"Waiting for a Chinook," C. M. Russell, approx. 1903

Although the editor of the Sheridan

City Directory, as noted on the Sheridan Page, may have believed that "in winter the

friendly 'chinook' wind mitigates the cold, killing winters of the Dakotas,"

as illustrated by C. M. Russell's famous sketch above, chinooks are somewhat unreliable.

In 1886 Charlie Russell was employed by Kaufman and Stadler. Kaufman wrote

asking how the cattle had fared. The response by Russell was a sketch of a

starving cow in the snow. Kaufman displayed the sketch in his office which led

to its popularity with requests of Russell for more copies. The version shown to the

right was painted about 1903.

As discussed lower on the page, the winter of 1886-1887 was devastating to the cattle

industry on the Northern Great Plains. While the era of large corporately owned cattle oerations continued until about 1905 when the last of the big roundups in Wyoming

was cancelled by the WSGA, 1887 denotes the beginning of the end. Along the Cheyenne, the last big roundup was in

1902. The winter of 1901-1902 was especially severe causing cattle to drift south onto the Rosebud Reservation and further

south along the White and Cheyenne Rivers. In 1902, the government ordered all open range cattle to be moved

off the Reservation. On the Roundup some 13 to 18 wagons and 400 to 500 cowboys and 4000 horses particiapted. The roundup took

three months and gathered an estimated 45 to 50,000 head. In 1948, some of the cowboys participating formed the

"Big Roundup club." Reunions continued as the numbers dwindled to the call of the "Last Roundup." Today, descendents of those on the 1902 roundup continue to meet.

Smaller roundups continued. By 1919 the last of the big cattle companies left the Dakotas. In Wyoming, Swan Land and Cattle Company, Ltd, closed its doors in

1948.

A Blizzard on the Plains, Harper's Weekly, 1886

In the early 1880's a discussed with regard to the Swan Land and

Cattle Company , a cattle boom swept the Great Plains, attracting many eastern and

British investors. As observed by John Clay,"Drawing rooms buzzed with the stories of this last of bonanzas; staid old gentlemen, who scarcely knew the diffrence between a steer and a heifer, discussed

it over their port and nuts." Indeed, the discussions were among those who scarcely knew where Wyoming was. Moreton Frewen, managing partner of the "76," the second largest

cattle company in Wyoming discussed on the next page,

attempted to obtain permission from the Privy Council to ship live Wyoming cattle to Britain to be fattened there. He was

introduced as a representative of the Governor of Wyoming, a territory "west of Lake Michigan." well, in a sense it is accurate, Wyoming is

west of Lake Michigan, but there is a fair amount of acreage in between. In his enthusiasm, Frewen tended to stretch support for his scheme.

He told the Privy Council that the Canadian Governor General and the Agricultural Minister were in favor of the

proposal, He represented to the Stock Growers's convention that the British were in favor of it. Neither was true. Why would the Canadians cut off

their own stockmen? Why would the British Government endorse a scheme to cut off stock sales from Ireland where most of the

British feeding stock came from?

With the large production of cattle, beef prices fell during 1886. Premonitions of a coming problem were ignored.

Sir Samuel Baker when he visited the "76" was warned by some of the old cowboys. He later wrote in his 1890 Wild Beasts and Their Ways:

It was beyond my province to enter upon the question of successful ranching,

but the Americans confided to me that the prairie grass, instead of benefiting

by the pasturing of cattle, became exhausted, and that weeds usurped the place of the

grass, which disappeared; therefore it would follow that a given area, that would

support 10,000 head of cattle at the present time, would in a few years only support

half that number. It might therefore be inferred that the process of deterioration

would ultimately result in the loss of pasturage, and the necessary diminution in the herds.

In addition to the fall of prices, the summer of 1886 was dry reducing the growth of the prairie grass.

Holding the cattle over only exacerbated the overgrazing. It was a recipie for disaster.

Although the editor of the Sheridan

City Directory, as noted on the Sheridan Page, may have believed that "in winter the

friendly 'chinook' wind mitigates the cold, killing winters of the Dakotas,"

as illustrated by C. M. Russell's famous sketch pictured lower on the page, chinooks are somewhat unreliable.

The winter of 1886-1887 was devasting to Wyoming's cattle industry. The giant British-owned Swan Land & Cattle Company, Limited,

headquartered in Chugwater and Cheyenne, lost 50% of its calves and 15 to 20% of its entire stock.

