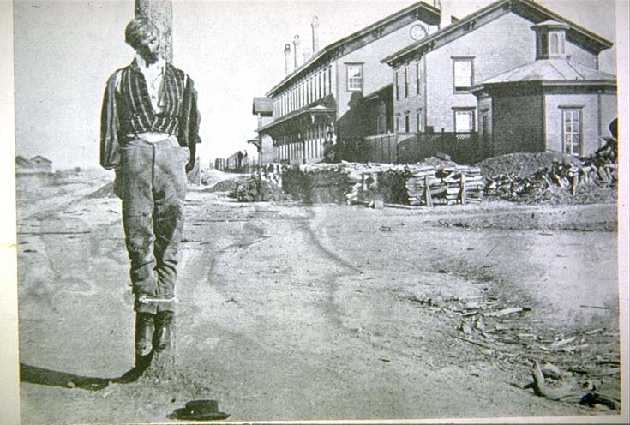

The Hanging of "long Steve" Young, Laramie City, Ocober 28, 1868, photo by Arundel C. Hull.

The above photo shows the Union Pacific Hotel, Eating House, and Depot in Laramie City. Note that

the tracks have not yet been completed. The photographer, Arundel C. Hull (1846-1908),

arrived in Omaha in 1867, spent the next three years taking photographs in

Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah. Hull accompanied William Henry Jackson, on his 1869 journey to

Salt Lake City discussed with regard to Wm. H. Jackson. In

1873, he moved to Fremont, Nebraska.

As noted with regard to the discussion of Sherman on the

next page, as the Union Pacific moved west there were also created instant boom towns at the

end of the line serving the grading crews and providing a "jumping off" spot for

those heading further west. The instant towns were filled with lawless elements.

Thus, the first rector of St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Cheyenne, the Reverend

Joseph W. Cook, noted upon his arrival in

1868:

The activity of the place is surprising, and the wickedness is unimaginable and appalling.

This is a great center for gamblers of all shades, and roughs and troops

of lewd women, and bullwhackers. Almost every other house is a drinking

saloon, gambling house, restaurant or bawdy."

If anything, The Reverend Cook's comments were an understatement. On March 20, 1868, as an example,

the proprietor of a dance house, Charles Martin, shot dead his partner, Andy Harris. The dance house had allegedly

been purchased by the two partners from the proceeds of an armed robbery. Although Martin had

been acquitted by a jury, justice was served by men in black masks removing him from

the Keystone Dance Hall on 17th Street where he had been dancing the night away. The

Cheyenne Argus reported that at the door of the dance hall Martin was seized by four or five men and dragged into

the middle of the road. The men then shut the door of the dance house and the persons

inside, including a policeman, were prevented from getting out. Martin's body was found dangling from a crude gallows at present day 300 E. 17th Street.

He apparently strangled to death as the rope was only two feet long. The Argus noted:

Charles Martin was originally from Lexington, Mo., where his family is well connected, and where he has left a

wife and two children. He career on the plains first commenced as wagonmaster for

Russell, Major & Waddell, and until the last eighteen months or two years, he always pursued that

business. Lately, he had fallen completely into evil ways, spending his time in gambling and

drinking. He also acquired the reputation of a throough desperade, ready to shoot at a

moment's notice. We have not learned that he killed any other

men besides Harris, but last summer at Julesburg he shot at Capt. O'Brien without the slightest provocation,

the ball grazing that gentleman's body. Even those whose nature rebels against

secret, midnight assassination in any shape or form, cannot but be

glad at the country being rid of such a dangerous character.

[Writer's note: Capt. O'Brien, Nickolas J. O'Brien, later Sheriff of Laramie County.]

The same night, two alleged mule thieves met

the same fate behind the Elephant Corral. [writer's note: The Elephant Corral was a freight depot where

freighters could load freight and keep their animals between loads.]

A correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, Jim Chisholm, described Cheyenne:

The wildest roughs from all parts of the country are congregated here, as one may see by

glancing into numerouse dance-houses and gambling hells -- men who carry on the

trade of robbery openly, and would not scruple to kill a man for ten dollars. This class is

decidedly in the majority, and they have carried matters with a high hand for sometime past.

Strangers are beset and robbed, and honest traders leaving the city with their mule

teams are often waylaid and rendered penniless at a moment's warning.

For more on the early days of Cheyenne, see Cheyenne.

Laramie was so bad, that supervision of the town had to be taken over by the

Federal Court. Indeed, in these towns four times as many railroad workers were killed than were

killed by accidents on the right-of-way.

