|

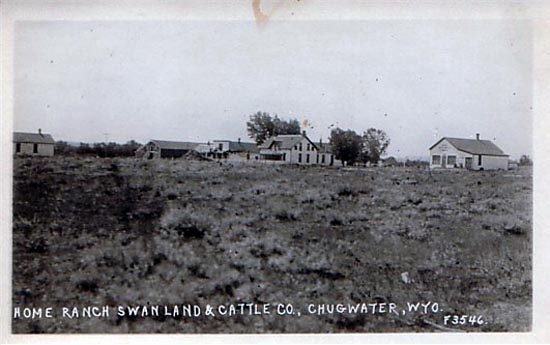

Swan Land & Cattle Company, Limited, Chugwater, 1914

Photo courtesy of Brian Dunlop.

The above view is of the home ranch of

the Swan Land & Cattle Company, commonly referred to as the "Two-Bar." At the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of

the 20th, Swan was, perhaps, the epitome of the popular conception of the large corporate cattle company. At one

time the Company controlled an area greater than the size of the State of Connecticut. Its managers were

influential with the Wyoming Stock Growers Association and it has been in the popular mind associated with

the depredations of the self-styled "cattle detective" Tom Horn, featured on subsequent pages.

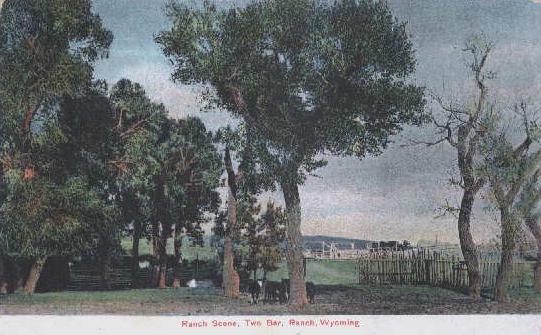

The Two Bar, Chugwater, 1912

The center building, shown in the above photo, burned in 1918. For another view see Deadwood Stage page.

Modern view of headquarters building and interior of barn below. The manager's residence was originally

constructed by Thomas A. Maxwell about 1876. By the time of the above view it had been

added to several times. Maxwell's widow sold the home ranch to Swan Land & Cattle Co. in 1882.

Chugwater was the corporate headquarters for the Swan Land and Cattle Co.

The home ranch of the Two Bar, approx. 1901,

Although, the home ranch for Swan was in Chugwater, the company owned a number of separate ranches. In the Chugwater area were

the Kelly place depicted on the previous page located a few miles away, the Muleshoe located on Sybille Creek,

and the Two-Bar southwest of Wheatland. Each had their own home ranch.

The home ranch of the Muleshoe, approx. 1901,

The Muleshoe, not to be confused with the Mule Shoe near Big Piney, was originally founded by Charles W. Wulfjen, the father-in-law of John Kendrick who served as foreman and late owner of the OW, governor and

United States Senator. In the early 1880's Swan purchased the ranch for $280,000. It brand, mainly on horses, was an inverted U. The Two-Bar was mainly used on

cattle.

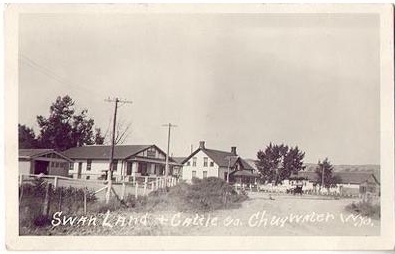

Modern view of Swan Land & Cattle Company home ranch.

In the 1870's, stockgrowers discovered that cattle could winter over on the northern plains.

In the early 1880's speculative fever overtook the industry, fueled by books such as

James Brisbin's 1881 book The Beef Bonanza, or, How to Get Rich on the Plains and J. S. Tait's

brochure The Cattlefields of the Far West. Tait estimated that investors could earn profits as

much as 33 to 66 percent. Indeed, some did earn large profits. Charles Goodnight made $600,000 in just ten years.

His partner in the JA Ranch, John G. Adair of Ireland parlayed $360,000 to a value of $3,000,000. In November, 1882, Alexander Hamilton Swan (1831-1905), president of three

cattle companies, Swan & Frank Live-Stock Company, National Cattle Company, and the Swan, Frank & Anthony

Cattle Company, along with James Converse, Joseph Frank and Godfrey Syndacker, entered into a transaction with James Wilson of Edinburgh, Scotland, whereby there was sold

in March, 1883, for the sum of $2,553,825 to the Swan Land & Cattle Company, Limited, a British

limited liability company:

"all and singular the lands and tenements, water rights, improvements upon lands, houses, barns, stables,

corrals, and other improvements and grazing privileges; also all live stock,

consisting of neat cattle, horses and mules, belonging to the said three Wyoming corporations, or any

or either of them; also all live stock, brands, tools, implements, wagons,

harness, ranch, camp, and round-up outfits, and branding irons"

Swan produced to the investors herd books, which he represented as being accurate, showing 89,167 cattle.

