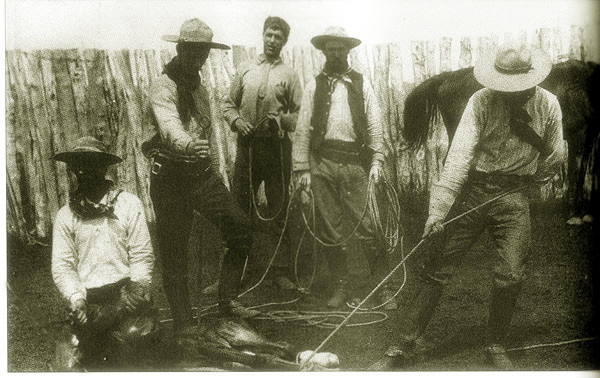

The "76" ("Frewen Castle"),

Powder River Cattle Co., circa 1885

One of the first and largest cattle companies on the Northern Great Plains was the "76" on Powder River

established by the Richard and Moreton Frewen. The Frewens were the two younger sons of Anglo-Irish landed gentry.

Moreton born in Sussex but much time was spent in Ireland. He was educated at Eaton and Cambridge.

The ranch was established following a

visit by the two brothers to John Adair and Charles Goodnight's "J A" in the Texas Panhandle.

From there, pausing at Estes Park to visit the Earl of Dunraven, they proceeded northward into Wyoming.

Moreton was impressed by the size of Wyoming buffalo herds which were much larger

than those on the "J A."

"Buffalo Hunting by Red Indians in Wyoming," illustration from Moreton Frewen's

autobiography "Melton Mowbray: And Other Memories," Publisher, H. Jenkins limited, 1924.

[Writer's notes: The illustration is the same as two oil paintings entitled "Last of the Buffalo" by Albert Bierstadt, one displayed at the Whitney Gallery of the Buffalo Bill

Museum in Cody and the other in the Corcoran Gallery of the National Gallery, Washington, D. C.]

About twenty miles from the "Castle," the Frewens occupied the former camp at Powder River Crossing which served as the local business end of the ranch.

There the cowboys stayed so as to not disturb the guests as the castle. The Frewens maintained a store at the crossing.

In 1880, Major Lewis Lovatt Ayshford Wise (1844-1927), late of the 8th King's regiment, on a hunting trip to the Big Horns stayed at the Frewen's Store on August 30, 1880, and left a description:

"This is a deserted Fort....The log huts, built in a large square, are still

standing. Frewen's store is in one of them, and there are two or three

bedrooms there, rather rough and ready, one of which I secured....I was

very tired towards night, and turned in early-no sheets-only a pair

of blankets to get between, but I was soon asleep notwithstanding." 12 Annals of Wyoming,

"Diary of Major Wise/i>, April 1940, p 85-118

The Annals' account was accompanied by footnotes by Howard Lett of Buffalo,

"the stage station was eventually made up of a large, long building

(store, saloon, and living quarters in one) along with stables,

a blacksmith shop, and numerous old dugout cabins." Additional "amenities" were provided including

fresh horses, tobacco, whiskey, and nymphs du pave.

From 1882 to 1891, William P. Hathaway ran the store and saloon which was

located directly east of the dry gulch at the end of the little patch of

timber.

Powder River Crossing.

Following University (Cambridge), Moreton spent his time having a riotously good time shooting grouse, the betting on the steeple chase at Doncester, at Newmarket, fishing in Ireland, the fox chases at Melton Mowbray, the

"season" in London and finishing with the Royal Ascot. .

Moreton augmented his rapidly diminishing income with gambling, but the cards had not favoured him.

In 1878, he found himself

at Donchester on Cup Day. There were only two runners, Pageant owned by Mr. Frederic Gretton and Lord Ellesmere's Hampton. The two jockeys

were England's most famous. Moreton explained:

Tom Cannon rode Pageant and Fred Archer the other. Archer always told me

what he knew, and in response to my query he said, "If you have had a good meeting and are playing with winnings I think you should back Hampton. But he has eleven pounds the worst of the weights and there's

not much in it."

