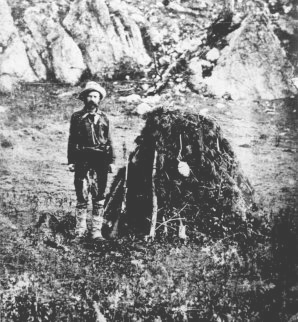

|

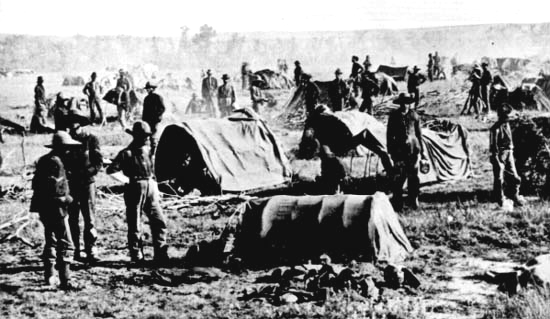

Gen. Crook's headquarters in the field, near Whitewood, S.D., 1876. Photo by Stanley J. Morrow.Note the tents made from the tops of wagons. Following the Battle of the Rosebud, Crook remained in

the area of Goose Creek until early August when Wesley Merritt's arrived. In the meantime,

Crook had sent his wounded from Goose Creek back to Fetterman. Joined by Merritt, Crook resumed the

chase of Indians, leaving his wagons behind and carrying supplies on mule back. Supplies became

scanty resulting in it becoming later became known as the "Horsemeat March," sometimes also referred to as the

"Starvation March." Rain slowed the march. In early September, supplies of

pork, bread, and coffee were exhausted and the troops limited to

small quanties of horsemeat, maybe seven crackers, and two tablespoons of beans. Some would

scavage and dine on antelope and wild onion.

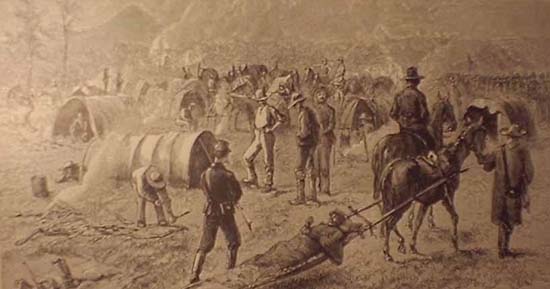

Wounded being removed from field at Slim Buttes. Photo

by Stanley J. Morrow.

On September 9, a foraging party from Crook's units met the Indians at the Battle of Slim Buttes near present day Reva, S. Dak.

There, Chief American Horse was wounded and, not withstanding efforts by army surgeons using Indian

tipis as hospital quarters, died. Thus, the Army had its only victory in 1876.

Army losses included army scout Jonathan "Buffalo Chips" White, a friend of

Wm. F. Cody. Buffalo Chips received his name from 5th Cavalry troopers because of his habit of

closely tailing Cody on Gen. Merritt's campaign along Sage, Rawhide, and War Bonnet Creeks earlier in

1876. See Cody . One soldier was also killed and five were wounded, including Lt. Adolphus H. Von Luettwitz whose leg

had to be amputated.

Wounded being removed by travois

Since the wagons and ambulances were left behind, wounded were removed to Deadwood City by mule-drawn travois or,

as indicated by woodcut lower on page, by litter. The poles for the travois were cut from tipi

poles.

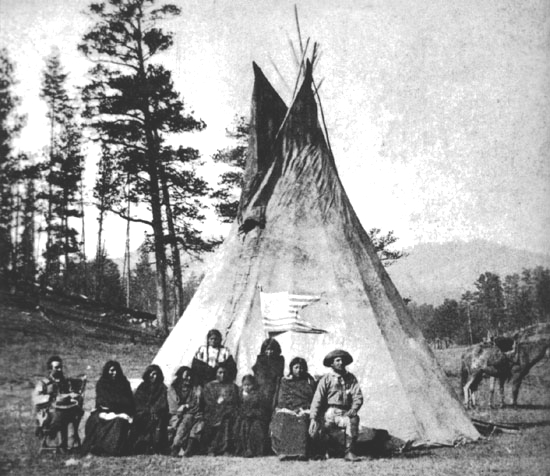

7th Cavalry guidon in front of Indian tipi at

Slim Buttes. Photo by Stanley J. Morrow.

At Slim Buttes artifacts including a 7th Cavalry guidon and Captain Keogh's

gloves were recovered. More importantly, many supplies were captured including

a large supply of meat which Crook's ill and wounded were able to use for sustenance.

The comparitively healthy remained on short rations. Additionally, 110 Indian horses were captured.

Besides American Horse, two Indian women and one child were killed. One Indian boy was

found in the village having slept through the battle. The result was

that it was now the Indians without adequate supplies. Further battles on November 25 were fought with Dull Knive and Wild

Hog on the Red Fork of Powder River and on January 8 at Wolf Mountain. Thus,

it was the threat of starvation ultimately led the Indians and Crazy Horse to surrender to the Army. In

May, Crazy Horse surrendered at Fort Robinson and Sitting Bull crossed the "Medicine Line" over to Canada.

"The Sioux Campaign of General Nelson A. Miles in the Tongue river Region -- An

Indian Attack Upon a Sick Train," Leslie's Illustrated News, 1877

"The Sioux Campaign of General Nelson A. Miles in the Tongue river Region -- An

Indian Attack Upon a Sick Train," Leslie's Illustrated News, 1877

The injury to the individual on the litter

was received in a skirmish between Gen. Miles and Sitting Bull on March 21, 1877.