Swan, at a later time, was quoted as stating:

In our business we are often compelled to do certain things which, to the

inexperienced, seem a little crooked.

Scene on the Two-Bar, undated

As a part of the transaction Swan was employed as general manager at a

salary of $10,000.00 a year, this at a time when highpaid cowboys would dream of working for the

"Two-Bar"

for $45.00 per month plus the promise of rice 'n raisin pudding for dessert. The following year, 1884, the Company purchased

from the Union Pacific 550,000 acres for $2,300,000, giving it control over

3.25 million acres. The Company owned more than 100 brands. It was required publish a brand book so that

its foremen would be able to keep up with the Company's brands. The home ranch in

Chugwater was connected to Company headquarters in Cheyenne by a telephone

line that cost the Company £1,000 to install. Additionally, the company maintained

its own hotel in Cheyenne for personel visiting the headquarters.

Interior of

barn, Swan Home Ranch. Exterior, 1909 color view above.

Following the "Die off" of 1886-1887, discussed with regard to

cattle drives, the Company contended that the herd books had been

falsified, that the actual number of cattle was at least 30,000 less than represented and

the Company had been cheated out of more than $800,000. Needless to say, Swan was

fired and Scottish-born John Clay (1851-1934) became general manager.

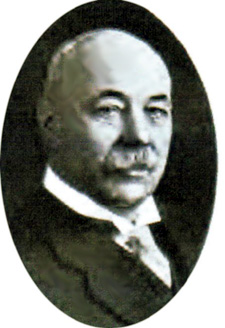

Left, Alexander H. Swan. . . . .Right, John Clay.

Of Swan, Clay later wrote in My Life on the Range that "Sycophants in abundance buzzed

round him and he was swept off his feet by hero worship."

Alvin H. Sanders, editor of the Breeder's Gazette, in his The Story of the Herefords, The Breeder's

Gazette, Chicago, 1914, quoting a correspondent of his paper, described the hero worship with

which Swan was greeted when he returned to his old home town in Iowa where he maintained a breeding

operation:

[W]hen it was known that Swan was coming to town, the word would be passed from one to another, * * * * and a

spirit of suppressed exitement pervaded the little town as if awaiting a visit from the

President of the United States. His partners, various employees and other

retainers would repair to the railway station an hour before train-time * * *. When the train would at

last arrive Swan would come off with his following of Englishmen and eastern capitalists and

lead the way to the hotel like a lord, passing out greetings and shaking hands on all sides.

John Clay in his description of Swan continued:

"[He was]about six feet and an inch, and wherever he went he made an imposing

figure. His face was close shaven, he had a keen eye, a Duke of Wellington nose, and

gold teeth. While his manner was casual it was magnetic and he had a great following.

At Cheyenne, groups of men sat around him in his office and worshipped at

his feet. In Chicago he was courted by bankers, commission men, and breeders of

fine cattle, in fact, all classes of people in the livestock business. The

mercantile agencies rated him at a million, while I doubt, so far as the

range is concerned, if he ever owned an honest dollar."

Clay is also noted as

having served as the President of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association and managed other British-owned ranches. Swan had previous served also as president of the Association and was

also was instrumental in the formation of the Wyoming Hereford Association.

Although Hereford had previously been introduced to Wyoming in 1878 by Swan and J. M. Carey, primary credit should go to

the Wyoming Hereford Association which brought

Herefords to Wyoming at the Kingman Ranch near Cheyenne.

The Kingman Ranch is a predecessor of the Wyoming Hereford Ranch on Campstool Road southeast of Cheyenne.

Swan Land and Cattle Co., Chugwater, 1921

The Two-Bar was not the only ranch with suspect herd books. The Iron Mountain Cattle Company

was owned by John C. Coble and Henry C. Bosler. In 1903, Bosler bought out the interest of

his partner. There then ensued a bitter lawsuit between the two. Bosler accused

Coble of keeping two sets of herd books and that Coble had displayed the set with

the larger herd to fraudulently induce Bosler into making a loan. Coble accused

Bosler of deliberately forcing the ranch into losing money. Both accused the

other of incompetence.

In Texas, the Rocking Chair was

owned by Sir Edward Morjoribanks and the Earl of Aberdeen, later Governor General of Canada,

John Campbell Hamilton Gordon. When financial statements didn't seem to match

actual performance, Sir Edward and Lord Aberdeen arrived unannounced and requested

a cattle census. The ranch manager ran the cattle past the tellers and around a

hill so that they were counted multiple times. A similar story has been told with regard

to Moreton Frewen, see Cattle, in which it is alleged that Frewen bought the same herd twice, with the

unscrupulous seller driving the herd around a hill twice, making Frewen believe the herd

to be twice its true size. Allegedly, Frewen was cheated by Chico Springs, New Mexico Territory,

cattle baron Stephen Wallace Dorsey who instructed that two herds be run around the hill twice.