I had a lot of the summer's loot in hand, enought to have bought a good stable of hunters. I had to lay a shade of odds on Hampton, and I went off and laid the whole lot.

The dear, handsome little horse ran most gamely, but in the last hundred yards tired under the weight and just failed to get home. * * * *

I went to the weighing room, shook Archer's hand, and I look and indeed felt so happy he never dramed I was a

heavy loser by the pretty race.

As discussed below, The Frewen Brothers'

ranch was at least for Moreton Frewen a looming financial disaster. The disaster was anticipated to be ameliorated somewhat

by his marriage in 1881 in New York to Clara Jerome, a daughter of American milionaire Leonard Jerome. Jerome's personal residence was a modest

little house on the corner Madison Ave. and 26th Street in New York. There the Jerome family had to make do

with a 600 seat home theatre on the second floor. The breakfast nook could seat seventy. Jerome had made and lost several fortunes

skating on the thin

ice surrounding possible bankruptcy and the thick ice of great wealth. Unfortunately for Moreton Frewen, the financial benefit derived from the Jerome

marriage proved to be disappointing. Jerome had managed to marry his daughter Jennie off to Lord Randolph

Churchill. The marrage secured Lord Randolph's father's blessing only, in the words of Olivia E. Coolidge, "Winston Chrchill and the

Story of Two World Wars" Houghton Mifflin, p 196, when Jerome "beggared" himself to raise the required dowry. The dowry was reputedly £50,000 together with a

£1,000 annual stipend. Another sister, Leonie, was married to the Second Baronet Leslie, Sir John Leslie (1857-1944). Thus, Moreton was well connected socially

but not well off financially.

Left to right: Lady Randolph (Jennie) Churchill, Mrs. Moreton (Clara> Frewen,

Lady John (Leonie) Leslie.

Clara Frewen spent one season at the ranch. She had a difficult pregnancy and lost the child followg a

jolting ride to the hospital in Cheyenne.

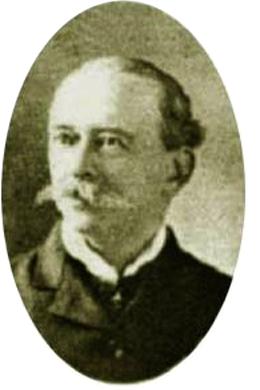

Moreton Frewen, approx. 1880.

Moreton Frewen was one of those who left Wyoming following the die off.

Moreton Frewen (1853-1924) was an uncle of Sir Winston Churchill. Reportedly, Frewen arrived in Wyoming with £16,000 and departed owing

£30,000. The £16,000 had been borrowed from Moreton's brothers Richard, Edward, and Stephen. In actuality the amount owed

was considerably greater. The Wyoming Tribune, Sept. 19, 1890, p. 2, and the National Live Stock Journal both

reported that Moreton may have owed the Cheyenne banking house of Morton E. Post & Company as

much as $100,000 personally. The extent of the losses may be indicated by the estimate that

in the year 1884, £100 was equivalent in purchasing power to £11,688.12 in 2017.

Shortly after the "76" was organized, Richard Frewen read the tea leaves as to the future of the ranch as managed by Moreton.

In October 1879, Richard wrote brother Edward complaining of Moreton's love of gambling. He noted that they had paid

$75,000 for 5,000 head. On inspection, there were only 2,700. As discussed later, see

Chugwater, others blamed the seller for running the cattle passed

Frewen twice. Forty-five years later, Moreton in his autobiogrphy "Melton Mowbray," admitted that he had purchased the

the cattle based on "book count." He had multplied the estimated average number of new calves for each of the previous two or

three years by five to arrive at the number of head of cattle.

