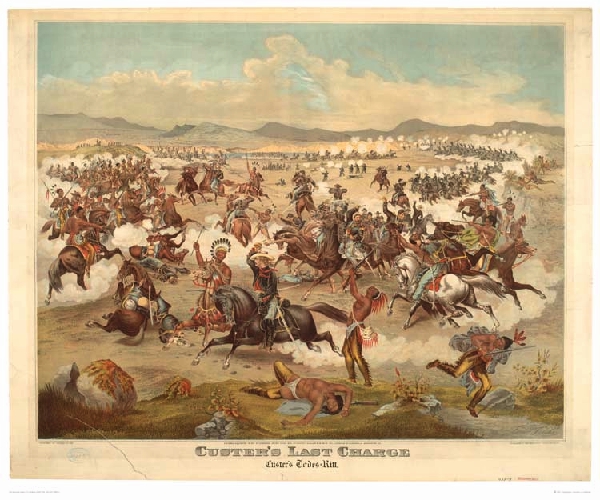

Custer's Last Charge,

Lithograph by [Theodore?] Fuchs, undated

Some question exists as to attribution for the

above lithograph. The first name of the artist has been shown by authories as

both "Theodore," and "Feadore." The only well known illustrator by the name of

Fuchs of the period, however, was

Emil Fuchs (1866-1929) who studied at the Imperial Academy in Vienna and the

Royal Academy, London, before immigrating to the United States in 1905.

Lt. Col. (Brevet Maj. Gen.) George Armstrong Custer.

Lt. Col. (Brevet Maj. Gen.) George Armstrong Custer.

Writers

have put partial blame for Custer's defeat on Crook for not having warned

of the large Indian forces at the Rosebud. See

Fort Fetterman. However, when Terry, Gibbon, and Custer met on June 21, they

had not recieved word of Crook's retreat back to Goose Creek from Rosebud. The failure to

receive such intelligence lay with Custer. As will be observed below,

Gen. Terry instructed Custer to send a scout to Crook. He failed to do so.

Nevertheless, assuredly, Custer was aware of the numbers of Indians. His scouts had

warned him that there were enough Indians to fight many days. A Crow scout, Half-Yellow-Face,

warned Custer, "You and I are both going home today by a road we do not know." Custer with his own eyes using

a spy glass he observed the largest congregation of Indians ever assembled on

the American plains. The plan was for Gibbon, Terry, and Custer's forces to meet on the

26th. As Custer set forth, Terry warned, "Now, Custer, don't be greedy, but wait for us."

Instead, Custer placed emphasis on Terry's official order, writing Mrs. Custer on the 22nd:

I send you an extract from General Terry's official order, knowing how keenly you apprciate words of

commendation and confidence, such as the following: "It is of course impossible to

give you any definite instructions in regard to this movement; and were it

not impossible to do so, the Department Commander places too much

confidence in your zeal, energy, and ability to wish to impose upon you

precise orders, which might hamper your action when nearly in contact with the

enemy."

Custer's extract was, perhaps, taken out of context and did not afford Custer a blank check.

The full text of the order:

Headquarters of the Department of Dakota (In the Field)

Camp at Mouth of Rosebud River, Montana Territory June 22nd, 1876

Lieutenant-Colonel Custer,

7th Calvary

Colonel: The Brigadier-General Commanding directs that, as soon as your

regiment can be made ready for the march, you will proceed up the Rosebud

in pursuit of the Indians whose trail was discovered by Major Reno a few

days since. It is, impossible to give you any definite instructions in

regard to this movement, and were it not impossible to do so the Department

Commander places too much confidence in your zeal, energy, and ability to

wish to impose upon you precise orders which might hamper your action when

nearly in contact with the enemy. He will, however, indicate to you his own

views of what your action should be, and he desires that you should conform

to them unless you shall see sufficient reason for departing from them. He

thinks that you should proceed up the Rosebud until you ascertain

definitely the direction in which the trail above spoken of leads. Should

it be found (as it appears almost certain that it will be found) to turn

towards the Little Bighorn, he thinks that you should still proceed

southward, perhaps as far as the headwaters of the Tongue, and then turn

toward the Little Horn, feeling constantly, however, to your left, so as

to preclude the escape of the Indians passing around your left flank.

