|

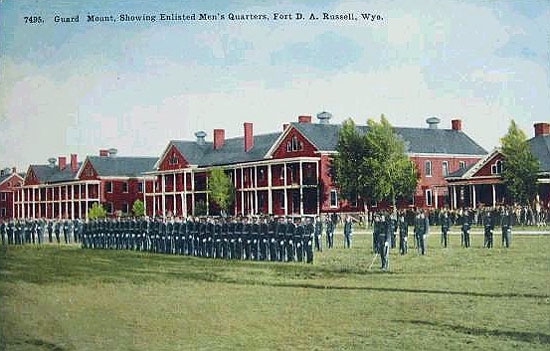

Guard Mount before enlisted men's barracks, Ft. Russell, 1909.

For discussion of "Guard Mount" see Fort Laramie.

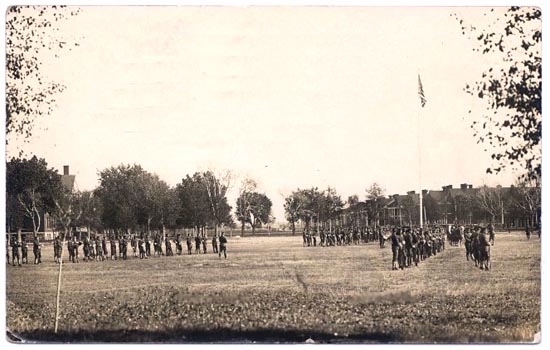

Guard Mount, 1912.

Near the base flagpole, for many years there was a memorial to Soldiers and Sailors who died

in the Philippine Insurrection of 1899-1902. The memorial consisted of two bells,

the Bells of Balangiga. In recent years the bells were stored away in a warehouse. Strong feelings existed in the Philippine Republic regarding the

memorial. Many in the Philippines wanted the bells to be returned as a memorial to the

war of Philippine Independence against the United States, others as a memorial to Philippine-American

Friendship.

Guard Mount, 1920'S.

Overvew of Spanish-American War

(Wyoming involvement on following ages)

In 1896, the crumbling Spanish Empire faced a rebellion in its

distant colony of the Philippines. Other insurrections broke out in Cuba, supported by

Cuban exiles in Key West, Tampa, and St. Augustine, Fla. By 1898, it had become apparent to Assistant Secretary of

the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, that there would be war between the United States and Spain and Admiral

Dewey was dispatched to the Pacific. When war was finally declared, the fleet was already in the

Pacific ready to attack Manila. Troops from the Wyoming National Guard were assigned to the

war in the Philippines and, indeed, were the first to enter Manila. It has been contended that

Admiral Dewey received the cooperation of Philippine revolutionaries under General Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy

based on a promise that

following the war, the independence of the Philippine Republic would be recognized.

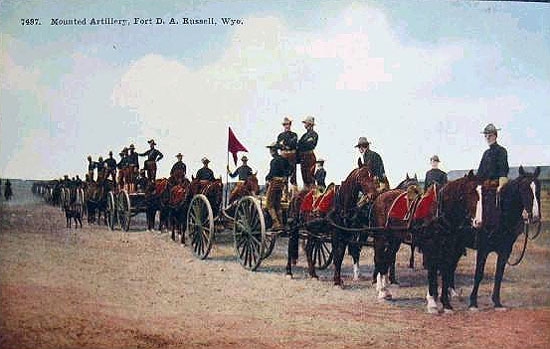

Mounted Artillery, Ft. D. A. Russell, 1909

At the conclusion of the Spanish-American

War, the United States received possession of Cuba which was given its independence, first as a protectorate, and

later as an independent republic, with, however, the United States retaining possession of

Guantanamo. The United States also received Puerto Rico and Guam, the latter under the

jurisdiction of the Navy as a coaling station. The Philippines were purchased from

Spain and the question arose as to their future. The United States had a concern that if the

islands were given their independence, they would be picked off by Germany which beginning in the 1880's had become increasingly

expansive in the Pacific annexing the Northern Solomon Islands, a portion of New Guinea, the Carolines, Palau, a

portion of the Marshall Islands, the Marianas and Nauru.

General public opinion, urged on by concerns that the nascent government of General

Aguinaldo would not be able to maintain civil order, and that it was a moral

duty and obligation

of the United States to bring civilization to the Islands, supported the proposition that the Philippines should be annexed.

