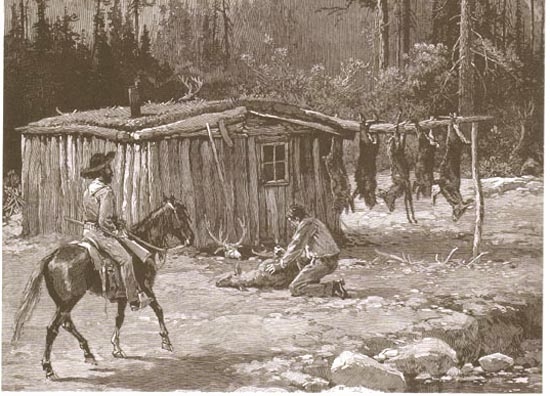

Trappers' Cabin, Harper's Weekly, 1890, drawing by Charles Graham

The picture is a fairly accurate depiction of an early cabin as would have

been constructed by French-speaking trappers from Missouri. The French were referred to by

one of Ashley's company, Jim Clyman, as "St. Louis gumboes." The cabin or

poteaux en terre, "posts in the ground," was built by digging a trench about two

feet deep and placing logs upright in a pallisade to form the walls. The spaces between

the logs would be filled with bousillage, a mixture of clay and grass or deer hair. Note the sod roof. The "window" in

the door would probably have been made of paper soaked in lard. The typical log cabin with horizontal logs, a

maison de pieces sur pieces,

was used by Anglo-Americans. The advantage of a poteaux en terre was that it could be construct by

one man. Construction of an Anglo-Saxon cabin required two men.

The end of the rendezvous system, did not mean the

end of trapping or of furs. Supplies were provided to trappers and furs purchased at various forts

established by the fur companies such as Fort William established by Sublette and Campbell, Bent's Fort in Colorado, or Fort Pierre operated by

the American Fur Company. A new emphasis was placed on buffalo robes as a result of the loss of demand for

beaver pelt. Beaver fur prices on the east coast fell from $4.50 a pound in 1832 to $2.50 a pound by 1840. But at the

same time buffalo robes doubled in value. Thus in 1840, some 100,000 robes came into St. Louis.

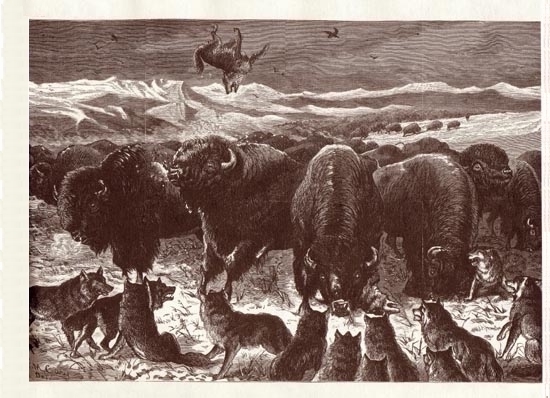

Buffalo Bulls Protecting Their Herd, W. M. Cary, Harper's Weekly, 1873

Wolves would follow buffalo herds, picking off calves or the elderly. The wolves were, however,

not a match for the bulls who could easily with their horns, as illustrated in the woodcut, flip a wolf into the air and then trample the

wolf to death. The real decimation of the buffalo population, however, did not start until the

1870's when wholesale slaughter began.

Captain Sir William Drummond Stewart, painting by Alfred Jacob Miller.

Captain Sir William Drummond Stewart, painting by Alfred Jacob Miller.

Alfred Jacob Miller followed Sir William to the Stewart Family estate, Murthly Castle in Pirthshire. There Sir William

set up a studio for Miller where many of the paintings by Miller of fur trapping days were painted. Accompanying

Sir William to Scotland were several American Bison and several American Indians who acted as game keepers.

