Citadel Rock, A. J. Russell, 1868

Citadel Rock is, perhaps, A.J. Russell's most famous photo with it being featured in Geoffrey C.

Ward's The West, an Illustrated History, as well as on PBS's The West website, although there divided into two

seperate pictures.

Note that the locomotive is on a temporary wooden bridge while the stone piers and abutments for the permanent bridge

are being constructed. In the race with the Central Pacific, many of the bridges such as the

Green River Bridge and the Dale Creek Bridge were temporarily constructed of wood only to be

replaced later with permanent structures of iron or stone. This had an adverse

impact on the Railroad's finances in that the road had to be almost entirely reconstructed.

John S. "Jack" Casement

John S. "Jack" Casement

Following his appointment in 1866 as chief engineer, overall engineering and

planning for the route of the railroad was placed under the supervision of

Grenville M. Dodge (1831-1916). Dodge, as was Lander, was a graduate of

Norwich University. Dodge, prior to the Civil War, had been an engineer under Peter Dey for

the Illinois Central and what later became the Rock Island. During the War he provided intelligence

for U. S. Grant in the Western Theatre and rose to the rank of major general. Following construction

of the Pacific Railroad, he was president of seven different railroad companies including the

Texas and Pacific, and 9 railroad

construction companies. He served as Grand Marshal for the funeral of former president

Grant.

In charge of logistics and construction were the actual contractors, the Casement Brothers,

Dan and Jack Casement. Dan was in charge of payrolls, at times dipping into his own pocket to meet payrolls, and accounting and Jack in charge of the

actual construction. Jack Casement served during the Civil War, first in

a volunteer Ohio unit and was at the Battle of Winchester. Later he served in Tennessee. At the

end of the War, he was breveted as a brigadier general and was, thus, referred to be

workers on the railroad as "General Jack." In the final push of the railroad, Casement's train grew in

length to 80 cars, including payroll and telegraph car, bunk cars, and a butcher car which supplied

fresh beef to workers from a herd driven along the right-of-way.

Attack on Handcar, Leslie's Illustrated News, 1870

A major difficulty in the construction of the railroad through Wyoming was constant attacks by the

Indians. Excerpts from the diary of Arthur N. Ferguson, a member of a Union Pacific survey party, are illustrative:

Tuesday, April 28, 68-I had an early breakfast in the morning and during

the entire day we had nothing to do. A few days ago four men were shot by

the Indians and were brought into this post-one of them died from the

effects of his wounds last night and during today, the soldiers have been

digging his grave. Another of the wounded men I hear is not expected to

live.

* * * *

Friday, May 1, 68-This is a fine morning and we have a pretty fair start.

During our days travel we have been through a pretty bad Indian country

and were liable at any and every moment to be attacked. I am thankful to

God for preserving us. We camp tonight with Fitzgerald's grading force and

Storm's Engr. Corps, and are in sight of where Clarke was killed by Indians

last year. After supper we had occasion to go to a spring but a short

distance from camp and for safety three of us went well armed. Beautiful

moonlight night.

May 2, 68-Got an early start this morning and have traveled all day

through a terrible country, the desolation of which is awful. We have

mounted men to our right but can't make out whether they are Indians or

not. We pass through the most dangerous part of our road today and at

noon we passed within a few miles of a camp of several hundred hostile

Indians. There are only five men of us in all and a little over 300 rounds

of ammunition, and the risk and exposure is so great that it is like

taking a man's life in his hand. We make camp tonight near some soldiers

and are comparatively safe. We have had a very anxious day of it-being on

the lookout from morning until night, not knowing but what we might be

attacked at every turn of the road. We have kept our arms loaded and

capped in our hands all day so as to be ready at an instant's warning.

I feel thankful for having been preserved today. Our mules got away this

evening but John, our driver, recaptured them before dark.

Between his duties, Ferguson "read law," ultimately becoming a lawyer in

Nebraska.

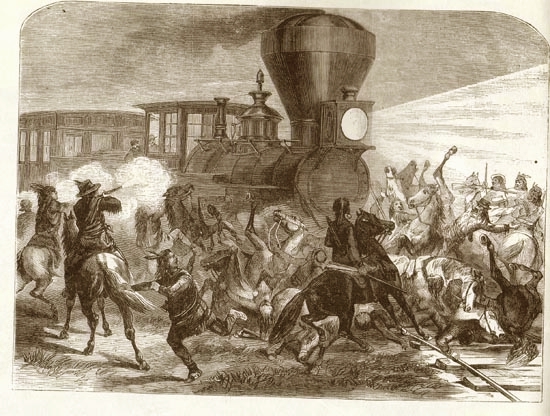

Indian Attack on Train, Leslie's Illustrated News, July 9, 1870

The above photo illustrates an attack upon a Union Pacific train east of Cheyenne on June 14, 1870. The train made

good its escape.

Gen. Dodge continually complained to Gen. Sherman about the Indians, ultimately writing

Sherman, "We've got to clean the Indian out, or give up. The government may take its choice."