Supposedly in the herd was an old yellow, lop-horned, lame steer known as "Old Buck." After the one

herd had passed by several times, Dorsey became concerned that his naive

buyer might notice that the same steer was being counted multiple times. Thus,

Dorsey instructed his foreman to cut Old Buck out and separate him from the

herd. Soon, however, Old Buck made his way back into the herd. Once again,

Old Buck was separated, this time by a further distance. Once again, Old Buck was back in

the herd. The legend arose, that a week later Old Buck was still circling the hill and that, even today, on a

moonlit night the ghost of Old Buck may be seen limping along around the hill. The legend gave rise

to Frank Benton's 1903 Old Buck's Ghost:

Down in New Mexico, where the plains are brown and sere,

There is a ghostly story of a yellow spectral steer.

His spirit wanders always when the moon is shining bright.

One horn is lopping downwards, the other sticks upright.

On three legs he comes limping, as the fourth is sore and lame;

His left eye is quite sightless, but still this steer is game.

Many times he was bought and counted by a dude with a monocle in his eye;

The steer kept limping round a mountain to be counted by that guy.

When footsore, weary, gasping, he laid him down at last,

His good eye quit its winking; counting was a matter of the past;

But his spirit keeps a tramping 'round that mountain trail,

And that's the cause, says Packsaddle, that I have told this tale.

From Frank Benton's Cowboy Life on the Sidetrack,

The Western Stories Syndicate, 1903.

|

Dorsey's reputation for fraud became such that the story is entirely believable. Dorsey was involved

in the Star Route mail scandals and in the New Mexico land frauds. In the latter, numerous persons

in New Mexico were indicted including Dorsey. Most cases, however, failed when

the court files were stolen out of the courthouses. Dorsey, only one year following his discharge in

bankruptcy in Arkansas, commenced the construction of his mansion near Clayton, New Mexico

Territory. The mansion was even more magnificent that Moreton Frewen's and boasted a solid

cherry staircase. Dorsey ultimately went broke a second time and the mansion was sold

at auction. It was turned into a sanatorium for consumptives.

It has also been contended that the one who cheated Frewen was Tim Foley. Young British investors had

a reputation for gullibility. The French economst Paul De Rousiers, American Life, Firmin-Didot & Co., New York, 1892, toured

the Standard Cattle Company. Its manager made an off-hand comment relating to a surplus barn, "I must

sell it to an Englishman." De Rosiers could not understand why the manager wished a British buyer. The

manager responded:

"It is an expression in this country. When we wish to get rid of some encumbrance at a high price, we cannot count on getting it from

Americans, who are too practical and too primitive in their ways of working to risk it, but a

young Englishman, newly landed, is inexperienced and has money in his pocket, and will easilty believe

in the utility of such a thing as he is used to a complicated and advanced agrriculture in Europe."

De Rousiers commented:

It is the same in Switzerland, where the English tourists are generally provided with a host of things -- field glasses, plaids,

baskets of provisions, pocket medicine-chests, water-proofs, etc. of which more are hinderances than

useful. The American tries to simplify and goes around the

worlds without luggage, in a flannel shirt and a celluloid collar. The same

contrast can be seen in everything.

Moreton Frewen in his Melton Mowbray and Other Memories J. Jenkins, London, 1924, denied that

he had been taken.

The losses at the Rocking Chair grew, however, so

that ultimately they could not be concealed. Sir Edward and Lord Aberdeen again

appeared, terminated the manager and unsuccessfully sued. Notwithstanding a new more honest

manager, the Rocking Chair was past redemption and was placed in the hands of

a liquidator who sold it to the Mill Iron. In contrast to the loose management style of

Sir Edward and Lord Aberdeen, was the control maintained over the Matador where complete inventories and

details of operations were cabled weekly to the board of directors in Dundee. To keep

the cable bills down, codes were used.

The owners of the Two-Bar sued Swan in a case going to the U.S. Supreme Court, but were

unable to collect. The Company was so large, however, that it had no choice

but to continue in business, slowly reducing its dependence on cattle and by 1909

had turned entirely to sheep. By 1917, the Company's finances had been completely

restored. In 1926, the Company was reorganized, in order to avoid British taxes,

as an American corporation organized under the laws of Delaware. In 1948,

the company's assets were liquidated with the last dividend of $1.55 a share

being paid in 1951.

Next page, Chugwater Continued.

|