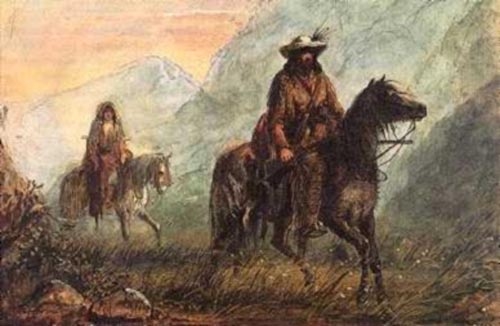

Bourgeois and Squaw, Alfred Jacob Miller, 1837.

The above painting depicts Joseph Reddeford Walker (1798-1876).

A bourgeois was a supervisor of other trappers. As noted on the previous page, there were three types of

trappers, those who were employees of the fur company and under the supervision of

the bourgeois, others who in exchange for outfitting by the company, contracted to sell all

their pelts to the company, and finally "free" trappers who provided their own outfits and were

not under any contractual obligation. Walker was a member of

the Bonneville and Fremont Expeditions and was also the first sheriff in

Independence, Missouri. With his familiarity of the west, including the

Sierras, he attempted to warn the Donner Party about the possible consequences of their

late departure. His warning was dismissed, however, as that of an "ignorant Missouri puke."

The most famous of the mountain men, James Felix Bridger (1804-1881), was born in Richmond, Virginia,

the son of an innkeeper. In addition to serving as a guide, he is credited for discovering

the Great Salt Lake, South Pass, and Bridger Pass. He visited Yellowstone and acted as a guide for Albert Sidney Johnston.

Additionally, he acted as a guide for Gen. G. M. Dodge's survey parties laying out the line for the Pacific Railroad. He was the son-in-law of

Chief Washakie. In the 1860's he returned to Westport, Missouri (now a part of Kansas City),

where he had a farm near present day 103rd St. and State Line, and operated with his son-in-law, Albert Wachsmann,

an outfitting business at present day 504 Westport Rd. The building still stands and is occupied by

a restaurant.

A. J. Shotwell, a private from Co. F, Eleventh Ohio Cavalry, recalled Bridger from an 1865 eight-day shared ride from

Ft. Laramie to Missouri. The two, along with a second soldier had intended to catch the eastbound Overland

Stage at Julesburg. Unfortunately, the stage was fully booked for the next ten days. Thus, the

three hitched a ride with an empty wagon train heading east. At each of the road ranches along

the way, Bridger was recognized, welcomed and money would not be accepted. Shotwell described Bridger as:

[W]ell proportioned form of slender mold, about six fee high -- probably a little less, possibly a trifle more, straight

as an Indian and quick in movement, but not nervous or excitable; in weight, probably one hundred and sixty pounds, with an eye as pierceing as the eye of an eagle; that

seemed to flash fire when narrating an experience that called out his reserve power. There was

nothing in his costume or deportment to indicate the heroic spirit that dwelt within -- simply a plain,

unassuming man, but made of heroic stuff, ever inch!

At the 1835 Rendezvous at the confluence of Horse Creek and the Green River, Dr. Marcus Whiteman

removed, to the amusement and amazement of the ensembled

multitudes, a three inch arrow or spearhead that had been lodged in Jim Bridger's shoulder for the

preceeding three years. The Reverend Samuel Parker in his 1838 self-published

Journal of an Exploring tour Beyond the Rocky Mountains, Under the Direction of the

A. B. C. F. M. Performed in the Years 1835, '36, and '37 described the

operation:

While we continued in this place, Doct. Whitman was called to perform some

very important surgical operations. He extracted an iron arrow, three inches long, from

the back of Capt. Bridger, which he had received in a skirmish three years

before, with the Blackfeet Indians. It was a difficult operation in consequence

of the arrow being hooked at the point by striking a large bone, and a

cartilaginous substance had grown around it. The doctor pursued the operation

with great self-possession and perserverance; and Capt. Bridger manifested equal firmness. The

Indians looked on while the operation was proceeding with countenances indicating wonder, and

when they saw the arrow, expressed their astonishment in a manner peculiar to themselves.