The lawless elements were brought under control by the actions of

Committees of Vigilence. In Laramie City, N. K. Boswell, first sheriff of Albany County and

later deputy United States Marshall and warden of the Territorial Prison, was

reputedly a member of the Committee. In Laramie City, in addition to Young pictured at the top of the page, at least

three other miscreants met their

end at the hands of the Committee, including Asa "Ace" Moore, Con Wagner (a.k.a. Con Moore), and

an individual known as "Big Ned" or "Big Ed" Bernard.

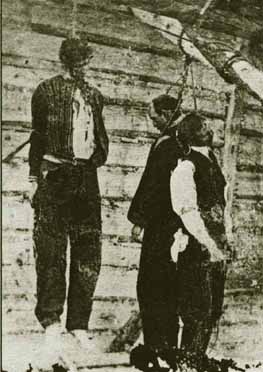

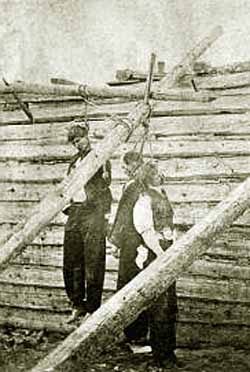

In the early morning hours of October 28, 1868, members of the Committee of Vigilence proceeded to the

Belle of the West, a tent saloon operated by Ace Moore and his half brother Con. The saloon had a reputation for violence and thus

was referred to by locals as the "Bucket of Blood." The term bucket of blood was commonly applied to

any saloon in the west with a violent reputation. Ace and Con with "Long Steve" Young were self appointed

town marshals. The three had been implicated in a number of killings in Laramie City. By October 1868 at least thirteen

men had been killed and another seven died under suspicious circumstances which pointed to

the three." On October 18, a prospector "Hard Luck" Harrison was killed in a gunfight with an

unknown assailant. Most

killings in Laramie City, however, were by garrotting. After a fifteen minute gun battle between the vigilantes and the

denizens of the saloon, Ace, Big Ned, and Con were captured, taken to an

incomplete cabin behind the Frontier Hotel and summarily hanged. In the battle, Charles Barton, a coronet player, was killed and

William Willie, a Union Pacific fireman was mortally wounded. Also wounded was William McPherson.

. . . . . .

Left to Right: "Big Ned" Bernard, Asa Moore, Con Moore

On the way to the unfinished cabin, Big Ned, sometimes referred to as "Big Ed," was silent. At the cabin, he asked if his captors minded if he took off

his boots; he did not want to die with his boots on. Note in the above photos, Big Ned is in his stocking

feet. In the morning with the bodies of the three turning stiff with rigor mortis, Long Steve was politely told that

it was advisable that he leave town. Allegedly, Long Steve's fiancée had reported to N. K. Boswell that Long Steve had

admitted to her that he was the one who killed Hard Luck Harrison. Long Steve declined to leave, reportedly

saying that he wasn't going to let a bunch of stranglers scare him. That, however, proved to be a

mistake. The crime problem in Laramie ended.

The use of Committees of Vigilence might be excused as being brought on by practical necessity. It will

be recalled that in the early years, what is now Wyoming was a part of Dakota Territory. Although justices of

the peace may have been appointed to provide a semblance of due process for minor crimes, they had not

jurisdiction to try felonies such as homicide. The closest court with such jurisdiction was in Yankton about 600 miles away.

Lawyer, John Wesley Clampitt, later observed that efforts to take the accused to Yankton went for naught, they

either escaped or were freed by their comrades. Nor was trial in front of the justice of the peace certain of

result. Clampitt recalled being employed as co-counsel to represent one alleged

murderer in Cheyenne. The defense was to be the lack of jurisdiction of the court to try the

prisoner and, therefore, the prisoner would have to be discharged. The two lawyers agreed to

split the fee of $2,000.00. $2,000.00 in 1867 was a lot of money. Clampitt explained:

The argument

on the jurisdiction of his honor's court was set for the following day,

and the object of the lawyer's visit was to retain me in the case, agreeing

to fairly divide the fee. which was §2,000. This may be considered

a large fee for a small amount of work, but it must be remembered

that in those early days lawyers were scarce and money plentiful

among the class that never worked for a living. Besides, it resolved

itself into a philosophical financial question. If the prisoner should be

discharged from custody, he could, by going upon the road, retrieve his

fortunes in a day, perhaps. If he died he would have no use for

the material money, of a material world. His spirit would soar to

those spiritual realms where all good murderers go! In any event,

therefore, it was best that the money should go into the lawyer's

pockets, and in it went! Of course I should have been untrue to every

professional instinct, had I declined the generous offer of this brother

in the wilderness. I agreed to help him divide the prisoner's fortune.