To solve the problem, the Military established forts to protect the railroad and its

workers. Thus, there were established Ft. D. A. Russell near Cheyenne, Ft. Sanders south of

present day Laramie, Ft. Fred Steele where the Railroad crossed the North Platte, and Ft. Rawlins.

Ft. Bridger was activated and expanded. Of those forts, only D. A. Russell became permanent, now knows as

Warren Air Force Base. Thus, in once sense, Wyoming has an Air Force base that predates the

invention of the airplane.

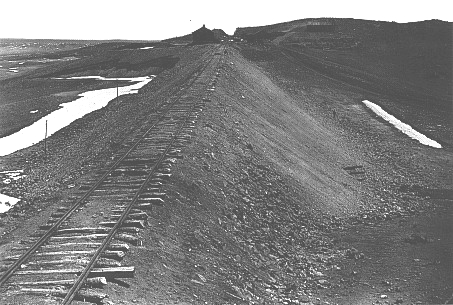

Granite Canyon fill, 1868, photo by A. J. Russell

The race to extend the railroad resulted in sloppy construction and engineering.

The Granite Canyon fill was the largest fill section on the railroad, but, as will be observed in the

photo, it was not well constructed. Note the ties extending beyond the edge of the

grade and, indeed, closest to the viewer, the rails are beyond the edge of

the fill. Isaac N. Morris, a Washington lawyer, was appointed by the government as a commissioner to determine

whether the railroad was being constructed in accordance with appropriate

engineering standards. In his 1869 report, Morris observed that Congress required that the

railroad should be a "first class" railroad and that the road bed should have been 14 feet in

width. He noted:

The Union Pacific road-bed is neither of these. Its width at the grade-line on embankments,

especially where it should be the widest, if any difference existed,

is only the width of the tie, or 8 feet, sometimes a little over and

sometimes a little under. In several places I saw the ends of the ties

projecting over the embankment.

Ultimately, almost the entire line had to be rebuilt. The report by Morris was not furnished

to Congress until 7 years later.

But one should not necessarily think ill of the hasty and poor construction. In an article, "The Building of

a Railway," Scribner's Magazine, June 1888, civil engineer Thomas

Curtis Clarke noted

"the almost uniform [American as opposed to British] practice of getting the road open for traffic in the

cheapest manner and in the least possible time, and then completing it and

enlarging its capacity out of its surplus earnings, and from the credit which these earnings give it."

Clarke continued:

The Pennsylvania Railroad between Philadelphia and Harrisburg is a notable

example of this. Within the past few years it has been rebuilt on a grand scale, and in many places re-located,

and miles of sharp curves and heavy gradients, originally put in to save

expenses, have been taken out. This system has been followed everywhere,

except on a few branch lines, and upon one monumental example of failure --

the West Shore Railroad, of New York. The projectors of that line attempted in

three years to build a double-track railroad up to the standard of the

Pennsylvania road, which had been forty years in reaching its present

excellence. Their money gave out, and they came to grief.

The distinction between the American practice of building on the

cheap and the British practice may be indicated by the relative speed of early railroads.

As noted later with regard to President Hayes visit to Wyoming in 1880, the presidential train

on the Union Pacific achieved speeds of 35 miles per hour. Forty years

before, Queen Victoria's royal carriage (complete with a crown on the

roof) on the Great Western proceeded at 50 miles per hour. The difference was the condition of the

track. It should be noted, however, that in 1876, four years before the presidential tour,

the Jarrett & Palmer Special achieved a speed of 72 miles per hour between Grand Island and North Platte,

Nebraska. The track, however, had a speed limit of 45 mph. The "Jarrett & Palmer Special,"

sometimes referred to as the "Transcontinental Express," whisked Broadway impresarios

Henry C. Jarrett and Harry Palmer and three Shakespearan actors from New

York to San Fanscisco in 83 hours and 39 minutes, a record not broken for another 50 years.

Jarrett & Booth leased the Booth Theatre in New York located on the south side of 23rd Street between

Fifth and Sixth Avenues. The theatre was owned by Oliver Ames who obained

it at foreclosure. Jarrett & Booth offices were located in Tammany Hall

in New York.

According to the detective Alan Pinkerton in his 1877 Strikers, Communists, Tramps and Detectives,

N. W. Carleton and Co.,

when the train paused in

Cheyenne, a nineteen year old hobo hopped the train and climbed to the

roof of one of the cars where he perched as the train made its long slow

ascent to Sherman. At Sherman, the engineer poured on the coal and with

the great speed of the train, the hobo had to hold on for dear life to a smoke-pipe serving

the car's stove. According to Pinkerton, parts of the hobo's

clothing was torn off and he was pelted by the cinders which "like the fiercest

hail, burned into his clothes, cut his arms, legs and face, and beat upon

the poor fellow's head remoreselessly." Pinkerton indicates that the hobo

was fnally taken off the train at Green River City. The story should be taken

with a grain of salt. At the time, trains normally paused for water every

fifty miles.

