|

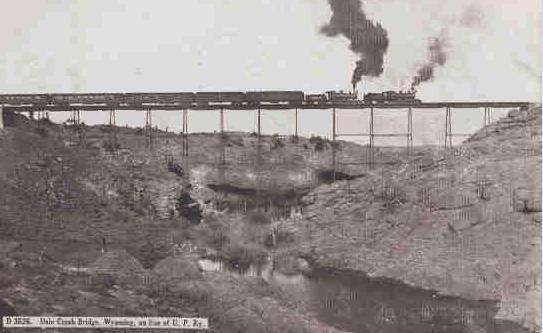

Dale Creek Trestle, 1869, A.J. Russell

As discussed below the Dale Creek trestle was the highest bridge on

the Union Pacific. A. J. Russell was employed during the Civil War by Matthew Brady with some of the

photographs commonly attributed to Brady being, in fact, taken by Russell. Following the war

Russell served the Federal Government on some of the surveying expeditions in the west before being employed by

the Union Pacific. For additional view of trestle see below right.

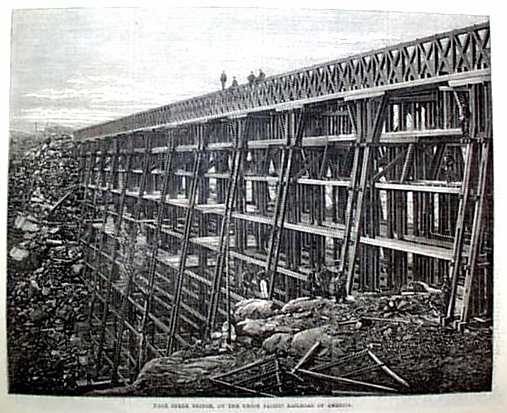

Dale Creek Bridge under construction, engraving,

Harper's Weekly, 1868

.Dale Creek Trestle

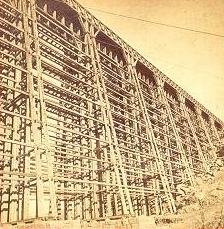

The Dale Creek Trestle, originally built of wood, pictured at the top of the

page, was later replaced with one made of iron depicted below. At the time

it was regarded as an engineering

marvel, 150 feet above the creek bed and the longest trestle on Railroad. The

masonry foundation was commenced in December of 1867 and on April 21, 1868 the rails

were laid across the bridge. The wooden bridge was replaced with an iron bridge.

Henry T. Williams described the iron bridge:

"Dale Creek Bridge -- is about two miles west of Sherman. This bridge is built of iron, and seems to

be a light airy structure, but is really very substantial. The creek,

like a thread of silver, winds its devious way in the

depths below, and is soon lost to sight as you pass rapidly down the

grade and through the granite cuts and snow sheds beyond. This bridge is

450 feet long, and nearly 130 feet high, and is one of the wonders

on the great trans-continental route. A water tank, just beyond it, is

supplied with water from the creek by means of a steam pump. The buildings

in the valley below seem small in the distance, though they are not a great way off. The old

wagon road crossed the creek down a ravine, on the right side of the

track, and the remains of the bridge may still be seen. This stream rises about six miles north of the

bridge, and is fed by numerous springs and tributaries, running in a general southerly

direction, until it empities into the Cache La Poudre River. The old overland road

from Denver to California ascended this river and creek until it struck the

head-waters of the Laramie. Leaving Dale Creek bridge, the road soon turns to the right, and

before you, on the left, is spread out, like a magnificent panorama,

The Great Laramie Plains."

The Bridge at Dale Creek

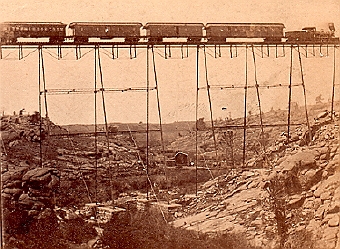

Dale Creek Bridge viewed from below, photo by A. J. Russell

Dale Creek Bridge viewed from below, photo by A. J. Russell

While it may have been the wonder of the age, it was terrifying.

