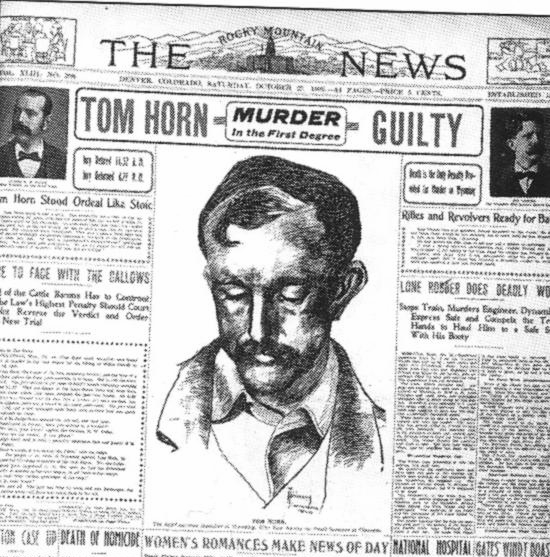

Rocky Mountain News Headline, Saturday, Oct. 25, 1902.

On October 23, 1902, after a two week trial, the jury of 11 whites and one black, Charles H. Tolson,

found Horn guilty on the sixth ballot. The jury was one which at least on first glance might be considered as being favorable to Horn:

|

H. W. Yoder, Ranchman, Goshen Hole

O.V. Seeburn, Ranchman, Goshen Hole

Charles Stamm, Ranchman, Wheatland Flats

T. R. Babbit, Ranchman, LaGrange

H. W. Thomas, Ranchman, LaGrange

G. W. Whiteman, Ranchman, Uva

Amos Sarbaugh, Foreman, Swan Land and Cattle Company

Homer Payne, Cowboy, Swan Land and Cattle Company

Frank F. Sinon, Foreman, White Ranch, Little Horse Creek

E. C. Metcalf, Blacksmith, Wheatland

Charles H. Tolson, Porter, Cheyenne

J. E. Barnes, Butcher, Cheyenne |

Horn Jury

At the end of the

fifth ballot, two jurors voted for acquittal.

The jury then examined all of the testimony. After re-examination, the two hold-out

jurors voted guilty. Each later made statements to the effect that

although they liked Horn, they had no choice but to find him guilty. Later,

Gwendolene Myrtle Kimmell, Horn's romantic interest as

portrayed in the movies, accused in a statement appended to Horn's autobiography

some of the jurors of being rustlers.

According to Larry Bell, "Tom Horn: his life & Legend", University of Oklahoma Press, (2014),Horn kept up his braggadocio whistling from his jail cell at parishioner passing by on their was to

Sunday morning mass "Goodbye, My Honey, I'm Gone.""

On appeal, Horn's lawyers argued, among other things, that had not the two hold-out jurors

been improperly influenced

by comments that they may have overheard while

dining, the jury would have remained deadlocked. The head waiter of the hotel testified that guests of the hotel were

discussing the case when the jury was present. The two baliffs, who sat at either end

of the table in the hotel dining room when the jurors were served, testified that

they heard no improper comments from other diners in the hotel. Tolson, who sat

directly opposite the two jurors, testified

in similar fashion.

In August 1903, while his appeal was pending, Horn with another inmate of the jail, Jim McCloud, attacked Deputy

Proctor, broke into the Sheriff's office and stole an automatic pistol. Leslie Snow came upon the scene

and gave the alarm. In the meantime Horn and McCloud made it out onto the street with

McCloud and Horn heading in opposite directions. Horn first headed east on 19th Street one block

to Capitol, the Courthouse being on the corner of 19th and Ferguson [now Carey]. Horn then headed

north on Capitol and then east on 20th being chased by a passerby, O. M. Eldrich. Eldrich fired at

Horn and Horn attempted to fire the automatic at Eldrich. Apparently Horn was

unfamiliar with the safety on the automatic and was unable to fire the gun. Pedestrians then

overpowered Horn and he was returned to the jail. See next photo.

Tom Horn being escorted back to jail after escape attempt.

