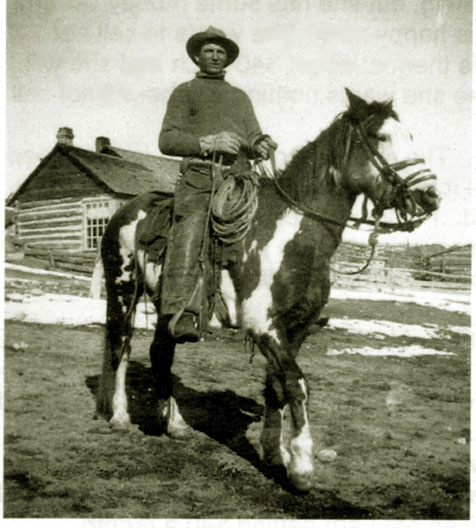

Roundup, approx. 1889

Randall Parrish, the Great Plains, A. C. McClung & Co., Chicago, 1907, wrote:

Life in the great cattle country was a life of variety, yet of sameness. Hardship, loneliness,

peril were the cowboy's constant companions. No weakling long survived, no coward ever endured.

The far north and far south ranges presented different problems for solution, different dangers

to be met, yet over all was a sameness except as to detail. In some places the struggle was

against drought, against the pitiless desert, the arid heat of sun-baked desolation; in others

the battle was as sternly waged against the deadening sleet, the down-sweep of the storm across

the bare Plains. In either case it required men to ride the lines and hold the cattle.

Parrish observed, "From earliest gray of dawn until the flickering twilight, work never

ceased. There were no vacations, no furloughs from this service of the range. Except for

those brief, infrequent periods passed amid the garish glitter of some frontier hell at the

end of the drive to market, the demands of duty seldom ceased."

Perhaps the worst of it was the loneliness: winters in an isolated line camp, life on the trail without newspapers, mail, or news from

home.

LONELINESS

At nights I think of her a heap,

These quiet nights when shadows creep

Down thro' the sage, and ev'ry tree

Looks like a black hearse plume to me.

Oh, lonely land and lonely heart,

It surely seems when I 'm apart

From her I hain't the least excuse

Fer livin', and I sees no use

In even daylight comin', fer

It's always nighttime without her.

Robert V. Carr, 1912 |

On the trail and on round-up, the cowboy suffered from a terrible loneliness, a loneliness illustrated by correspondence from

two cowboys Fred Tucker and George Bacus to Mittie Richardson of Horse Creek, Wyoming. Each had worked on

her father's homestead.

Mittie Richardson and Fred Tucker. Photo and letters courtesy Keith Yeager, Mittie Richardson's great nephew.

The letters also reveal the loneliness of the cowboy and the possiblity that the girl back home might fall for

another. In July, 1903, Fred, then working for the Painter Brothers in Weld County, Colorado, wrote Mittie (puctuation and

spelling as in the original):

My it seems awful lonesome to ride all day and not have a tree to get under or and good water to drink

except you take it with you and worst of all not to have Mittie to talk to, but the

Painters are nice men to work for and I know my pay is good everybody speaks well of them they don't

use tobacco or drink and I havent heard them swear since I have been here so they aint apt to learn me any bad habbets.

Fred was paid $25.00 a month, but, he wrote, "I get my saddle furnished and my bed so I don't have to buy any thing." He hoped that he would have $450.00 saved by

Christmas and if he didn't "it wont be because I blowed it in my love I know that I will be awful lonesome and so

will you but we will have to cheer up and make the best of it for it wont be long." In other letters, he expressed his

lonesomeness and hope that he could see Mittie. In later letters in indicated that he was

making $30.00 a month and hoped to go into the cattle business as there were unbranded calves about.

George Bacus on Bumblebee, Horse Creek, Wyoming. Photo courtesy Keith Yeager.

Prior to working for the Painter Brothers, Fred had worked on the Richardson homestead at Horse Creek. There, he and another cowboy, George Oathanile Bacus, had vied for

Mittie's attention. In 1902, Mittie was sent east to Boston apparently to resolve the situation. In correspondence from family members, it appears that

Mittie's mother did not approve of either George or Fred. Mittie's mother referred to George as

"Backhouse." In one letter, Mittie's mother wrote, "I sat there and looked at Fred while he was eating

dinner and I though of the old saying that love would go where it is sent if it went into a dogs - - - and I just

thought if anybody fell in love with that thing they aught to have him why he can't even talk I was pleasant to him but O dear."

Both Fred and George wrote Mittie while she was in Boston, each expressing their love.

