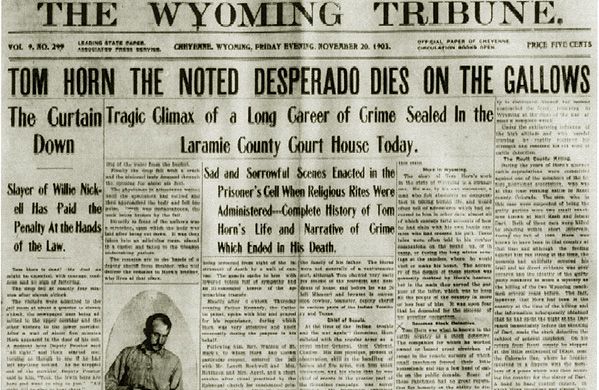

Headlines, Wyoming Tribune, November 20, 1903

On November 20, 1903, Horn was led to the gallows by Deputy Proctor and

T. Joe Cahill who at the time was a clerk. Cahill later served as

Chief of Police in Cheyenne 1934-1940 and was active in rodeo circles

including the Madison Square Garden Rodeo from 1928-33. Cahill apparently

exhibited some nervousness. Horn commented, "What's the matter, Joe? Ain't

losing your nerve, are you?"

Horn's legs and arms were strapped with a brand new set of five leather straps made by Meanea's Saddle Shop for the occasion.

The separate straps bound Horn's arms, wrists, and hands to his sides and beside his legs and knees. Another bound his ankles so that

the prisoner was completely immobile. The purpose of the straps was to preclude any writhing of the body in the

event that the drop failed to break

Horn's neck. The only thing that the spectators might see would be a slight vertical muscular twitching. Deputy Proctor placed the noose made from Horn's own rope over Horn's head. Horn

obliged by ducking his head and thrusting it through the noose. Sheriff Smalley and

Joe Cahill then picked Horn up and placed him on the trap.

For the execution, a new type of gallows was introduced using

an automatic trap activated by the weight of the convict, eliminating the

need for an executioner. The gallows were invented in 1892 by Cheyenne architect James P. Julian but had not been

used before. The gallows used a system in which the trap was supported by a two-piece

post resting on a spring. The weight of the convict on the trap, pushed down on the

post depressing the spring. This, in turn, opened a water valve. The water then filled a

can balanced on a cross beam. When sufficient water filled the can, its weight would cause

it to slip off, allowing the cross beam to knock the supporting post out of the way, thus, opening

the trap. This type of gallows remained in use until replaced

by the gas chamber. As Horn stood on the trap, the only sound was the sound of the water filling the can.

Colorado on occasion also used a water-activated gallows which, however,

operated on a different principle. Rather than the convict dropping through a trap, the Colorado

gallows used a 50-gallon tank which drained. A float in the tank was connected to

a lever. The lever when the tank drained would release a catch on a pivoting beam connected to a counter-weight. The beam to which the noose

was attached then jerked the convict upwards, hopefully breaking the convict's neck.

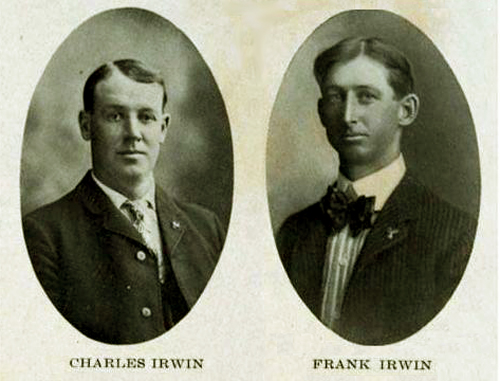

Irwin Brothers

Thus, as the Right Reverend Dr. Rafter of St. Marks Episcopal Church offered

prayers and two friends, Charles B. Irwin and Frank Irwin, sang the hymn

"Life is Like a Mountain Railroad," Horn was hanged.

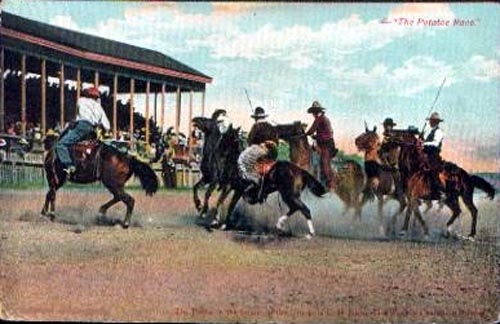

C. B. Irwin (in woolies) in Potato Race, Frontier Day, 1904. See text below. For discussion of

potato races, see Lusk.