The column of Colonel Gibbon is now in motion for the mouth of the

Big Horn. As soon as it reaches that point will cross the Yellowstone

and move up at least as far as the forks of the Big and Little Horns. Of

course its future movements must be controlled by circumstances as they

arise, but it is hoped that the Indians, if upon the Little Horn, may be

so nearly inclosed by the two columns that their escape will be impossible.

The Department Commander desires that on your way up the Rosebud you

should thoroughly examine the upper part of Tullock's Creek, and that you

should endeavor to send a scout through to Colonel Gibbon's command.

The supply-steamer will be pushed up the Big Horn as far as the forks

of the river is found to be navigable for that distance, and the Department

Commander, who will accompany the column of Colonel Gibbon, desires you to

report to him there not later than the expiration of the time for which

your troops are rationed, unless in the mean time you receive further

orders.

Very respectfully, Your obedient servant,

E. W. Smith, Captain, 18th Infantry A. A. J. G.

Custer's letter did little to assuage Libby Custer's fears. When Custer's forces departed

from Ft. Abraham Lincoln, Mrs. Custer rode with her husband a distance. In her

1885 "Boots and Saddles" or Life in Dakota with General Custer, she

described the line of troops, horses and wagons marching

off as the band played The Girl I Left Behind Me. A mirage formed in which the procession appeared in air halfway

between Heaven and Earth until it disappeared into the morning mists.

Edward S. Godfrey

Edward S. Godfrey

On the 22nd, a change of attitude on the part of Custer became apparent to some of his

officers. Edward Godfrey later wrote that Custer explained to his officers

his rationale for refusing Terry's offer of extra units from the Second

Cavalry and Gatling guns. Godfrey continued:

This "talk" of his, as we called it, was considered at the time as

somethng extraordinary for General Custer, for it was not his habit to

unbosom himself to his officers. In it he showed a lack of self-confidence,

a reliance on somebody else; there was an indefinable something that was not

Custer. He manner and tone, usually brusque and aggressive, or somewhat

rasping, was on this occasion conciliating and subdued. There was something akin to an

appeal, as if depressed, that made a deep impression on all present. We

compared watches to get the official time, and separated to attend to our

various duties, Lieutenants McIntosh, Wallace, and myself walked to our bivouac for

some distance in silance, when Wallace remarked: "Godfrey, I believe Custer is

going to be killed."

Wallace survived the seige on Reno's Hill, but was

later killed at Wounded Knee.

On the 24th, Custer's units camped at the site of an earlier Indian encampment. It was

Custer's habit to have his personal standard placed outside his tent. Godfrey

wrote that following an officers' call:

[A] stiff southerly breeze was blowing; as we were about to

separate, the General's headquarters flag was blown down, falling toward our rear. Being

near the flag, I picked it up and stuck the staff in the ground, but it fell again to

the rear. I then bored the staff into the ground where it would have the

support of a sage-bush.

Godfrey recalled that another nearby officer later remarked that he regarded the standard falling

to the rear as a bad omen, and felt sure the unit would suffer a defeat.

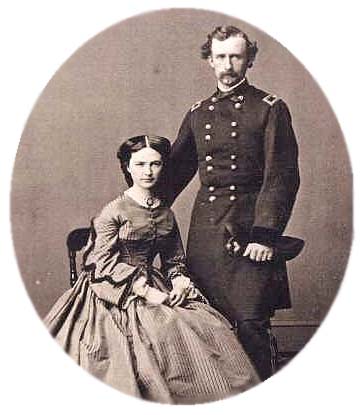

George A. Custer and Elizabeth B. Custer

George A. Custer and Elizabeth B. Custer On June 25, while unbeknowst to them the

battle was ensuing, wives of many of the officers gathered in the Custer quarters. Mrs.