The Indians would occasionally get drunk and would then hitch the bison to Sir William's carriage and take it through

town. A creole half breed acted as Sir William's butler. It was a combination of peculiarities of

English Common Law and personal tragedy that enabled many of the paintings to be returned to the

United States. Murthly Castle was entailed. Dating to the reign of Edward I it was not unusual for

estates to be held in "fee tail" under the principles of primogenture; that is, an estate held in

fee tail would descend to the oldest son of the original owner. The son, however, would hold the

estate only for his life and could not mortgage to convey the property. Upon his death, the estate would then descend to

his oldest son, and so on in perpetuity by action of law, thus insuring that the property would always be held within the family. The ownership of

estates in such a manner was central to the plots of Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights and

Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Entailed estates were abolished in England in 1925, see

Law of Property Act (15 & 16 Geo. 5, ch. 20, § 131), but not abolished in Wyoming until 1939.

Sir William before coming to America got into a family dispute whereby he vowed he would never again

sleep under the roof of Murthly Castle. His older brother, John, 6th Baronet of Murthly, died childless and, thus,

the estate and title descended to Sir William. Although Sir William returned to Scotland, he maintained

his vow and lived at first in a game keeper cottage. Later he had an extension built onto

the castle in which he would sleep. Servants were instructed to awaken him if he ever fell asleep under

the orginal roof. By an early unhappy marriage, Sir William had one son, George, to whom in

normal line of succession the tile and the estate would descend. George, however, at the time of the

Battle of Balaclava during the Crimean War was a member of the 13th Hussars remembered in Alfred,

Lord Tennyson's tribute. George was one who did not return:

THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

|

1.

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!

"Charge for the guns!" he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

2.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!"

Was there a man dismay'd?

Not tho' the soldier knew

Someone had blunder'd:

Their's not to make reply,

Their's not to reason why,

Their's but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

* * * *

5.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro' the jaws of Death

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

6.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made,

Honor the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred.

|

Sir William was not, however, completely childless, having had a son by a lady saloon keeper

in America. In his will, he left the estate to that son, Frank Nichols. The estate being entailed, however,

could not be left to an illegimate son. Thus, cousins inherited the castle, but the contents, being personal

property, were not entailed and went to Nichols. In an act of revenge to his cousins, Nichols cleaned the castle out and sold the paintings and other

items at auction in Endinburgh. There, many items were purchased by Americans and returned

to the United States. The bisons made their way to a local zoo where their descendants continue to

live.

In addition to Sir William Stewart, other members of the British peerage conducted early expeditions to the West. Among the more

notable was Sir St. George Gore's 1855-56 hunting trip out of Fort Laramie guided by Jim Bridger. Bridger was paid $750 for his services.

Sir St. George, accomanied for part of the journey by William Wentworth-Fitzwilliam (later the Sixth Earl of Fitzwilliam of Irland, Fourth Earl Fitzwilliam of England), did it up in

fine style with 40 attendants (including one individual whose function was to tie fishing flies),112 horses, 12 yoke of oxen, 6 wagons, 23 wheeled carts, 75 shooting rifles, 14 dogs, china, crystal, linens,

and a collapsible brass bed used in a green and white striped tent in whch, much to the consternation of Jim Bridger, his lordhip would

sleep late. Fitzwilliam later was to be the owner of the largest private "house" in Britain, a modest little structure with

a 600 foot long facade and 200 rooms. On the trip, 6,000 bison, 1,600 elk and 105 grizzlies were killed.

At Fort Union, Sir St. George, in a dispute relating to the sale of some of the equipment,

ordered everything burned except the arms and alcohol. While the wagons and

carts burned, the spectators consumed the alcohol. The last item thrown into the confligration was the

expedition journal. The expedition continued, however, until it came to an unexpected halt

near present day Sundance when the Sioux stole the expedition's horses, arms and

clothes. As a result, Sir St. George offered to raise a private army to do to the Sioux what he did to

the Bison. The American Army refused the offer.

