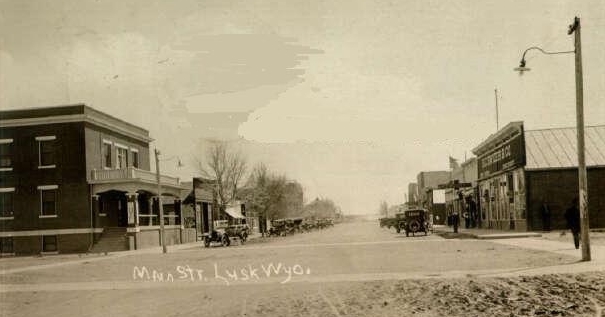

Lusk, circa 1918. Henry Hotel on left. The hotel later became the

Spencer Hospital.

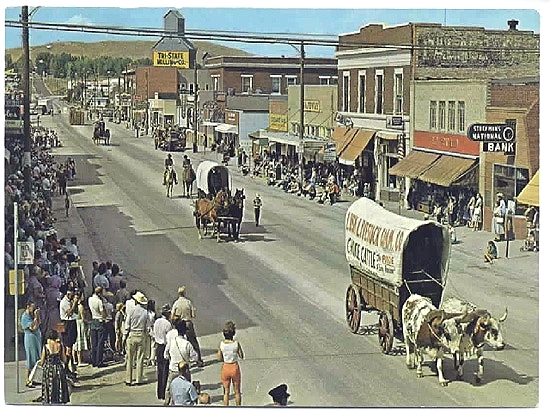

Annually, the citizenry of Niobrara County celebrate the "Legend of Rawhide." The

festivity, celebrated in conjunction with the county fair, includes not only a

pagent, but a parade down Main Street. The script for the

pagent was written in 1946 by EvaLou Bonsell "Bonnie" Paris. EvaLou is also noted as the

one who recovered Mother Featherlegs Sheppard's bloomers from the Number 10 Saloon in

Deadwood where they had been taken. The legend and the

pagent is of such importance that in the early 1960's there was a

movement to rename the town to "Rawhide."

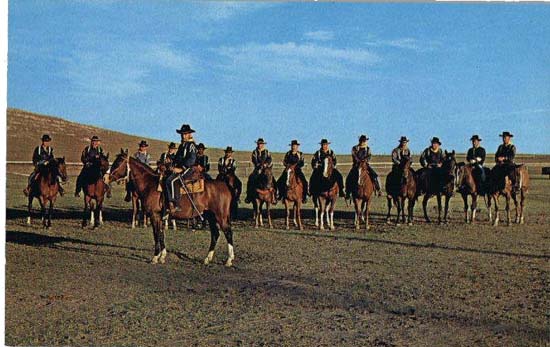

Legend of Rawhide Parade, 1950's

Festivities such as the County Fair go back to the formation of the county. The original Niobrara County Fair and

Race Association was formed in 1911. the first president of the Association was

Ralph Olinger (1885-1965), the son-in-law of Harry Snyder. Olinger served as

master of the Harmony Masonic Lodge. the county fair is now managed by the Niobrara

County Fair Board appointed by the Board of County Commissioners.

Potato Race, Lusk, 1908

A potato race was one in which cowboys with a lance or

spear race from the beginning of a course to a barrel or box at the opposite end of the course, stab a potato in the barrel, and

return to the finish line with the potato still on the spear. It is fair to

attempt to knock the potato off another rider's spear. It is a test of ridership and agility.

Other popular races at the time were "bed roll" and "boot" races. In the bed roll race, the cowboy would lay out his

bed roll on the ground about fifteen feet from his horse, use the saddle as a pillow, cover up with the blanket as if asleep,

and at the signal, get out of the bed roll, saddle the horse, roll up the bed roll putting it behind the saddle, and gallop

off the requisite distance without the bed roll coming undone. If the bed roll came undone, he was disqualified. In the "boot race,"

all of the cowboys took off their boots which were mixed up in a big pile. On the signal all would race to the pile, find

their boots, put them on, mount their horses, and race the requisite distance.

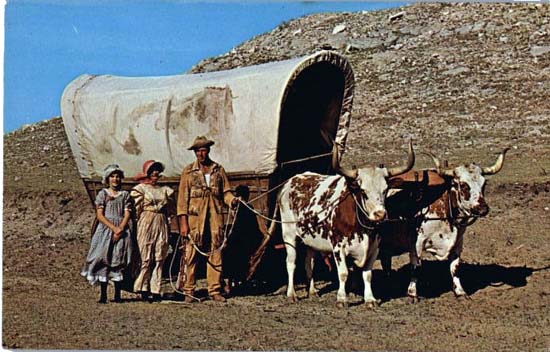

According to the "Legend of Rawhide, a wagon train passed through the area in June of 1849 on the

way to the gold fields of California. A young man in the train, having vowed to

kill the first Indian he saw, shot and killed an Indian maiden. The Indians

were, quite naturally, upset about this turn of events and demanded that the culprit be

turned over to them. The wagon party, not believing that one of their members would

have done such a thing, refused. The Indians attacked and were repelled. The Indians

attacked again and then unexpectedly withdraw with wild war-whoops; for the

young man had given himself up to save the train. The Indians skinned him alive, thus,

accounting for the quite aprocryphal naming of nearby Rawhide Creek and

Rawhide Buttes. In should be noted that Rawhide Creek bore its name at the time of

Sage's tour of the area in the early 1840's. Another explanation for the naming of Rawhide Creek and Buttes is that

the name originated with the early mountain man name for a dressed out beaver pelt -- rawhide.