Unfortunately, Clampitt became seriously ill. After treatment by a physician, Clampitt was late to

the court tent. He arrived just in time to find that his honor had discharged the

prisoner without the necessity of Clampitt's services. Thus, Clampitt received no

part of the fee.

A few of these instant towns, typically division points such as Cheyenne and Laramie, became

permanent cities. Some such as Sherman and Ft. Steele lasted a little longer. And yet others which

consisted little more than tents and a few shanties in which saloon keepers,

gamblers, and soiled doves plied their respective trades, may have lasted only a matter of

months. As the tracks were

extended, the inhabitants of the towns would pack up, load up on wagons and move to

the next town, giving rise to the expression, "Hell on wheels," but perhaps borrowing the

expression from a description of the inhabitants of General Casement's work train.

The worst of these temporary towns was Benton, which became the

Territory's first ghost town.

Jack Morrow (center) seated on barrel, Benton, Wyoming, 1868.

John A. "Jack" Morrow (1832-1876), seated on a barrel in the above photo, was originally a freighter who allegedly got

his grubstake by stealing gunpowder from barrels on a wagon train on which he was the wagon boss. The barrels of

gunpowder when delivered were found to be filled with sand.

With his initial funds, Morrow established a road ranch and trading establishment south of the confluence of the South Platte and North

Platte Rivers. From his seat of operations, he preyed upon travelers by having Indians steal stock which

would then be added to Morrow's herds. The road ranch was a two and 1/2 story log building with associated

corrals and outbuildings. As the railroad progressed westward, Morrow became quite wealthy by selling

railroad ties to the road and furnishing cattle for the annual Indian annuities. Wen railroad construction finally passed him by, he

abandoned the road ranch and moved west. Ultimately, he moved to Omaha where he bought a

magnificent mansion. He was described by Walter H. Rowley, Omaha World-Herald, 1954, as

"a handsome, mustachioed, goateed dandy whose flair for flashy dress came close to Wild Bill Hickok's." Morrow's fortune was soon dissipated

with booze and gambling at Matt Harris's gambling den in Omaha. He was a binge drinker who would when

besotted light his cigars with bank notes.

Morrow's memory lives on in the name of Jack Morrow Hills, Jack Morrow Creek and Jack Morrow

Canyon in northern Sweetwater County.

Benton, 11 miles east of present day Rawlins at UP milepost

672.1, lasted only three months from July to September 1868, and attained a population of 3,000.

The town was three miles from the closest source of water. Thus, there was not much

of a demand for water at ten cents a pail, particularly when "forty-rod" cost only twenty-five cents a

glass. "Forty-rod" is a villainous homemade whiskey warranted to kill at forty rods distance.

The town, itself, was named after Thomas Hart Benton (1782-1858), senator from Missouri, father-in-law of

John C. Fremont, and an avid advocate of western expansion. He early supported

roads, stage lines, the telegraph, and the railroad. In one speech he noted of the

west:

"In some respects, it is a desert - barren of wood -sprinkled with sandy plains - melancholy under the somber aspect of the gloomy

artemisia - and desolate from volcanic rocks, through the chasms

of which plunge the headlong streams. But this desert has its

redeeming points - much water, grass, many oases, mountains capped

with snow, to refresh the air, the land, and the eye - blooming

valleys - a clear sky, pure air, and a supreme salubrity.

It is home of the horse found there wild in all the perfection of his

first nature - beautiful and fleet - fiery and docile - patient,

enduring,. and affectionate. The country that produces such horses must

also produce men, and cattle, and all the other animals; and must have

many beneficient attributes to redeem it from the stigma of desolation."

During the three months of Benton's existence, the town provided an interesting contrast. On one hand, it had

twenty-five saloons and five dance halls. The largest of the saloons was a canvas structure referred to

as the "Big Tent," 100 feet in depth, 40 feet wide, and in back there were canvas cubicles in which nymphs du

pave plied

their trade. Immediately next to the cubicles, a physician had set up shop to cure any

maladies that may have been contracted in the cubicles. Zane Grey in his UPR Trail described the bar:

[I]t had been brought complete from St. Louis * * * . It seemed a huge,

glittering, magnificent monstrosity in that coarse, bare setting.