John Clay in his autobiography, "My Life on the Range," p. 49 observed:

When I look back on those days and think how little we knew of the cattle business, even the men who were engaged in the industry, it is astonishing that more mistakes

were not made. One lesson I had learned and got it off by heart.

It was the bubble of book count. It was a gamble in which the dealer

always won. You can sometimes win at faro, often rake in shekels at

Monte Carlo, speculate on the Stock Exchange, bet on a horse race and

get your money back and more but a book count deal in cattle has always

proved disastrous.

Moreton and Richard parted ways. In 1883, Richard sold his interest to Moreton and organized his own

Dakota Stock and Grazing Co. on Chadron Creek, Nebraska.

Richard in an 1885 letter to Edward Frewen

noted: “Things West are very bad, Cheyenne is worse than dead, and the cattle business in the greater part of Wyoming is doomed * * * .”

Since Moreton was

broke, to raise the money for

the purchase from Richard, Moreton reorganized the "76" as

a joint stock company, "Powder River Cattle Company, Limited" He thereby raised £300,000.

To sweeten the pot for investors, Moreton agreed to take no salary as manager.

He would be compensated by a share of profits

after preferred shareholders received their

cut.

The estimates given to shareholders as to profits were based on estimated future book counts determined by Moreton's guesstimates as to the

fecundity of the cows, from which a guess was made as to losses based on the coming winters. The total number of calves

would be multiplied by reading the stars as to the future prices and expenses. The total numbers of head of cattle which determined the value of the

ranch was a multiple of the calves. See "A report to the Shareholders of Powder River Cattle Co., Limited" by Moreton Frewen, 1884.

On each of the factors used Frewen was way off. He overestimated the

the fecundity of the cows. His confidence in "book count" was such that after the "Great Die Off", when the carcasses of cattle were lying in the gulches and up the draws,

he was still counting them until finally the gentle winds of Spring brought forth an aroma that the book count might be off.

He was hopelessly optimistic as to the weather. From Moreton's descrptions, one would almost think Powder River Valley was

a subtropical paradise. Frewen underestimated the losses. Prices dropped. Ranchmen held on to the cattle in hopes the

prices would go up the following year. This led to overgrazing. An additional factor which may have led to

overgrazing was the increase in the number of cattle companies using open range. When the "76" was organized it was the only

ranch along Powder River. The 1884 Brand Book for the WSGA listed at least twenty-five cattle companies showing

Powder River as a usual range.

Branding on the "76," undated.

The new pot of money from the sale of stock enabled Moreton to continue his prolifigate ways. From the money raised, Moreton kept $60,000 for himself and took

$200,000 in common shares. As we will later learn below, the common shares were worthless. In 1881, Frewen had borrowed $100,000 from Morton E. Post & Co. in

Cheyenne. It still remained unpaid when the bank failed in 1887. In other words, Frewen was insolvent. In "Melton Mowbray," the only fault he put on himself,

was sending a panicky letter to the shareholders. They were according to Frewen, "amateurs," and should have in

their actions known better (They fired him). Acccording to Moreton, others were to blame. Most of all, the fault was that of Horace Plunkett. Plunkett was employed by the

Directors to liquidate the company in face of its overwhelming debt The overgrazing was President Cleveland's fault.

The image that Frewen projected to others was

similar to that recounted in the music hall song, "The Man Who Broke the Bank at

Monte Carlo," the background music for this page. In the song, the subject strolled down

the Bois de Boulogne. As he passed by, he put on such a grand appearance that the girls who saw him declared,

"He must be a Millionaire." In the song,

the subject had lost everything at Monte Carlo. In Moreton Frewen's case he too was always broke, but

he put on the appearance of being a millionaire. In reality it was likely that he could hardly

rub two tanners (six pence coins) together. Nevertheless, because of his projected persona, foolhardy Investors and American politicians flocked

to invest with him just as years later investors flocked to Bernie Madoff. Soon

like "Downton Abbey's fictional Lord Grantham's investment in the Grand Trunk Railway

their investment was gone.

