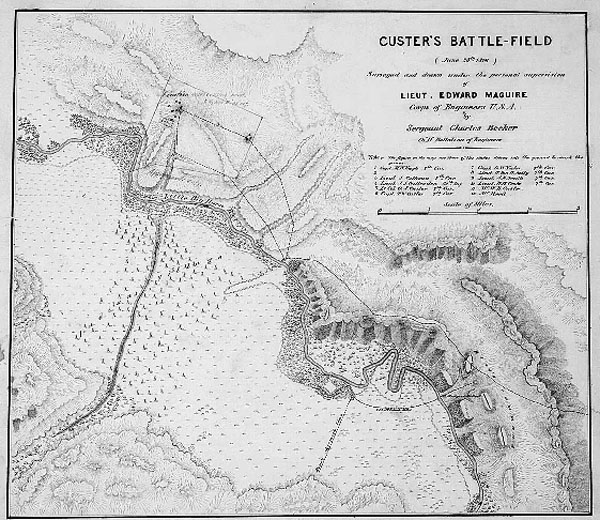

Custer's Battle-Field (June 25th 1876), Surveyed and drawn under

the personel supervision of Lieut. Edward Maguire, Corps of Engineers U.S.A.

by Sergeant Charles Becker Co. "D" Battalion of Engineers.

In 1873, the War Department issued instructions that an engineer was to map every reconnaissance. Thus,

a topographic engineer was included within each of the three main columns

converging on northern Wyoming and southern Montana. Lt. Maguire was

included in Terry's column, but accompanied Col. Gibbon after Terry and

Gibbon separated. The above map was drawn on June 27, while others buried the

bodies of Custer's units. The map was then included in an appendix to Maquire's

annual report and was later published in Mercator's World Magazine.

The bodies of officers were marked by upright stakes or boards reflected in the above

map. See next photo.

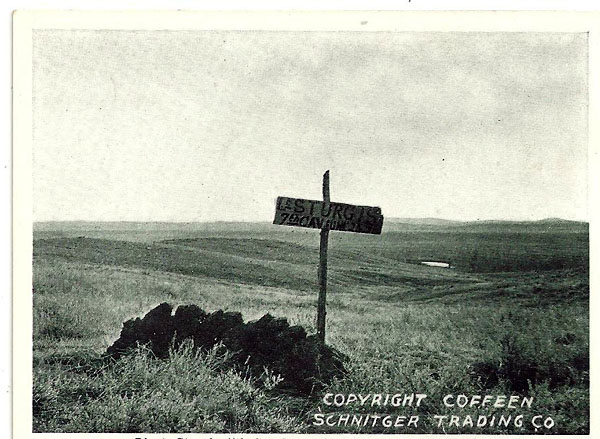

Grave of Lt. J. G. Sturgis, 1877,

photo by Stanley J. Morrow.

Lt. Sturgis was the son of Gen. Samuel Sturgis, after whom Sturgis, S. Dak., is named.

The series of photographs on this and the next page depicting graves and horse bones have

been attributed to both Sheridan stationery store owner Herbert A. Coffeen

(1868-1916), based on a copyright notice, and to Miles City photographer

Laton Alton Huffman (1854-1931). Both sold copies of the photographs.

Coffeen, as will be observed, was 9-years old at the time of the photos and did

not arrive in Wyoming with his parents until the 1880's. Huffman arrived in

Montana in 1878 to be the post photographer at Fort Keogh. The photographs were, in

fact, taken by Yankton, Dakota Territory, photographer Morrow. Morrow (1842-1921)

arrived in Dakota Territory following the Civil War and worked for a period of time

for photographer Orlando Scott Goff. In 1876, Morrow documented Gen. Crook's "horsemeat campaign".

Grave of Unknown, 1877, photo by Stanley J. Morrow.

Reno came upon the Indian encampment, and found himself outnumbered by a host of Sioux to his left

and rear. The horses of two unfortunate troopers bolted and they were carried into

the Indian forces to meet their fate. Thus, Reno and his men were forced to take refuge in a grove of

trees within a bend in the river. There a number of men were killed or wounded including his scout, Bloody Knife,

whose brains splattered onto Reno's face and jacket. Earlier Bloody Knife, an Arikara scout, had foreseen

his own death when he signed to the sun with his hands, "I shall not see you go down

behind the hills tonight."

