|

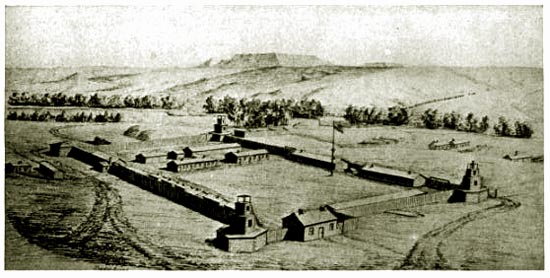

Fort Reno, Dakota Territory, 1867. A bird's eye view from the

southwest. Drawing by Anton Schonborn.

In 1864, the Bozeman trail was opened from Ft. Laramie up to gold fields of Montana. With increased

Indian depredations following Sand Creek, the trail was soon closed to civilian traffic. The military continued with expeditions

into the area. On August 31, 1865, a road building expedition under Col. J. A. Sawyer was attacked at the Tongue River Crossing of the

Bozeman Trail near present day Dayton, Wyoming. It is believed that the attack was in retribution for an

attack on an Araphaho Village two days earlier by Gen. Patrick E. Connor. In the attack at present day Ranchester

the Indians had an estimated 60 killed and lost 250 lodges and 1,100 horses.

Site of the Seige of the Sawyer Road Building Expedition. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

Col. Sawyer circled his wagons in the field between the viewer and the Tongue River marked by the line of

trees. For thirteen days, the 82 wagons remained under attack until finally relieved by a unit from

Gen. Connor's command. The road building effort by Col. Sawyer was abandoned.

In order to protect the

trail, Forts Reno, Kearny, and Smith were constructed and the trail reopened.

Few images of those forts remain through the mists of times.

It is believed that the drawing of Ft. Reno is one of only two images of the fort to survive.

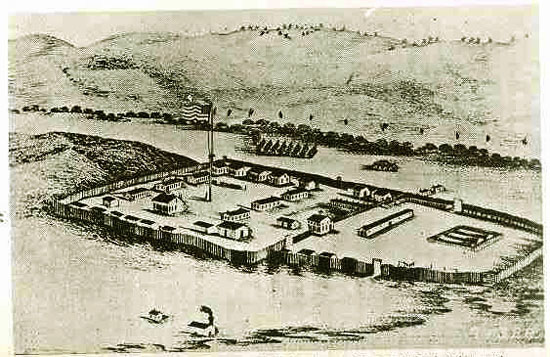

Fort Phil Kearny looking to the northwest. Sketch by Antonio Nicolai.

In the northwest corner of the fort is the hospital and bakery. The three building immediately below the bakery on the

west (left) side of the parade ground are barracks as are the three building on the east side. The large

building on the south side of the parade grounds is the commanding officer's quarters. The large trapazoidal area on the

east (right) side of the fort is the quartermaster's corral. The flagpole is only a little exaggerated; it was 124 feet high. The flag

measured 20 ft. by 36 ft. The building outside the

fort on the north side is a civilian eatery. Troops going to the pineries on wood cutting details, would follow the ridge

immediately to the west of the fort. By following the ridge, ambushes by Indians could be avoided. Antonio Nicolai was

a bugler. Through the use of various bugle calls, a commander in the field could relay

signals or orders to the men. Thus, the bugler also acted as an aide.

Fort Phil Kearny looking to the northwest. Sketch possibly by

Ambrose Bierce.

In 1866, the Inspector General of the Department of the Platte, Captain (Bvt. Brig. Gen.) William

B. Hazen, began an inspection tour of the western forts. The tour included Forts Reno, Kearny, and Smith, as well as forts along

the Yellowstone and Fort Benton. Accompanying him was a civilian cartographer Ambrose

Bierce. Bierce (1842-191?), later to achieve fame as a writer and as a result of his unexplained disappearance in

1913, had served under Hazen in the Civil War as a cartographer. Following his mustering out, he briefly was employed by the

government in reconstruction efforts in the South. He applied for a commission as a captain in the

military and while the application was reviewed served as a civilian cartographer for Hazen. In 1877, Bierce was

offered a commission as a 2nd lieutenant. The proffered commission was rejected. Bierce took employment with the

federal mint in San Francisco and commenced his newspaper and writing career. For a short period, 1879-80, he was

employed in mining in the Black Hills. For more on Bierce see Deadwood Stage.

