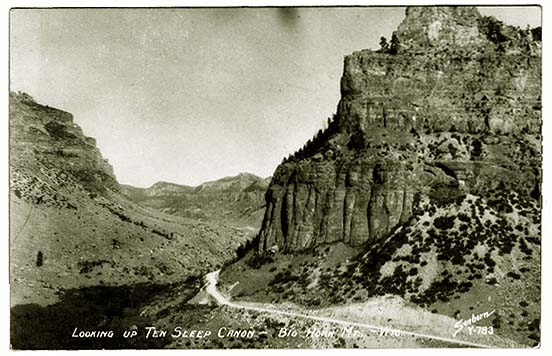

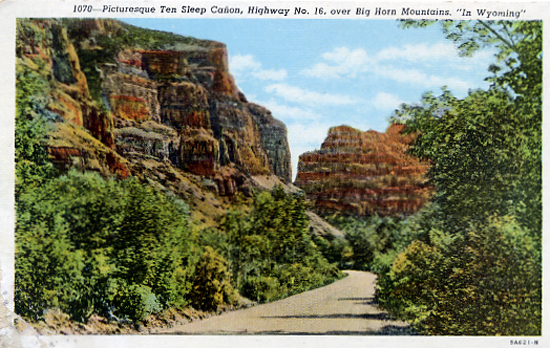

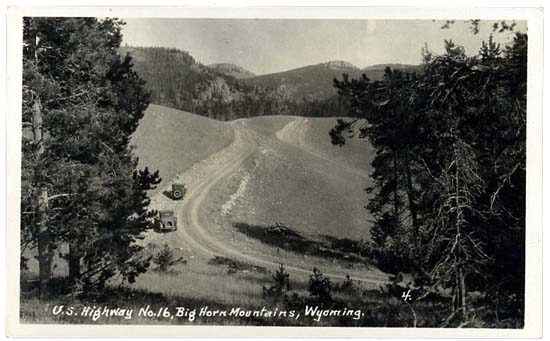

U.S. Highway 16, Ten Sleep Canyon, 1930's. Photo by William P. Sanborn.

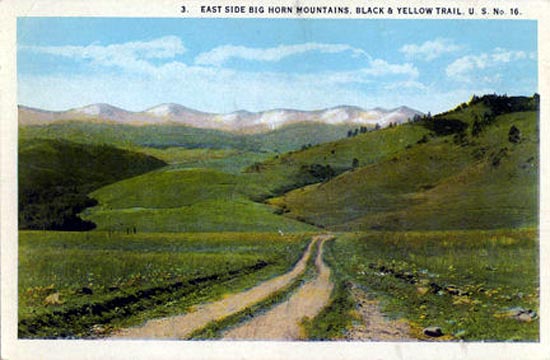

In the 1920's, roads began to be improved in the state.

Promotion began for the Chicago, Black Hills, and Yellowstone Highway, the B and Y Trail. In Wyoming the

B and Y Trail split in the eastern part of the state and followed two seperate routes to Cody, A northerly route

generally followed present-day U.S. Alternate 14 from Cody to Powell, Lovell, Dayton, Spotted Horse, and Gillette.

The southerly route followed present-day U.S. 16 from Cody to Greybull, Ten Sleep, Buffalo, and combined with the more

northerly route at Ucross. Neither road was paved.

