|

View from Reno Hill, circa 1913

View from Reno Hill, circa 1913

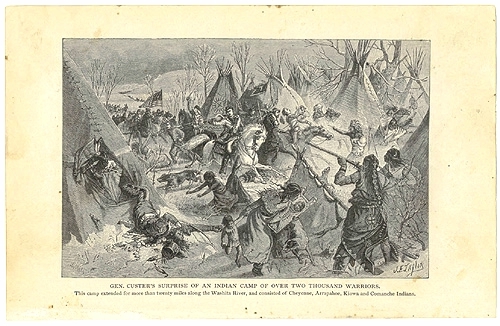

Reno's units were not the first to be left by Custer in the lurch to

find for themselves. Custer at the Battle of Washita, November 27, 1868, had employed tactics similar to that

at Little Bighorn. His victory there resulted in a popular belief that he was

the foremost Indian fighter of the Plains, a belief carefully cultivated by

Custer in books such as his 1874 My Life on the Plains. Benteen later sarcastically referred to the

book as "My Lie on the Plains."

G. A. Custer at the Battle of Washita

At Washita Custer divided

his forces into four and proceeded on his own out of sight of Major Joel Elliott and his men. Elliott was cut off

by the Indians and decimated. Custer, following the battle, withdrew from the area without ascertaining

Elliott's fate. The mutilated bodies of Elliott and his men were found several months

later when the 7th Cavalry returned to the scene. In My Life on the Plains, Custer devotes

two chapters, 10 and 11, congratulating himself on how well he did, dening that he knew where Elliott was,

and but few other words

as to Elliott. Indeed, toward the end of Chapter 11, Custer quotes Gen. Sheridan's

words of adulation:

Special congratulations are tendered to their distinguished commander, Brevet

Major-General George A. Custer, for the efficient and gallant services

rendered, which have characterized the opening of the campaign against

hostile Indians south of the Arkansas.

Custer's apparent abandonment of Elliott is regarded as having caused lasting

dislike by Benteen of Custer. It appears, however, that Benteen's dislike predated

Washita with Benteen regarding Custer as an egotistical blowhard. Benteen later confessed,

"I'm only too proud to say that I despised him." Indeed, a letter by Benteen to William J. DeGresse, severely

critizing Custer was printed in a newspaper. This resulted in Custer's threat to

whip Benteen. Later, on Gen. David S. Stanley's 1873 Expedition to the Yellowstone, Custer relegated Benteen to duty

at an army supply depot for railroad surveyors in eastern Montana Territory.

That winter when Benteen's daughter lay dying at

Fort Rice, Custer refused Benteen leave. But Benteen was not the only one who had problems with

Custer on the expedition. Gen. Stanley (1828-1902) had increasing problems with the

hard-headed Custer. Six times Stanley ordered Custer to get rid of a personal stove. The final

irritant was Custer's taking along an in-law, Fred Calhoun, to act as his publicist. Stanley had Custer arrested for

allowing Calhoun, a civilian, to use a government horse. For two days Custer was relegated to riding at

the rear of the column until, with Custer's roommate at West Point former Confederate Major General Thomas L. Rosser acting as

a mediator, Stanley relented. Not withstanding that the two had fought against each other during

the War, the two remained friends. Indeed, in one campaign Custer succeeded in capturing Rosser's

baggage including a brand new coat of Confederate gray. Rosser being the taller of the two, it

failed to fit Custer. Rosser was on the expedition as the Railroad's chief engineer. Nor did the

Civil War interrupt the feeling of comradeship by Custer with other classmates who joined CSA forces. Indeed,

when Stephen Dodson Ramseur left the Point to join Southern forces, Custer hosted a farewell party at

Benny Havens. Havens establishment was a supplier of

victuals and spirits to cadets, but was off limits. Today it is remembered in the traditional

Point song Benny Havens, Oh! sung to the tune of a old Scottish song The Tulip composed

by James Oswald in 1757.

Benny Havens, Oh!