This attitude was exemplified by a dream of President McKinley and the writings

of Rudyard Kipling who published his The White Man's Burden in

McClure's Magazine in February 1899. In it he urged the United States, not withstanding the difficulties,

inimicality from natives, blood and treasure, to annex the Islands:

Take up the White Man's burden--

In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror

And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple,

An hundred times made plain,

To seek another's profit

And work another's gain.

Take up the White Man's burden--

The savage wars of peace--

Fill full the mouth of Famine,

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

(The end for others sought)

Watch sloth and heathen folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Take up the White Man's burden--

No iron rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper--

The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter,

The roads ye shall not tread,

Go, make them with your living

And mark them with your dead.

When it became apparent that the United States was to retain the Philippine Islands, the

war fought by Filipinos against Spain continued against the United States. American troops were

thus required to be stationed in the Islands. These included the 11th Infantry a portion of which had

as its home base Fort D. A. Russell, and units of the 9th Infantry. Many of the commanders such as

Major General Wesley Merritt and General Arthur MacArthur had previously seen

duty in the Indian Wars in Wyoming.

Officers' quarters, Ft. D. A. Russell, undated

Company C of the 9th Infantry served as an honor guard at the inauguration of Philippine Governor Wm. H. Taft in 1901.

On August 11, 1901, Company C was assigned to the small town of Balangiga on Samar which was then

being beseiged by guerillas from the surrounding countryside. Filipinos argue that it was the town that

was being beseiged and starved by the Americans. The guerillas were led by

General Vincente Lucban. It has been contended that when soldiers ventured out into the

countryside, priests from the church at Balangiga would alert the guerillas by ringing

the bells. This is disputed by the Filipino sources. Elsewhere in the Islands, captured Americans were tortured and their noses and ears cut off. Capt.

Paul Melshen in Proceedings, U. S. Naval Institute Nov. 1979, noted a later occasion when a

pro-American Filipino was captured, his head wrapped in an American flag, doused with

kerosene, and set alight.

Bells of Balangiga, Fort D. A. Russell, approx. 1910

A second memorial to those who fought in the Spanish-American War stands on the southeast corner of the

Capitol Ground in Cheyenne, a statue of a Wyoming Volunteer "Taking the Oath." It is depicted on the pages devoted to the

State Capitol Building.

On the morning of September 28, 1901, as members of Company C were sitting down for

breakfast, the church bells began to ring and out of the church came guerillas armed with bolo knives

(sharpened cutlasses) and attacked the Americans. Additionally, other guerillas broke through a

convent and attacked the American barracks and the town hall. A Filipino study group consisting of

Bob Couttie, author of The Balangiga Attack; Professor Rolando Borrinaga, a Filipino writer; and

an American, Jean Wall-Fe; argue that the Americans were attacked by men under the

command of the local chief of police Valeriano Abanador. It was argued that only one bell rang and that was

after the attack commenced. Of the 74 men of Company C, 48 were killed or missing. Those

killed were mutilated. Twenty-two were wounded. Only four were unharmed. The survivors made

their escape by boat.

The guerillas had entered the church the night before disguised as women attending

a funeral for children. According to Joseph L. Schott's 1964, The Ordeal of Samar, an American

sergeant of the guard was told that the

children died of cholera. He was shown the dead body of a child in a casket and

told, "El calenturon! El colera! No cholera had, however, been reported in the area.

The weapons were concealed in the caskets. Filipinos contend that there were no caskets and that the

American saw a statue used in religious ceremonies the day before. The next day, relief troops retook the town. Later troops took

the three bells from the Church. One bell was later presented to the

survivors of Company C, see next photo. The 9th Infantry until December 2018 continued to hold the bell.

The other two bells made their way to the

11th Infantry on Leyte, and from there back to Fort D. A. Russell. In her 1914 autobiography,

Recollections of Full Years Mrs. Wm. H. (Helen) Taft recalled that subsequently

General Lucban boasted of "our glorious victory of Balangiga."