Custer later wrote:

On Sunday afternoon, the 25th of June, our little group of saddened women,

borne down with one common weight of anxiety, sought solace in gathering

together in our house. We tried to find some slight surcease from trouble

in the old hymns: some of them dated back to our childhood's days, when our

mothers rocked us to sleep to their soothing strains. I remember the grief

with which one fair young wife threw herself on the carpet and pillowed her

head in the lap of a tender friend. Another sat dejected at the piano, and

struck soft chords that melted into the notes of the voices. All were

absorbed in the same thoughts, and their eyes were filled with far-away

visions and longings. Indescribable yearning for the absent, and untold

terror for their safety, engrossed each heart. The words of the hymn,

"E'en though a cross it be,

Nearer, my God, to Thee,"

came forth with almost a sob from every throat.

At that very hour the fears that our tortured minds had portrayed in

imagination were realities, and the souls of those we thought upon were

ascending to meet their Maker.

Officers and wives at Ft. Lincoln, 1873.

Custer standing, without hat, Mrs. Custer standing on bottom step on left.

Photo by Orlando Scott Goff.

Orlando Scott Goff (1843-1916) in the 1860's maintained a photography studio in

Yankton, Dakota Territory. In the early 1870's he was the post

photographer at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Later he worked as a traveling

photographer across Dakota, Montana, and Idaho Territories.

Mrs. Custer's premonotion was not the only one. Sitting Bull had a dream in which

he observed soldiers falling upside-down fron the sky. He took it as a favorable

omen.

And on the same afternoon as the wives were singing Nearer, My God, To Thee, General

George Crook and his officers, having retreated from the Rosebud, were enjoying an

afternoon of hunting in the foothills of the Bighorns near present day Sheridan. One of

their scouts, Frank Grouard known to the Brulé as "One-Who-Catches" and to the Lakota as

"Standing Bear, acted as guide. There, in the distance, he later wrote, Grouard

saw the smoke from signal fires indicating that Custer's command was then

engaged, outnumbered, and being badly pressed. The officers using their

field glasses made no import from the smoke and laughed at the idea that

a half-Indian could have such knowledge. But Grouard was not the only one who sensed something was amiss.

Gen. Crook's mess cook, George H. Boswell, in 1924 related to Thomas Julian

Bryant that on the afternoon of June 25, the sound of gunfire could be distinctly heard in the distance. See Annals of

Wyoming, 3:3 at pp 184-185.

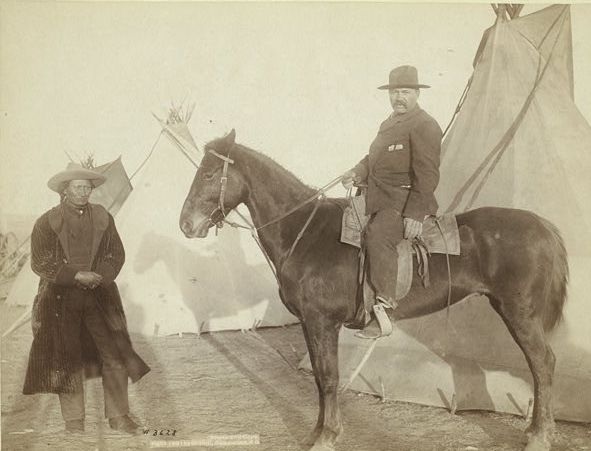

Rocky Bear and Frank Grouard, 1891, photo by

John C. H. Grabill

[Writer's note: Grouard at age 19 was captured by Sioux and spent the next 6 or

7 years in the camps of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. He was adopted as a

brother by Sitting Bull. Grouard was instrumental

in the surrender of Crazy Horse and has been blamed by some as being instrumental

in the subsequent death of Crazy Horse. Some question exists as to Grouard's

ancestry. Many writers claim that he was African-American, the son of the early Black