Come tune your voices comrades, and stand up in a row,

For to singing sentimentally, we are about to go.

In the Army there's sobriety, promotions very slow,

So we'll sigh our reminiscences of Benny Havens, Oh!

Chorus

Oh! Benny Havens, Oh! Oh! Benny Havens, Oh!

We'll sigh our reminiscences of Benny Havens, Oh!

(Repeat three more times)

Benny Havens, Oh! was written by Lucius O'Brien and Ripley A.

Arnold allegedly after a visit sans permissione to Benny Havens. It has been estimated that

over the years more than 60 verses have been added commemorating various officers. The song itself was published in 1855 by

J. Sage & Sons, Buffalo, New York. Thus, the song predates a more famous song set to the same

tune, Wearin' of the Green, written by the Franco-Irish-American playwrite, Dion Boucicault in 1865. Following the

death of O'Brien in the Seminole Wars, Verse XVIII was added to the original song:

XVIIIFrom the land of death and danger--from Tampa's deadly shore,

Comes up the wail of manly grief, O'Brien is no more;

In the land of sun and flowers his head lies pillowed low,

No more he'll sing "Petite Coquille," or "Benny Havens Oh!"

Oh! Benny Havens Oh! Benny Havens Oh!

No more he'll sing "Petite Coquille," or "Benny Havens Oh!"

First Lt. Lucius O'Brien, Co. H. 8th Infantry, now lies with others killed in the

Second Seminole War beneath a pyramid in a small cemetery to

the south of the old St. Augustine [Fla.] Post Headquarters building. And following the death of George Armstrong Custer, another verse was added:

In silence lift your glasses: a meteor flashes out,

So swift to death, brave Custer, amid the battle's shout.

Death called - and crowned, he went to join the friends of long ago,

To the land of Peace, where now he dwells with Benny Havens, oh!

When Ramseur was mortally wounded and captured at Cedar Creek, Custer was one of the Union officers

to rushed to his deathbed side.

Nor was Washita the only time that a unit was abandoned. A year before, in July 1867, Custer was dispatched to

engage Indians out of Ft. Wallace. He was aware that he was to provide

escort to a unit under the command of Lt. Lyman Kidder. Rather than wait for Kidder's arrival, Custer went off on

his own toward Colorado while the Indians were able to ravage the plains of Kansas. Kidder and his

men were massacred. Their stripped and mutilated bodies were found approximately 10 days later. Custer ordered the

bodies to be placed in a mass grave. In his My Life on the Plains Custer described

the scene:

Red Bead, being less disfigured and mutilated than the others, was the

only individual capable of being recognized. Even the clothes of all the

party had been carried away; some of the bodies were lying in beds of ashes,

with partly burned fragments of wood near them, showing that the savages

had put some of them to death by the terrible tortures of fire. The sinews

of the arms and legs had been cut away, the nose of every man hacked off,

and the features otherwise defaced so that it would have been scarcely

possible for even a relative to recognize a single one of the unfortunate

victims. We could not even distinguish the officer from his men. Each body

was pierced by from twenty to fifty arrows, and the arrows were found as

the savage demons had left them, bristling in the bodies. While the details

of that fearful struggle will probably never be known, telling how long and

gallantly this ill-fated little band contended for their lives, yet the

surrounding circumstances of ground, empty cartridge shells, and distance

from where the attack began, satisfied us that Kidder and his men fought

as only brave men fight when the watchword is victory or death.

Kidder was bearing a dispatch from Gen.

Sherman relating to Custer's failure to follow orders.

Discovery of the bodies of Kidder and his men

Custer was court martialed and found guilty of the major charges, including ordering, without trial,

the shooting of three of his own men. He then withheld medical attention.

As to Kidder, Custer contended that he was not aware that there was to

be a second dispatch from Sherman and Kidder's inexperience at following Custer's

trail led to his demise. Among those testifying against

Custer was Benteen. The sentence was suspension, without pay, for a year. After ten months

he was reinstated. But Custer apparently did not learn from the lesson. Gen. Stanley on

one occasion repremanded Custer for going off on his own, marching some 15 miles away from

the main column.