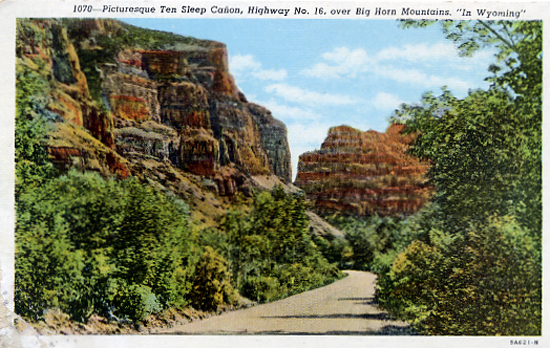

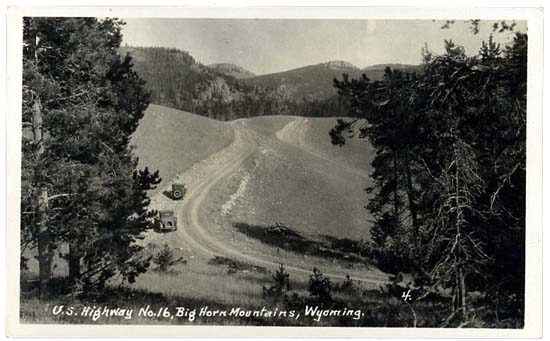

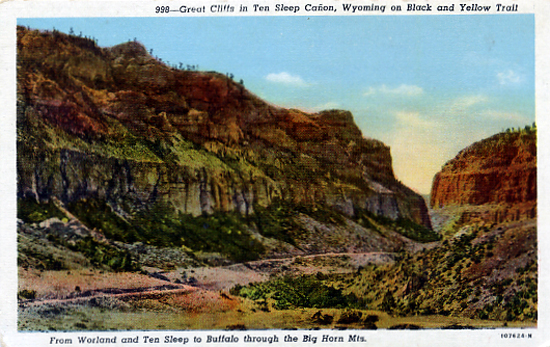

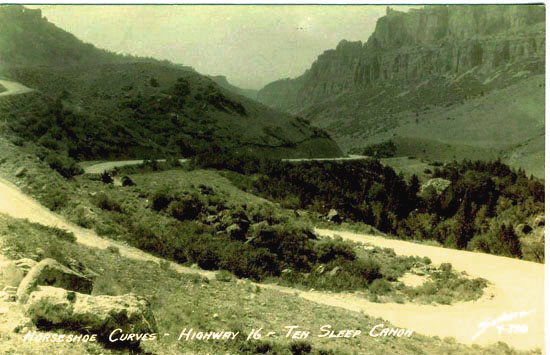

Ten Sleep, Canyon, approx. 1939. Photo by William P. Sanborn.

In the 1920's and 1930's, the graded road east of Ten Sleep was not

for the faint-hearted. From Ten Sleep to Buffalo was 69 miles over Powder River Pass at an elevation of 9677 feet.

The road followed the rugged

and steep Ten Sleep Canyon. For travelers heading east, the gas stations, cafe, and

hotel at the Town of Ten Sleep, were literally a "last chance stop."

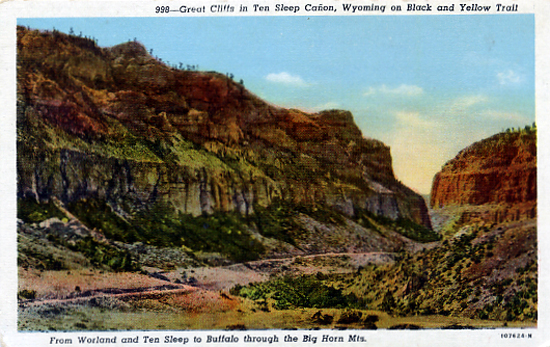

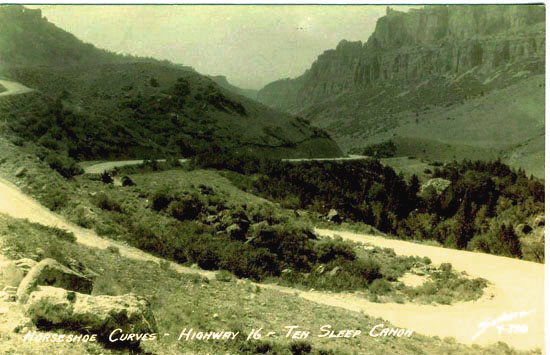

Leigh Creek, Ten Sleep, Canyon, approx. 1939. Photo by William P. Sanborn.

About fifteen miles east of Ten Sleep, just past the confluence of Leigh Creek with Ten Sleep Creek there is a

sharp promontory known as Leigh Creek Vee. On a broad ledge about 200 feet below the

rim of the canyon and about 1,000 feet above the canyon floor is a stone monument topped

with a cross. The monument was constructed in 1889 in the

memory of a British Member of Parliament (member for South Warwickshire), the Honorable Gilbert H. C. Leigh, after whom the creek is named. In 1884,

Leigh, a house guest of Moreton Frewen, lost his

life hunting big horn sheep.