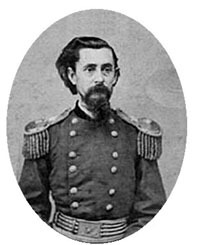

Henry Beebee Carrington

Henry Beebee Carrington

Construction of Ft. Phil Kearny started on June 15, 1866, under the command of

Col. Henry Carrington (1824-1912). In October, the Fort was

formally dedicated. By December, the barracks, the commissary and quartermaster's buildings had

been completed, and temporary officers quarters had been constructed by members of the

regimental band. To aid the construction, the Army brought in two

steam-powered saw mills. Almost immediately, Indian attacks commenced. On June 30, Indians drove off 278 mules and

seven horses belonging to Ft. Reno's sutler, A. C. Leighton. On July 17, seventy-five government mules were lost. On the

same day an Indian trader, French Pete, and seven of his men were killed. On the

20th, a civilian train was attacked. Four days later an Army train was attacked at the Clear Fork of

Powder River, and so it went, with almost weekly attacks on civilian and government trains. J. B. Weston observed that the

road, "was strewn, all along the line, with new made graves, and other fresh and bloody tokens of Indian hostilities."

The military position became more and more

untenable. Indeed, the tokens of the Indian hostilities remained visible for years. S. H. Woods, the second boss of one cattle drive along

Powder River in 1881, observed along the trail between the North Platte and Powder River:

For about the distance of half a mile the trail on both sides wer strewn with oxen bones, irons and pieces of wagons where

they had been burned, but did not see any human bones because I didn't take time to make a

close examination."

Nevertheless, some trains got through. One supply train crossing the hot parched plains bearing medical supplies has provided one of

Wyoming's enduring unsolved mysteries.

Among the medical supplies were 258 bottles of beer intended to relieve those suffering from the

ministrations of the post hospital. When the wagons arrived at Fort

Phil Kearny, there were only 53 bottles. Although subject to speculation, no definitive

explanation has ever been offered for the disappearance of the remaining beer.

One of the routine tasks necessary

for an isolated fort was the cutting and storing of wood for winter. As the

winter of 1866 approached, attacks upon wood cutting details became more and more

frequent and the fort was, in essence, under a state of seige. The wood lots, known as "pineries," were located some miles

distant along the base of the Big Horns. It became necessary for

the wood cutting parties to have an escort and to follow ridges from the fort rather than

travel along the bottom lands. By following the ridges, ambushes could be avoided.

Red Cloud was amassing large forces hidden from view of the Fort. On December 21, a Friday, the wood train departed

the fort with an escort. Within an hour a signal was received that the

train was under attack. A column, under Capt. Fetterman with Frederck Brown

in second command, was sent forth by Col. Carrington to relieve the train. Carrington, as a result of

an attack and decoy two weeks before, gave direct orders that Fetterman under no cirumstances was

to go beyond the Lodge Trail Ridge. Carrington later wrote in his report of January 3, 1867:

Hence my instructions to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman, viz: - "Support the wood train, relieve it and report to me. Do not engage or pursue Indians at its expense. Under no circumstances pursue over the ridge viz; Lodge Trail Ridge, as per map in your possession."

To Lieutenant Grummond, I gave orders to report to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman, implicitly obey orders and not leave him.

Before the command left, I instructed Lieutenant A.H. Wands, Regimental Quarter Master, and Acting Adjutant, to repeat these orders. He did so. Fearing still that the spirit of ambition might override prudence, (as my refusal to permit sixty mounted men and forty citizens to go for several days down Tongue river valley after villages, had been unfavorably regarded to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman and Captain Brown,) I crossed the parade and from a sentry platform, halted the cavalry and again repeated my precise orders.