Wide mirrors, glistening bottles, paintings of nude women, row after

row of polished glasses, a brawny, villainous barkeeper, with three

attendants, all working fast, a line of rough, hoarse men five deep

before the counter--all these things constituted a scene that had the

aspects of a city and yet was redolent with an atmosphere no city ever

knew. The drinkers were not all rough men. There were elegant black-hatted,

frock-coated men of leisure in that line--not directors and commissioners

and traveling guests of the U. P. R., but gentlemen of chance. Gamblers!

Zane Grey continues with the scene at night:

The sun set, the twilight fell, the wind went down, the dust settled, and night mantled Benton. The roar of the day became subdued. It resembled the purr of a gorging hyena. The yellow and glaring torches, the bright lamps, the dim, pale lights behind tent walls, all accentuated the blackness of the night and filled space with shadows, like specters. Benton's streets were full of drunken men, staggering back along the road upon which they had marched in. No woman now showed herself. The darkness seemed a cloak, cruel yet pitiful. It hid the flight of a man running from fear; it softened the sounds of brawling and deadened the pistol-shot. Under its cover soldiers slunk away sobered and ashamed, and murderous bandits waited in ambush, and brawny porters dragged men by the heels, and young gamblers in the flush of success hurried to new games, and broken wanderers sought some place to rest, and a long line of the vicious, of mixed dialect, and of different colors, filed down in the dark to the tents of lust.

Life indoors that night in Benton was monstrous, wonderful, and hideous.

Every saloon was packed, and every dive and room filled with a hoarse, violent mob of furious men: furious with mirth, furious with drink, furious with wildness--insane and lecherous, spilling gold and blood.

The gold that did not flow over the bars went into the greedy hands of the cold, swift gamblers or into the clutching fingers of wild- eyed women. The big gambling-hell had extra lights, extra attendants, extra tables; and there round the great glittering mirror-blazing bar struggled and laughed and shouted a drink-sodden mass of humanity. And all through the rest of the big room groups and knots of men stood and sat around the tables, intent, absorbed, obsessed, listening with strained ears, watching with wild eyes, reaching with shaking hands--only to gasp and throw down their cards and push rolls of gold toward cold-faced gamblers, with a muttered curse. This was the night of golden harvest for the black-garbed, steel-nerved, cold-eyed card-sharps. They knew the brevity of time, and of hour, and of life. In the dancing-halls there was a maddening whirl, an immense and incredible hilarity, a wild fling of unleashed, burly men, an honest drunken spree. But there was also the hideous, red-eyed drunkenness that did not spring from drink; the unveiled passion, the brazen lure, the raw, corrupt, and terrible presence of bad women in absolute license at a wild and baneful hour.

Benjamin Marks

Professional gamblers infested all of the end-of-track towns. In Cheyenne, 19-year old

Ben Marks arrived in 1867, but soon discovered that there was much competition. He hit upon a

profitable solution, he opened a "Dollar Store" in which highly attractive

merchandise was displayed in the window priced at only a dollar. When greed for the very much

underpriced goods sucked customers in, they would be diverted to a game of three-card

monte. In the game, the customers would be stripped of all money and, thus, there was

no danger of the goods actually being sold.

Benjamin Marks

Professional gamblers infested all of the end-of-track towns. In Cheyenne, 19-year old

Ben Marks arrived in 1867, but soon discovered that there was much competition. He hit upon a

profitable solution, he opened a "Dollar Store" in which highly attractive

merchandise was displayed in the window priced at only a dollar. When greed for the very much

underpriced goods sucked customers in, they would be diverted to a game of three-card

monte. In the game, the customers would be stripped of all money and, thus, there was

no danger of the goods actually being sold.

During Benton's brief existence, reputedly over 100

souls met their Maker in gunfights. One visitor referred to Benton as

"nearer a repetition of Sodom and Gomorrah than any other place in America."

On the other hand, General Grant during his 1868 visit to Wyoming visited the town. Additionally,

the town in August and September 1868, provided the jumping off location for

2,000 Saints in 5 companies heading to Utah. Of Benton, early western travel writer Samuel Bowles (1826-1878) wrote:

When we were on the line, this congregation of scum and wickedness was

within the Desert section, and was called Benton. One to two thousand men,

and a dozen or two women were encamped on the alkali plain in tents and

board shanties; not a tree, not a shrub, not a blade of grass was visible;

the dust ankle deep as we walked through it, and so fine and volatile that

the slightest breeze loaded the air with it, irritating every sense and

poisoning half of them; a village of a few variety stores and shops, and

many restaurants and grog-shops; by day disgusting, by night dangerous;

almost everybody dirty, many filthy, and with the marks of lowest vice;

averaging a murder a day; gambling and drinking, hurdy-gurdy dancing. Like

its predecessors, it fairly festered in corruption, disorder and death, and

would have rotted, even in this dry air, had it outlasted a brief sixty-day

life. But in a few weeks its tents were struck, its shanties razed, and

with their dwellers moved on fifty or a hundred miles farther to repeat

their life for another brief day. Where these people came from originally;

where they went to when the road was finished, and their occupation was

over, were both puzzles too intricate for me. Hell would appear to have

been raked to furnish them; and to it they must have naturally returned

after graduating here, fitted for its highest seats and most diabolical

service.

Bear River City, Wyoming Territory

Of a similar nature was Bear River City about 10 miles south of Evanston. Bear River City, 1867, pictured above,

is not to be confused with the city of the same name in

Utah, Bear River City, at its peak had a newspaper, The

Frontier Index, published by Legh R. Freeman (1842-1915). Legh Freeman,

a Confederate telegrapher,

was captured in 1864 and took advantage of amnesty afforded to those who would

become "galvanized Yankees," i. e. enlist in the Union Army for service in the

west. The end of the war found Freeman in Fort Kearney. Freeman, utilizing a box car as a printing office,

followed the tracks starting his newspaper in Fort Kearney, and

moving westward to Julesburg, Cheyenne, Fort Sanders, Green River City and Ogden. When word was recieved as to the

election of Grant, Freeman, remaining an unrepenitent Confederate sympathizer and not exactly the voice of moderation,

excited the attention of his readers, many of whom were Union veterans, by referred to Grant as

"the whiskey bloated, squaw ravishing adulterer, nigger worshipping mogul

rejoicing over his election to the presidency." Indeed, his views earned for his

paper the reputation of being that "filthy Rebel sheet."

Legh R. Freeman

Legh R. Freeman

Additionally, Freeman was not a milquetoast in expressing his opinions

as to fraud by the Railroad or his opinions as to others.

In the November 15, 1868 edition of The Index he expressed his

opinions as to Blacks, Indians and Chinese. If his opinions didn't get the attention of the gentle reader,

he persisted several days later with a vitriolic

attack on the L.D.S. and a call for the lynching of three accused murderers.

Following the necktie party, a group of vigilantes turned on him. Nineteen years later in the June 19, 1877 edition of the Ogden [Utah]

Freeman he described, with perhaps some exaggeration, the reason for his departure from Wyoming:

"The next morning at the break of day, when several thousand graders headed by the most villainous

desperadoes, beseiged the office, gutted and sacked it, and threatened to burn us in it, and would undoubtedly

have left nothing but a grease spot of our mortal remains had not a milk

white steed conveyed us to Fort Bridger, where we obtained troops, who arrested

the leaders and held the town under martial law until the large gangs of men

passed westward to the grading camps of Echo and Weber Canyon. Forty-odd

rioters are buried around the office. the only citizen killed in the melee

was Steve Stokes. The last of the cutthroats has died with his boots on and the ringleader had

his head chopped off with an ax."

Freeman, however, was irrepressible. Within a few months he resumed publication in

Montana, renaming the paper the Frontier Phoenix. He explained,

"the Institution shall rise, Phoenix-like, from her ashes, to still

advocate the cause of right and truth, to denounce tricksters and mobocracy,

uphold the good and faithful."

Union Pacfic under construction, Echo Canyon, 1869, photo by Wm. H. Jackson

Union Pacfic under construction, Echo Canyon, 1869, photo by Wm. H. Jackson

The graders from Echo Canyon were, however, a bit rough. When the Echo Canyon saloon was

torn down years later, seven human skeletons were found under the floor boards. A more

accurate version of the November 19, 1868, Bear River City Riot was described by George Crofutt in his

1872 edition of Crofutt's Trans-Continental Tourist's Guide:

The Bear River City Riot cost sixteen lives, including that of one citizen.

The mob first attacked and burned the jail, taking thence one of their kind who was

confined there. They next sacked the office and destroyed the material of the

Frontier Index. Elated with their success, the mob, numbering about 300 well-armed

desperados, marched up the main street and made an attack on a store, belonging to

one of the leading merchants. Here they were met with a volley from Henry rifles, in

the hands of brave and determined citizens, who had collected in the store. The

mob was thrown into confusion and fled down the street, pursued by the citizens, about

thirty in number. The first volley and the running fight left fifteen of the

desperados dead on the street. the number of wounded was never ascertained, but

several bodies were afterwards found in the gulches and among the rocks, where they had

crawled away and died. One citizen was slain in the attack on the jail.