The bridge would sway in the wind and trains were

required to slow to four miles per hour while crossing it, even though, as shown in the above engraving, guy wires were attached to the

bridge. Adding to the terror was the wind which seemingly threatened to

blow the cars off the bridge. Ellen G. White described her 1873 passage over Dale Creek:

The scenery over the plains has been uninteresting. Our curiosity is excited

somewhat in seeing mud cabins, adobe houses and sagebrush in abundance. But

on we go. From Cheyenne the engines toiled up, up the summit against the

most fearful wind. The iron horses are slowly dragging the cars

up the mountain to Sherman. Fears are expressed of danger, because of

the wind, in crossing the Dale Creek bridge--650 feet long and 126 feet

high---spanning Dale creek from bluff to bluff. This trestle bridge looks

like a light, frail thing to bear so great weight. But fears are not

expressed because of the frail appearance of the bridge, but in regard

to the tempest of wind, so fierce that we fear the cars may be blown

from the track. In the providence of God the wind decreased. Its terrible

wail is subdued to pitiful sobs and sighs, and we passed safely over the

dreaded bridge. We reached the summit. The extra engine was removed.

We are upon an elevation of 7,857 feet. No steam is required at this

point to forward the train, for the down grade is sufficient for us

to glide swiftly along.

As we pass on down an embankment we see the ruins of a freight car

that had been thrown from the track. Men were actively at work upon

the shattered cars. We are told that the freight train broke through

the bridge one week ago. Two hours behind this unfortunate train came

the passenger cars. Had this accident happened to them, many lives must

have been lost.

Mrs. White was not the only one to write of the terror of the bridge. Rae expressed concern with the rapidity

of the bridge's construction. He noted that the "contractors are said to baost of having erected it

in the short space of thirty days. It is not stated how many days the bridge will

bear the strain almost hourly put upon it."

By 1876, the wooden bridge was replaced by an iron bridge, which, itself, was hardly less

terrifying. It too required guy wires, and the view out the windows of the

passenger coaches would hardly have been reassuring, giving the impression that the

train was floating in mid-air. Today, the line has

been relocated and nothing is left except the foundation piers.

The Great Iron Bridge at Dale Creek, undated

The reason for the haste in the building of the railroad was the race with the Central Pacific to

reach Utah. Originally, the Central Pacific was limited to a distance no more eastwart than

150 miles of the Nevada-California border. That was lifted and once Nevada was reached, construction continued

apace while the Union Pacific was slowed down in the crossing of the Wasatch. Ultimately, Congress

resolved the issue and decreed that the junction point was to be Promontory Point north of Ogden. In the race,

the Union Pacific on the Utah Plains achieved a record of eight miles in one 10 hour day. Shortly

before the junction, the Central Pacific beat the record and made 10 miles in one day.

Great Iron Bridge at Dale Creek, photo by Charles Weitfle

Great Iron Bridge at Dale Creek, photo by Charles Weitfle

For information as to Charles Weitfle see next page.

Originally, the date for the junction was set to be May 8, 1869. Governor Stanford, President of

the Central Pacific arrived. California and Nevada each sent golden spikes. A special hand-rubbed

laural tie was created for the ocassion. The Union Pacific sent a silver plated sledge for the

ceremony. Unfortunately, Vice President Durant of the Union Pacific was delayed. Railroad workmen

complaining about unpaid backpay, disconnected Durant's private car from his train and

chained it to the rails until arrangements were made for the money. Ultimately, the ceremony was

conducted on May 10 with President Stanford and Vice President Durant to drive the

two spikes. They both missed. After both spikes were driven, the two locomotives were placed

nose-to-nose while C. R. Savage took a photo.

From Dale Creek the trains descended to Laramie. As noted by Mrs. White, the trains required no steam

for the descent. Indeed, the downward trip into Laramie was also fearful. Rae noted:

Dowards speeds the train, at a pace which makes one shudder at the consequences of an accident. In twenty

miles the descent of a thousand feet is accomplished. No steam power is employed. On the

contrary, the brakes are tightly screwed down alike on the locomotive and the cars.

Next Page: Snow Removal, Palace Cars, Dining Service.

|