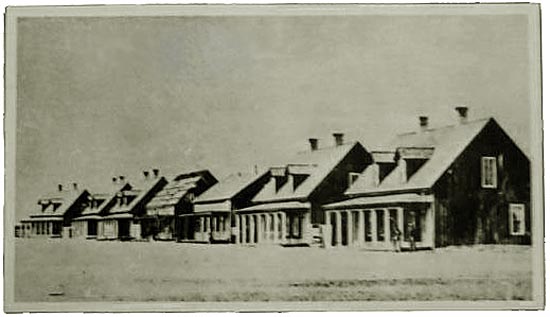

Fort D. A. Russell, 1868. Officers' Row in the distance. The center two-story building is the

Commanding

Officer's quarters. Photo by Alexander Gardner

For much of its existence, even as late as the 1920's, Fort D. A. Russell (now Warren Air Force Base), northwest of

Cheyenne on Crow Creek, was a cavalry post. As discussed with regard to the Union

Pacific Railroad, during the Civil War the Northern Congress passed legislation providing for the

construction of a railroad connecting California with the east. There was a realization

that the construction would require protection from the Indians. The legislation, therefore,

provided for the President to establish a fort near the intersection of the

railroad with the Front Range. Thus, on July 4, 1867, Fort D. A. Russell was established near a place called

"Crow Creek Crossing," now Cheyenne. The site of the fort was selected by Gen. C. C. Augur. Augur was one of the

Union Commanders at the seige of Port Hudson, Louisiana, discussed below with regard to

Francis E. Warren, after whom the fort was later re-named.

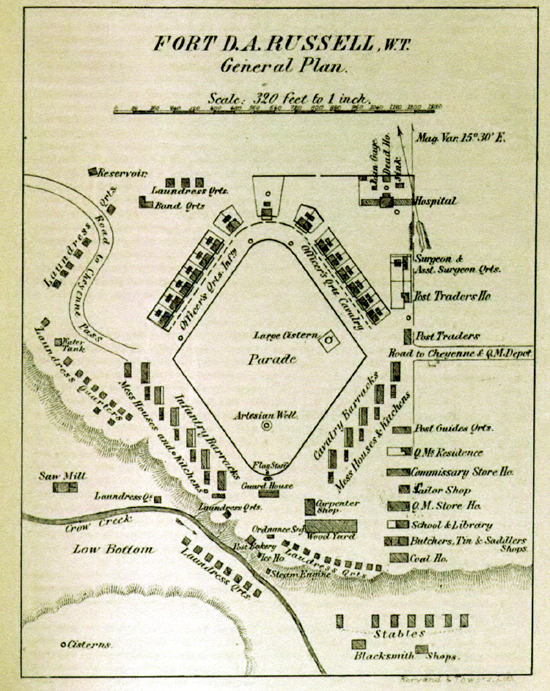

Plan of Fort D. A. Russell, 1888, prior to reconstruction

The initial fort was never stockaded, but always on an open plan. Its initial commander was Col. (Brevet Major General Volunteers, Brevet Brig. Gen. Regular Army)

John D. Stevenson. The first structures

consisted of log cabins for the enlisted men. During the first winter, officers remained bivouacked in tents. Other forts

established for the protection of the railroad included Fort Sanders south of

present day Laramie, Fort Fred Steele where the railroad crosses the Platte, and

Fort Bridger originally acquired by the military as a part of the Mormon War. The need for such forts was critical. Gen. Augur noted in an

1867 report, the fort was necessitated for protection of the railroad, but that the

overland mail stages required guards at their stations between Julesburg and Denver and between Forts Sanders and Bridger. Guards were required

to accompany coaches as parts of the routes. The telegraph line also required guards at some of

the stations and men assigned to repair the lines required escourts. The surveyor-general of Nebraska was also making demands for escorts for

some of his surveying parties. He noted that that his command was broken up and "scattered, as it were, over this country, a necessity

very destructive in its results upon the discipline and instruction of both officers and men."

Men on porch of unidentified building (possibly the post hospital), Fort D. A. Russell.

The initial buildings were crudely constructed of board and batton.The barracks were insulated with adobe in the walls, but the area

around the eaves were open from the shrinking of the lumber. Thus, one surgeon, in an

1870 report noted that the ventilation was "amply sufficient." The enlisted men's bunks were

were equipped with mattresses filled with hay, two men per bunk. Each barracks had its own seperate

kitchen constructed of logs. The officers quarters were larger but had no plumbing. To keep out the

cold, the rooms were lined with tarpapper which was then wallpapered. In the hospital, it was necessary to line the

ceilings with tarpaper. The building were shakey and, thus, in the wind plaster could not be used as it would be

constantly falling down.

Officers' Row, 1868.

Initial construction, in addition to being poor, was slow. The quartermaster employed men on salary to assist in the construction.

Enlisted men were also utilized even though they had no construction experience. The salaried men were slow, seemingly extending the

lenght of their employment through the winter. Desertion was rampant. Clayton K. S. Chun, U.S. Army; the Plains Indian Wars, 1865-1891, Osprey Publishing, 2004,

estimated that approximately 1/3rd of all enlistments ended "in some form of desertion. He noted that out of

255,000 enlistments during the period, there were in excess of 88,000 desertions. Indeed, in one expedition out of the fort,

some 65 men deserted by the time the troop readed Lodge Pole Creek, taking government horses and weapons with them. Although some deserted were caught,

it was easy to change one's name, and obtain employment on the railroad or elsewhere for substantially more pay. Other reasons were given by the military,

the troops were not fighting Inidans but, instead sat around bored or were used for non-military puposes such as

carpenters and masons.

