The possibility exists, of course, that Dodge "discovered" the pass and Evans surveyed it.

With, however, all due respect to Professor Larson, it appears likely, based on contemporeous reports,

credit for the discovery is due James A. Evans, with the actual route through the pass being

selected by Seymour based on his inspection tour.

|

Albert D. Richardson, a correspondent for the

New York Tribune wrote of Sherman in "Through to the Pacific," 1869:

Sherman is the highest railway point in the world -- eight thousand two hundred and forty feet

above the sea. Still, it is not the backbone of the Rocky Mountains, but only of the

Black Hills, an outlying eastern range. The continental divide is two hundred miles

further west and one thousand feet lower. Sherman is in Evan's Pass, which bears the

name of its discoverer. He was one of many martys to this great work -- a

Union Pacific surveyor, killed by the Indians. The pass is in no sense a

gorge or canyon -- but looks, topographically, like a vast rolling

prairie disfigured by rocks and reached by a gentle ascent. Nor are

the distant mountains on the north and south such slender peaks and pyramids as

fanciful artists depict, but only low, irregular, broken ridges.

The description of the topography is accurate. The death of Evans at the

hands of the Indians was, however, premature. Little has been written of

Evans, after whom Evanston, Wyoming is named. In Stephen Ambrose's history of the construction of the

Pacific Railroad, Nothing Like it in the World, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2000, Evans arrives

upon the scene in 1864 with his employment by then Chief Engineer, Peter Anthony Dey. Dey

resigned as Chief Engineer at the end of 1864 in a dispute with Consulting Engineer Silas

Seymour and Dr. Durant over apparent efforts to pad the cost of the railroad construction. Evans

disappears from Ambrose's book with an 1868 telegram from Durant to Evans: "Notify Casement

that 16,000 feet of track per day won't do," and an observation several pages later that Evanston was named

after Evans.

It has been said that the most enduring relics of those who have gone before will be found in

names. It is thus in Cheyenne. In the streets of the downtown area are found the names of the

early engineers of and officials of the railroad officials who built the Union Pacific: Evans Ave. (James A. Evans, Division

Engineer), Seymour Ave. (Silas Seymour, Consulting Engineer), Maxwell Ave. (James Riddle Maxwell, civil engineer),

Peter A. Dey (Chief Engineer), Reed Ave. (Samuel B. Reed, Division Engineer), Dillon Ave. (Sidney Dillon, Director), Bent Ave.

(Luther S. Bent, contractor).

At Table, L to R: Consulting Engineer, Silas

Seymour; Railroad Director, Sidney Dillon; Railroad Vice President, Thomas Durant;

Railroad Director, John Duff.

Disputes between the engineers in the field and Seymour were not uncommon. Seymour had made his

fame by having his route selected for the New York and Erie Railroad over two

competing proposed routes. Thereafter, he served as the New York State Engineer having

responsibilities for mapping of Upstate New York and with regard to the

State-owned Erie Canal. For a short period of time he also served as the

Engineer for the Kansas and Pacific. Most of the railroad engineers of the day

preferred stone or iron bridges. Seymour preferred cheaper wooden "Howe Truss" bridges. One

source even indicates that Seymour wanted to use longitudinal wooden timbers under the

rails in lieu of crossties. Among the wooden bridges designed by Seymour was the

terrifying Dale Creek Bridge which would sway in the wind (photos and discussion on

subsequent page). The bridge was replaced after only

eight years. It will be recalled all of the wooden bridges on the

Union Pacific ultimately had to be replaced, leading in part to the railroad's

financial difficulties in the 1880's.

Participants at Meeting at Fort Sanders, July

1868

Left to Right: Sidney Dillon: Gen. P. H. Sheridan: Mrs. Joseph H. Potter:

Gen. John Gibbon; Mrs. John Gibbon; 13 year-old John Gibbon, Jr.; Gen. U. S. Grant (with hands on fence),

Col. (Bvt. Brig. Gen.) Frederick T. Dent, military secretary to Gen. Grant;

unidentified woman and young ladies; Gen. Wm. T. Sherman (sitting on stile); unidentified woman and

children; unidentified; Mrs. John W. Bubb;

Capt. Mail; Mrs. Lincoln Kilbourn; Brig. Gen. Adam Jacoby Slammer; Gen. W. S. Harney (with white beard and cape),

Dr. Thomas Durant (with hands clasped); unidentified; Lt. John S. Bishop; Col. (Brig. Gen. Volunteers) Lewis Cass Hunt; Brig. Gen Adam Kautz;

Lt. Col. (Bvt. Brig. Gen.) Joseph H. Potter, commander Ft. Sanders.

In July 1868, a showdown occurred at Ft. Sanders between Gen. Dodge and Durant, over

engineering of the Railroad. Things had begun to boil before the meeting in a dispute between

Seymour and Dodge over the proposed route of the railroad. The dispute is somewhat

reminiscent of the dispute that led to Dey's resignation and a concern expressed in

Evans' 1865 letter to Durant. In the letter, Evans notes that he had previously written Dr. Durant and

entrusted the letter to Seymour, but thought that Durant may have not received it.

Evans wrote Dodge at the time of the showdown offering his resignation should Dodge be removed. At the meeting at

Ft. Sanders, Gen. Grant, even though he had not yet gone through the formality of being

elected President, made it clear that the government expected Gen. Dodge to be the engineer. Following

the completion of the Railroad, Dodge became the president of the Texas and

Pacific. Evans was chief engineer of the Western Division (never actually built), living in San Diego. Later Evans was chief engineer for the

Denver, South Park, and Pacific, living in Denver, with wife Jessie, brother John A. Evans, also

a civil engineer, and child.

Next Page, Sherman continued.

|