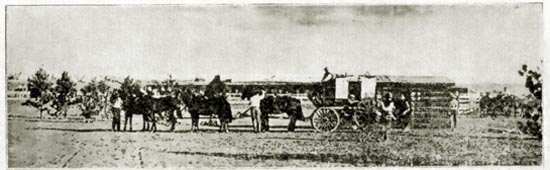

Deadwood Stage, Buffalo Bill Museum, Cody. Photo

by Geoff Dobson.

The line used both smaller coaches drawn by four

horses and larger

18-passenger coaches pulled by six horses. The

drivers often in arriving at their final destination

would make "a show of it", thundering into town with the red or yellow Concord

coaches "licky-cut", pulled by a matched team of six horses.

With the stages carrying gold, the danger from road agents was always present, indeed,

to such an extent that the line used a ironclad coach named the "Monitor" for

transporting gold. The coach, specially constructed in Cheyenne, was lined with iron plate with a

"treasure box" bolted to the floor on the inside. According to Scott Davis, one of the Company's

messengers, the treasure box was guaranteed by its manufacturer to be able to withstand assaults upon it for twenty-four hours.

At the 1914 Wyoming State Fair, he explained: "It was not supposed that a gang of robbers running around through the

mountains could get into the safe within the guaranteed time." As quoted in "The Story of the Cheyenne-Deadwood Treasure Coach Hold-up at

Cold Springs, Wyoming. September 29th, 1878," Proceedings and

Collections of the Wyoming State Historical Department, 1919-1920, p. 125.

The Monitor's "Treasure Box."

Regular passengers were not permitted and extra guards

known as "messengers" would be on board. Among those who were employed at various times as

messengers were D. Boone May, discussed below, and Wyatt Earp. The Monitor, itself, was held up by road agents on September 26, 1878,

at the Canyon Springs Station. The coach was driven by Gene Barnett with Galen "Gale"

Hill riding "shotgun" next to the driver. Inside were messengers Scott Davis and Eugene Smith and company

telegraph operator H. O. Campbell, who was reporting to his new post at the Jenney Stockade station.

When the coach pulled into the station, no one was to be seen. Normally as a coach nears a station, the

driver would blow for the horses. The station attendant, in this case, William Miner, would have

a fresh team out and ready. For more on blowing horses see Overland Stage.

Barnett and Hill alit from the box, with Barnett going to look for Miner and Hill chocking the

rear wheels of the coach. Shots rang out. Hill was wounded, Campbell killed and Davis lit out for the

woods. The road agents

had little difficulty in breaking open the supposedly impregnable safe used for

carrying the gold.

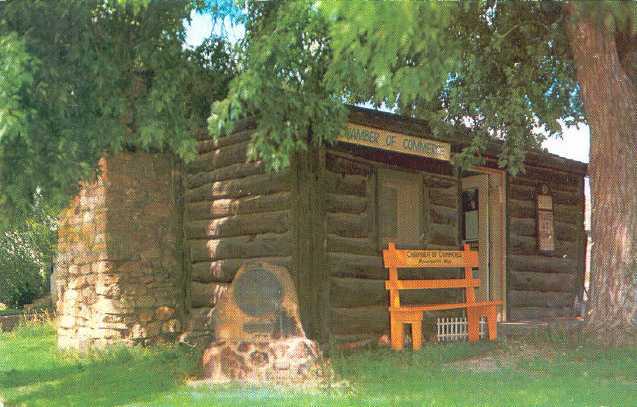

Modern view of Jenney Stockade stage station

Meanwhile at the Jenney Stockade station, three relief messengers, Boone May, Jesse Brown, and Bill Sample, awaited the arrival of the

coach. When it did not appear, the three rode north and eventually came across Davis riding south for help on a horse he

had borrowed at a neighboring ranch. The four then proceeded to the Canyon Springs Station where they

found the coach abandoned with the treasure box empty, Miner locked in the

granary, the relief team stolen, and other employees bound and gagged tied to

trees in the woods. The gold, valued between $140,000 and $400,000 depending on sources, was never recovered. Note:

Davis contended that much of it was recovered later.

Hill died several years later from complications from his wounds.