Horn had been an entrant in the 1901 Frontier Day Steer

Roping Contest. Charlie Irwin, Frank Stone, and Duncan Clark also entered the

same contest. Clark came in first, taking the $65.00 first prize. Irwin took the

second place prize of $35.00, a fifth of a second behind Clark. Frank Irwin entered the

Cow Pony Race riding a horse named "Uncle Bob." All, at the time, were employed by Coble. The following year,

Charlie Irwin, Duncan Clark and his brother Hugh helped with the stock at Denver's Mountain and Plains Festival. Coble

provided some of the stock including the two best broncs Deadeasy and Steamboat. Frank Stone

was

one of the top five riders. At the completion of the

execution, Charlie Irwin noted, "He sure died game."

Tom Horn being placed in hearse at Gleason's Mortuary. Charles Horn at right.

Horn's body was claimed by his brother Charles, an expressman from Boulder, Colorado.

In a later letter to Coble, Charles Horn noted

that he had failed to write his brother prior to the execution.

Horn was buried in Boulder, Colo. The funeral expenses were paid for by Coble. A

guard was posted at the grave.

As a result of an altercation between Coble and Nickell at the railway station over Nickell's sheep,

the suspicion has always been that Coble paid Horn to do in Nickell. This has never been

proven and it may well be speculated that Horn was merely performing an

unsolicited favor of ridding the neighborhood of a sheepman.

In 1903, Coble sold his interest in the Iron Mountain Ranch to his partner Henry Bosler.

Later each accused the other of fraud. After Bosler refused to

pay Coble what he was due, Coble successfully sued Bosler in a bitter action which

went all the way to the Wyoming Supreme Court. Coble nevertheless lost his fortune and went to work as a foreman for

a ranch in Nevada. In 1914, he was let go. On December 4, 1914, shortly after midnight, Coble entered

the coffee shop of the Commercial Hotel in Elko through the 4th Street entrance, proceeded to the lobby and asked

the night clerk for some stationery. He wrote out a note to his wife, and committed suicide in an unoccupied

ladies' restroom using a .32 Smith and Wesson.

Commercial Hotel, Elko, Nev., approx. 1949

Duncan Clark was killed in a hunting accident in April 1906 near Horse Creek

where he was then residing. His death has been used as the basis for various

conspiracy theories. Such theories include: (a) Willie Nickell was killed by Victor Miller using a gun

similar to Horn's Winchester so as to blame Horn; (b) Willie was killed by Jose

"Joe Good" Bueno, an outlaw from Brown's Hole, Colorado; and (c) the Wyoming Stock Growers Association conspired to "blow" the

defense and see Horn hanged rather than have him reveal their being involved in

the killings. A review of Justice Potter's opinion, Horn v. State, 12 Wyo. 80, 73 Pac. 705 (1903),

reflects that every argument in

Horn's favor was raised and carefully considered by the Wyoming Supreme Court. The

Horn case is still cited as precedent in Wyoming courts. It is

extremely doubtful that a lawyer of John Lacey's reputation would join a conspiracy to

lose the case. Extraordinary efforts were made to save Horn including, as

above indicated, appeals to the governor for

clemency.

Some, such as the unknown writer, excused Horn:

It is possible, although highly doubtful, that he killed none at all

but merely let his reputation work for him by privately claiming every

unsolved murder in the state.

It is also possible, but equally doubtful, that he actually shot down

the hundreds of men with which his legend credits him.

For that legend was growing explosively, Rumor was insisting he received

a price of $600 a man.

The best evidence is that he received a monthly wage of about $125, very good money in an era when top hands worked for $ 30 and board.

Rumor had it he slipped two small rocks under each victim's head as a sort of trademark

A detailed search of old coroner's reports fails to substantiate this in the slightest.

One thing was certain -- his method was effective, so effective that after

a time even the warning notices were often unnecessary.

The mere fact that the tall figure with the rifle and field glasses had been seen riding that way was enough to frighten three rustling homesteaders out of the Upper Laramie country in a single week

"My reputation's my stock in trade", Tom mentioned more than once.

He evidently couldn't foresee that it might be his downfall in the end.

He had made himself the personification of the Devil to the homesteaders.

But to the cattlemen who had been facing bankruptcy from rustling losses

and to the cowboys who had been faced with lay-offs a few years earlier,

he was becoming a vastly different type of legendary figure.