On one wintry day across the street from the Cheyenne Club, ranchmen gathered in Luke Murrin's saloon to lament their losses.

Luke, realizing that herds were often sold by "book count" rather than actual census, offered the assurance,

"Cheer up boys, whatever happens, the books won't freeze." It did little to assuage

their fears. Nor was their confidence helped when on January 1, 1887, when the giant Dolores Land and Cattle Company, owned by

Gilbert A. Searight and his family made an assignment for the benefit of creditors. The previous

year Searight sold the Goose Egg Ranch on Poison Spider Creek to J. M. Cary and Brother losing an

estimated $200,000.00 in the transaction. According to the Fort Worth Daily Gazette, January 3, 1897, The Dolores Land and Cattle Company was

regarded as one of the wealthiest cattle organizations. It was capitalized at $2,000,000. Searight had been used by

William Makepeace Thayer in his 1887 "Marvels of the New West as an example of the fortunes to be made

in the cattle business.

On May 14, 1887, cattle interests in Wyoming were further shaken when

Alexander Swan and his brother Thomas Swan declared their insolvency and entered into a

general assignment of assets for the benefit of creditors. Less than a month before, the Swan Brothers'

accountant had declared to the First National Bank of Cheyenne that the two were

worth more than $800,000.00 above liabillities. Shortly thereafter, creditors, bankers, and lawyers began gathering

around the Cheyenne Land & Live-Stock Company which had extensive land and

irrigation holdings along Horse Creek. And like prairie wolves the creditors were

soon fighting amongst themselves as they picked at the carcass. Other large companies

such as the Niobrara Land and Cattle

Company which had interests from Texas to Montana failed. In the instance of the Swan Land and Cattle Co. fraud, as discussed on the Chugwater page,

may also have contributed to large losses.

On November 13, 1886, it started

to snow and continued for a month. In mid-December, however, there was a

thaw, turning the snow to slush. In late December the temperature turned to

the minus 30's, turning the slush to a solid sheet of ice. January of 1887, was the coldest in memory and included one

72-hour blizzard. Teddy Blue Abbott, who received his nickname as a result of an

incident with a soiled dove in Miles City, Mt., noted:

"It was all so slow, plunging after them through the deep snow . . . .The horses' feet were cut and bleeding from the

heavy crust, the cattle had the hair and hide wore off their legs to the knees and the hocks.

It was surely hell to see big four-year-old steers just able to stagger along. It was the same all

over Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado, western Nebraska, and western Kansas."

Supply Train in a Blizzard " 1892.

Theodore Roosevelt who owned a ranch in Dakota Territory described the scene when Spring thaw came:

It would be impossible to imagine any sight more dreary and melancholy

than that offered by the ranges

when the snow went off in March. The land was a mere barren waste;

not a green thing could be seen; the dead grass eaten off till the

country looked as if it had been shaved with a razor. Occasionally

among the desolate hills a rider would come across a band of gaunt,

hollow-flanked cattle feebly cropping the sparse, dry pasturage,

too listless to move out of the way; and the blackened carcasses

lay in the sheltered spots, some stretched out, others in as natural

a position as if the animals had merely lain down to rest. It was small

wonder that cheerful stockmen were rare objects that spring.

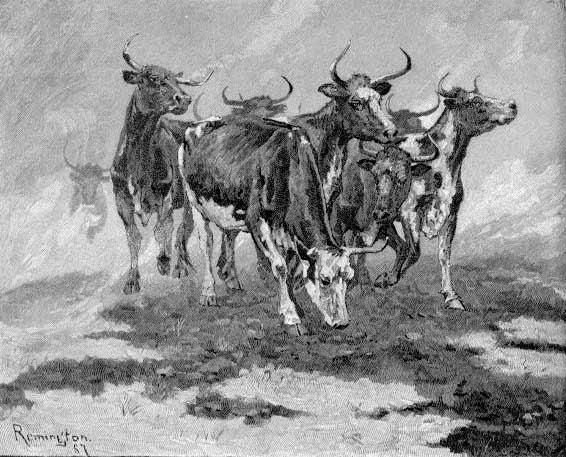

"Drifting Before the Storm," Frederic Remington, Collier's Magazine,

July, 1904

Andy Adams in his 1907 novel Reed Anthony, a Cowman described the impact of the great storm on cattle:

The removed cattle, strangers in a strange land, drifted to the fences

and were cut to the quick by the biting blasts. Early in January the worst

blizzard in the history of the plains swept down from the north, and the

poor wandering cattle were driven to the divides and frozen to death

against the line fences. * * * * [W]e were powerless to

relieve the drifting cattle. The morning after the great storm, with

others, I rode to a south string of fence on a divide, and found thousands

of our cattle huddled against it, many frozen to death, partially through

and hanging on the wire. We cut the fences in order to allow them to drift

on to shelter, but the legs of many of them were so badly frozen that,

when they moved, the skin cracked open and their hoofs dropped off.