While awaiting the outcome of an appeal,

Horn spent his time braiding a rope, see photo below, and writing an autobiography. Additionally he busied himself

with correspondence. In March of 1902 he had complained to John Coble that except for Charlie

Irwin and Coble he had no visitors.

His appeal was denied on September 30, 1903. Following the denial of the appeal a flury of letter writing

resumed accusing those who testified of perjury. On October 31, Horn wrote Coble that one of his lawyer, Timothy Burke, has told him

he need affidavits proving he was no where near the Nickell homestead the day of the

murder. He was, he insisted at Alex Seller's ranch both that morning and at the end of the day. He

indicated to Coble that this could be confirmed by Dorrance Linscott and by Seller. Linscott did not respond to

Horn's letters and Horn did not know where Seller was. Writer's note: Seller's Ranch was at Toltec, North of Rock Creek about

60 miles as the crow flies from Iron Mountain. Soon an affidavit was produced in whch

Clarence D. Houck averred that Seller had admitted that Horn was there on the day in question.

Seller then came forward with an affidvait that the contents of the Houck

affidavit were untrue. By November Horn, seemed resigned to his fate. On

November 17 he wrote Coble:

Dear Johnnie:

Proctor told me that it was all over with me except

the applause part of the game.

You know they can't hurt a Christian, and as I am

prepared, it is all right.

I throuroughly appreceiate all you have done for me.

No one could have done

more. Kindly accept my thanks,

for if ever a man had a true friend, you have proven your-

self

one to me.

Remember me kindly to all my friends, if I have any

besides yourself.

|

Horn weaving rope

As preparations for the execution neared, fears arose

that friends would attempt to break Horn out of jail. Thus, extraordinary precautions were

taken to prevent another escape. The Courthouse was surrounded by Companies A and E of the

Wyoming National Guard. Other prisoners were placed on a lower floor of the jail, leaving Horn along

on the top floor. A curtain was placed over the window in Horn's cell preventing him from seeing the

construction of the gallows below and, more importantly, precluding the exchange of signals between Horn and

his friends. Deputy sheriffs were at every window. As a result of the turmoil, after the Horn case

was over, all future executions were moved to the State Penitentiary.

At the same time there began a flurry of legal efforts to convince

Governor Chatterton to spare Horn from the gallows. At the end of October, affidavits were presented

to the governor intended to indicate that there was new evidence, including allegations that the

murder was committed by a double. Other affidavits were presented that witnesses had admitted that

they had perjured themselves or had been offered bribes for perjured testimony. The Laramie

Boomerang reported on November 4, quoting the Denver Post, that the legal efforts

were weakening Horn's case:

Gradually the inside facts relating to the affidavits presented to Gov. Chatterton Saturday in

behalf of Tom Horn, the condemned murderer, and the methods employed to secure them are becoming

known. The Frank Muloch Affidavit is regarded as being absolutely worthless and if it has had any bearing

on the case at all it has had a tendency to weaken Horn's plea. It is so plainly evident that there never was a double of

Horn, except the one manufactured in this case, that the affidavit is regarded as a sort of boomerang.

Affidavits in support of

executive clemency were presented to Governor Chatterton that the person in the Scandinavian Saloon was a double for

Horn, a case of mistaken identity. Mulock contended that it was only a "fellow claiming

to be Horn" who made the confession in the Saloon (emphasis in Mulock letter to J. W. Lacey, Oct. 5, 1903). Governor Chatterton dismissed the affidavits noting that the affidavits were inconsistent with

other affidavits presented by the defense relating to the conversations.

The efforts of Miss Kemmell to save Horn were also down played by the Boomerang. The

presentation of Miss Kemmell by Horn's attorneys was regarded as a "bad move" in "the opinion of every one who has

followed the case, and especially those who have seen the woman." Miss Kimmell contended that

Vic Miller killed Nickell.

The Boomerang report concluded:

Joe LaFors [sic], who trapped Tom Horn into making the confession that he

killed Willie Nickell, ridicules the affidavits presented to the

governor Saturday. He says they contain all kinds of misstatements and that

their sole purpose is to save a man from hanging who not only is

guilty of the foulest of crimes but was convicted fairly.