American Fur Company mountainman John Brazeau. By 1833, Brazeau operated

a trading post on the Yellowstone known as "Braseau's Houses" and married a

Sioux. Grouard, himself, claimed to be partial

Hawaiian, a claim which at the time was greated with considerable skepticism. Truth, however,

can sometimes be stranger than fiction. In 1846, Benjamin P. Grouard went on Mission to the

Tuamotu Islands, today a part of French Oceana and remembered as the landing site for

Thor Heyerdahl's Kon Tiki. After several years, the elder Grouard returned to

California bringing with him a Polynesian wife and three children. Interestingly, 30 years later

more missionaries arrived in the Tuamotu Islands and discovered that some of the natives still remembered

Grouard and his teachings relating to the Prophet Joseph. After a year in

California, Grouard's wife returned to the South Pacific with two of the children, leaving

Benjamin with the middle child Frank. Benjamin then turned the child over to

fellow Mormon missionaries, Addison Pratt and Louisa Pratt, for care. Grouard was excommunicated

from the Church as a result of doctrinal differences. The Pratt's emigrated to

Utah, taking with them the young Grouard. Grouard ran away. The elder Grouard ultimately remarried and

started another family. He, however, despaired of ever seeing Frank again. In

1893, Frank Grouard had become famous, and the elder Grouard read of the publication

of a biography of the scout. Benjamin then travelled to Sheridan where Benjamin immediately

recognized his son, notwithstanding a forty-year separation.

Grouard had little use for Col. Cody who had business interests in Sheridan. One time, the

two almost came to blows in the Sheridan Inn when Col. Cody was repeating his story of having killed

Yellow Hand. Grouard told Cody, "You are nothing but a picture book scout and a picture book showman. That's all you

ever were and that's all you ever will be." Frackelton, p. 109.]

Frederick W. Benteen

Frederick W. Benteen

On the 22nd, Custer and Terry's forces separated. On the 23rd, the troops covered

35 miles. On the same day Crook and his men were near present day Big Horn City, south of present day

Sheridan. On the 24th, Custer covered 45 miles, and after dark another 10.

With the pace, the troops and the horses were exhausted. It was not unusual for

Custer to engage in brutal forced marches. Indeed, he was referred to by some of his men as

"Iron Butt." On the morning of the 25th, the coffee made from bad water was undrinkable. Indeed, the

water was so bad the horses would not drink.

About noon, Captain Frederick W. Benteen was instructed by Custer to

scout out to the southwest along the the foot of Wolf Mountain. Benteen later testified that

this order was senseless since the main Indian trail led off in another direction. About 2:00

p.m. a small force of Indians was spotted and Major Marcus A. Reno was instructed to give chase. As to

this order Benteen testified that Custer did not make clear to Reno the purpose of the order.

Thus, Custer's forces were divided into three. As Reno gave pursuit, Custer moved on. Allegedly, the

last sight of Custer was on a distant ridge waving.

Music this Page:

The Girl I left Behind Me

The hours sad I left a maid

A lingering farewell taking

Whose sighs and tears my steps delayed.

I thought her heart was breaking.

In hurried words her name I blest.

I breathed the vows that bind me;

And to my heart in anguish pressed

The girl I left behind me

Then to the east we bore away

To win a name in story.

And there where dawns the sun of day,

There dawned our sun of glory,

The place in my sight,

When in the host assigned me,

I shared the glory of that fight,

Sweet girl I left behind me

Though many a name our banner bore

Of former deeds of daring,

But they were of the day of yore

In which we had no sharing.

But now our laurels freshly won

With the old one shall entwine me,

Singing worthy of our size each son,

Sweet girl I left behind me

The hope of final victory

Within my bosom burning

Is mingling with sweet thoughts of thee

And of my fond returning.

But should I n'eer return again,

Still with thy love I'll bind me.

Dishonour's breath shall never stain

The name I leave behind me.

Next page: Reno and Benteen's Fight.

|