Battle of the Little Big Horn, painting by Kicking Bear, 1898.

Kicking Bear, Mato Wanahkaka (c. 1846-1904), painted the above at the request of

Frederic Remmington. To the left, in buckskin is Custer. The very faint, ghost-like figures in the upper left, behind the

figures of dead soldiers, are the spirits of the dead. In the center are the figures of

Sitting Bull, Rain-in-the-Face, Crazy Horse, and Kicking Bear.

In 1890, Kicking Bear preached the cause of the Ghost-Dance religion and was imprisoned. He was released in

order to perform in Wm. F. Cody's Wild West show. After traveling with the show to

the United Kingdom, he returned to Pine Ridge. As indicated in the following,

Kicking Bear's painting was not the only Native American rendition of the battle.

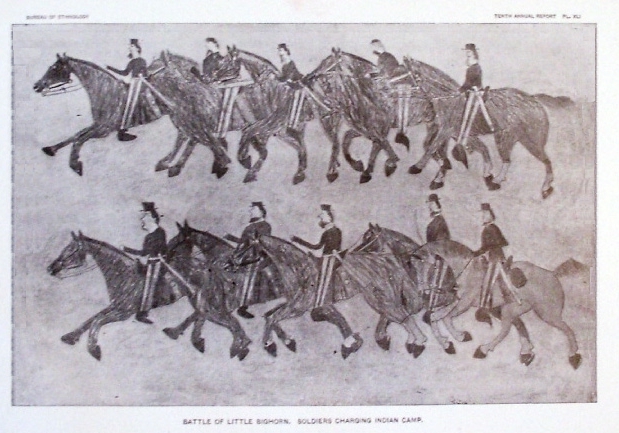

Soldiers charging Indian Village, Bureau of Ethnology, 1888

By July 24, the army had learned from Sioux who had participated in the battle the Indian version. On July 24,

Capt. J. L. Poland wrote a report outlining the events from the Indian perspective. Poland

describes Reno's attack on the village:

The Indian account follows: The hostile were celebrating their greatest of religious festivals - the

Sun dance - when rumors brought news of the approach of cavalry. The dance was suspended

and a general rush, mistaken by Custer, perhaps, for a retreat - for horses

equipment and arrows followed. Major Reno first attacked the village at the

south end and across the Little BigHorn. Their narrative of Reno's operations

coincide with the published accounts how his men were quickly confronted,

surrounded, how he dismounted, rallied on the timber, remounted and cut his

way back over the ford and up the bluffs suffering considerable loss, and the

continuation of the fight for some little time, when runners arrived from the north of the village,

or camp with the news that the cavalry had attacked the north end of the river, three or four miles

distance.

The Indians about Reno had not before this shown the slightest

integration of fighting at any other

point. A force large enough to prevent Reno from assuming the offensive was

left and the remaining available force flew to the other end of the camp

where finding the Indians there successfully driving Custer before them * * * *

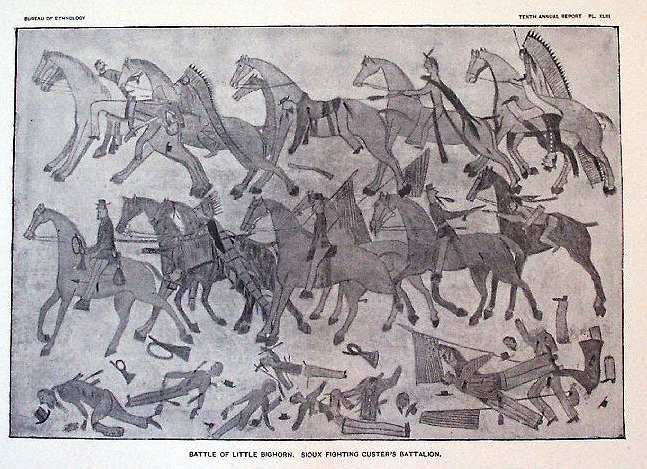

Indians Battle Custer, Bureau of Ethnology, 1888

Captain Poland continues with his report and describes the battle with

Custer:

[I]nstead of uniting with them they separated into ten parties and moved

around the flanks of his cavalry. They report that he crossed the river but only

succeeded in reaching the

edge of the Indian camp. After he was driven to the bluffs the fight lasted

perhaps an hour. Indians

have no hours of the day, and the time cannot be given approximately.

They report that a small number of cavalry broke through the line of Indians in their rear escaped,

but was overtaken, within a distance of five or six miles and killed. I infer from this that this body of retreating cavalry was probably led by the missing officers and that they tried to escape only after

Custer fell.