Canyon Springs Station

Later that year, William Mansfield and Archie McLaughlin attempted to sell stolen

bullion in Deadwood City. They were taken to Cheyenne for trial, but on the way the

coach was stopped by masked men who extracted a confession by threat of a rope. In Cheyenne,

trial was delayed and the prisoners were taken back to Deadwood City. On the way, masked

men again held up the stage near Cheyenne Crossing, removed the prisoners and hanged them leaving their

bodies to be removed by a passing troop of soldiers.

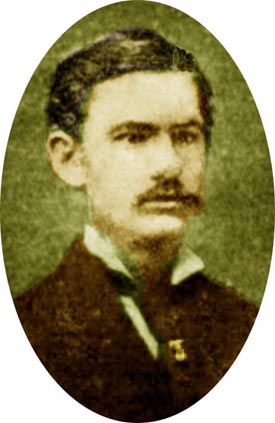

Galen Hill Galen Hill

Nor was that the only time prisoners were removed from the stage to insure that they met their

Maker. In October 1878, the rustler, Cornelius "Lame Johnny" Donahue, was being returned from Chadron to Rapid City

by James L. "Hawkbeak" Smith, more commonly referred to as "Whispering Smith." The nickname "Hawkbeak" was not one

to be used to Smith's face. The name came from the shape and size of his probiscus. Smith was

described by Edgar Beecher Bronson in his 1910 The Red-Blooded Heroes of the Frontier:

A type diametrically opposite to that of the debonair Boone May was

Captain Jim Smith, one of the best peaceofficers the frontier ever

knew. Of Captain Smith's early history nothing was known, except that

he had served with great credit as a captain of artillery in the Union

Army. He first appeared on the U. P. during construction days in the

late sixties. Serving in various capacities as railroad detective,

marshal, stock inspector, and the like, for eighteen years Captain

Smith wrote more red history with his pistol (barring May's work on the

Sioux) than any two men of his time.

The last I knew of him he had enough dead outlaws to his

credit--thirty-odd--to start, if not a respectable, at least, a

fair-sized graveyard. Captain Jim's mere look was almost enough to

still the heart-beat and paralyze the pistol hand of any but the

wildest of them all. His great burning black eyes, glowering deadly

menace from cavernous sockets of extraordinary depth, were set in a

colossal grim face; his straight, thin-lipped mouth never showed teeth;

his heavy, tight-curling black moustache and stiff black imperial

always had the appearance of holding the under lip closely glued to the

upper. In years of intimacy, I never once saw on his lips the faintest

hint of a smile. He had tremendous breadth of shoulders and depth of

chest; he was big-boned, lean-loined, quick and furtive of movement as

a panther. In short, Captain Jim was altogether the most

fearsome-looking man I ever saw, the very incarnation of a relentless,

inexorable, indomitable, avenging Nemesis.

Like most men lacking humor, Captain Jim was devoid of vices; like all

men lacking sentiment, he cultivated no intimacies. Throughout those

years loved nothing, animate or inanimate, but his guns--the full

length "45" that nestled in its breast scabbard next his heart, and the

short "45," sawed off two inches in front of the cylinder, that he

always carried in a deep side-pocket of his long sack coat. This was

often a much patched pocket, for Jim was a notable economist of time,

and usually fired from within the pocket. That he loved those guns I

know, for often have I seen him fondle them as tenderly as a mother her

first-born.

Boone May was the

messenger and Jesse Brian was the guard. Donahue, unlike most outlaws of the west, was college

educated (Girard College, Philadelphia) but got into trouble in Texas for rustling. He changed his name and moved to

the Black Hills. Unfortunately he was recognized. Thus, Donahue returned to his former profession.

At Buffalo Gap for some unexplained reason, May and Brian left the stage. Shortly thereafter two

unidentified masked men stopped the stage and removed Donahue. The stage then proceeded on.

Still in shackles, Donahue was hanged from an

elm tree near present-day Lame Johnny Creek, a tributary of the Cheyenne. The next day, some

bullwhackers found the body and gave it a burial. A small headboard was erected. In some sense there is

a pun in the wording of the grave marker. Donahue was noted for having a large mouth. Lame Johnny's

epitaph:

"Stranger pass gently o'er this sod,

If he opens his mouth, you're gone, by God."

For more on Whispering Smith see, The Wild Bunch.