It may be speculated that the construction of

the "castle" was designed for entertaining the rich and famous and thus enabled sales of further shares of stock, particularly in

light of large dividends most probably paid out of capital. Oscar Flagg, in his "A Review of the Cattle

Busines in Johnson County, Wyomng since 1882 and the Causes that led to the Recent Invasion," (1892) Electronc Texts in

American Studies, wrote that at the first annual meeting of the "76" a dividend of 35% was declared, p. 9. In 1884 Moreton reported to the

shareholders that after an "unfavourable year," money was available for a 27% dividend.

Frewen convinced others, including Lords Dunraven and

Londsdale, to invest in cattle. In addition to the "Castle," Frewen constructed in Cheyenne a house, still in existence, at 506 East 23rd Street, Cheyenne.

House at 506 East 23rd Street, Cheyenne, approx. 1974. The house was actualy used by Frewen for approximately one month a year.

The house has been somewhat modified from its original exterior form. To the left of the door, there was a bow window matching that on the right.

The porch was modified by being enclosed

The exterior of the house was originally brick but has been stuccoed over and the sun porch has been enclosed.

In essence in capitalizing the cattle company, Frewen followed the same path as

George Hudson, the British "Railway King" twenty years before. Hudson

financed his railways through a Ponzi scheme, in which outsized dividends were distributed to old investors from the capital

contributed by new investors. After the collapse of Hudson's railways, he lived out his life in obscurity.

Frewen lived out his life

with other schemes which invariably fell apart. Frewen's

later reputation was solidly built upon a foundation of spectacular financial

debacles earning him forever the titles "Mortal Ruin," the

"Sublime Failure" and the "Splendid Pauper."

In Victorian and Edwardian England, it was generally the obligation of the landed gentry such as the Frewens to leave their children

reasonably well-off and provide them a decent English liberal arts education which would enable the

student to do just about anything in later life.

Younger sons, such as Moreton, were expected, however, to go into the military, law, or the

ministry until they found themselves. Frewen's nephew,

Winston Churchill, son of Lady and Lord Randolph Churchill, went into the military before finding himself as a journalist and politician. Frewen's older

brother Richard for a brief period also went into the military but resigned his commission in 1873. It probably was expected that Frewen would go into the law.

Following Cambridge Moreton studied at the

Inner Temple. Certainly his father Thomas Frewen had left Moreton enough so that he could be comfortable without a great deal of

labor. Among other things, Moreton inherited upon his father's death 2709 acres at Connnera, Ireland. Later the property was

conveyed to a nephew Layton Frewen. At University, wasteful spending in riding to hounds and other sports at Melton Mowbray led to Moreton's inheritance being

squandered. Caspar Whitney, world traveller, news correspondent, big game hunter, editor of Outing Magazine, and full-time advocate of

amateur sports, wrote:

Melton-Mowbray, known as the "hunting metropolis" of England, which might with equal truth be called the hunting centre of the world,

is in Leicestershire, one hundred miles from London. Within a radius of

about twenty miles are the kennels of the Quorn, Pytchley, Belvoir,

Cottesmore, four of the greatest packs in England, and these,

together with Mr. Fernies', furnish hunting for every day of the week,

Sunday excepted, from beginning to ending of the season. But Melton-Mowbray

is a little world of itself, and a very fashionable one at that, and

you must not go there unless you have a long purse and a superlative

hunter * * * *Whitney, Caspar W: " Sporting Pilgrimage: Riding to Hounds, Golf, Rowing

Harper, 1894, p. 4.

Whitmey was an expert on such matters. He filed for bankruptcy in 1910.

Hunting Party at Melton Mowbray, Moreton Frewen standing upper right;

font row: Lord Granville Gordon, Miss Clarisa Manners, Mrs. Langtry, John "Hoppy," the 3rd Lord Manners.

