|

Medical Department, 1888, in front of Post Hospital, Fort Laramie.

The post hospital was the first building at Fort Laramie constructed of lime grout, a locally

produced concrete. The building, constructed in 1873, housed a 12-bed ward, dispensary, dining room,

and post surgeon's office. Archeological investigation has revealed that the

hospital was constructed on the site of an earlier cemetery dating to when the fort was

owned by Sublette and Campbell and the American Fur Company.

Ruins of Post Hospital, Fort Laramie, approx. 1942. All rights reserved G. B. Dobson.

Ruins of Post Hospital, Fort Laramie. All rights reserved G. B. Dobson.

The fort was normally served by a post surgeon and assistant post surgeon who were officers. On occasion, however, there would

be employed contract physicians who were civilians.

Officers' Line, 1889.

On the extreme right in the photo is the edge of the Post Trader's store, see next photo, followed by the

Burt House discussed on the next page. The post trader or sutler on a military post

was a civilian who had a license to operate a general store on the post.

Although prices were regulated by the government, it remained a highly

profitable enterprize. The store at

Fort Laramie was constructed in 1849 and received several additions over the years,

the most recent being an 1883 addition housing the Officers' Club and the enlisted men's

bar. Today in the bar nothing is served stronger than sarsaparilla. But the

bartender is still friendly.

Sutler's store, Fort Laramie, 1877.

The Sutler's store from about 1866 was described as:

"[A} scene of surprising confusion. Indians dressed and undressed, squaws dressed to the

same degree of completeness as their noble lords (?), papooses absolutely nude,

slightly not nude, or wrapped in calico, buckskin, or furs,

mingled with soldiers of the garrison, teamsters, emigrants, speculators,

half-breeds, and interpreters. Here cups of rice, sugar, coffee, or flour were being

emptied into the looped-up skirts or blankets of the squaws, and there some tall

warrior was grimacing delightfully as he grasped and sucked his long stick of peppermint

candy. Bright shawls, red squaw-cloth, brilliant calicoes, and flashing ribbons passed

over the same counter with knives and tobacco, brass nails and glass beads, and that

endless catalogue of articles which belong to the legitimate border traffic. The room

was redolent of cheese and 'heap smoke,' while debris of munched crackers

lying loose under foot furnished both nutriment and employment for little Indians too

big to ride on mamma's back, and too little to reach the good things on the

counter or shelves. The 'Wash-ta-la' (very good) mingled with 'Wau-nee-chee'

(a very insignificant no good, whether predicated of person or thing); and the

whole scene was a lovely episode, illustrating the habits of the noble red man

in the mart of trade. Of course all these Indians were thinking sharply, and many

gave words to thought, so that an unsophisticated stranger might well doubt whether

Bedlam or Babel was the better prototype of the tongues in use. The Cheyenne supplemented

his words with active and expressive gestures, while the Sioux amply used his tongue as well

as arms and fingers in their forcible sign-language."James Regan

"Military Landmarks," United Service, Vol. 3, 1880 p. 148 et seq.

Following the Civil War, the title of sutler was changed to "Post Trader." The

longest serving sutler was Seth Ward (1820-1903), who held the license from 1857 to 1871 not

withstanding that he was a Confederate sympathizer. Indeed, during the Civil War, he vowed

that he would not shave until the South had gained its freedom. At the

time of his death in 1903 he still had a full white beard.

Ward started trading with the Indians at an early age, and by 1836 had formed a partnership with

William Guerrier and the two operated a trading post above Ft. John. It was short lived, however, and

Guerrier worked as an interpreter at Bent's Fort. Geary, Oklahoma is named after him. The two

resumed their partnership and operated a trading post for a short period of

time in 1851, 20 miles east of Ft. Laramie. The goods were brought by wagon from

Westport (present day Kansas City). The following year, 1852, the Ward and Guerrier trading post was moved

to Sand Point (Register Cliff).

Seventh Infantry Guard Mount, approx. 1889.

The building in the background is the post administration building constructed of lime grout at a cost of

$3,800.00 under the supervision of Lt. John T. Van Orsdale. "Guard Mount" was a formal ceremony usually conducted in mid-morning

marking the change of the guard. Elizabeth Custer in her Boots and Saddles recalled that in pleasant weather with

the adjutant and officer of the day in full uniform, each soldier perfect in dress, with the

band playing, it was an interesting ceremony. In winter, however, with everyone in buffalo overcoats, shoes, fur caps and gloves,

"it looked like a parade of animals at the Zoo." Guard Mount would commence with the assembly of trumpeters, followed by the assembly of guard detail and then

the adjutant's call and the guard mount ceremony each marked by bugle calls. But then, every moment of military life was seemingly guided

by bugle calls. Elizabeth Custer in her Following the Guidon recalled of the bugle calls:

It was the hourly monitor of the cavalry corps. It told us when to eat, to

sleep, to march, and to go to church. It clear tones reminded us,

should there be physical ailments, that we must go to the doctor, and if the

lazy soldier was disposed to lounge about the company's barracks, or his indolent officer to

loll his life away in a hammock on the gallery of his quarters, the bugle's sharp call

summoned him to "drill" or "dress parade." It was the enemy of ease, and cut short

many a blissful hour. The very night was invaded by its clarion notes if there chances to

be fire, or should Indians steal a march on us, or deserters be discovered

decamping. We needed timepieces only when absent from garrison or camp. The never tardy sound calling to

duty was better than any clock and brought us up standing; and instead of the

usual remark, "Why here it's four o'clock already!" We found ourselves saying:

"Can it be possbile? There's 'stables,' and where has the day gone?"

The horses knew the calls, and returned from grazing on their own

accord at "Recall" before any trooper has started; and one of them would

resume his place in the ranks and obey the bugle's directions as

nonchalantly as if the moment before he had lifted a recruit over his head

and deposited him on the ground."

The irreverent soldiers always added words to the various bugle calls. We all are familiar,

of course, with the "You gotta get up, you gotta get up, you gotta get up in the morning," but

words were added to other calls. Mess Call produced:

Soupy, soupy, soupy,

Without a single bean;

Porky, porky, porky,

Without a streak of lean;

Coffee, coffee, coffee,

Without any cream.

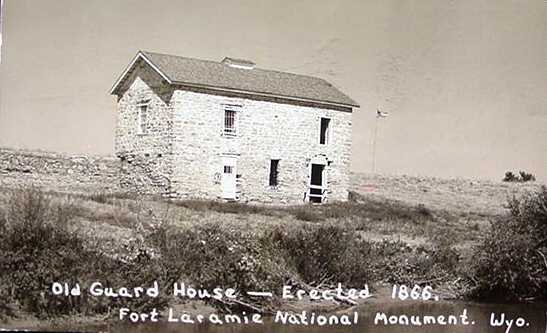

Old Guard House, photo by Littler

The Old Guard House was replaced in 1876 at the insistence of the Post

Surgeon by the New Guard House depicted on the next page.

Music this page:

Boots & Saddles March

Courtesy Horse Creek Cowboy

Electric Marching Band

Next Page: Ft. Laramie Continued.

|