Indeed, Fetteerman was unfavorably disposed to his commanding officer. In a letter cited by Shannon Smith Calitri in support of her apparent position

that it was Carrington who was incompetent, Fetterman wrote, "We are afflicted with an incompetent commanding officer * * *." Calitri,

Shannon Smith,

"Give Me Eighty Men': Shattering the Myth of the Fetterman Massacre,"

Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Autumn 2004. Calitri seeming takes the

position that Fetterman was

"an excellent officer, a chivalrous gentleman, and a compassionate superior who commanded devout loyalty from his men.

His substantial military record shows him to have been a man with outstanding

leadership skills both in battle and in administration and an officer who was thoroughly

indoctrinated in the military code of conduct."

Lt. Fetterman had arrived at the fort in November and had bragged that with 80 men he could go through the

entire Sioux Nation. Not withstanding Carrington's orders, at the train a small group of Indians were observed and pursuit was

given over the ridge and through the small draw on the right in the next photo.

Lodge Trail Ridge, looking south from Massacre Hill. Photo by Geoff Dobson

Lt. Fetterman proceeded onto the hill in the next photo where his force was surrounded by an overwhelming force of Indians.

Massacre Hill. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

At the fort reports of sounds of the gun fire were received.

An additional column was dispatched under the command of Capt. Tenador Ten Eyck. By the time

Ten Eynk arrived all eighty men in Fetterman's units had been slaughtered. In the face of Capt.

Ten Eynk's advance, the Indians retired. Capt. Ten Eynk testified as to the condition of the dead:

In their appearance they were all stripped stark naked, scalped, shot full of arrows and horribly

mutilated otherwise, some with their skulls mashed in, throats cut of others,

thighs ripped open, apparently with knives. Some with their ears cut off,

some with their bowels hanging out, from being cut through the abdomen,

and a few with their bodies charred from burning, and some with their noses

cut off. I was able to recognize several whom I was most intimately

acquainted with, and among them Capt. F.H. Brown.

From the positions of bodies it was apparent that Brown and Fetterman, rather than fall into

the mercies of the Sioux, had saved their last bullets for themselves.

John "Portugee" Phillips John "Portugee" Phillips

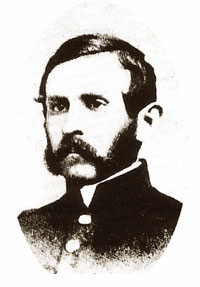

Capt. William J. Fetterman

Capt. William J. Fetterman

Following the Fetterman Massacre, there was a fear that the fort, itself, might be taken by

the Indians. Woman and children were confined to the powder magazine. Instructions were given that

if the fort were taken, the magazine would be blown up to protect the woman and children from the

mercies of the Indians. Additionally, John "Portugee" Phillips (1832-1883),

a civilian, was dispatched 190 miles to Horseshoe Station, near present day Glendo,

the site of the closest telegraph.

Perservering through blizzards, he arrived and managed to

send the message to Ft. Laramie and Army headquarters in Omaha before the Indians

burned the station. He then continued his journey through yet another blizzard and finally arrived in Ft. Laramie

on Christmas Eve. As he entered the confines of the fort his horse dropped dead. Phillips, himself,

was required to recouperate in the post hospital for two weeks. Later, Phillips operated a

road ranch south of Chugwater on the Deadwood Stage Road.

Because of delays in paper work related to his American citizenship, no Army recognition was

given of his feat. In 1899, the Wyoming Legislature posthumously awarded him

$5,000.00 which was presented to his widow. [Writer's note: Historians for

the National Park Service have been unable to find a contemporaneous report of

the death of Phillips' horse. This is not surprising, especially considering that

other documents relating to the incident have been lost, including Col. Wessels'

message to Col. Innes N. Palmer, commander at Ft. Laramie.

In light of the other problems with which the Army had to deal, it

is doubtful that the telegrah wires to Omaha would be burning up with the

details of the demise of the animal. Palmer, for his services in the Civil War, bore the rank of

Brevet Major General. Wessels, commander at Fort Reno, also had a Civil War rank of

Brig. General. Thus, as George Armstrong Custer is often referred to as "General," even though

his actual rank was Lt. Colonel, Wessels and Palmer are frequently referenced with their

brevet rank of general.]