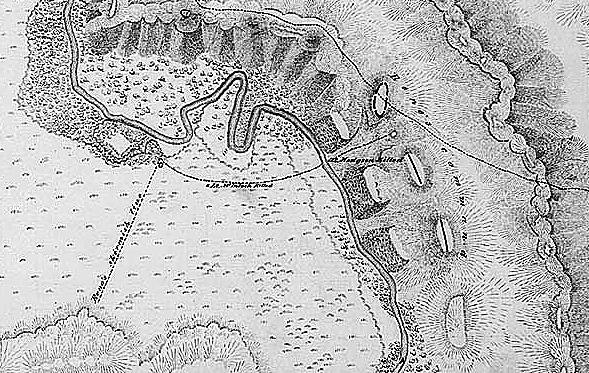

Portion of Maguire Map, showing Reno's movements.

Reno's retreat to the grove, is depicted by the straight line moving upward from the

lower left of the map. The charge across the river is represented by the curved line running to the

east to the hills above the river marked "Reno's Command." Lt. McIntosh is shown as

having been killed in the murderous fording of the river. His

body was found as shown on the map. As will be observed in the next map, the charge

to the hills above the river was straight through Indian lines. As will

also be observed, the force was completely surrounded by Indians. Note, also, the

"route to the water." On top of the bluff troops soon ran out of water in the

hot June sun. A number of the troops volunteers to make the mad dash down the

valley to the water to refill canteens and other vessels as four sharpshooters on the hill above

provided cover. Many who participated received Medals of Honor. Twenty-four

Medals of Honor were issued, including 15 to those who carried water and 4 to the

sharpshooters. One sharpshooter, Charles Windolph was the last survivor of the battle passing

away at age 98 in 1950. Another, Henry W. B. Mechling, named his son Henry Frederick Benteen Mechling.

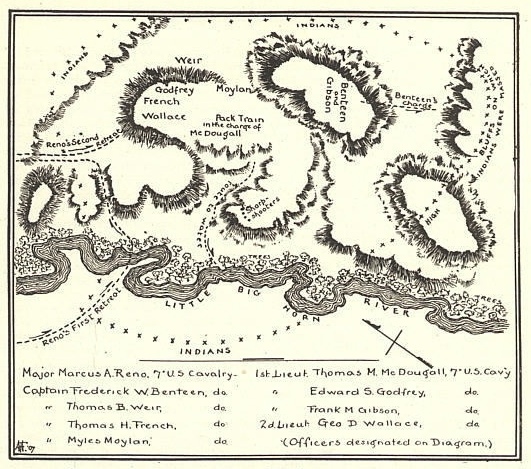

Diagram of the locality of Major Reno's

operations against the Indians, adopted from a sketch made by

1st. Lieut. Edward S. Godfrey.

Godfrey (1843-1932) was a classmate of Maquire in the class of 1867 at West Point. Godfrey received a

Medal of Honor for his leadership against the Nez Perce at Bear Paw Mountain in 1877. Other members

of the class included Arthur Cranston killed in the Modoc Wars in 1873, Jacob Almy murdered by

Apaches at San Carlos in 1873, and Thomas T. Thornburgh killed by Utes in 1879.

West Point Class of 1867

West Point Class of 1867

Benteen, not having found any Indians, returned to the

main party and came across the remnants of Reno's units. Heavy gunfire was heard in the distance, and

Company D was dispatched in the direction of the gunfire. Company D, however, was

repulsed by the Indians about 1 1/2 miles fron Reno's position. Reno was

then joined by Capt. Benteen. The two units, knowing not the fate of Custer, remained beseiged

until late the next day, the 26th. Major Reno, in his report, indicated that

he believed that Custer had been cut off by the Indians and had retreated back to the

Far West.

Music this page, Benny Havens, Oh!

Next page: Custer's battle.

|