Survivors of Company C with bell, 1901

Retribution by special forces under Brig. Gen. Jacob H. Smith (a veteran of

Wounded Knee) and Major (Brevet Lt. Col.) Littleton Waller, USMC, was harsh. Smith

ordered that prisoners not be taken. Waller disobeyed the order and instead invoked President

Lincoln's General Order 100 from the Civil War, which permitted the summary killing of

persons in civilian clothing engaged in acts of war. Persons who surrendered were in fact

treated as prisoners. Both Gen. Smith and Major Waller were court martialed for their excesses.

Waller was found not guilty, although the verdict was strongly criticized by Gen.

Arthur MacArthur. Smith was removed from the service.

As noted, the bells remained a highly emotional source of controversy. The Philippines since at least 1947 requested the return of at least one

bell so that it could be used to commemorate the Philippines' War of Independence. The Philippine

Congress, in celebration of the massacre of the American troops, has declared September 28, "Balangiga Encounter Day." President Clinton, according

to a Manila newspaper agreed with this request, but return would require an act of

Congress. The Maryland Legislature has passed a resolution supporting the return and

the Congressional delegate from Guam has introduced a resolution calling for the return of one

bell. The Philippine Roman Catholic Church has taken the position that the

bells belong to the Church. Senators Craig Thomas (R. Wyo.) and Michael Enzi (R. Wyo.)

introduced legislation to require that

there be Congressional approval before any memorials were to be dismantled. Veteran groups in Wyoming opposed any

return of the bells. In December 2018 following efforts by VFW posts in the Philippines and resolutions by the American Legion, the bell

held by the 9th Infantry was flown from the Korea where it had been held. The two bells at

F. E. Warren Air Force base were flown to Japan. There they joined the 9th Infantry Bell.

From there the three were taken to the Philippines and

turned over to the Philippine government by the American ambassador.

Music this page, "Lupang Hinirang," the Philippine National Anthem as played by the United States Navy

Band. Lyrics set forth in the following Act of the Philippine Congress: WRITER'S NOTE:

Anyone subject to Phillipine jurisdiction attempting to sing or play the Phillipine National Anthem should be aware of the following:

REPUBLIC ACT NO. 8491

AN ACT PRESCRIBING THE CODE OF THE NATIONAL FLAG, ANTHEM, MOTTO, COAT-OF-ARMS AND OTHER HERALDIC ITEMS AND DEVICES OF THE PHILIPPINES.

* * * *

CHAPTER II

THE NATIONAL ANTHEM

SECTION 35. The National Anthem is entitled Lupang Hinirang.

SECTION 36. The National Anthem shall always be sung in the national language within or without the country. The following shall be the lyrics of the National Anthem.

Bayang magiliw,

Perlas ng silanganan,

Alab ng puso

Sa dibdib mo’y buhay.

Lupang hinirang,

Duyan ka ng magiting,

Sa manlulupig

Di ka pasisiil.

Sa dagat at bundok,

Sa simoy at sa langit mong bughaw,

May dilag ang tula

At awit sa paglayang minamahal.

Ang kislap ng watawat mo’y

Tagumpay na nagniningning;

Ang bituin at araw niya,

Kailan pa ma’y di magdidilim.

Lupa ng araw, ng luwalhati’t pagsinta,

Buhay ay langit sa piling mo;

Aming ligaya na ‘pag may mang-aapi,

Ang mamatay nang dahil sa ‘yo.

SECTION 37. The rendition of the National Anthem, whether played or sung, shall be in accordance with the musical arrangement and composition of Julian Felipe.

SECTION 38. When the National Anthem is played at a public gathering, whether by a band or by singing or both, or reproduced by any means, the attending public shall sing the anthem. The singing must be done with fervor.

As a sign of respect, all persons shall stand at attention and face the Philippine flag, if there is one displayed, and if there is none, they shall face the band or the conductor. At the first note, all persons shall execute a salute by placing their right palms over their left chests. Those in military, scouting, citizen’s military training and security guard uniforms shall give the salute prescribed by their regulations.

The salute shall be completed upon the last note of the anthem.

The anthem shall not be played and sung for mere recreation, amusement or

entertainment purposes except on the following occasions:

a. International competitions where the Philippines is the host or has a

representative;

b. Local competitions;

c. During “signing off” and “signing on” of radio broadcasting and

television stations;

d. Before the initial and last screening of films or before the opening of

theater performances; and

e. Other occasions as may be allowed by the Institute.

Next page: Torry's Rough Riders

|