Lord Manners supposedly earned his nickname "Hoppy" at Eton

from the manner of his gait. Lord Manners made one pilgimage

to Wyoming and the "76." The Army and Navy Journal, Sept. 17, 1881,

described Hoppy's arrival at the ranch:

Big Horn range of Mountains in Wyoming will become as well known

in England in the course of a few years as the jungles of India. Every summer increases -the number of the English gentry visiting this famous hunting-ground. We felt a little sorry for the last one of these noble scions who passed throughFetterman for the Powder River country—Lord Manners. He is quite a young man and very ingenuous, and being unfamiliar With the country he was easily taken advantage of by every cow-boy he met. Some one—I don't know who—induced him to buy a Broucho at Rock Creek, and instead of driving comfortably in a stage to Fort Fettermau, persuaded him that it was the correct thing to ride the pony, which he did, making forty-three miles in one day and forty miles the next on

"bucking" pony with an English saddle and short stirrups. The

young lord seemed quite used up when he reached Fetterman; but

notwithstanding, he started off’ the next day, all alone, for a

fifty-mile ride towards the Big Horn, and the last seen of him was

about ten miles north of Fetterrnan, his roll of blankets suspended

from the crupper of his saddle and nearly reaching'the ground on one

side, while his overcoat was thrown across the pommel and

dragging in the road on the other side; and my lord, utterly

oblivious to his surroundings, was bobbing up and down on his bucking

nag, with his neck outstretched, peering across the sand-hills eagerly

looking for the next stopping place. Lord Manners is an officer of the

Grenadier Guards, now stationed at Windsor Castle, and his leave

of absence expires on the 25th of October; hence his hurry.

Lord Granville was a famed sportsman who in the process of hunting all over the world managed to go broke. He lowered himself into becoming a

bookmaker. It has been long rumored that Mrs. Langtry maintained a friendship with Prince Edward, later

Edward VII and also with Moreton Frewen. At least she was seen riding a horse in the

a park which had been a gift from Moreton.

The "76," was located

about twenty miles upstream from present-day Sussex, Wyoming. Although Moreton Frewen was born in Sussex, England, Sussex, Wyoming,was allegedly named

by Mrs. H. W. Davis for Sussex County, Deleware. See Urbankek, Mae: "Wyoming Place Names," Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula (reprint)1988, p. 197.

Henry Winter Davis (1857-1923) came to Johnson County in 1887. After the winter 1886 he earned the nickname

"Hard Winter" Davis.] The "Castle" which, among other things, boasted a

solid walnut staircase, [The walnut was imported from Britain] and a thirty by forty foot dining room with a balcony at one end upon which musicians played.

The house included a piano brought from Chicago. According to

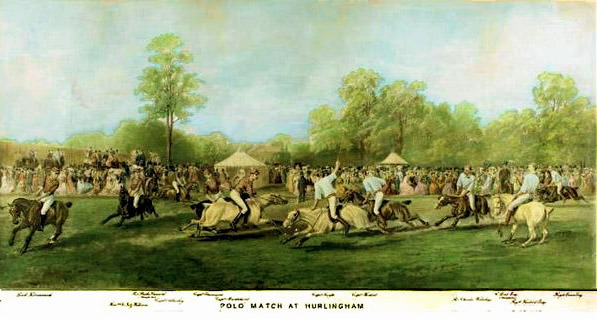

Horace B. Laffaye: "Polo in Britain: A History," McFarland & Company, Jefferson,N.C. 2012, p. 7,

there was even a short lived polo pitch. Some of the guests, including Charles Fitzwilliam, John Brooklehurt, and Sir Charles Michael

Wolseley, had made a name for themselves in Polo. Above the piano was a chromo-lythograph from George Earl's painting of a polo match

at Hurlingham between the Royal Horse Guards and the Monmouthshire team, played on 7 July 1878.

Chromolythograph, A polo match at Hurlingham beween the Royal Horse Guards and the Monmouthshire team, played on 7 July 1878, from George Earl

Also short-lived was a flag pole upon which flapped in the breeze the Union Jack.