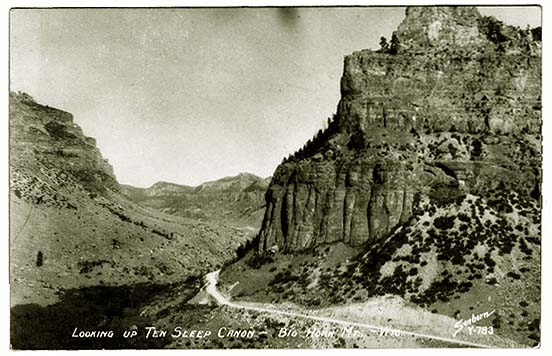

Ten Sleep Canyon, 1936.

The Honorable Gilbert H. C. Leigh went off hunting alone. His body was discovered

five days later on the ledge. It has been speculated that he mistook

the tops of trees adjacent to the top of the canyon as being shrubs into which he

ventured (perhaps reminisent of an incident at a Yale reunion many years later when

Dudley Guilford emerged at 2:00 a.m. from a night of partying at the Reunion Headquarters. The building closed

up behind him. He felt the need to relieve himself. Spying some convenient bushes, he stepped into

the bushes only to discover that the bushes were the tops of trees at the bottom of a ten foot high

retaining wall. He sued Yale, and collected, contending that Yale was negligent; Yale should have

anticipated that one would use the bushes.).

Alternatively, it has been speculated that the Honorable Gilbert H. C. Leigh in an October snow storm rode his horse off the top of the canyon.

Ten Sleep, Canyon, approx. 1936. .

An historical marker alongside the road is somewhat inaccurate referring to

Leigh as a "remittance man." Others have referred to Leigh as a "Lord." He was neither.

As noted above, he was a Member of the House of Commons.

Remittance men were usually younger sons of prominent British families who had

caused an embarrassement to their ever so proper families. Thus, they were sent away to Her Majesty's

dominions beyond the seas on the general condition that they never return. Mark Twain in his 1897

Following the Equator explained:

He was a "remittance man," the first one I had ever seen or heard of.

Passengers explained the term to me. They said that dissipated

ne'er-do-wells belonging to important families in England and Canada

were not cast off by their people while there was any hope of reforming

them, but when that last hope perished at last, the ne'er-do-well was sent

abroad to get him out of the way. He was shipped off with just enough

money in his pocket--no, in the purser's pocket--for the needs of the

voyage--and when he reached his destined port he would find a remittance

awaiting him there. Not a large one, but just enough to keep him a month.

A similar remittance would come monthly thereafter. It was the

remittance-man's custom to pay his month's board and lodging

straightway--a duty which his landlord did not allow him to forget--then

spree away the rest of his money in a single night, then brood and mope

and grieve in idleness till the next remittance came. It is a pathetic life.

We had other remittance-men on board, it was said. At least they said

they were R. M.'s. There were two. But they did not resemble the Canadian;

they lacked his tidiness, and his brains, and his gentlemanly ways, and

his resolute spirit, and his humanities and generosities. One of them was a

lad of nineteen or twenty, and he was a good deal of a ruin, as to clothes,

and morals, and general aspect. He said he was a scion of a ducal house in

England, and had been shipped to Canada for the house's relief, that he had

fallen into trouble there, and was now being shipped to Australia. He said

he had no title. Beyond this remark he was economical of the truth.

[Writer's personal note: The writer's brother is into family genealogy and spends much time, including at

least four trips to the UK, in his quest to uncover the skeletons in the family closet. One day

he inquired, in a whisper over a bottle of beer, whether I knew that a particular ancestor was -- gasp -- a

remittance man.] Many respectable families of Western Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are descended from

remittance men. For further discussion of the background of Gilbert Leigh,

see Cattle Drives.