A wagon used in the Legend of Rawhide.

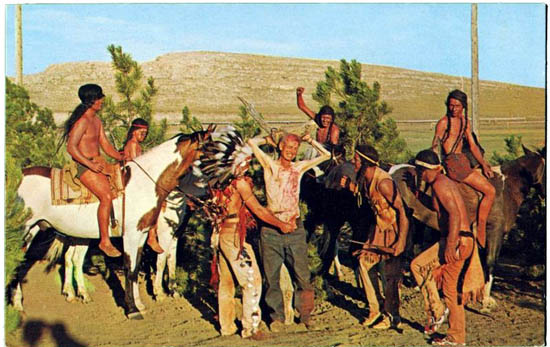

Indians Skinning the Young Man alive, Legend of Rawhide.

The Cavalry, Legend of Rawhide.

But before the reader dismisses the legend out of hand, there may be some basis for the story. William F. Drannan (1832-1913) in his

1910 account, Chief of Scouts as Pilot to Emigrant and Government trains Across the Plains of

the Wild West of Fifty Years Ago, recounted an incident in Nebraska in 1850:

Bridger and I rode down to where the emigrants were in camp, and we

found the most excited people I ever saw in my life. They had passed

through one of the most terrible experiences that had ever occurred on

the frontier. There were thirty wagons in the train, and they were all

from the southeastern part of Missouri, and it seemed that there was one

man in the train by the name of Rebel who at the time they had left

home had sworn that he would kill the first Indian he came across. This

opportunity occurred this morning about five miles back of where we met

them. The train was moving along slowly when this man "Rebel" saw a

squaw sitting on a log with a papoose in her arms, nursing. He shot her

down; she was a Kiawah squaw, and it was right on the edge of their

village where he killed her in cold blood. The Kiawahs were a very

strong tribe, but up to this time they had never been hostile to the

whites; but this deed so enraged the warriors that they came out in a

body and surrounded the emigrants and demanded them to give up the man

who had shot the squaw. Of course, his comrades tried not to give him to

them, but the Indians told them if they did not give the man to them,

they would kill them all. So knowing that the whole train was at the

mercy of the Indians, they gave the man to them. The Indians dragged him

about a hundred yards and tied him to a tree, and then they skinned

him alive and then turned him loose. One of the men told us that the

butchered creature lived about an hour, suffering the most intense

agony. They had just buried him when we rode into the camp. The woman

and some of the men talked about the dreadful thing; one of the men said

it was a comfort to know that he had no family with him here or back

home to grieve at his dreadful death.

[Writer's note: The biographer of Kit Carson, Harvey L. Carter, dismisses at least part of

Dannan's accounts as being a "tissue of lies." In contrast, Professor Edward A. Stasack formerly

of the University of Hawaii and now a resident of Arizona, has noted new evidence

confirming the most controversial of Dannan's claims, that he was a

young companion of Kit Carson and was on one of the Fremont expeditions.]

Panoramic view, Lusk, 1920

In the top photo above, across the street from the brick hotel, is H. C. Snyder & Co.,

Groceries (on the right in top photo, on the left in panoramic view). Next door is the Toggery.

Note the change in the street

light.

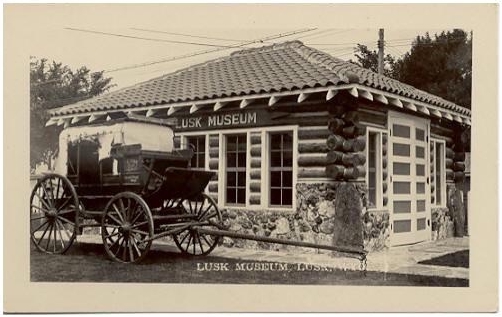

Four-horse Deadwood stage in front of

Lusk museum, undated

The Museum was constructed as a WPA project intended only to house the coach. The coach, donated by Russell Thorp, Jr., is the center piece of the museum, now located on South Main in the former Armory.

Lusk Stagecoach Museum, 2005. Photo by Geoff Dobson

The present museum originally was the National Guard Armory constructed in 1927. Other exhibits also relate

to the Cheyenne-Black Hills Stage Road include Mother Featherlegs' bloomers and a stove from the

"new" Hat Creek Stage Station. In the Spring of 2002, the stove became a source of a minor

cause celebre when the Wyoming State Museum in Cheyenne threatened to take the stove away for a pioneer exhibit. The stove is

somewhat unique in that it has a reservoir for hot water. Other exhibits include dinosaur bones, a safe from the Black Hills stage,

assorted wagons and a wonderous collection of photographs. Behind the

museum is the old Lusk Free Lance newspaper office.

Lusk Free Lance printing office,

Lusk Stagecoach Museum, 2005. Photo by Geoff Dobson

The Free Lance was printed by James E. Mayes, who was at one time

also an owner of the Lusk Herald in its formative years. The Free Lance also printed the Van Tassell Booster. Later the

paper was run by Arthur Franklin Vogel. In 1957, the Free Lance was bought out by the Lusk Herald.

Lusk continued on next page.

|