On a Fourth of July, a celebratory dinner was served outside below the

flag. Several cowboys shot at the banner. Others joined in. The shots brought down that part of the

pole upon which the flag was fastened. It fluttered to the ground where it was trampled by the horses.

Sir Samuel Baker added to the description of the ranch:

Castle Frewen, as the superior log building was facetiously called by the Americans,

was 212 miles from Rock Creek station, and we were well pleased upon arrival to accept

their thoroughly appreciated hospitality. Their house had an upper floor, and a

staircase rising from a hall, the walls of which were boarded, but were ornamented with

heads and horns of a variety of wild animals; these were in excellent harmony with the

style of the surroundings. Here we had the additional advantage of a kind and most charming

hostess in Mrs. Moreton Frewen, in whose society it seemed impossible to believe that

we were so remote from what the world calls civilisation. There was a private telephone,

22 miles in length, to the station at Powder River, and the springing of the alarm every

quarter of an hour throughout the day was a sufficient proof of the attention necessary to

conduct the affairs successfully at that distance from the place of business.

There were howvever warnings that not all was to be successful. Some of the cowboys alerted

Sir Samual to that which he observed with his own eyes, but to which Moreton was oblivious: the range was being over grazed

and soon would turn to weeds, leading to disaster. Two years later the cowboys' prediction became obvious to even

Moreton Frewen. Rather than accepting blame, Frewen assigned the ruination of the ranch to Horace Plunkett (see below) and

to Grover Cleveland.

Clara Frewen, stayed only one season in the wilds of Powder River before returning to New York and

London.

Moreton Frewen Moreton Frewen

At the mansion, Frewen entertained the rich and

famous of the Empire with lavish hunting parties. Some of whom, at least, could best be described by the

Australian term "Pom" or "Pommy," so-called from the name of a tropical fruit. One visitor was the

Marquis of Queensberry, referred to by Oscar Wilde as the "Scarlet Marquis." Wilde apparently did not

care for the Marquis, describing him as "drunken, declasse and half-witted," and had, according to Wilde,

a stableman's gait and dress, bowed legs, twitching hands, a hanging lower lip and a bestial grin.

Another visitor, later famed as a diplomat,

Sir Maurice de Bunsen, sucessfully stalked and killed the ranch's only milch cow, thinking it to be

a skinny bison.

Among those entertained was the Seventh Earl of Mayo, Dermot

Robert Wyndham Bourke. The Seventh Earl's father had served as Vice-Roy of India but was assassinated at

Port Blair by a madman just as the band was striking up Rule, Brittannia. As indicated, also visiting the ranch

were Sir Samuel and Lady Baker. Although Sir Samuel was a noted world explorer, the Queen avoided receiving him due, in part,

to the unconventional courtship of Sir Samuel and Lady Baker. Sir Samuel purchased the future

Lady Baker at a bazaar in Bulgaria. Addtionally, Sir Samuel's reception in Victorian society was not

helped when Sir Samuel's brother Valentine was accused of committing an indecent assault upon a

woman in a railway carriage. Another who made the 250 miles trip north from Rock Creek, was the Fifth

Earl of Donoughmore. During the Boer War, the Earl with other Irish lords raised two companies derisively known

as the "Irish Hunt Contingent." The contingent's adventures, in the words of Thomas Pakenham, raised

a "ripple of mirth" in the Empire. It was problably not funny to Lord Roberts. Twenty thousand troops had to

be diverted in a vain attempt to effectate the contingent's rescue.

One hunting expedition in 1884 was spoiled by the death of Member of Parliament, the Honorable

Gilbert H. C. "Gilly" Leigh, the eldest son of the William Henry Leigh, the Second Baron Leigh (Second Creation).

For the circumstances of Leigh's death see Ten Sleep.