Hundreds of young steers were wandering aimlessly around on hoofless

stumps, while their tails cracked and broke like icicles. In angles and

nooks of the fence, hundreds had perished against the wire, their bodies

forming a scaling ladder, permitting late arrivals to walk over the dead

and dying as they passed on with the fury of the storm. I had been a

soldier and seen sad sights, but nothing to compare to this; the moaning of

the cattle freezing to death would have melted a heart of adamant. All we

could do was to cut the fences and let them drift, for to halt was to die;

and when the storm abated one could have walked for miles on the bodies of

dead animals.

"Montana Blizzard," F. Remington.

When the brisk cold wind comes from the north, cattle, like humans, keep their backs to the wind.

Thus, they drift to the south. Cowboy Bob Fudge, observed that in a storm cattle unless they

were halted by a river or line riders, could drift for almost one hundred miles. See Russell, Jim:

Bob Fudge, Texas Trail Driver, Montana--Wyoming

Cowboy, 1862-1933, Big Horn Press, Denver, 1962, p. 73. Fudge at age 12 was the sole support of his

mother and siblings. His father had died of small pox after a disasterous cattle drive in which the

Comanches had stolen the entire family herd and most of the horses.

By age 15, he was trailing cattle north for the notorious John Pinchney "Pink" Calhoun Higgins. Pink reputedly

shot and killed at least 14 men. There may have been more, but Pink lost count. Simply put, Pink was

a good shot and had an aversion to rustlers. Pink's reputation began as a result of the

Horrell-Higgins Feud which began when the Horrell Brothrs allegedly rustled some of

Higgins' cattle. Three of the Horrell brothers ended up dead and the fourth found it expedient to move

to Oregon. Fudge trailed

cattle and rode line for the XIT. Later Fudge established his own ranch on Little Powder River south of

Biddle, Montana. At age 72, the old cowboy, fell and broke his hip. He died in the

hospital at Gillette. Among those attending his funeral were three of his old mess mates

from the trail drives up from Texas.

Drifting Before a Storm ,

Drift fences were constructed to, among other purposes, preclude cattle from wandering too far. Thus, a

drift fence would make a round-up easier. The most famous of the drift fences was

that constructed by the XIT from the New Mexico border all the was across the Panhandle of

Texas. In Wyoming, the Two-Bar constructed one in Goshen Hole. But in the winter,

three or four days before a blizzard would come out of the north, the cattle would start

drifting to the south. This would necessitate cowboys having to ride the line to prevent the

fence from being broken.

Riding Line ,

James Mooney, who became a cowboy at age 13 and trail boss by age 19, explained:

One of the purpose for which the drift fence was builded, was to hold the

herds from drifting into territory beyond the fence. West of that fence was

a rough brush section and when cattle got into it was a pert job to get the

critters out. The drift fence saved work and riders. We could always tell,

two and three days ahead, when a norther was going to hit, because the

cattle began to drift for shelter and by the time the storm hit the herd

would be drifting a-plenty. Before the days of the drift fence, holding the

herd before a coming norther was like trying to stop a preacher from

accepting donations.

Along that drift fence, during that dry spell I saw carcasses laying one

against the other. The critters drifted to the fence and there died.

The drift fence were put up in many sections of the range country. The

ranchmen ranging cattle in a section would jointly pay the cost and the

expense of keeping the fence up. For each 25 miles of fence a rider was

used who did nothing but ride the fence line and fix breaks. He carried a

hammer, pliers, and staples in the saddle bag as his tools for the job.

The cattle rustler, for a spell of time, caused more breaks in the drift

fence then the cattle did. The drift fence was custard pie for the rustler,

just before and during a storm. During such weather critters could be

depended upon to be crowding the fence. The rustler would cut a gap in the

fence through which the critters would drift and stray to hades. The rustler

would watch the critters drift through the fence and then help the animals

on their way.