In Canada, Northwest

Mounted Police Superintendent James Morrow Walsh accompanied by six other men met with Sitting Bull

to inform the Indians that as long as they were in the land of the Great Mother it would be necessary for them

to obey the law as any other citizen. Sitting Bull took the position that the

Sioux, having hunted on both sides of the Medicine Line and having fought for the

British in both the American Revolution and the War of 1812, were British Indians. He displayed to

Superintendent Walsh medals which had been given to his grandfather by George III in recognition of

Sioux services to the Crown. Sitting Bull was also advised that he was

not regarded as a British Indian but an American Indian and would not be provided food or other

annuities.

Both the American and Canadian governments were fearful that Sitting

Bull might resume war on the United States. At the suggestion of the Canadian

government, President Grant ordered Gen. Terry to meet with Sitting Bull and

offer him amnisty should he return to the United States and live on a reservation. On October 17, 1877,

Gen. Terry met at Fort Walsh, Sask. with Sitting Bull and relayed the message of the President.

Terry reported that Sitting Bull made answer:

Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull

For 64 years you have kept me and my people and treated us bad. What have

we done that you should want us to stop? We have done nothing. It is all

the people on your side that have started us to do all these depredations.

We could not go anywhere else, and so we took refuge in this country. It

was on this side of the country we learned to shoot, and that is the reason

why I came back to it again. I would like to know why you came here. In

the first place, I did not give you the country, but you followed me from

one place to another, so I had to leave and come over to this country.

I was born and raised in this country with the Red River Half-Breeds, and

I intend to stop with them. I was raised hand in hand with the Red River

Half Breeds, and we are going over to that part of the country, and that;

is the reason why I have come over here. (Shaking hands with the British

officers.) That is the way I was raised, in the hands of these people here,

and that is the way I intend to be with them. You have got ears, and you

have got eyes to see with them, and you see how I live with these people.

You see me? Here I am! If you think I am a fool you are a bigger fool

than I am. This house is a medicine-house. You come here to tell us lies,

but we don't want to hear them. I don't wish any such language used to me;

that is, to tell me such lies in my great Mother's house. Don't you say two

more words. Go back home where yon came from. This country is mine, and I

intend to stay here, and to raise this country full of grown people. See

these people here. We were raised with them. (Again shaking hands with the

British officers.) That is enough; so no more. You see me shaking hands

with these people.

V. T. McGillycuddy, 1874

V. T. McGillycuddy, 1874

Crazy Horse,

Tasunka Witko, was killed at Fort Robinson, a matter which even this day is subject of

dispute.

Dr. McGillycuddy was the assistant post surgeon at Fort Robinson at the time of the death of

Crazy Horse. Later, he described the death of Crazy Horse:

He was but thirty-six. In him everything was made secondary to patriotism

and love of his people. Modest, fearless, a mystic, a believer in destiny,

and much of a recluse, he was held in veneration and admiration by the

youngest warriors, who would follow him anywhere. These qualities made

him a danger to the government and he become persona non grata to evolution

and to the progress of the white man's civilization, Hence his early death

was preordained. At about eleven p.m. that night in the gloomy old

adjutant's office, as his life was fast ebbing, the bugler on the parade

ground wailed out the lonesome call for Taps, "Lights out, go to sleep!"

It brought back to him the old battles; he struggled to arise, and there

came from his lips his old rallying cry, "A good day to fight, a good day

to die! Brave hearts...." and his voice ceased, the lights went out and

the last sleep came. It was a scene never to be forgotten, an Indian epic.

Purported photos of Crazy Horse, see text below.

Purported photos of Crazy Horse, see text below.

The bayoneting of Crazy Horse by Indian Police is still a matter of dispute; that is,

whether it was murder or was Crazy Horse attempting to escape when he realized that he was to

be a prisoner. McGillycuddy also served as the head of the Pine Ridge Agency in

Dakota Territory where he came into comflict with Red Cloud particularly with

regard to his attempts

to starve the Indians into submission to his plan of sending the children off to

boarding school at Carlisle to become white men and women.

Of greater controversy today, is the issue of whether there are any photographs of

Crazy Horse. It is popularly assumed that there are no known photos of the chief. The photo

to the left was identified by E. A. Brininstool as the only known photo. The photo to the right has

also been identified as the only known photo. The photograph to the right supposedly belonged to the scout Baptiste "Little Bat" Garnier.

It has variously been attributed to have been taken at Ft. Laramie in 1870 or 1872 or at

Ft. Robinson in 1877. Authentication has been based on statements made by

Little Bat Garnier, a man noted for his honesty, and the presence of a scar next to the subject's mouth.

it has been noted that Crazy Horse had visited the Ft. Laramie area at the time

attributed to the photo and that a photographer was present during that period. In contrast,

others have contended that Crazy Horse never in his life permitted a photograph to

be taken, not even on his death bed. It has been noted, that if the photo was taken at Ft. Laramie, Little Bat would have

been a mere teenager, not one with whom the great Lakota war chief would have associated, let

alone done a favor for by permitting a photograph to be taken. Most versions of the

above photo have been cropped so as not to show that it is a full studio tin type. The writer's

personal opinion is that if a photograph were to have been taken of Crazy Horse it would

not have been a full studio photograph conplete with chair, potted plants and

backdrop, all of which, however, are typical of the period. Michael "Bad Hand" Terry, student of the Plains Indians,

frequent lecturer, and Indian reenactor. has also noted in an email to the writer:

The long white shirts, armbands, scarf around neck, large eagle plume from under the main tail and

more importantly,the super long breastplates were just not worn until the 1880s and later.

Following Crazy Horse's death, his parents took his body. It was ultimately buried in an

unknown location possibly near the head of a creek known as Wounded Knee.

Next page: The Nez Perce Campaign.

|