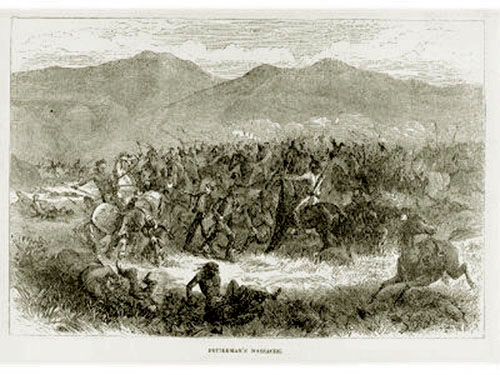

Fetterman Massacre

And the cause of the debacle? John B. Weston, after whom Weston County would later be named, was at

Ft. Phil Kearney at the time. He later testifed as to his opinion of blame:

1st On account of attempting to take possession of a country by an

inadequate military force, without having obtained consent of the Indians

who occupied it.

2nd The Indians in this country are very numerous, very wild, well armed,

mounted and appointed; and their constant and repeated successes, against

the weak and poorly appointed Government force in the country, has tended

to strengthen, encourage and embolden them; has enabled their Chiefs to

unite and consolidate the various tribes to the present very formidable

force, embracing, as I believe more than six thousand warriors.

Also the Indians naturally resist the opening up of a great National

highway to Virginia City, through a fine country abounding in game,

upon which they rely for their subsistence.

3rd The Indians have been cut off and driven back from every quarter,

and this Powder River country alone remains to them intact. It is the

last and perhaps the finest Indian country extant. The Indians are well

aware that the country besides posessing [sic] almost unlimited resources,

such as they require for their sustenance and support, is also a country

rich in agricultural and mineral resources. They know that while coal and

iron are abundant, that the more precious minerals exist in paying

quantities, in some parts of the country; and they have always been

jealous of the Whites getting a foothold in the country on that account.

They are no fools. They see the results in other mining territories; and

know perfectly well that a knowledge of these mineral resources would

only result in an absorption of the country by the Whites.

Lastly-Stupid and criminal management of our Indian Affairs by the U.S.

Government. The Government, as represented by the Officials of the Indian

Bureau, has never seemed to have any clear understanding of the Indian

problem. Instead of preparing the way for the inevitable advance of

civilization over this country, they have, as far as my observation has

gone, been absorbed in some scheme of personal [s]peculation. And when this

management has resulted in bringing on an Indian war, the War Department

has failed to appreciate its extent and magnitude; has sent a military

force to this country so small, inadequate, and insufficient in numbers,

arms and supplies, that instead of conquering a peace, it has aggravated

and augmented the troubles.

Of course, someone must be the scapegoat. Col. Carrington was elected. In January,

Col. Wessels arrived with orders relieving Carrington from command at Fort Kearny and transferring

him to Fort Caspar. The weather remained a bit nippy. For the women and children accompanying

Col. Carrington, the quartermaster fitted several wagons up like early versions of sheep wagons, closing in

one end and putting a door on the other. Inside the wagons the quartermaster placed a stove.

And like Elizabeth Custer some years later, it was up to Margaret Irvin Carrington (1831-1870) in her

1868 Ab-sa-ra-ka, Home of the Crows: Being the Experience of an Officer's Wife on the Plains

to attempt to salvage her husband's reputation. She described the scene as her

husband rode into disgrace:

The wheels creaked, the mules made their usual vocal sounds at the early

disturbance of their feed, and everybody shrunk into clothing as closely as

possible to evade the increasing cold."

At night it became quite nippy. The temperature dipped to forty below zero. Men had to be

whipped so they would not fall asleep and freeze to death. Not withstanding the stoves furnished by the

quartermaster, within the wagons for the woman and children the thermometer

"lingered about thirteen degrees below zero." When the party arrived at Fort

Reno, several men had to have frozen limbs amputated. They died anyway.

Music this page: "Lorena." Lorena was a popular song of the Civil War. It was so popular that some military commanders, particular in the

South, attempted to have it banned as depressing to morale. For lyrics see cattle trails.

Next page: The Wagon Box and Hay Field Fights, the Treaty of Ft. Laramie.

|