After a trial by affidavits in front of the governor including one which suggested (but did not say) that

LeFors had been bribed not to investigate Miller, Governor Chatterton rejected them noting that

the contents would not have been admissible in a court of law.

As the date set for execution drew near, the appeals to the governor became more impassioned.

Governor Chatterton received a letter wrtten from Denver's Albany Hotel threatening death if

he did not commute the sentence. On the evening of the 18th, National Guardsmen stopped by a threat to shoot,

a group of horsemen approaching the courthouse on Eddy Street. On the morning of the 19th, a friend of

Horn's was overheard commenting, "These little tin soldiers will get all the misery they want tonight."

Crowds and soldiers on street near Courthouse.

On the afternoon and evening of November 19, Governor Chatterton turned down no fewer than

twelve appeals to delay the execution. Before 6:00 a.m. of the day set for the execution, the governor

was aroused from his bed with yet another appeal. He responded, "There is no use,

gentlemen. This execution will take place at the time set by the

law. I will not interfere in the case. This is final."

The invitations to the hanging were duly issued. The prosecution could invite twelve, Horn six. Kels Nickell was

denied an invitation. Roman Catholic and Episcopal priests visited with Horn, but Horn denied to

Charlie Irwin that he had gotten religion. Invitees reported to the rope barriers at the

courthouse at 7:00 a.m. On the roof, Sheriff Smalley's gatling gun stood guard. While waiting, one Denver Post reporter told the others

as to the number of executions he had attended. The executions were passť, he said. They were

no more emotional that "the killing of a rat." Later, it was discovered that the

stone-hearted reporter for the Post cried during the hanging.

Music this page:

Good-Bye, My Honey, I'm Gone.

Copyright, 1885, by W. A. Evans & Bro.

I had a girl, and her name was Isabella,

She ran away with another colored feller,

Chorus.

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone,

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone;

And I couldn't stay no longer;

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

One day in de middle of de month ob Januyear,

I rolled my dearie in my arms for to soothe her

But her heart was with another,

And she wouldn't let me love her;

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

Chorus.

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone,

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone;

And her heart was with another,

And she wouldn't let me love her;

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

I thought dis girl was de nicest little daisy,

'Till a dude came along from de roller rink so crazy;

And I hollered for a copper.

But he said, he couldn't stop her;

Good-bye. my honey, I'm gone.

Chorus.

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone,

Good-bye. my honey, I'm gone;

And I hollered for a copper.

But he said, he couldn't stop her;

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

I had a girl and she was a little lily,

Freddy came along and knocked her very silly;

And I hollered for a copper.

But he wouldn't run to stop her;

Good-bye. my honey, I'm gone.

Chorus.

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone;

And I hollered for a copper.

But he wouldn't run to stop her;

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

I forgot for to tell you her name was Mary Walker,

she wore de pants till she couldn't wear 'em shorter;

And I hollered for a copper.

But If said, he couldn't stop her;

Good-bye, my honey. I'm gone.

Chorus.

Good-bye, my honey. I'm gone,

Good-bye. my honey, I'm gone;

And I hollered for a copper,

But he said, he couldn't stop her;

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone.

This funny little girl was a dandy little runner,

Her name was Belva Lockwood, but the White Home was a stunner,

And I hollered for a copper,

Bur. he said, he couldn't stop her;

Good-bye. my honey, I'm gone.

Chorus.

Good-bye, my honey, I'm gone,

Good-bye. my honey, I'm gone;

And I hollered for a copper,

But he said, he couldn't stop

I know a man and he tried to coin a dollar.

His name is Uncle Sam. and he ought to get a collar,

For it wasn't worth a dollar.

And the ninety cents was holler;

Good-bye, my children, I'm done.

Chorus.

Good-bye, my children, I'm done.

Good-bye, ray children, I'm done;

For It wasn't worth a dollar.

And ninety cents was holler;

Good-bye, my children, I'm done.

Next Page: The Hanging and the aftermath.

|