The skill of Doct. Whitman, undoubtedly made upon them a favorable impression. He also took

another arrow from the shoulder of one of the hunters, which had been there two

and a half.

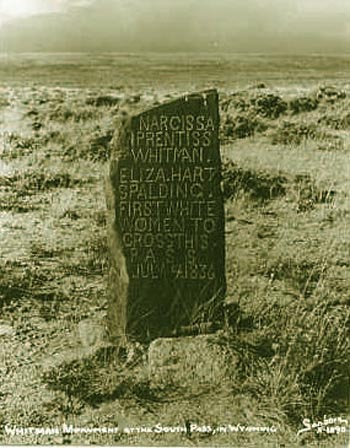

Monument to Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding Hart, South Pass, Wyo.,

photo by William P. Sanborn

Monument to Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding Hart, South Pass, Wyo.,

photo by William P. Sanborn

[Writer's note: "A. B. C. F. M." denotes the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions,

which sponsored Congregational and Presbyterian missions.]

Bridger had received the arrow following the 1832 Rendezvous. He and Thomas Fitzpatrick were trapping

along the Jefferson Fork of the Missouri and had been followed by trappers led by Andrew Drips and Henry

Vanderburgh who, apparently, hoped to steal Bridger and Fitzpatrick's territory. Realizing that

they were being followed Bridger led the followers into Blackfoot territory. Dr. Hebard and E. A.

Brininstool in their The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland

Routes into the Northwest, and the Fights with Red Cloud's Warriors, Arthur H. Clark Company, 1922, described

what happened:

The expected happened. The rivals were attacked on a stream which was one of the

sources of the Jefferson and Vanderburgh was killed, the Indians stripping his flesh from the bones and

throuwing the skeleton into the river. Bridger himself did not escape unscathed, for soon after he was

attacked by Indians of the same tribe. In the fight which folloed, Bridger and the

chief met in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, during which the trapper received two severe arrow wounds in the

back, and was also felled to earth by a blow from his own gun, which the chief wrenched from his grasp.

Dr. Whitman returned

to the 1836 Rendezvous accompanied by his new bride, Narcissa Whitman, one of the

first two women to cross the continent to Oregon. The marriage was motivated at least in

part by the desire of both Dr. Whitman and Narcissa to become missionaries to the

Indians. The Board of Commissioners required missionaries be married. Thus, in

what may have been a marriage of convenience, the two were married in February 1836. Mrs.

Whitman, an alumna of Emma Willard's "Female Seminary," was "fine of voice." The last

hymn of the marriage ceremony was the maudlin Yes, My Native Land! I Love Thee. As the

singing continued, the congregation broke up in tears. The only one left

singing by the time of the final verse was the new Mrs. Whitman. The fifth verse:

In the deserts let me labor,

On the mountains let me tell

How he died--the blessed Savior--

To redeem a world from hell!

Let me hasten, Let me hasten,

Far in heathen lands to dwell;

Let me hasten, Let me hasten,

Far in heathen lands to dwell.

The Whitmans were later killed by Indians at their mission in Oregon. The hymn was also

sung by Mormon emigrants departing Britain as part of the Perpetual Emigrating

Fund Company.

Narcissa Whitman

Narcissa Whitman

The procedures followed by the American Fur Company on the Rendezvous were described by

Dr. Whitman's fellow missionary, Henry Harmon Spalding (1803-1874) in an 1836 letter:

The company with which we Journeyed consisted of about 90 men, and 260 animals, mostly mules,

heavy loaded. At this camp we found about 300 men, and three times the number of animals,

employed by the Fur Company in taking furs, and about 2000 Indians, Snakes, Bonnaks, Flatheads,

and Nez Perces. Captain Steward [sic], an English gentleman of great fortune, and Mr. Seileim, a

German, traveled with us for discovery and pleasure, -- The order of the camp was as follows:

rise at half past 3, A. M. and turn out animals, march at 6, stop at 11, catch up and start

at 1, P. M., camp at 6, catch up and picket animals at 8; a constant guard night and day.