By 1872, Crofutt reported that nothing of Bear River City was left except some chimneys and rusted oyster tins.

With Victorian rectitude and between the lines, Crofutt was relaying to his

readers the nature of the facilities at Bear River City. In the 19th Century West, oysters

were commonly believed to have had an affect on the libido. Roger L. Welsch in his Catfish at the

Pump: Humor and the Frontier, University of Nebraska Press, 1986, observed,

"Garbage dumps of 19th century 'hog ranches' are distinquished by the preponderace of

oyster tins."

Among those who assisted in putting down the riot was a former New York City

police officer, Thomas James Smith. Smith, as a result of his actions, earned the

appellation "Bear River Tom." Smith subsequently became the first town marshal of

Abilene, Kansas. There he, among other things, closed down the "Red Light District" after

a murder in one of the "dens of iniquity." Smith was killed on November 2, 1870,

while attempting to arrest Andrew McConnell. Smith was buried in a $2.00 grave. In 1904 the

City removed his remains to a more prestigious part of the cemetary and provided a grave marker. Smith's

year of birth is given by various sources as 1830, 1835, and 1840.

Thus, as the railroad crews and the assorted hangers-on moved westward, the population of the

Territory declined. In 1868, at the peak of railroad construction, the Territory had a population of about 16,000, but by

mid-1869 the population was only a little over 8,000.

Ames Monument, 2001, photo by Geoff Dobson

When the writer arrived at the above scene for the purpose of taking

some photos, an individual from the blue minivan was relieving himself on the

monument. Perhaps, but not likely, he was expressing his opinion from an historical perspective of the Ames

Brothers in whose honor the monument was erected. Indeed,

in an historical context one might not feel too kindly of Oliver Ames, Jr. (1807-1877) and

Oakes Ames (1804-1873). The two were at the very center of one of the greatest financial scandals in the

history of the American body politic, a scandal which swirled around the financing for the

Union Pacific and which implicated in allegations of

bribery the Vice President of the United States Schuyler Colfax, the Speaker of the

House of Representatives James G. Blain, the Republican candidate for vice president Henry Wilson, and

a future president of the United States James A. Garfield, as well as numerous

congressmen.

Bas-Relief by August Saint-Gaudens, Ames Monument, photo by Geoff Dobson

In the 1860's the attention of Oakes Ames, a congressman from Massachusetts, and

his brother was drawn to the Union Pacific and the generous subsidies it was receiving

from Congress. The two, having made a fortune in the management of their

father's shovel works which boasted of an average yearly production of over 1,400,000

shovels a year, acquired control over the Union Pacific. As a part of their scheme

to take advantage of the government subsidies, they also acquired control of a

Pennsylvania corporation which they renamed Credit Mobilier. The Union Pacific then

contracted with Credit Mobilier to construct 667 miles of the railroad. The actual

cost to Credit Mobilier was $44,000,000. The contract, using government subsidized funding, was for more than

$94,000,000. In order to preclude Congressional investigation, a large block of

Credit Mobilier stock held by Congressman Ames as trustee was ostensibly "sold" to

influential congressmen for one-third of its actual value. However, the "sale"

did not require actual money. The sales price was paid from the dividends resulting

from the profits on the railroad construction. Ultimately, the scandal was revealed by

the New York Sun. Although no one was indicted, Congressman Ames was censured by

Congress and died several months later, his reputation ruined. The Union Pacific was left heavily in debt.

Oakes Ames

The monument, itself, was designed by Henry Hobson Richardson, who was also the architect for

the Marshal Field's Store in Chicago. It has been contended that Richardson in his design

was inspired by the philosophy of Frederick Law Olmstead, designer of

New York's Central Park. Indeed, at the time the monument was under construction Olmstead wrote a

member of the Ames Family that it "was customary to commemorate important events by a form of monument * * * *

by bringing together at a place agreed

upon a great quantity of loose field stones and laying them up in the

conical pile known as a cairn."

The bas-reliefs of the Ames Brothers on either side

of the monument were sculpted by August Saint-Gaudens, famous as the designer of the

$20.00 gold piece.

Music this Page: Marching Through Georgia. As indicated above, many of the railroad workers were

Union veterans. One of their favorite songs was Marching Through Georgia.

Next page, Sherman and Dale Creek Bridge.

|