In 1874, Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin, 4th Earl of Dunraven (See Yellowstone), toured the Upper Yellowstone. The dapper Dunraven, a

noted world traveler and war correspondent, with Texas Jack Omohundro as his guide, toured Yellowstone. Two years later

his account of his travels was published as Dunraven's The Great Divide: A Narrative of Travels in the

Upper Yellowstone in the Summer of 1874. With Maps and numerous

striking full page-Illustrations by Valentine W. Bromley. The book was

an immediate success. Thus, at least among the very wealthy, it became almost de regueur to take

extensive hunting trips to the American West. Among those who came to Wyoming, as discussed on later pages,

were Sir Horace Plunkett and Moreton Frewen and his brother Richard Frewen. Dunraven established a

hunting preserve and hotel at Estes Park, Colorado, and Frewen entertained the wealthy with

elaborate hunting trips from his log castle on Powder River.

For the most part, trappers had a short life expectancy. James O. Pattie (1804-c1850) in his

1831 Personal Narative recounted his trapping adventures between 1827 and 1830 through the Rockies and to

California. He observed that of 116 men who set out from St. Louis in 1824, by 1827 most were dead:

Some had died by lingering diseases, and others by the fatal ball or

arrow, so that out of 116 men, who came from the United States in 1824,

there were not more than sixteen alive. Most of the fallen were as true

men, and as brave as ever poised a rifle, and yet in these remote and

foreign deserts found not even the benefit of a grave, but left their

bodies to be torn by the wild beasts, or mangled by the Indians. When I

heard the sad roll of the dead called over, and thought how often I had

been in equal danger, I felt grateful to my Almighty Benefactor, that I

was alive and in health. A strong perception of the danger of such courses

as mine, as shown by the death of these men, came over my mind, and I

made a kind of resolution, that I would return to my home, and never

venture into the woods again. Among the number of my fallen companions,

I ought not to forget the original leader of our company, Mr. Pratte,

who died in his prime, of a lingering disease, in this place.

[Writer's notes: Mr. Pratte, Sylvestre Sebastien Pratte, born 1799. Pratte is believed to

have died along the headwaters of the Platte River in 1827 or 1828. Pratte was the son of Bernard Pratte a partner in

Pratte, Chouteau and Company, agents for the American Fur Company.]

James Pattie's father, Sylvester Pattie, was on the expedition with his son. The elder Pattie died

in a Mexican prison when the Patties' passport was not accepted by a local

commander. Other trappers lost their lives to Indians and wild animinals.

Jacques LaRamee [as previously observed, possibly Missouri free trapper Louis Lorimier, Jr.], after whom the river, the mountain, the county, the fort and the city are named,

disappeared to do beaver trapping

along a tributary of the Platte. Bridger in 1868 told John Hunton that Bridger had been a part of the

1821 search party which found only a half completed cabin and a broken beaver trap. Bridger indicated that

two years later he was told by the Arapaho that they had killed LaRamee and

placed his body under the ice behind a beaver dam.

Three of the five Sublette Brothers died early: Pickney was killed by the

Blackfeet at the Battle of Pierre's Hole in 1832;

Milton died of a leg infection at Fort Laramie after several amputations; and Andrew died as a result

of being mauled by a grizzly in California. Andrew was doing battle with a grizzly when a second grizzly came out

of the woods. Notwithstanding that Andrew's gun was out of amnuition, in a fierce battle he

was able to dispatch both grizzlies with a knife. Andrew and his dog, however, were badly

mauled. Mortally wounded, Andrew lingered for a while in his bed. His faithful dog stayed by the bedside until Andrew

expired. The dog followed his master's body to the grave side. There the dog stayed, refusing to

leave, and refusing drink and food until he too died.

Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Strong Smith was also attacked by a grizzly. Jim Clyman described the

surgery which may have saved Smith's life (Punctuation, capitalization at beginings of sentences, and paragraphing have

been added for purposes of clarity. Original spelling and mid-sentence capitalization are as in

original.):

The Crow Indians being our place of destination, a half Breed by the name of

Rose who spoke the crow tongue was dispached ahead to find the Crows and

try to induce some of them to come to our assistance. We to travel directly

west as near as circumstances would permit. Supposing we ware on the waters

of Powder River, we ought to be within the bounds of the Crow country.

Continueing five days travel since leaveing our given out horses and

likewise Since Rose left us.

Late in the afternoon while passing through

a Brushy bottom, a large Grssely came down the vally, we being in single file

men on foot leding pack horses. He struck us about the center. Then turning,

ran paralel to our line.

Capt. Smith being in the advanc. He ran to the open

ground and as he immerged from the thicket, he and the bear met face to face.

Grissly did not hesitate a moment but sprung on the capt, taking him by the

head. First pitcing sprawling on the earth, he gave him a grab by the middle.

Fortunately cathing by the ball pouch and Butcher Kife which he broke, but

breaking several of his ribs and cutting his head badly.

None of us having any sugical Knowledge what was to be done, one Said, "come take hold," and he

wuld say, "why not you?" So it went around. I asked Capt what was best. He said,

"One or 2 for water and if you have a needle and thread git it out and sew

up my wounds around my head," which was bleeding freely. I got a pair of

scissors and cut off his hair and then began my first Job of dessing wounds.

Upon examination, I, the bear had taken nearly all his head in his capcious

mouth, close to his left eye on one side and clos to his right ear on the

other, and laid the skull bare to near the crown of the head, leaving a white

streak whare his teeth passed. One of his ears was torn from his head out to

the outer rim. After stitching all the other wounds in the best way I was

capabl and according to the captains directions, the ear being the last. I

told him I could do nothing for his Eare. "0 you must try to stich up some

way or other," said he. Then I put in my needle stiching it through and

through and over and over, laying the lacerated parts togather as nice as

I could with my hands.

Water was found in about ame mille, when we all moved

down and encamped. The captain being able to mount his horse and ride to

camp, whare we pitched a tent, the onley one we had, and made him as

comfortable as circumtances would permit. This gave us a lisson on the

charcter of the grissly Baare which we did not forget.

In 1831, Jedediah Smith was guiding a wagon train to Sante Fe. The train took the

shorter Cimmarron Cutoff notorious for its lack of water. With the caravan running short of

water, Smith volunteered to seek out a spring. Along the Cimmarron, Smith was killed by a Comanchee arrow.

His body was never recovered. In his last letter to

Robert Cambell's brother Hugh, Smith expressed the hope of seeing his protégé but one more time,

"Oh is it possible I Shall never again See him in the Land of the living?"

"The Bar Tore Carver to Pieces," Frederic Remington, 1888

Hugh Glass survived a mauling by a grizzly, was left for dead by his

compatriots, and crawled with a broken leg, on two elbows, and one knee over one hundred miles. His life was

probably saved by another grizzly and by maggots in his wounds. On the journey, Glass passed out and awakened to

find the grizzly licking the maggots out of Glass's open wounds. There is evidence both scientifically and anecdotally

that saliva contains antiseptic aspects.

Some animal saliva may contain lysozyme, an enzyme that destroys harmful bacteria.

The licking may provides direct stimulation of the tissues and small blood vessels surrounding the wound site. Because of

risk of infection, it is not recommended that one allow animals to lick wounds.

The use of maggots to debride wounds has been traced back to the

Napoleonic Wars. In this country, the first intentional use of maggots for such purposes was apparently by a Confederate surgeon, J. F. Zacharias,

at Danville, Virginia to aid in the treatment of gangrene. See, Baer, William S.,

"The Treatment of Chronic Osteomylitis with the Maggot (Larva of the Blow Fly),"

Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 1931. In spite of, or maybe because of, the unorthodox treatment of his wounds by the

maggots and the bear, Glass fully recovered and returned to trapping. Along with

two companions, he was killed by Indians in 1833.