The last man that was killed by two sons of a Santee Indian "Red Top" whom was a leader in the Minnesota massacre of '62 and '63.

After the battle the squaws entered the field to plunder and mutilate the dead.

The Attack upon Reno and Benteen's position on the bluffs is renewed:

A general rejoicing was indulged in and a distribution of arms and ammunition hurriedly made.

Then the attack on Major Reno was vigorously renewed.

Up to this attack the Indians had lost comparatively few men, but now they say their most

serious loss took place. They give no ideal of numbers but say there was a great great many.

Sitting Bull was neither killed nor personally engaged in the fight. He remained in the counsel

tent directing operations. Crazy Horse (with a large band) and Black Moon were the principal leaders

on the 20th June. Kill Eagle, Chief of the Blackfeet at the head of some twenty lodges left the

agency about the last of May. He was prominently engaged in the battle of June 25 and afterwards

upbraided Sitting Bull for not taking an active personal part in the engagement.

* * * *

The Indians were not all engaged at one time, he says reserves were held to replace loses and

renew attacks unsuccessfully. The fight continued until the end of day when runners,

kept on the look out for other units reported a great body of troops (General Terry's column) advancing up the river.

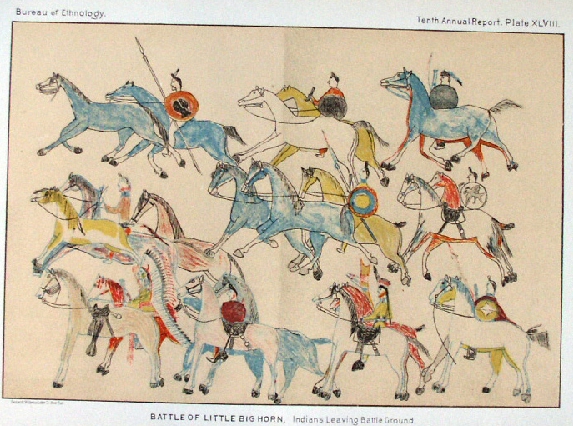

Indians leaving following the battle. Bureau of Ethnology, 1888.

Captain Poland continues his report:

Lodges having been previously prepared for a move retreated in a southerly direction followed

towards and along the base of the mountains. They marched about fifty miles, went into camp

and held a consultation where it was determined to send to all the agencies reports of this success

and to call upon them to come out and share the glories that were expected in the future. Therefore

we may expect an influx of overbearing and imprudent Indians to wage by force perhaps, a

succession to Sitting Bulls demands.

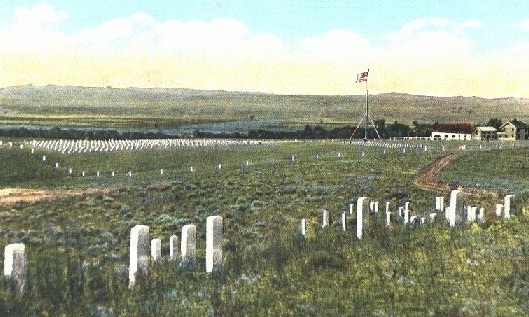

Graves, Little Bighorn Battlefield

At first Custer's men were buried where they fell, graves marked with wooden stakes. The following year the

officers were exumed and reburied at military installations with markers where the men fell. Custer was

returned to West Point. Most enlisted men were reburied in a mass grave.

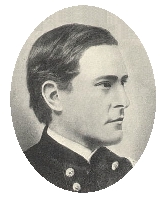

Marcus Reno

Marcus Reno

Questions have been raised as to whether circumstances might have been different had Benteen, Reno, or

Crook promptly acted. Thus, Fred A. Hunt in a 1905 article in the Pacific Monthly, A

Purposeful Picnic -- A Review of Reno's Recalcitrance and the Resumption of

the Route," suggested that had Crook believed Grouard and promply moved northward he might have

saved the day. The suggestion, on reflection, does not work. A military force

cannot move as rapidly as a single rider. Grouard arrived after the battle was long

over.

Hunt also suggested that Reno could have massed his men and, thus, attacked one end of

the Indian village as Custer was attacking the other end. This ignores that

Reno had already been repulsed and placed on the defensive by the Sioux and

Lakota. Reno, of course, makes a good scapegoat. He was later court martialed for

cowardice, but found not guilty, in retreating from the trees. Later he was

court martialed for making improper advances to, and then denigrating, the

wife of an officer. Found guilty, the finding was suspended by the Secretary of War.