The ease with which one could change one's name is, perhaps, illustrated by a

French immigrant who enlisted in the army, was stationed at Fort D. A. Russell, deserted in 1870 and went to the

bright lights of Denver, Adolphe François Gérard. In Denver, under his new name of Louis Dupuy, he gained employment as

a correspondent for the Rocky Mountain News reported from the mining camps. He took a job as a miner, was injured, and

acquired a bakery in Georgetown. The bakery was expanded into the Hotel de Paris, famous throughout the Rocky Mountain West for its

French restaurant. His secret was never revealed until after his death.

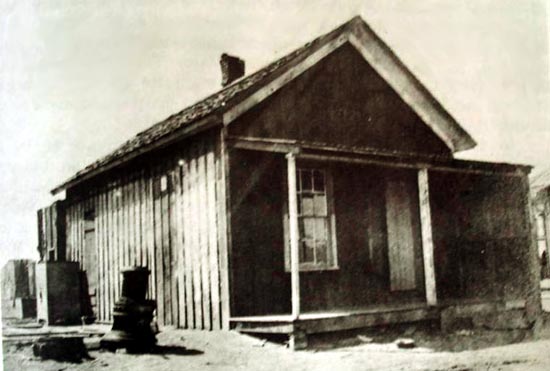

Fort D. A. Russell, building used for launderesses or as a married men's quarters.

The married men's and launderess's quarters were, as illustrated in the above photo, also of board and batton, equally leaky and lined with

tarpaper. The building in the photo cost $196.00 to build.

The commander of one western fort blamed desertion on "opportunities for indulgence in dissapation." He argued, "Men who dissipate all night do not feel much like

attending to duty in the morning." Certainly from its founding Cheyenne provided an opportunity for

dissapation. In 1870, as an example, one newspaper complained about a "house of loose architecture." By 1900, there were at least 15 such houses mostly on

the west end of town, convenient to the fort. Indeed, the convenience was made easier by the presence of the street railway which charged only a nickle for the

ride into town. Before the street railway, on post were "launderesses." At D. A. Russell in 1877, there were some 24 launderesses.

Five were married. Of the reminder, 17 had children. In 1912, the city began to crack down on the

cheap parlor houses by increasing the monthly fines.

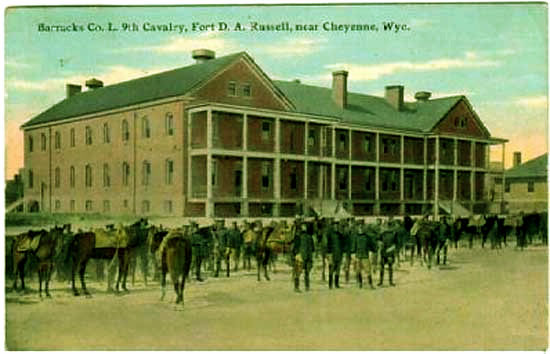

Barracks, Troop L, 9th Cavalry, approx. 1909.

In 1884, the fort was designated as a permanent installation. The advantage of the fort was that it was on major railroads and

midway between the Canadian and Mexican borders. Thus, there began a program of

reconstruction of the fort as depicted in the remaining photos.

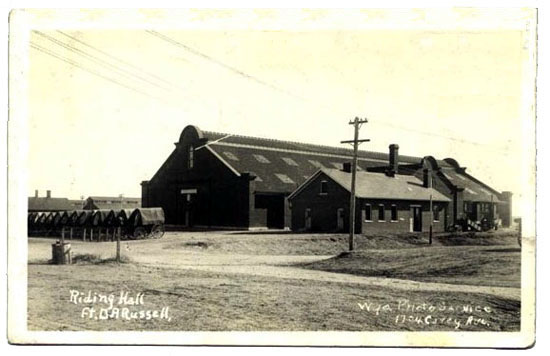

Riding Hall with supply wagons parked in front.

The fort was named after

Brig. Gen. [Brevet Major General] David Alan Russell, who was killed at the

Battle of Opequon Creek near Winchester, Va., on Sept. 19, 1864. His Confederate opposite, Major Gen. Robert

E. Rhodes, was killed in the same battle. As a note, Union forces named battles after

adjacent creeks, while Confederate forces named the battles after nearby towns, i. e.

First Manassas and Second Manassas were named by the Confederates after the nearby

town of Manassas, Virginia, and are the same battles as First Bull Run and Second Bull Run named by the

Union after the nearby creek. Accordingly, some sources refer to Russell as being killed at

Winchester.

Supply Wagons for 315th Cavalry.

The 315th was organized in 1917 and was disbanded during World War II. With the fort's central location midway between the Canadian and Mexican borders and halfway between

the two coasts on a railroad, the fort rapidly became a central supply point for the

military in the central United States.

Stables, Fort Russell, undated.

In 1884, the fort was made a permanent installation. The following year

a program of building the structures depicted on this page began. In 1886, the 9th Cavalry of

"Buffalo Soldiers" was asigned to the post. The fort at one time became the

largest cavalry post in the country. Cavalry remained at the fort until 1927.

Cavalry, Ft. D. A. Russell, 1925. Photo by J. Shimitz.

Next page: Fort D. A. Russell continued.

|