John Hoback, after whom Hoback Basin, Hoback River, Hoback Peak, and numerous other places in the West are named,

was killed along with the Reed wintering brigade by Indians in 1813.

During the War of 1812, Astoria was surrendered to the

British. One of the former members of the company at Astoria, Gabriel Franchère, commenced his epic journey by canoe and

foot across the continent to Montreal. In his 1820 account of his adventures,

Relation d'un voyage a la Cote du NordOuest de l'Amerique septentrionale darts les anndes 1810'14 (1854 translation by

Jedediah Vincent Huntington), Franchère reported the death of Hoback (spelled "Hubbough"):

On the 17th, the fatique I had experienced the day before, on horseback,

obliged me to re-embark in my canoe. About eight o'clock, we passed a

little river flowing from the N.W. We perceived, soon after, three canoes, the persons in

which were struggling with their paddles to overtake us. As we were still pursuing our

way, we heard a child's voice cry out in French -- "arrétez donc, arrétez donc" -- (stop! stop!).

We put ashore, and the canoes having joined us, we perceived in one of them the wife

and children of a man named Pierre Dorion, a hunter, who had been sent

on with a party of eight, under the command of Mr. J. Reed, anomg the Snakes, to join there

the hunters left by Messers. Hunt and Crooks, near Fort Henry, and to secure horses

and provisions for our journey. This woman informed us, to our no small dismay, of the

tragical fate of all those who composed that party. She told us that in the month

of January, the hunters being dispersed here and there, setting their traps for the beaver,

Jacob Regner, Gilles Leclerc, and Pierre Dorion, her husband, had been

attacked by the natives. Leclerc, having been mortally wounded, reached her

tent or hut, where he expired in a few minutes, after having announced to her

that her husband had been killed. She immediately took two horses that were near

the lodge, mounted her two boys upon them, and fled in all haste to the wintering

house of Mr. Reed, which was about five days' march from the spot where her

husband fell. Her horror and disappointment were extreme, when she found the house -- a

log cabin -- deserted and upon drawing nearer, was soon convinced, by the

traces of blood, that Mr. Reed also had been murdered. No time was to be

lost in lamentations, and she had immediately fled toward the mountains south of the

Walawalla, where, being impeded by the depth of the snow, she was forced

to winter, having killed both the horses to subsist herself and her children. But

at last, finding herself out of provisions, and the snow beginning to

melt, whe had crossed the mountains with her boys, hoping to find some more humane Indians,

who would let her live among them till the boats from the fort below should be

ascending the river in the spring, and so reached the banks of the

Columbia, by the Wallawalla. Here, indeed, the natives had received her with much

hospitality, and it was the Indians of the wallawalla who brought her to

us. We made them some presents to repay their care and pains, and they

returned well satisfied.

The persons who lost their lives in this unfortunate wintering party,

were Mr. John Reed, (clerk), Jacob Rener, John Hubbough, Pierre Dorion (hunters),

Gilles Leclerc, François Landry, J. B. Turcotte, André la Chapelle and

Pierre De Launay, (voyageurs).

Franchère notes that Turcotte died of "King's Evil" and that DeLaunay left Reed in the

autumn and was never heard from again. [Writer's notes: Alexander Ross's 1849 account,

Adventures of the First Settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River

: Being a Narrative of the Expedition Fitted Out by John Jacob Astor,

to Establish the Pacific Fur Company: With an Account of Some Indian Tribes

on of the Coast of the Pacific quotes Marie Dorion as indicating that

LeClerc died on the trip back to Reed's house. Irving's account also has LeClerc dieing on the

trip back. Marie Dorion died in 1850 near Salem, Oregon. Pierre Dorion was the

interpreter for the Hunt party and left St. Charles one step ahead of a

warrant sworn out by Manuel de Lisa for an unpaid debt. "King's Evil," a tubercular swelling of the lymph

nodes of the neck, so called because it could allegedly be cured by the touching of the

swelling by the royal hand.]