Such ranchers as Coble and Clay and the Bosler brothers carried him

on their books as a cowhand even while he was receiving a much larger

salary from parties unknown.

He made their spreads his headquarters, and he helped out in their roundups

In the cow camps, Tom Horn was regarded as a hero, as the same kind of

champion he was when he entered and invariably won the local rodeos.

The hands and their bosses saw him as a lone knight of the range,

waging a dedicated crusade against a lawless new society that was

threatening a beloved way of life.

The wailing , guitar-strumming minstrels of the cattle kingdom

made up songs about him.

By 1898, rustling losses had been driven down to the lowest level

ever seen in Wyoming.

Horn Grave, Columbia Cemetery, Boulder, Colo., photo by Geoff Dobson

In the final analysis, it must be said the jury was there, they heard the witnesses, and,

upon consideration of all the evidence, they found they had no other choice but to

find Horn guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Thus, the mystery of Tom Horn, the one he took to

his grave, is not if he killed Willie Nickell. Unanswered questions remain after 100 years: Who paid Horn the

$2,100; who paid Horn to kill Isom Dart, Matt Rash, William Lewis, and Fred Powell; and who actually

wrote Tom Horn's autobiography. Was it Horn, as claimed by Coble's widow, or Hattie

Horner Louthan, a sometimes newspaper correspondent and member of the staff of the

Denver Republican? And what of Glendolene Myrtle Kimmell? Miss Kimmell, who stuck by Horn to the end and who blamed

Victor Miller for the killing, never married. She allegedly wrote a manuscript,

The True Life of Tom Horn, portraying Horn as a knight errant caught between two

conflicting worlds. It was never published. What whould it have

revealed? Unfortunately we may never know for Miss Kimmell died at age 70 in Los Angeles, California, on

September 12, 1949. And who is the author of the fragment copied above found

at a Canadian university?

Directions to grave: From Broadway take College Avenue west to

cemetary. Next to cemetery on north side, street widens to permit parking. Grave is at 2:00 o'clock

position from first parking space, about 10 graves in.

|

SHEDRICK

In an effort to explain Horn, some have focused on Horn's relationship to his father, mother, and

dog Shedrick. In Chapter 1 of his autobiography, Horn discusses his dog and the lack of recognition

given by his mother to Horn's ability at tracking varmints. Whenever a varmint would

invade the chicken coop, young Horn would be sent out to capture the culprit, but the dog would receive the

credit:

For a kid, I must have been a very sucessful hunter, for when our

neighbors would complain of losing a chicken (and that was a serious loss to them),

mother would tell them that whenever any varmint bothered her hen-roost, she just sent out Tom and

"Shed," and when they came back they always brought the pelt of the varmint with them.

To this day, I believe mother thought the dog was of more importance against vamints than I was. But "Shedrick" and I

both understood that I was the better, for I could climb any tree in Missouri, and dig frozen

ground with a pick, and follow cold tracks in the mud or snow, and knew more than the dog in a good

many ways.

Horn continues by noting that his father would beat the dog and the dog would then not leave Tom for days thereafter.

In the book, Horn describes the death of Shedrick as the "climax" of his home life. Horn

got into an altercation with two emigrant boys following behind their parents

wagon. The fight started when Horn made a crack about the manliness of the larger

boy's choice of weapons, a shotgun. When Horn was getting the better of

the larger of the two, it became two on one. At that point Shedrick came to young Horn's rescue. At the

conclusion of the fight the larger of the two emigrants shot Shedrick. Horn took the dog home

and buried him.

Thus, it may be that Horn did not envision himself as a palidin, but, instead, was subconsciously

still out with Shedrick tracking varmints who had raided his neighbors' and friends' chicken coops, and by

so doing, seeking the approbation of society.

|

Music on this Page: Life is Like a Mountain Railroad

by Eliza R. Snow and M.E. Abby

Life is Like a Mountain Railroad

Verse

Life is like a mountain railroad

With an engineer so brave

We must make this run successful

From the cradle to the grave

Watch the curves, the fills the tunnels

Never falter, never fail

Keep your hand upon the throttle

And your eye upon the rail

Refrain

Oh, blessed Savior, thou wilt guide us

Til we reach that blissful shore

Where the angels wait to join us

In God's grace forever more

Verse

As you roll across the trestle

Spanning Jordan's swelling tide

You behold the union depot

Into which your train will glide

There you'll meet the superintendent

God the Father, God the Son

With a hearty, joyous greeting

Weary pilgrim, welcome home

Refrain

Next Page: The Wild Bunch

|