After Mittie's return, in June

1903 things boiled over in the bunk house. Bacus sent Mittie a letter of explanation:

Casper Wyo

June 14, 1903

Miss Mittie Richardson

My Loved One, I sit down to drop you a few lines to let you know that I am on deck yet. I will be

back soon to see my littel love again and se what they do weath me for what I have don. I see now where I was

foolish for leaven Elmer [LaPash, Mittie's brother-in-law] toald me to give up and I am sorry I didnt. I took the horse exptoan [expecting]

to go to town if I could of seen you before I left, I would not have left there. Now Darling, pleas donant let eny

one out side of your folks see this letter I toald ProSiak that I was to blame for

shooting and would not give up, but I gess I well now doant tell Fred I am coming back

I donant want any more trubele weath anyone Darling I would like to have a talk weath you. I was not to

blame for what happened in the bunk house but had not [illegible] of shot atall but I was excited then and could

not help it Well Dear this is cloast to your birth day and I will send you all I can from here that is thre of the pretest fours I can fiend I must

close the tears will not lit me rite eny more best washes to you as ever your Love

G O Bacus

I left Dienannie [The horse Bacus stole in order to make his escape after the shooting]

in the big Louis pasture weath the sadel on hir I hope you have hir by the time that is part of the 0 ranch north of raged top [Ragged Top Mountain, about three miles

west of the Laramie County line between the North Fork of Horse Creek and Horse Creek]

These air sweet for get me nots [forget me nots] it is all I have and hoap they will be recped weath pleasher Hope to see you soon and Mittie when I am in Jale in

Laramie Will you come and see me I would like to tell you all about every thing but can not rite it as I havent time no neather have I go paper this is all I have I will

be back as soon as I can rais money anouff the countey would send for me but I doant want that I will come back weath out thair assistants if they will let me

P S I will be back to hay if thay will let me out in time

In the meantime, Fred, fearing for his life, fled for Denver but wrote reassuring Mittie "As far as my wounds are conserned I am doing fine but I

think I will lay around for a week yet." He had secured a room for one dollar a week and "it is away from the saloon you can rest at ease on that dear."

Ultimately Bacus was arrested and fined $15.00. Fred wrote the sheriff and wanted Bacus re-arrested. Mittie apparently urged Fred to

drop the attempt to have Bacus further punished. Fred wrote assuring Mittie that he would drop the matter but explaining that he was willing to

come to Wyoming and settle it even if it would "cost my life only for your sake * * * I will willingly die for your sake but I hate to be killed by a coward my dear. That beets any thing I ever heard in my life

that he would come to the ranch after tryng to kill me in your site."

After the fine, Bacus left for Nebraska. He and Fred both continued to write Mittie.

Fred assured Mittie that he would write twice a week. Mittie responded to his letters. Her responses to Bacus were apparently cooler, for Bacus noted in one letter,

Now, Dear you neade not be the least bit afraid of me but I no how you feal I will not harm your at tall no matter what comes up you no mittie I think to much of you to see

you un happie if I can do eny thing to make you happy I would be glad to do so." Bacus also expressed loneliness and homesickness. In August he wrote expressing loneliness and inviting Mittie

to go to Frontier Day with him. Again in November, he wrote,

"Mr Dear littel Mittie I will rite you once more as I am so loansym and home sike. I have got a affel bad coald and had to lay off all day and feal like like going to bed but will rite a few lines as

there is a chance to mail it to mirrow this is the woarst place I ever struck."

In the beginning of December, 1903 Fred wrote and asked for Mittie's ring size.

Apparently, however, Mittie's letters to Fred became less frequent. Mittie saved Fred's Letters received up until December 22, 1903. After that date until

until April 27, 1904, Fred continued to write at least twice a week, but only the envelopes were saved. If Fred wrote after that date, the envelopes were not

saved. There was someone else on the horizon.

Mittie Richardson and "Hoot" Jones. Photo courtesy Keith Yeager.

George Bacus also suspected that there was something wrong. On June 14, 1904, Mittie received a letter from Bacus:

Carr Colorado

June 11, 1904

Dear Mittie I will drop you a few lines to let you no where I am but littel I sespose you cair I am sheering sheep at Warns the sheep air fine to sheer I just started 3 days agow and shered 83 head to day and feel like

shering 100 tomirrow I woorked one month for [William H.] Maxwell at Tie siding and when I get dun here I may go back there agan Well you wel soon have a nuther burthday and I dannot get eny thing for you

but you no how I would like to make you a present how is every thing up there now Erik Trout is hering her the weather is fine by by

as ever yours

GO Bacus

address Carr Colorado

In January of 1906, there was one last letter from

Bacus from North Powder, Oregon, in which he begins,

"I shall drop you a few line hoping you we[ll] get it all OK I am very loan sum here weath out herring from you this is the wourst place you ever hear tell of * * * *"

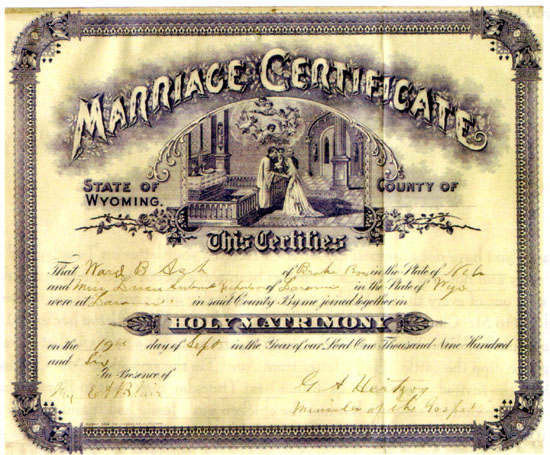

Marriage Certificate for Ward Ash and Mittie Richardson, dated September 19, 1906. Courtesy of

Keith Yeager.