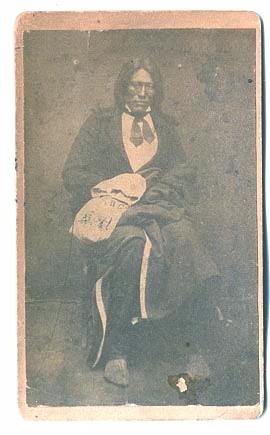

Bloody Knife

Bloody Knife

Bloody Knife was described by Mrs. Custer in her 1885 Boots and Saddles: Or Life in Dakota with General Custer

as her husband's favorite scout. Bloody Knife acted as a guide and scout in Gen. Stanley's

1873 Yellowstone Expedition as well as Custer's 1874 expedition into the Black Hills. Mrs.

Custer recalled in her book:

Bloody Knife was naturally mournful; his face still looked sad when he

put on the presents given him. He was a perfect child about gifts, and the

general studied to bring him something from the East that no other Indian

had. He had proved himself such an invaluable scout to the general that

they often had long interviews. Seated on the grass, the dogs lying about

them, they talked over portions of the country that the general had never

seen, the scout drawing excellent maps in the sand with a pointed stick.

He was sometimes petulant, often moody, and it required the utmost patience

on my husband's part to submit to his humors; but his fidelity and

cleverness made it worth while to yield to his tempers.

Fron the grove, faced with annihilation, Reno was forced to

remount and retreat to some bluffs about a mile away. At the edge of the

trees, Custer's interpreter Isaiah Dorman's horse was killed, falling on Dorman pinning him beneath.

Dorman's remains were later found. They had been singled out for especially

heinous mutulation with body parts amputated and stuffed in his mouth. Not much is known of

Dorman. He was of approximately age 55 and first appeared in 1865 near

Bismark, Dakota Territory, where he was employed as a woodcutter for Durfee and Peck. He was

married to a Sioux to whom he was known as Azinpi. Later he carried

mail and was employed as an interpreter for surveyors for the Northern Pacific.

It is speculated that he may have been an escaped slave, possibly from either

Texas or Louisiana. This is, however, pure speculation based on his last name. In the

organization of the 1876 Campaign, Custer requested his services.

In the retreat, Lonesome Charley Reynold's horse also fell. Reynolds, as was

Dorman, was pinned beneath the horse and was killed. A year later, Philetus W. Norris, Superintendent

of the Yellowstone National Park, had Reynold's remains exumed. Unable to find any relatives of

Reynolds, Norris had Reynolds reinterred in Norris's own family plot in

Detroit. Reynolds and Norris had become friends during the Ludlow expedition to

Yellowstone which Reynolds had guided.

Bloody Knife, 1873 Yellowstone Expedition, photo by William R. Pywell.

William Pywell (1843-1887) was the official photographer for the 1873 Expedition. Before setting

up his own studio in Washington City, he had studied under Alexander Gardner in the

Brady Studios.

In Reno's retreat it was

necessary to ford the river. There, again, Reno's men met a murderous wave of fire. But the

Indians did not follow beyond the river and the remnants of Reno's units found refuge on the

top of what is now known as Reno Hill. Reno in a report on July 5, explained:

I deployed, and, with the Ree scouts on my left, charged down the valley,

driving the Indians with great ease for about two and a half miles.

I, however, soon saw that I was being drawn into some trap, as they would

certainly fight harder, and especially as we were nearing their village,

which was still standing; besides, I could not see Custer or any other

support, [This is a significant statement. Custer had promised Reno that

he would be behind Reno with full support of the "whole outfit." In fact, Custer, as indicated

had gone off on his own.] and at the same time the very earth seemed to grow Indians, and

they were running toward me in swarms, and from all directions. I saw I

must defend myself and give up the attack mounted. This I did. Taking

possession of a front of woods, and which furnished, near its edge, a

shelter for the horses, dismounted and fought them on foot, making

headway through the woods. I soon found myself in the near vicinity of

the village, saw that I was fighting odds of at least five to one, and

that my only hope was to get out of the woods, where I would soon have

been surrounded, and gain some high ground. I accomplished this by mounting

and charging the Indians between me and the bluffs on the opposite side of

the river. In this charge, First Lieut. Donald McIntosh, Second Lieut.

Benjamin H. Hodgson, Seventh Cavalry, and Acting Assistant Surgeon J. M.

De Wolf, were killed.

I succeeded in reaching the top of the bluff, with a loss of three officers

and twenty-nine enlisted men killed and seven wounded.

Reno's retreat across the Little Bighorn. Reno Hill

on the right. Artwork by G. B. Dobson, based on woodcut, Century Magazine, 1892.

Reno's retreat across the Little Bighorn. Reno Hill

on the right. Artwork by G. B. Dobson, based on woodcut, Century Magazine, 1892.

Next page: Custer's battle.

|