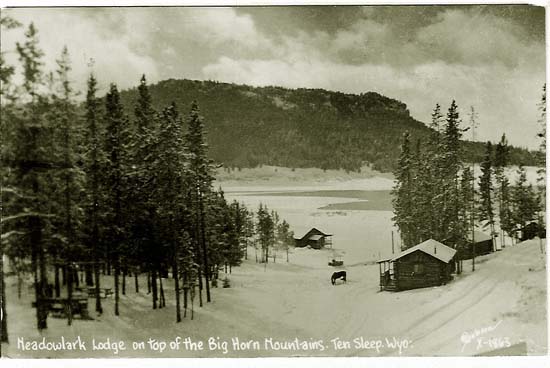

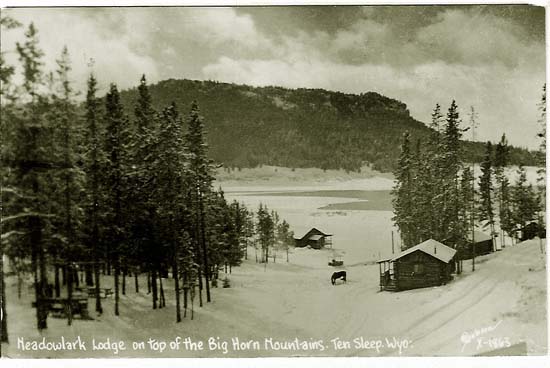

Meadowlark Reservoir, upper end of Ten Sleep Creek, Ten Sleep-Buffalo Highway, approx. 1939. Photo by William P. Sanborn.

In the early years, mail for Ten Sleep came over Powder River Pass from Buffalo.

About 2,500 years ago, Herodotus of Halicarmassus wrote of the couriers of Darius,

"these men will not be hindered from

accomplishing at their best speed the distance

which they have to go, either by snow, or rain, or heat, or by the

darkness of night."

In the Winter, the road from Ten Sleep to Buffalo might be closed for as much as six month a year.

In the 1890's former Confederate teamster Sam Stringer (1830-1905) had the mail contract for

delivery of the mail from Buffalo to Powder River, Sussex, and Ten Sleep. Following the Civil War, Stinger worked as a freighter on the

Bozeman Trail. He was at Fort Kearny at the time of the Fetterman Massacre and helped bury Lt.

Fetterman's company. In the winter, mail was unable to be delivered. About 1892, with Spring, Stinger

set forth from Buffalo with a saddle horse and four pack mules loaded with the accumulated mail pouches.

After twenty-five miles he had to take refuge in an emergency cabin. After supplies gave out, he placed

the mail on a toboggan and strapping on snow shoes he made another push for Ten Sleep.

After 15 miles, one of the snow shoes broke. His own cabin was only about twelve miles away. Thus,

he headed for it, most of the distance crawling on hands and knees. It took five days. After resting at home

and making a new snow shoe, he headed out again, retrieved the mail and in a week finally delivered

the mail to Ten Sleep.

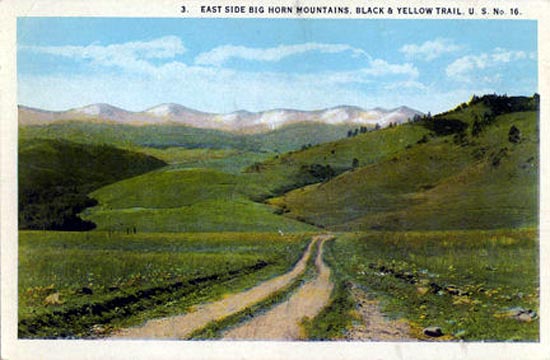

Ten Sleep-Buffalo Highway, U.S. Highway 16, eastside of Big Horn Mountains, approx. 1936.

And even in the late 1920's and early 1930's after designation of the B-Y Trail as a federal highway, the road to Buffalo was less than glorious.

Ten Sleep-Buffalo Highway, U.S. Highway 16, eastside of Big Horn Mountains, late 1920's.

Powder River Pass, U.S. Highway 16, approx. 1939. Photo by William P. Sanborn.

After Powder River Pass, the road turns northward and passes near the headwaters of

Crazy Woman Creek, Muddy Creek and Hesse Creek, the latter named after the foreman for

Moreton Frewen's 76 Ranch, Fred G. S. Hesse (1852-1929). Hesse, noted for his involvement in the

Johnson County War, was an Englishman. He had studied

law in Britain before coming to America. He obtained work as a cowboy in Texas and became

a trail boss for noted contract drover John Slaughter. In addition to being foreman for

Frewen, he previously worked for Sir Horace Plunkett and John Sparks. In 1883, Hesse was the captain of the

largest roundup ever conducted in Wyoming. The 1883 Roundup along Crazy Woman Creek had some 1400 horses, 400 cowboys, and 70 wagons.

U.S. Highway 16, Ten Sleep, Canyon, approx. 1939.

Big Horn Basin continued on next page, Basin. |