The intervals were completely taken up in taking care of animals, getting meals and seeing

to our effects, so that we had no time for rest from the time we left one post till we reached

another. When we reached this place, not only our animals but ourselves were nearly exhausted.

Our females endured the fatigues of the march remarkably well. Your ladies who ride on

horseback 10 or 12 miles over your smooth roads, and rest the remainder of the day and week,

know nothing of the fatigues of riding on horseback from morning till night day after day for

15 or 20 days, at the rate of 25 and 30 miles a day, and at night have nothing to lie on but

the hard ground. Truly we have reason to bless our God that our females are alive and enjoying

comparatively good health. The Fur Company showed us the greatest kindness throughout the whole

journey. We have wanted nothing which was in their power to furnish us.

The Reverend Spalding established his mission at Lapwai, Idaho, near present-day Lewiston. Following the massacre of

the Whitmans, the Spaldings evacuated to Oregon and, over, Spalding's protests, the A. B. C. F. M.

ordered the mission abandoned. Eliza Spalding died January 7, 1851.

At the 1837 Rendezvous, Capt. Sir William Drummond Stewart presented Bridger with a

replica suit of armor brought from Britain. Bridger, drunk, proceeded on horseback to clank around the rendezvous grounds in the armor.

Sir William, a veteran of Waterloo and an excellent marksman, attended each rendevous from 1833 to 1837,

bringing nothing but the finest provisions. Indeed, Sir William required 19 carts and 3 wagons together with a retinue of approximately

50 to meet his needs.

Bridger, drunk, 1837 Rendezvous, pencil sketch by Alfred Jacob Miller.

Bridger, drunk, 1837 Rendezvous, pencil sketch by Alfred Jacob Miller.

The 1837 Rendezvous was attended by more than 2,000 trappers, traders and Indians. Styles had already begun to change and top money

was not received for the furs. The Miller paintings are about our only accurate depictions of the

early mountain men. Later pictures by Remington and others were basically pictures of late 19th Century

trappers or from imagination.

Rufus B. Sage described the early mountaineers:

His skin, from constant exposure, assumes a hue almost as dark as that of the Aborigine,

and his features and physical structure attain a rough and hardy cast. His hair, through inattention, becomes long,

course, and bushy, and loosely dangles upon his shoulders. His head is surmounted by a low crowned

wool-hat, or a rude substitute of his own manufacture. His clothes are of buckskin,

gaily fringed at the seams with strings of the same material, cut and made in a fashion

peculiar to himself and associates. The deer and buffalo furnish him the required covering

for his feet, which he fabricates at the impules of want. His waist is encircled with a belt

of leather, holding encased his butcher-knife and pistols -- while from his neck

is suspended a bullet-pouch securely fastened to the belt in front, and beneath the right arm hands a

powder-horn transversely from his shoulder behind which, upon the strap attached to it, are affixed his

bullet-mould, ball-screw, wiper, awl, &c. With a gun-stick made of some hard wood, and a good

rufle, placed in his hands, carrying from thirty to thirty-five balls to the

pound, the reader will have before him a correct likeness of a genuine mountaineer, when fully equipped.

One of the more

distinctive [pardon the pun] attributes of the early mountain men was their aroma.

As noted by Jim Clyman in Journal of a Mountain Man, the early trappers not only refused to change their clothes but would

wipe their knives and hands on their clothes after eating or after skinning animals:

"...Naturally, if some of this mixture (speaking of castorium) spilled on

their hands, they wiped it on their buckskins; they didn't stop there, but

wiped their greasy hands on their skins after eating, and wiped off the

blood when skinning. The resulting color and flavor of the skin was not

the clean gold of fresh-tanned hides.

Instead, it was, as Don Berry says, "black. Dirty

black, greasy black, shiny black, bloody black, stinky black. Black."

[Writer's note: Castorium, an odoriferous oily secretion of the beaver, used in the making

of perfume.]