Ward Ash had been a cowboy on the Richardson Ranch. The marriage ended in divorce in 1917. She later married Mathew Pulscher whose parents

were also ranchers from the Horse Creek area. That marriage also ended in divorce, George Bacus ultimately returned to Laramie and married. George died On October 25, 1925, age 48. George's widow,

Catherine, made her living by taking in the elderly and caring for them in her home on 3rd Street, Laramie. Among those she cared for was

a sister of Mattie's who was blind and suffered from epileptic seizures. Upon the sister's death in

1926, George's widow received $5,000.00 from the sister's estate. The 1927 Legislature passed a relief bill for Catherine as

a result of the death of George.

Fred Tucker (1880- ? , originally from Sanilac County, Michigan, apparently returned to Michigan. No record of him is

found in Colorado. Roggen Colorado, lying half way betwenn Fort Morgan and Fort Lupton is now a semi-ghost town, marked by

grain elevators and an abandoned motel. The area now primarily produces grain rather than cattle.

Harry D. "Hoot" Jones (1882-1938), as a result of his ride on C. B. Irwin's famed bronc Silver City in the 1910 Frontier Day celebration, received a moment of fame as as

bronc rider for Gandy's Wild West show in Britain. He returned to Albany County and homesteaded near Centennial, proving up

his claim in 1912. In the 1920's Jones established a dude

ranch, Brooklyn Lodge, which is now on the National Register. A near-by lake is named for his

wife Hattie.

Hoot Jones on Silver City, 1910 Frontier Day. C. B. Irwin on right holding

horse. Moments after the above photo was taken. Silver City broke loose and attempted to trample Irwin.

Irwin suffered injuries to his shoulder.

In 1956, at age 79, Mittie rode round-up for the last time. At the end of

the round-up, she suffered a heart attack, her health declined and she died in December 1957. Next to her grave in Greenhill

Cemetery is the toumbstone of a child who died at age 10 months bearing only the name "Tressie."

Music this page:

Lorena

Words by the Reverend Henry DeL. Webster

Music by Joseph P. Webster

The years creep slowly by, Lorena,

Snow is on the grass again;

The sun's low down the sky, Lorena,

The frost gleams where the flowers have been;

But the heart throbs on as warmly now,

As when the summer days were nigh;

Oh! the sun can never dip so low,

A down affection's cloudless sky.

A hundred months have passed, Lorena,

Since last I held thy hand in mine;

And felt the pulse beat fast, Lorena,

Though mine beat faster far than thine;

A hundred months,'twas flowery May,

When up the hilly slope we climbed,

To watch the dying of the day,

And hear the distant church bells chime.

We loved each other then, Lorena.

More than we ever dared to tell;

And what we might have been, Lorena,

Had but our lovings prospered well

.

But then,'tis past, the years are gone,

I'll not call up their shadowy forms;

I'll say to them, "lost years, sleep on!

Sleep on! Nor heed life's pelting storms."

The story of that past, Lorena,

Alas! I care not to repeat;

They touched some tender chords, Lorena,

They lived, but only lived to cheat.

I would not cause even one regret,

To rankle in your bosom now;

"For if we try we may forget,"

Were words of thine long years ago.

Yes, those were words of thine, Lorena,

They are within my memory yet;

They touched some tender chords, Lorena,

Which thrill and tremble with regret.

'Twas not the woman's heart which spoke,

Thy heart was always true to me;

A duty stern and piercing broke,

The tie that linked my soul with thee.

It matters little now, Lorena,

The past is in the eternal past;

Our hearts will soon lie low, Lorena,

Life's tide is ebbing out so fast.

There is a future, oh, thank God!

Of life this is so small a part,

'Tis dust to dust beneath the sod,

But there, up there, 'tis heart to heart. |

Many of the drovers who came up the Texas Trail were Confederate veterans. During the

war one of the most popular songs with southern soliders was the sad and haunting Lorena about a lost love. The words were

written by The Reverend Henry DeL. Webster. The Rev. Webster's first church was in

Zanesville, Ohio. There, he became engaged to a member of the church choir. The young

lady's family disapproved of her marrying a poor minister and insisted that she break off

the engagement so that she could marry someone with better prospects She did so in a

letter which contained the words, "For if we try we may forget." Those words are repeated at the

end of the fourth stanza.

The Reverend Webster resigned his pastorate and moved to New England. The Reverend Webster's lost love

married a lawyer who later went on to be an Ohio Supreme Court justice. In New England,

the Reverend Webster's words were published in a Boston newspaper. Later, after

the Reverend Webster transferred to a church in Racine, Wisconsin, he granted permission to J. P. Webster (unrelated)

to set the words to music.

Next Page, The end of the big spreads, Moreton Frewen.

|