|

Trou a' Pierre, Pierre's Hole, Rendezvous

The system of rendezvous was established by William Henry Ashley and William Henry with the

Rendezvous of 1825 held near the confluence of Henry's Fork and Burnt Fork at present-day

Burntfork, Wyoming.

Site of the Rendezvous of 1825, Burntfork, Wyoming. Photo by Geoff Dobson

Site of the Rendezvous of 1825, Burntfork, Wyoming. Photo by Geoff Dobson

The Rendezvous is believed to have taken place in the area behond the first line of trees. Beyong is Burnt Fork. Along the base

of the bluffs is Henry's Fork. The advantage of a rendezvous was that it eliminated the high cost of constructing, manning and maintaining a

line of forts in the upper Missouri. The forts also proved inefficient in that as an area became trapped out,

the forts would no longer be in easy distance for the trappers. The advent of the

rendevous system also eliminated a major expense for the fur companies of salaries for employees known as

"engagés. Trappers were of two types,

engagés and freemen. The engagés could be either mere employees of the company or trappers contractually bound

to sell to the company as a result of the company advancing supplies at inflated prices.

Free trappers outfitted themselves and

could sell whereever they chose and keep the profits for themselves. The trappers who contracted to sell

their furs to the Company received less than freemen. Ashley paid the former $3.00 a pound for the

skins and paid $5.00 to free trappers.

Ashley estimated that some 120 men attended the first rendezvous including 25 deserters from the

Hudson's Bay Company, some 13 to 30 from Etienne Provst, 7 from Jedediah Smith's company, 25 to 30 from John H.

Weber's company and 25 from Ashley men. James Beckwourth, some 30 years later, recalled that there were some 800 in

attendance of which about half were women and children. He also recalled that the "whiskey went as freely as

water, even at the exorbitant price he sold it for." Ashley's inventory did not reflect liquor, a deficiency made up at subsequent

rendezvous. Ashley's prices do seem somewhat high: coffee and sugar $1.50 a pound, tobacco $3.00, powder $2.00, scarlet cloth $6.00 a yard. Blue cloth was

cheaper at $5.00 a yard. But then, it must be remembered the difficulty of getting the goods to the

site. Ashley purchased some 9,000 pounds of peltries at the rendezvous. In St. Louis these would bring almost

$50,000.00. It took his party from July until October to get the furs back going by way of

the Bighorn and Yellowstone Rivers.

Site of Green River Rendezvous of 1833, near Pindedale, photo by

Geoff Dobson

At the 1833 Rendezvous, a rabid wolf invaded the rendezvous grounds biting twelve of the trappers.

Four died the horrible and agonizing death of hydrophobia, one foaming at the mouth and barking in the

pain. On the return trip along the Bighorn River, one of the men went berserk and dashed into the

woods naked, never to be seen again. Thus, death was not an unnatural or appalling occurance. Such incidents, however,

did not slow down the festivities generated in part by the ready availability of

alcohol which sold for $5.00 a pint. At age 19, Joseph Meek attended his

first rendezvous near present day Lander. Years later, Meek described to

Frances Fuller Victor his distress in witnessing four

seasoned trappers playing a game of cards using the dead body of a compatriot as

the playing surface. Warren Angus Ferris, in the employ of the American Fur Company also

observed the cheapness of life:

A man in the employ of Smith, Sublette and Jackson,

was engaged with a detached party, in constructing one of those subterranean

vaults for the reception of furs, already described.

The cache was nearly completed, when a large quantity of earth fell in upon

the poor fellow, and completely buried him alive. His companions

believed him to have been instantly killed, knew him to be well buried, and the cache destroyed, and therefore left him

Unknelled, uncoffined, ne'er to rise,

Till Gabriel's trumpet shakes the skies,

and accomplished their object elsewhere. It was a heartless, cruel

procedure, but serves to show how lightly human life is held in these

distant wilds.

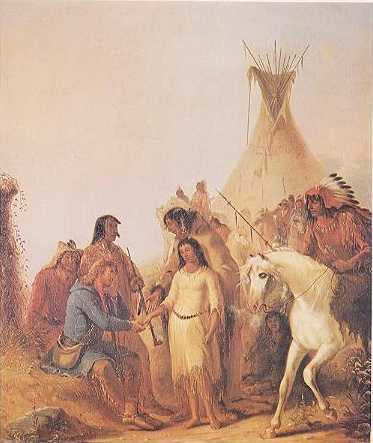

The Trapper's Bride, Alfred Jacob Miller, 1837

Miller indicated that the scene to the left was that of a trapper by the name of Francois who

purchased a bride from her father for $600.00 in trade goods. Since the

goods were brought by wagon from St. Louis, they were necessarily high. A rifle

went for $100.00, horse blankets for $50.00, and flannel for $20.00 a yard.