Our outfit always put on extra fence riders when a norther was headed our

way. As soon as the cattle started drifting the extra riders would go on

and stay untill the storm was over.

With the catching of them two bunches of rustlers, we had this

satisfaction that they did not cut any more fences, unless they did it

in hell.

But a drift fence at a time of a blizzard could have unintended consequences. John Clay wrote of one

blizzard in Wyoming:

"It was the beginning of a three days' blizzard, and such a blizzard! The snow

came driving from all points of the compass. It built up great drifts in the streets

of Cheyenne. It howled wildly around the Stock Growers' National Bank corner [then located on the northwest corner of 17th and

present-day Cary. In 1905, it moved to the northeast corner of 17th and Capitol where the

Wells-Fargo Bank is now located.], and even [R.S.]

Van Tassell, lithe, active and energetic, was scarcely able to make his way from the Nob

Hill of Wyoming's capital to the business part of the city. The weather god was doing his

worst. Out on the plains the shepherds were catching it; the cattleman could do nothing with

his outside stock, but he was busy feeding on the meadows and pastures. The wires, telegraph

and telephone, were down, and the Cheyenne Northern train was stalled somewhere.

The storm on the third day spent its fury. When the clouds rolled by and the sun came out

there was nothing but wreaths on every street corner of Cheyenne. Many of the house walls

were marbled with plastered snow, while from the eaves great icicles hung toward the ground.

It was a weird, melancholy sort of scene. The roar of the storm was past, but the

aftermath was yet to be gleaned.

"The train from the north had got in, bringing direful accounts of the loss and disaster

to stock, so the next morning we started out in it, and, after bucking snow on Pole and

Horse Creeks, we dropped down to Iron Mountain — where the iron horse enters the valley

of the Chug."

In Chugwater,

Clay received the bad news:

"Gordon's ranch on Horse Creek * * * caught thunder.

Two Bars, H's and many other brands were caught in the wire fences,

and there they stood damming up till first one animal fell, then another,

then another; at last there was a pathway for the balance behind. I never saw

such a sight. There are big mounds of cattle, nothing visible but horns, for the snow

had drifted over them, and you are spared meantime the horrible sight of seeing piles

of carcasses. Barbed wire has its abuses as well as its uses, and if you want an object

lesson, ride over to Johnnie Gordon's and see what has taken place." Clay, John:

The Silence of the Sybille, Privately published, 1901.

But ostensible drift fences were used for other purposes. Charles Goodnight and other

Texas cattlemen constructed such a fence along the north portion of their range so that Colorado and Kansas

Cattle would not drift south and share in the Texas grass. In one winter, so many cattle died against the fence, that the

Texas Legislature banned any fencing on public land. The fence was taken down n 1890. Other cattlemen used

ostensible drift fences to prevent others from gaining access to water. The Matadore allegedly used a drift fence

to preclude the Indians from using six miles of their own reservation. See 48 Report of Inidan Commission p. 50 (1917)

"Fall of the Cowboy," Frederic Remington, oil on canvas, 1895.

Remington's The Fall of the Cowboy was used as the last of five illustrations for Owen Wister's

"The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher", Harper's New Monthly Magazine, September 1895. In the article, Wister laments

the passimg of the American cowboy:

They galloped by the side of the older hands, and caught something of the

swing and tradition of the first years. They developed heartiness and

honesty in virtue and in vice alike. Their evil deeds were not of the

sneaking kind, but had always the saving grace of courage. Their code

had no place for the man who steals a pocket-book or stabs in the back.

And what has become of them? Where is this latest outcropping of the Saxon

gone? Except where he lingers in the mountains of New Mexico he has been

dispersed, as the elk, as the buffalo, as all wild animals must inevitably

be dispersed. Three things swept him away -- the exhausting of the virgin

pastures, the coming of the wire fence, and Mr. Armour of Chicago, who set

the price of beef to suit himself. But all this may be summed up in the

word Progress.

The effect of the die-off was such that many eastern investors now withdrew and foreign ranchers simply left. Roosevelt noted:

"For the first time I have been utterly unable to enjoy a visit to my ranch. I shall be glad to get home. In its present

form, stock-raising on the plains is doomed and can hardly outlast the century."

Next Page: Moreton Frewen, Horace Plunket.

|