Of course, the trappers may not have been able to change their clothes. They often had but one set.

Thus, Captain Lee Humfreyville in his 1899 Twenty Years Among Our Hostile Indians noted an incident

with Jim Bridger:

During that winter, Bridger's suit of buckskin clothing (and it was all he had)

became infested with vermin, and in despair he at length asked me how he could get rid of them.

I told him if he would take off his buckskin jacket and breeches and wrap himself in a buffalo

robe, I would undertake to rid his clothes of the pests. He thereupon took his clothing off and turned it

inside out. After spreading the garments on the ground, I poured a ridge of gunpowder down the seams of

the suit, and touched it off. It burned the vermin, and it also burned the buckskin clothing

badly. On the seams of the leggins I had sprinkled so much powder that it burned the

garments to charred leather. They were drawn up short at the seams, and after being turned, each leg curled up unitl

it looked like a half-moon. Bridger looked at me for a moment in great disgust,

and then with a big oath said: "I am a-goin' to kill you for that." I was

afraid he would make his threat good, for he was certainly very indignant. I laughed at him, and

taking hold of the leggins I streched them into the best shape possible, but the leather was burned to brittleness and broke at the slightest

touch. Bridger did not forgive me for this until two or three days, during which time he was

compelled to go about in a buffalo robe until another buckskin suit could be procured.

Jim Baker, undated

Jim Baker, undated

There was a value or purpose, however, to wiping the grease and other substances on the clothing.

David Lavender in Bent's Fort described the trapper's clothing:

"Down to his shoulders hung the hunter's hair, covered with a felt hat

or perhaps the hood of a capote. He liked wool clothing, for it would

not shrink as it dried and wake him, when he dozed beside the fire, by

agonizingly squeezing his limbs. But wool soon wore out and he then clad

himself in leather, burdensomely heavy to wear, fringed on the seams with

the familiar thongs which were partly to decorate but most utilitarian, to

let rain drip off the garment rather than soak in, and to furnish material

for mending. Further waterproofing was added by wiping butcher and eating

knifes on the garments until they were black and shiny with grease. Upper

garments might be pull-over type or cut like a coat, the buttonless edges

folded over and clinched into place with a belt. No underclothes were worn,

just breechclout. In extreme cold a Hudson's Bay blanket or a buffulo robe

was draped Indian-wise over the entire costume."

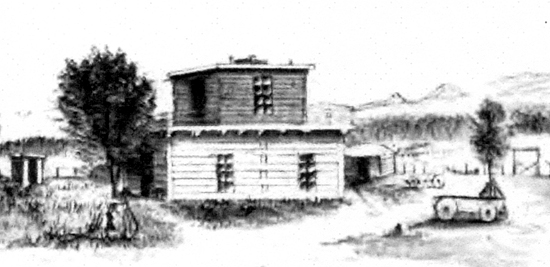

Some of the early mountain men never did get used to modern hygene. Jim Baker (1918-1898), who

served in the Fremont Expeditions, ultimately settled down in a two-story log

blockhouse between Dixon and Savery.

Baker Cabin, Dixon, Wyoming, 1899.

As noted above, the cabin was originally constructed between Dixon and Savery. In 1917 the State Legislature

appropriated $750.00 to purchase the cabin. It was moved to Frontier Park in Cheyenne.

Baker Cabin, Frontier Park, Cheyenne, July 1920.

Photo by Lt. Flag A. Drewry, courtesy of Mary Carol Schrupp.

The above photo was taken by Lt. Drewry while he was on temporary duty for ten days at Fort D. A. Russell.

He was at D. A. Russell for examination for commissioning in the regular army. He was successful.

In 1976, the cabin was again moved from Cheyenne to Savery "on loan"

from the Wyoming State Museum. The various moves probably account for the concrete foundation visible in

the next photo.