James Pierson Beckwourth.

Jim Beckwourth (1798-1866), who had participated in Ashley's expeditions was one of the few

mountain men to lead a full life. He acted as a scout in the Second Seminole War in Florida, went to

California where he rustled horses from Spanish-owned ranches, ran a store in Denver and in his

60's acted as a guide for the army including at the Battle of Sand Creek. In 1866, he acted as

a scout for Col. Henry B. Carrington's expeditions into northern Wyoming. Col. Carrington in his

report of November 14, 1866, noted Beckwourth's passing:

Only valuable information since last week's mail is that Crows in large numbers have camped near Fort C.F. Smith, and are friendly.

Guide Beckwith [sic] died while in their village.

William Guerrier blew himself to Kingdon Come during the winter of 1857-58 when one of his employees left a

keg of black powder on the front of a wagon with the lid off. Guerier, sometimes referred to in government

records as "Bill Garey", in stepping on the the tongue of the wagon accidently allowed some embers from his pipe to fall into the

open keg. Guerrier was noted as a proficient interpreter for the Cheyenne and ran the first cattle ranch in Wyoming near

Register Cliff near present day Guernsey. Guerrier, son-in-law of Gray Thunder, was the father of Edmond Guerrier, a survivor of

the Battle of Sand Creek. Edmond testified before Congress as to the slaughter. Edmond, college educated, followed in

his father's footsteps and served as an interpreter for the government. George Armstrong Custer in his

1874 My Life on the Plains, noted Guerrier's services in an 1867 meeting between General Hancock and

Roman Nose. Custer described entering a hastily deserted Cheyenne Lodge:

To complete the picture of an Indian lodge, over the fire hung a

camp-kettle, in which, by means of the dim light of the fire, we could see

what had been intended for the supper of the late occupants of the lodge.

The doctor, ever on the alert to discover additional items of knowledge,

whether pertaining to history or science, snuffed the savory odors which

arose from the dark recesses of the mysterious kettle. Casting about the

lodge for some instrument to aid him in his pursuit of knowledge, he found

a horn spoon, with which he began his investigation of the contents,

finally succeeding in getting possession of a fragment which might have

been the half of a duck or rabbit, judging merely from its size. "Ah!"

said the doctor, in his most complacent manner, "here is the opportunity I

have long been waiting for. I have often desired to test and taste of the

Indian mode of cooking. What do you suppose this is?" holding up the

dripping morsel. Unable to obtain the desired information, the Doctor,

whose naturally good appetite had been sensibly sharpened by his recent

exercise a la quadrupede set to with a will and ate heartily of the

mysterious contents of the kettle. "What can this be?" again inquired the

doctor. He was only satisfied on one point, that it was delicious-a dish

fit for a king.

Just then Guerrier, the half-breed, entered the lodge. He could

solve the mystery, having spent years among the Indians. To him the doctor

appealed for information. Fishing out a huge piece, and attacking it with

the voracity of a hungry wolf, he was not long in determining what the

doctor had supped so heartily upon. His first words settled the mystery:

"Why, this is dog." I will not attempt to repeat the few but emphatic words

uttered by the heartily disgusted member of the medical fraternity as he

rushed from the lodge.

A description of the interior of a tipi has been provided to us by

the Earl of Dunraven. He wrote that each tipe was shared by seveal families, their space

divided by a wicker-work wall, all spaces, however, opening to the common fire. Just as it is

bad form in a modern fraternal lodge, to cross between the station of the

presiding officer and the alter, in the tipi, Dunraven observed, the "fire is

common property, and has a certain amount of reverence paid to it. It is considered

very bad manners, for instance, to step between the fire and the place where the head

man sits."