The Leighs were famous cricketeers who spared no expense on the game. The First Baron Leigh had played cricket

with Lord Byron in the first Harrow-Eton match. The First Baron's younger son, Gilbert's uncle,

played for Harrow, Oxford, Gentlemen of Warwichshire and I Zingali. Thus, it should not have been a surprise, when

Gilbert turned twenty-one, the birthday celebration took a week and included illuminations, fireworks, and

feasting. The centerpiece of the celebration was a two-day cricket match between the

Gentlemen of Warwichshire and I Zingali, the most exclusive and socially correct wandering cricket club in all of the

Empire.

Gilbert and his uncle played for I Zingali and his brother played for

the Gentlemen. the match ended when Gilbert, the last man out, scored a duck (in American

terminology, a "goose egg"). I Zingali had few rules. The annual subscription was not

permitted to exceed the entrance fee. There was no entrance fee. Membership was limited to 50. In 1845, one of the

members was designated as the Perpetual President. Since the presidency was

perpetual, no president has been elected since. The team colors were

red, black, and gold. Wearing of ties with the team colors, however, was regarded as gauche, it simply was not done.

The death of Gilly Leigh was not the first time that reported deaths caused concern on for the hunting parties on

Powder River. On August 20, 1879 The New York Times reported that the Honorable James Boothby Burke Roche, second son

of Baron Fermoy of Ireland, had been

killed. The Times report was greatly and prematurely exaggerated. Later Roche became the Third Baron and finally

died in 1920. Two of Roche's brothers,

Alexis Charles Burke Roche (1853-1914) and Edmund Burke Roche (1856-1919) also worked at the

ranch. Indeed Alexis ran the place for a while causing so much dissension amongst the cowboys that

Horace Plunkett, Frewen's partner, feared that he would have to work the ranch himself. After Alexis returned to

Ireland, he created an equal stir there. He sold a horse to Sir Timothy O'Brien. The horse was proved to be a broken-winded nag.

Roche refused to take the horse back. At the Dunhallow Hunt, Sir Timothy confronted Roche, "You are a liar and a cheat and a swindler; you have lived by

swindling for the past 20 years." Roche sued. Ultimately the trial court found for Roche and awarded him

one farthing, each party to bear their own costs and counsel fees. Roche appealed and the case

was retried in London. This time, Roche was awarded £5. Fees and costs, however, were assessed against

Sir Timothy, the amount of which for the two trials practically broke Sir Timothy. One moment of

hilarity arose during the trial:

WITNESS: Lord Fermoy grabbed Sir Timothy's bridle.

THE JUDGE: For legal accuracy, was it the horse's bridle or Sir Timothy's?

WITNESS: The horses, my Lord, Sir Timothy was not bridled that day.

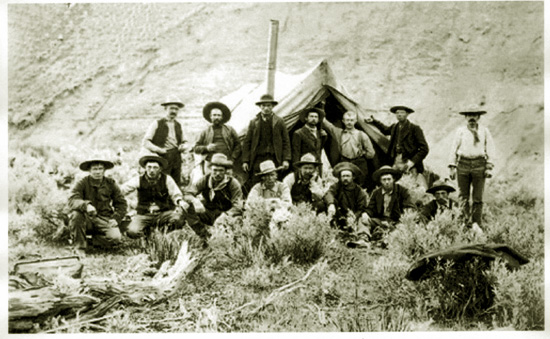

Scene from Roundup on the "76," 1884.

Frewen expanded the ranch's operations. The range was expanded down to Rawhide south of present-day Lusk and

northward into Montana along the

Tongue. It also expanded operations into Wisconsin and Alberta.

Nevertheless the losses increased. To overcome the losses, Frewen started a fattening station at the end of

Lake Superior where cattle would be fattened for live shipment to

the United Kingdom via Canada.The whole scheme was dependent upon an ability to ship via Canada without paying duties and securing

Empire preference. We have all known persons who hear only that which they wamt tp believe. Apparently, Frewen

believed that there would be no problem in avoiding Empire Preference.