Baker Cabin, Savery Museum, 2003, photo by Geoff Dobson

In the late 1800's, Baker was as famous as Jim Bridger. His stories were quoted by numerous

writers including Mark Twain and Theodore Roosevelt. One of the more famous was his observations

on blue jays:

You may call a jay a bird. Well, so he is, in a

measureóbecause he's got feathers on him, and don't

belong to no church, perhaps; but otherwise he is

just as much a human as you be. And I'll tell you

for why. A jay's gifts, and instincts, and feelings,

and interests, cover the whole ground. A jay hasn't

got any more principle than a Congressman. A jay

will lie, a jay will steal, a jay will deceive, a jay will

betray; and four times out of five, a jay will go back

on his solemnest promise. The sacredness of an

obligation is a thing which you can't cram into no

blue-jay's head.

In 1895, Baker and John Albert, another early mountain man, were

invited to serve as marshals for Denver's very first Festival of Mountain and

Plain. The committee put him up in one of Denver's finest hotels. When it was

suggested he might like to take a bath, he informed them he did not need one -- he had one this

year. Additionally, he refused to sleep in the bed, preferring the floor, and

refused to use the flush toilet, preferring the alley behind the hotel.

Not all mountain men abstained from indoor plumbing. William Sublette's partner, Robert Campbell, was financially the

most sucessful of all the mountain men. Campbell moved from furs, to supplying the Army during the

Mexican War, to steamboats, railroads, hotels, and real estate, becoming a millionaire in the process.

Robert Campbell House, St. Louis, 2003, photo by Geoff Dobson

Campbell's house

on 1508 Locust Street, St. Louis, was one suitable for entertaining the President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant. Others

who passed through its elegant parlors included Father DeSmet, Gen. Sherman, Gen Harney, Washington Irving, as well as

Indian chiefs. The chiefs were allegedly served fire water from a silver punch bowl.

Another attribute of mountain men was their language. The Reverend Parker noted of the

mountain men:

In the absence of all those motives which they would feel in moral and

religious society, refinement, pride, a sense of the worth of character,

and even consceince, give place to unrestrained dissoluteness. Their

toils and privations are so great, that they are not disposed to take

upon themselves the labor of climbing up to the temple of sceince. And yet they

are proficients [Sic] in one study, the study of profuseness of language in

their oaths and blasphemy.

Moses "Black" Harris, an early Black

mountain man was a part of the Ashley expeditions to Yellowstone between 1822 to 1826.

Harris is credited as also assisting in the location of the site for Fort Laramie and for helping in its

original construction. Alfred Jacob Miller described Harris as being a wiry, muscular man with a leathery

cordlike blue-black skin as if burned by gunpowder. His epitaph reads:

HERE LIES THE BONES OF OLD BLACK HARRIS

WHO OFTEN TRAVELED BEYOND THE FAR WEST

AND FOR THE FREEDOM OF EQUAL RIGHTS,

HE CROSSED THE SNOWY MOUNTAIN HEIGHTS

WAS A FREE AND EASY KIND OF SOUL,

ESPECIALLY WITH A BELLY FULL.

Like many a mountainman, Harris was also known as a raconteur. To him is now

attributed the story of the petrified birds, sitting in the petrified trees with

petrified leaves in Yellowstone. The story became more and more elaborate with retelling

by others including Jim Bridger, Legh Freeman (see Ghost Towns) and

Anson Mills, until finally the birds were singing petrified songs.

The era of the mountain men came to a rapid decline. Less than 140 whites attended the 1840 Rendezvous and, with the expense of

bringing goods by wagon from St. Louis, it was announced that no further rendezvous would be held.

Notwithstanding that 1840 represented the last Rendezvous, in August 1843, Sir William sponsored a reunion of sorts

on the Green River near Fort Bridger. There, trappers and Indians gathered for

three days of horse racing, ball games, drinking, and story-telling.

Sir William provided some $500 worth of prizes for the fastest rider.

The winner was a naked Shoshoni known as "Indian Tom," riding a horse owned by

William Sublette. Indian Tom's only item of clothing was a red handkerchief.

Next page: The End of the Fur Trade and the Trapping Era.

|