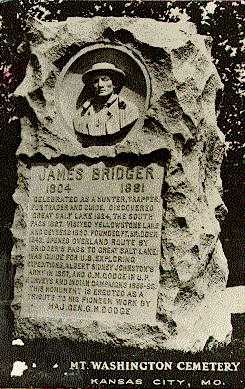

Bridger Grave, Mount Washington Cemetery, Kansas City

Although Bridger could not read or write he loved to be read

to, even to the extent that at one point he employed an

individual to read to him. He was particularly fond of Shakespeare and managed to memorize a large number of

passages which he would recite. Two explainations have been given for Bridger's love

of Shakespear. One is that Sir St. George Gore introduced Bridger to the bard. Another was given by

Eugene F. Ware (1841-1911) in his 1911 book, The Indian War of 1864:

The largest building in camp[See Ft. Laramie]

was called Bedlam. It was the two-story large hospital building

fronting on the parade-ground, and the upper part of it was used

for theatricals at times. There were always some soldiers who were

good at private theatricals, and occasionally there was one who had

been an actor. So, during the long and tiresome winter evenings there

were theatrical entertainments frequently. They were generally of some

light, witty, flashy kind, with an occasional heavy piece from Shakespeare.

Bridger had seen a couple of Shakespeare's pieces well played at the post,

and concluded he would like to have somebody read Shakespeare to him. So,

he had the sutler, Mr. Ward, send and get him a copy of Shakespeare, and

Bridger got a man, a soldier, to start reading it to him. One evening while

sitting in front of the adobe fireplace reading Shakespeare the soldier

got to reading in the play where the eyes of the two boy princes were put

out. After it had been read Bridger says, "Did he do that?" and when the

reader said, "Yes," Bridger pulled the book from him and said, "By thunder,

that is what I think of him," and threw the book into the fire, blazing

in the fireplace, and that was all of Shakespeare he ever wanted to hear.

In his later years Bridger became almost blind and

would ride around his farm in Missouri on a tame horse accompanied by his dog. When

Bridger would, due to his blindness, sometimes become lost. The dog would then, like Rin Tin Tin, run

back to the house to get someone to lead the great guide home. Bridger,

unlike many of his compatriots, died a natural death at his farm in Kansas City July 17, 1881, age 77.

In 1904, his remains were reinterred at Mount Washington Cemetery, Kansas City, with a monument erected

by General Dodge "as a tribute to his frontier work."

But the end of the mountain man era did not end trapping in Wyoming.

As discussed on a later pages, fur trapping was replaced by the buffalo hunters. And after the demise

of the bison, trappers, known as "wolfers," would be employed by ranchmen to eliminate wolves who would attack

calves and sheep. Ultimately, the great fur companies became

suppliers to the government, providing goods and transportation for the annual Indian annuity. Both Sublette and Campbell and the

American Fur Company engaged in steam navigation on the Mississippi and the

Missouri. Robert Campbell was a shareholder in two railway companies. Nevertheless in 1865, Pierre Chouteau and Company, then the

owner of the last

remnant of the American Fur Company, sold its operations in the upper

Missouri to the newly created Northwestern Fur Company.

Chouteau and Company traced its beginnings to the

very founding of St. Louis. Jean Pierre Chouteau was the son of the founder of

St. Louis, Pierre Laclede. His son, Pierre Chouteau, Jr., carried on the family fur business until Pierre Sr.'s death in

1865. William Sublette died in 1845 on a buying trip east for the next year's season,

but Robert Campbell continued the business, ultimately closing the mercantile business in 1871 and continuing on in real estate, railroads and

the hotel business. Campbell died in 1879 leaving an estate of $2,000,000. Three years later in 1881, Jim Bridger died in

Kansas City in relative poverty. Today, north of the border, only the Hudson's Bay Company remains. Thus ended the era of the mountain man in the

Rocky Mountain West.

Next page: Fort Bridger.

|