For discussion of Miller, see Fort Laramie.

Organization for the caravans to the west was difficult. Trade goods had to be acquired. In some instances, companies such

as the Rocky Mountain Fur Company would acquire the stock in trade from suppliers in St. Louis such as

William Henry Ashley. Profits were greater, however, if the goods were acquired directly from

manufacturers or dealers in the east. That meant a trip from St. Louis to Philadelphia or New York to purchase the goods,

transportation of the goods to Pittsburgh and then down the Ohio by keelboat to the

Mississippi, and then up the Mississippi to St. Louis. From St. Louis, the goods were shipped in

the lumbering caravans westward to Wyoming. The American Fur Company which dominated the

upper Missouri would ship its goods up the Missouri by keelboat and in later years by steam packet to Fort Pierre and then

overland to the rendezvous.

The keelboats were from 40 to 75 feet long and 15 to 20 feet wide and were shaped like a pirogue or canoe. Frederick Chouteau who

had a trading post near present day Topeka, described keelboats used by he and and brothers

Cyprian Chouteau and Francis G. Chouteau:

"The keel boat which my brothers had in 1828, I think, was the first which

navigated the Kansas river. After I came the keel boat was used altogether

on the Kaw river. We would take a load of goods up in August and keep it

there until the following spring, when we would bring it down loaded with

peltries. At the mouth of the Kaw we shipped on steamboat to St. Louis.

The keel-boats were made in St. Louis. They were rib-made boats, shaped

like the hull of a steamboat and decked over. They were about 8 or 10 feet

across the deck and 5 or 6 feet below deck. They were rigged with one mast

and had a rudder, though we generally took the rudder off and used a long

oar for steering. There were four row locks on each side. Going up the Kaw

river we pulled all the way; about 15 miles a day. Going down it sometimes

took a good many days, as it did going up, on account of the low water. I

have taken a month to go down from my trading house at American Chief

(or Mission) creek, many times lightening the boat with skiffs; other times

going down in a day. I never went with the boat above my trading house at

the American Chief village. No other traders except myself and brothers

ran keel boats on the Kaw. We pulled up sometimes by the willows which

lined the banks of the river." Kansas, A Cylopedia of State History, Standard Pub. Co., Chicago, 1912.

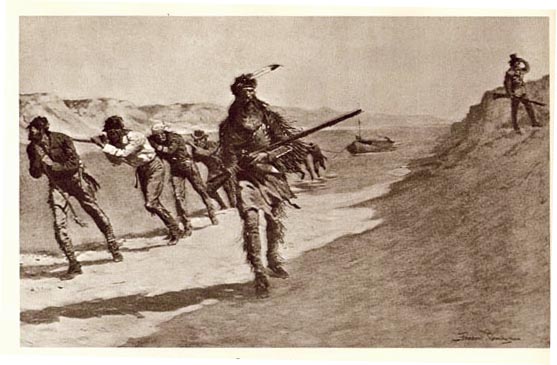

Up-River -- On the Yellowstone, Frederic Remington, Century Magazine, 1901

The above woodcut depicts a keelboat being dragged up the Yellowstone by early fur

traders. The men are using a cordelle, a rope fastened to the mast. The usual method of

ascending river was poling using poles eighteen to twenty feet long. The poles would have a crutch on one end into

which the men would set their shoulder. On the bottom end would be a knob or iron shoe to set against the

river bottom. The men would walk to the stern. When each pair of men reached the stern, they would run back to

the bow and begin the process over again. With a crew of twenty, at any given time 16 would be

walking toward the stern and four returning to the bow. A third method of ascending the river during highwater would be

"bushwwhacking;" that is, pulling on the bushes and willows along the shore.

The goods constituted a veritable department store: cloth, butcher and scalping knives, rifles, mackinaw blankets, vermillion, powder

horns, tools, bridles, Spanish saddles, sugar, ink, paper, quills, flints, calico, flannel, shirts, kettles,

traps, axes, branding irons, wool socks, combs, beads, rope, four, coffee, and, of course,

alcohol. In 1830, as an example, William Sublette carried to the Rendezvous on the Wind River some $30,000 in goods in

ten ox-drawn wagons along with 12 beef cattle and a milk cow.