Later, Jarrett & Palmer moved to the UK were they successfully produced Uncle Tom's Cabin. Palmer died in the UK.

The West Shore, alluded to by Clarke, was constructed from New York to Buffalo along the

west shore of the Hudson and was intended to compete with Henry Vanderbilt's New

York Central. In retaliation, Vanderbilt cut rates and commenced construction of a

railroad in Pennsylvania to compete with the West Shore's parent The Pennsylvania

Railroad. It is more likely that it was the ruinous rate cuts by Vanderbilt that

bankrupted the West Shore, which was then acquired by the New York Central.

Clarke's observations were presaged over thirty years before in F. W. Lander's report to Congress.

In that report, Lander contended that the only way the road could be constructed was to do it

on the cheap and correct the mistakes later.

Not having anything to do with Wyoming, but an interesting side note, was the involvement of Morris'

firm with one of the great mysteries of the Nineteenth Century, the disappearance of the Great Seal of the Confederate

States of America. In 1863, Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, pursuant to a Resolution of the

southern Congress, commissioned Her

Britannic Majesty's engravers to create out of solid silver the Great Seal. The

Seal, inspired by the design of the Seal of William and Mary, bore an image of an

equestrian George Washington and the Confederate States motto, Deo Vindice ("God Vindicates").

From the time of the Middle Ages, the possession of a seal was proof of authority. Thus,

even today, corporations, governmental bodies, and public officials authenticate documenents by

impressing thereon a seal. Even private contracts and deeds will frequently bear after signatures the letters

"L. S.," Locus Sigilli ("Place of the Seal").

Lieutenant Robert T. Chapman, Confederate States Navy

At great personal risk and under direct orders that under no circumstances should

he permit the Great Seal to be captured, a Confederate naval officer, Lieutenant Robert T. Chapman,

via way of Halifax and Bermuda, escorted the Great Seal through the Federal blockade to Richmond.

In April 1865, President Davis and the Confederate government were required, as a result of the

fall of Petersburg, to evacuate the capital. Missing upon Federal occupation were Confederate archives and the Great Seal.

Following the war, copies of the Great Seal were produced by a Washington, D.C. jeweler and sold to raise funds for

Confederate widows and orphans. The Great Seal, itself, remained missing. Rumors as to

its fate were rife. One rumor was that President Davis had entrusted the Seal to a

faithful former slave, James H. Jones, who buried it near Washington, Georgia. In recognition of his

services in preventing the Seal from falling into Federal hands, Jones was allegedly given

a pension.

In 1868, William J. Bromwell, an attorney with the Morris law firm, had a former Confederate diplomat, Col. John T. Pickett,

approach Secretary of State William Seward about sale to the government of certain Confederate

archives then located in Canada. By 1871, Congress appropriated $75,000 for the purchase of the

archives. Secretary Seward had a young naval lieutenant, Thomas O. Selfridge, accompany Pickett to

Canada to authenticate the documents. With the purchase of the Archives, Bromwell's involvement with the sale

of the Archives was revealed. During the

war, Bromwell was Chief Clerk for the Confederate State Department and was responsible for preparation of a digest of

Confederate Acts of Congress. After the fall of Richmond on instructions from Secretary

Benjamin, Bromwell secreted the archives in a barn in North Carolina. Later he had Col. Pickett transport the

records to Canada for safe keeping. Upon shipment of the archives to Washington in 1872, it was discovered that the

Great Seal was not included, nor was it included within the inventory of the papers. The sale of the

Archives caused a landslide of outrage from former Confederates. Bromwell fled into

exile in Britain where he died alone and in poverty in Chelsea

The mystery of the Great Seal remained and, like the search for the Holy Grail, excited public

interest. Indeed, Mark Twain used the theme of the missing Great Seal of England, as the

central plot device in The Prince and the Pauper. There, it will be

recalled, Prince Edward and a pauper changed places. While they had changed places, Henry VIII died, but the

Great Seal could not be found. As the imposter was about to be crowned as King, the real

Prince Edward appeared in the pauper's rags. Although disbelieved at first,

Edward was able to prove that he was the real king because he

knew the location and significance of the Great Seal, while the imposter never recognized its

significance.

In 1912, 47 years after the end of the Civil War, the Library of Congress conducted a re-review of

the Confederate Archives. This led to a suspicion that the Great Seal had originally been with the

Archives in Canada and that it had been taken by Selfridge. Gallard Hunt,

of the Library of Congress, confronted Selfridge, who by then was a

retired rear admiral. Threatened with disgrace, Selfridge agreed to sell the Great Seal to

an appropriate museum in Richmond for $3,000. With the recovery of the Great Seal, Bromwell's

widow revealed that during the evacuation she removed the Seal from Richmond in her bustle and that she had entrusted it

to Pickett for safe keeping. Pickett, in turn, carried it to Canada and placed it with

the Archives. Selfridge contended that Pickett had given it to him in gratitude.

Next page, "Hell on Wheels", the Credit Mobilier Scandal.

|