He military career ended at a third court martial for being involved in a

drunken brawl and being a peeping tom. It should also be noted that

Benteen's career ended on accusations of alcoholism.

Had Reno stayed in the trees or had he continued on the attack in the village, assuredly,

we would remember Reno as a hero. We would probably admire a marble column erected in his

and his men's memory. We would then debate as to whether Custer could have saved Reno. Did Reno panic as some writers have contended?

Was he derelict in retreating? The testimony of Lieut. Winfield S. Edgerley at Reno's Court Martial is

instructive:

When he first got up on the hill he was excited, but not enough to impair his

efficiency or discourage the men; there was no need of many orders, and he did all that

was necessary; it was plain to the officers what aught to be done; afterwards he was

cool, and the position selected was the best possible within a radius of many miles.

Was Reno drunk as charged at the court martial by two of his packers? Benteen, no great admirer of

Reno, testified that Reno was not drunk nor was he under the influence of liquor at any time.

Frederick William Benteen

Frederick William Benteen

Although Benteen (1834-1898), upon his retirement from the Service, was breveted as a Brigadier General, his career

is almost as tragic as that of Reno. Benteen was from the South. At the beginning of the Civil War his family was

living in St. Louis. As a result of the War, he was estranged from his father. At the

beginning of the War, he announced his intention to enlist in Union forces. His father declared that he

hoped his son would be killed by a Confederate bullet, preferable fired by

a Benteen. Nevertheless, he enlisted. During the war he was responsible for the

capture of a Confederate steamboat upon which his father was serving as an

engineer. While other members of the crew were paroled, the elder Benteen

remained imprisoned.

Of Benteen's children, only one survived to adulthood. His army career effectively ended upon a court martial for

alleged drunkedness in which he was found guilty of three counts. Benteen, himself, felt himself a

failure. Benteen biographer, Charles H. Mills, (Harvest of Barren Regrets: The Army Career of Frederick William Benteen, 1834-1898.

Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Co., 1985) took a line from

Edward Robert, Baron of Lytton's Lucile for the title of

the biography:

The man who seeks one thing in life and but one

May hope to achieve it before life is done;

But he who seeks all things, wherever he goes

Only reaps from the hopes which around him he sows

A harvest of barren regrets. Lucile. Part ii. Canto ii.

Thus, Mills summed up Benteen's life:

There are no monuments to Frederick William Benteen today.

He remains as he lived: a rather obscure supporting actor who

appeared briefly on center stage in a well-known American history

drama and then quietly faded away. It was his misfortune to live

largely unknown and to die largely misunderstood.

The fault for the debacle lay with Custer.

First, at best there was miscommunication with Reno. Reno had

been assured that Custer's units would be in support. They were not. Custer went off on his

own, out of communication with either Reno or Benteen. Since the time of Caesar it has been

recognized that in a coordinated attack, forces must be in communication with each other First, at best there was miscommunication with Reno. Reno had

been assured that Custer's units would be in support. They were not. Custer went off on his

own, out of communication with either Reno or Benteen. Since the time of Caesar it has been

recognized that in a coordinated attack, forces must be in communication with each other

Second, He attacked after being warned

that there were overwhelming forces against him, probably thinking that he would gain

the same victory as he had on Nov. 27, 1868, when he decimated superior forces at the

"Battle" of Washita. There, Custer divided his forces when he attacked the peaceful Cheyenne village of Black Kettle. Next

to Black Kettle's tent flew the stars and stripes. Black Kettle and his wife were killed.

Custer ignored his scouts as to the numbers of Indians present. The night before he camped at a

site which itself indicated the total numbers against him. Godfrey wrote: Second, He attacked after being warned

that there were overwhelming forces against him, probably thinking that he would gain

the same victory as he had on Nov. 27, 1868, when he decimated superior forces at the

"Battle" of Washita. There, Custer divided his forces when he attacked the peaceful Cheyenne village of Black Kettle. Next

to Black Kettle's tent flew the stars and stripes. Black Kettle and his wife were killed.

Custer ignored his scouts as to the numbers of Indians present. The night before he camped at a

site which itself indicated the total numbers against him. Godfrey wrote:

June 24th we passed a great many camping places, all appearing to be of nearly the same strength. One would

naturally suppose these were the successive camping-places of the same village, when in fact they were

the continuous camps of several bands. The fact that they appeared to be of

nearly the same age, that is, having been made at the same time, did not impress us then. We passed

through one much larger than any of the others. The grass for a considerable

distance around it had been cropped close, indicating that large herds had been

grazed there.