On the way to the United Kingdom to

secure Privy Council approval Frewen stopped by Ottawa to see his "friend" Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald. Moreton read

a bit too much into Sir John's words. In Melton Frewen, p. 119 Moreton wrote,

On my way home I saw my friend, Sir John A. Macdonald, at Ottawa, who cordially welcomed the project,

and handed me over to his Minister of Agriculture, Mr. J. Henry Pope.

Mr. Pope was what the Americans call a broad-gauge man and recognised

that such a transit trade would not merely bring a vast accession of

business to the Canadian railroads but would make of Montreal a cattle

market second only to Chicago itself on the North American Continent.

In the full conviction that the forces at the western end were all in line

I sailed for England in July.

And what were Sir John's actual thoughts? As reported on the wire services:

Sir John Macdonald,referring to Mr. Frewen's Wyoming

cattle scheme which was the shipment by the Canadian Pacific railway and thence down the lakes to Montreal of

Wyoming and Montana cattle to the British markets, expresses unqualified

condemnation of the project as detrimental to the beef interests of the dominion. Rock Island Argus, Aug. 26, 1895, p. 3.

Not withstanding that he had not obtained approval for shipment of live cattle to Britain, Frewen went ahead and

constructed the feed lot. See Ft. Benton River Press, Sept 16, 1885.

The feeding station at Superior was sold at a loss. Apparently both Moreton Frewen and Horace

Plunket believed that if the property could be held onto, it would see at a profit. It may be

speculated that Frewen sold because of the need for cash.

On the north side of the railroad tracks at Sherman Hill, opposite the Ames Monument, Frewen

constructed a meat packing plant. The cost was estimated at between $30,000 to

$40,000. The location of the plant on Sherman Hill would avoid the

necessity of refrigeration. Few cattle were moved to Alberta.

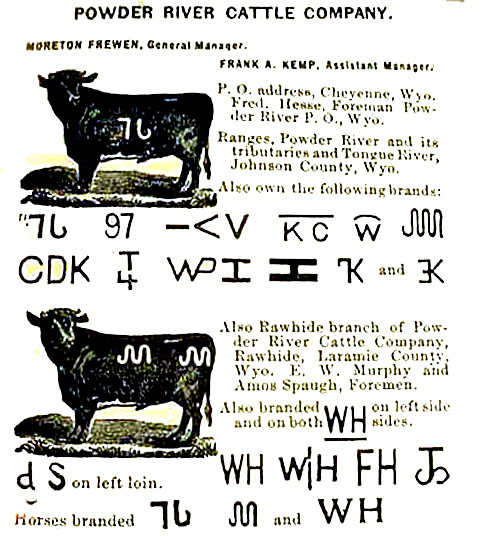

Brands, Powder River Cattle Company

On a bright and sunny morning in June, 1885,

Moreton Frewen turned his horse south from the log mansion, never to return. See "Melton Mowbray," p. 125. Deep down

Within Morton's heart, there was a realization that the enterprise was a failure:

On June 23rd, 1885, I made this note in the ranch visitors' book: 'Am leaving to-morrow via Superior for England,

and this abode of pleasant memories and good sport is to be abandoned.

The pressure of settlement is driving us cattle-men northward,

nor shall we secure permanent quarters south of leased ranges in Alberta.'

Instead, Moreton made one of his numerous trips to the U.K in a vain attempt to raise

more money. The 1886 membership rolls of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association show his address as

Superior, Wisconsin. With calls on the shareholders for loans or further investments, the Shareholders had enough. Some would make further investment or loans, but only on the

condition that Frewen would be dismissed. His stock in Powder River was worthless. He was broke. Moreton, in spite of threats of lawsuits and an

actual lawsuit and two acrimonious directors meetings, was discharged. Horace Plunket who had an interest in the adjacent "E K"

ranch was employed to liquidate the

ranch. In August 1888 Plunket was in Alberta still still cleaning up the mess. See Plunket Diaries August 1888.

Next Page, Moreton Frewen continued.

|