A license had to be obtained. The alcohol could not, of course, be legally sold to Indians, and, indeed,

importation into Indian country was extremely limited. The process was, however, evaded. Thus, William Sublette obtained

a license for 450 gallons of whiskey on the basis that it was for his "boatmen." In 1832, the American Fur Company was licensed for

1400 gallons of alcohol for "medicinal purposes." Ultimately, the American Fur Company solved the

ban by constructing its own distillery at Fort Union from which it was able to

amply supply the market. The American Fur Company also resorted to old-fashioned smuggling. Hirem Martin Chittenden relates in his

1902 The American Fur Trade in the Far West an 1843 incident in which the

naturalist John J. Audubon assisted the Company in getting the offending booze past a government inspector, Audubon had a government license

for a personal stock of liquor. He used a substantial portion of the private stock to get a young

captain well lubricated so that he would miss the liquor hidden in the hold of the Company's vessel.

Audubon with three assistants was visiting the upper Missouri preparatory to the publication of

his The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America. The following year, the

Company hid the liquor in barrels of flour ostensibly consigned to the Company's agent Peter Sarpy. To get the

liquor past the inspector, a Methodist minister, the barrels were dutifully unloaded at Sarpy's dock. For some strange

reason, however, after the flour was unloaded, the steamboad did not proceed upstream but remained tied up at

dockside. Curiously, all through the night the captain maintained a full head of steam. In the dark of the night,

the "flour" was reloaded on board. At 3:00 a.m., the reverend inspector received word that something suspicious was afoot at dockside. As he

arrived, the steam packet was making upstream toward Fort Union at full ahead. Others imported the whiskey from Taos.

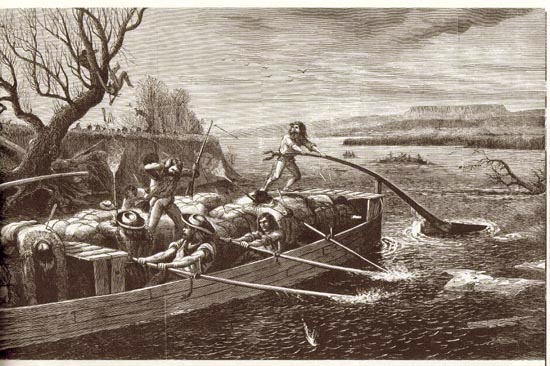

Fur Boat on Missouri, woodcut, Harper's Weekly, 1868, from drawing by W. M. Cary

Once the goods were traded for furs at the Rendezvous, the companies had the difficulty of transporting the pelts back to

St. Louis. In some instances, such as depicted above, the livestock would be driven overland back to

Missouri, while the furs would be transported via Bad Pass to the head of navigation on the Bighorn River near its

confluence with the Yellowstone. There, keelboats used to transport goods to

trading posts on the upper Missouri, or homemade boats would be used to

transport the pelts back to St. Louis. The homemade boats would be of

two types, "mackinaws" or "bullboats." The mackinaw was a wooden boat depicted above. The boat would be divided into four sections by two bulkheads and would be propelled by

oarsmen, The rudder at the rear was steered by a man known as the "patron."

The bullboat was constructed of the hide of buffalo bulls, stretched over a willow frame and made water tight with either pitch or

buffalo tallow and ashes. The bullboat was extremely light and, thus, had a very shallow draft suitable for

navigation in which the river's depth would be measured in inches. Thus, in one instance, in 1835, Robert Campbell was

able to transport hides down the Platte in bullboats when his mackinaw had too great a

draft. The Nineteenth Century humorist Artemus Ward noted of the shallowness of the Platte,

"the Platte would be a good river if set on edge." The bullboats had the advantage that

they could be manned by two men, but had to be taken ashore each night, unloaded, and recaulked.

William de la Montagne Cary (1840-1922) was an artist for a number of magazines, including Harper's and

Leslie's. He learned artwork at an early age from his father and was later apprenticed to an engraver.

In 1861, he headed west by wagon train. Near Fort Benton he was captured by Indians but was

released at the behest of an official with a fur company. Near Ft. Union he took passage on the

steamboat Chippewa, which unfortunately exploded. Cary survived but he lost approximately 80 sketches.

He returned west in 1867 and 1874. Most of his paintings and illustrations were based on a combination of

sketches and memory.

In contrast to the American keelboats, mackinaws and bullboats, the Canadians used Canots du Maitre or Montreal

canoes. The Canadian canoes were 35 to 40 feet long and required 10 or 14 men. The canots could, however, hold some 10,000 pounds.

At the end of Lake Superior, the cargoes would be reloaded into smaller birch bark canoes each capable of

holding 3,000 pounds including a crew of six.

Next page: Rendezvous continued, Jim Bridger, Joseph Reddeford Walker, Moses "Black" Harris.

|