An estimate of the total number of Indians who had

left reservations had been prepared and was forwarded by Gen. Sherman. It arrived several days after

the battle.

Third, The division of forces. Had all forces attacked as one, Custer

would probably have prevailed. Other secondary reasons have also been assigned. Thus, Godfrey placed part of the

blame on the weaponry. In many instances the Indians had more modern repeating rifles. Godfrey noted from his own experience that

cartridges when corroded or dirty would not always extract and the cartiriges would have to removed with a

knife. Godfrey, who was with Benteen and thus not present, based on an 1886 conversation with

Chief Gall, blames Reno's retreat from the trees. Benteen was of the opinion that had Reno not retreated, the Indians would

have retired in the face of having to fight both Reno and Custer at the same time. Third, The division of forces. Had all forces attacked as one, Custer

would probably have prevailed. Other secondary reasons have also been assigned. Thus, Godfrey placed part of the

blame on the weaponry. In many instances the Indians had more modern repeating rifles. Godfrey noted from his own experience that

cartridges when corroded or dirty would not always extract and the cartiriges would have to removed with a

knife. Godfrey, who was with Benteen and thus not present, based on an 1886 conversation with

Chief Gall, blames Reno's retreat from the trees. Benteen was of the opinion that had Reno not retreated, the Indians would

have retired in the face of having to fight both Reno and Custer at the same time.

Ultimately, however, blame lay with not waiting until Gibbon's men were to arrive. In a

supplemental report to Gen. Sherman, Terry made the same point:

Ultimately, however, blame lay with not waiting until Gibbon's men were to arrive. In a

supplemental report to Gen. Sherman, Terry made the same point:

Camp on the Yellowstone River, near the mouth of Big Horn, July 2.

I think I owe to myself to put you in more full possession of the

facts of the late operations while at the mouth of the Rosebud.

I submitted my plan to General Gibbon and to General Custer. They

approved it heartily. It was that Custer with his whole regiment should

move to the Rosebud till he should meet a trail which Reno had discovered

a few days before, but that he should not follow it directly to the

Little Big Horn; that he should send scouts over it and keep the main force

further to the south so as to prevent the Indians fromn slipping between himself

and the mountains. He was also to examine the headwater of Talloska Creek

as he passed it and send me word of what he found there. A scout was

furnished him for the purpose of crossing the country to me.

We calculated that it would take Gibbon's column until the 6th to reach

the mouth of the Little Big Horn and that the wide sweep which I had proposed Custer should make would require so much time

that Gibbon would be able to co-operate with him in attacking the Indians that might be found

on that stream.

I asked Custer how long his marches would be. He said they would be first about 30

miles a day. Measurements were made and calculated based on that rate of

progress. I talked with him about his strength, and at one time that perhaps it would

be well for me to take Gibbon's cavalry and go with him.

To this suggestion he replied that without reference to the command he would

prefer his own regiment alone as a homogenous body, for as much could be done with

it as with the two combined, and expressed the utmost confidence that he had

all the force he could need, and I shared his confidence.

The plan adopted was the only one which promised to bring the infantry into action,

and I desired to make sure of things by getting up every available man. I

offered Custer the battery of Gatling guns, but he declined it, saying that

it might embarrass him, that he was strong enough without it.

The movements proposed by Gen. Gibbon's coumn were carried out to the

letter, and had the attack been deferred until it was up, I cannot doubt that we should

have been sucessful.

The Indians had evidently nerved themselves for a stand, but as I learn

from Captain Benton, on the 22d, the cavalry march 12 miles, on the 23d, 25 miles, from 5 A.M.

till 8 P.M., and on the 24th, 45 miles, and then, after night, 10 miles further.

Then, after resting, but without unsaddling, 23 miles to the battlefield.

The proposed route was not taken, but as soon as the trail was struck it was

followed. I cannot learn that any examination of Talloska Creek was

made.

(Signed) A. H. Terry

Major-General Commanding.

Godfrey was of the opinion that had Custer waited, the Indians would have escaped and Custer would

have been blamed.

It is true that

Custer was permitted flexibility, nevertheless, he knew the plan was for Gibbon and his forces to

join up. Custer simply did not wait. Was it a direct violation of orders? Probably not. Incompetent?

Yes.

Next page: Indian Wars Continued, Slim Buttes, Death of Crazy Horse.

|