Deadwood Stage crossing the Cheyenne, undated

An additional armored stage known as

"Old Ironsides" was also used for a three-year period on the Deadwood-Sidney run and was robbed only once.

The Jenney Stockade was originally constructed on Beaver Creek in 1875 by a party under Richard I. Dodge and

Professor Walter Jenney who were exploring the Black Hills. The stockade was on the site of

a corral constructed by G. K. Warren. In 1877 it became a stage station at one end of a

night run between it and the Hat Creek Station. Subsequently, the structure was moved to

Newcastle where it is now part of a museum.

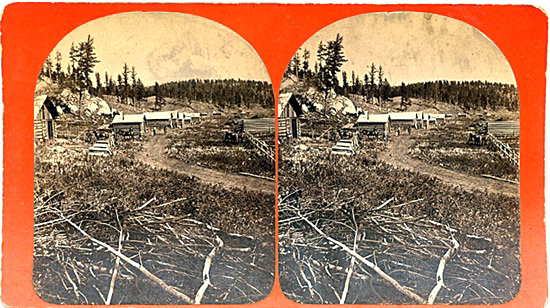

Hill City, Dakota Territory, approx. 1878. Stereograph by

Justus Fey.

Justus Fey was born in Hesse, in present day Germany. By 1878, he had established

a photography studeo in Deadwood City. He also worked as a machinist.

The Bass Gang, L. to R. Bass, Collins and (possibly) Murphy. See text below.

During one two-month period the Deadwood stage was held up four times by the Sam Bass Gang, consisting of

Bass, Joel Collins, Tom Nixon, Bill Heffridge and Jim Berry.

The first driver killed was Johnny Slaughter on March 25, 1877, driving a stage

bearing eleven passengers and $15,000. The stage was delayed by spring snow and

mud and a breakdown five miles north of Hill City. Two miles outside of

Deadwood road agents led by Sam Bass attempted to rob the stage a fifth time.

In the process

Slaughter was killed, the horses bolted, running off toward town only to be

stopped when the lead horses became entangled in the leads.

Slaughter's body was returned by special

coach to Cheyenne, where his hearse

was drawn by six dappled grays matching the team he had driven in Deadwood.

The gang fled to Nebraska where they robbed the Union Pacific train at Big Spring

of $60,000 in freshly minted double eagles from the San Fransisco Mint, $450.00

from the mail car safe and $1,300.00 from the passengers. Following the robbery

Collins and Heffridge were killed by a sheriff's posse near Buffalo Station, with

$25,000 being recovered.

Berry was captured at Mexico, Missouri and Nixon disappeared carrying, according

to Berry, $10,000, never to be seen again. Another alleged member of the Bass Gang,

Frank K. Towle, was killed later the same year while attempting to rob the stage.

One of the guards on the stage, Boone May, upon his return to Cheyenne discovered that there

was a price upon Towle's head. May then returned to the scene of the attempted

crime, found Towle's remains, cut off the head, and returned with his gory proof to Cheyenne

in order to collect the reward. Unfortunately, word had already gotten out about

Towle's demise and the reward had been cancelled. Thus, May's trip was for naught and

all he had for his efforts was a rather unusual souvenir. Ultimately, May disposed of

Towle's head by burying it outside of Cheyenne. It was dug up by prairie dogs who used it as

a toy.

Sixteen months after the killing of Slaughter, Bass was ambushed at Round Rock, Texas, by

Texas Rangers

to whom Bass was betrayed by Jim Murphy, a member of his gang. A compatriot,

Frank Jackson, escaped with an indeterminate amount of gold coin, which Bass had

being carrying in his saddlebags. Two days later on his 27th

birthday, July 27, 1878, Bass died from gunshot wounds

received in the ambush, his last words, "The world is bobbing around."

D. Boone May

It has been written of May, reputedly the "fastest gun

in the Dakotas," that "his corpses were invariably those of undesireable citizens, never

of the law abiding." In at least one instance a jury believed that the corpse was of an

undesireable, Curly Grimes, so called for his dark, shoulder length locks. May and William H. H. Llewellyn, a government agent had

taken Grimes, a suspected road agent into custody. Grimes' body was found frozen in

the snow near Hogan's Ranch. When tried for the murder of Grimes, the jury believed

Llewellyn and May's version that Grimes had attempted to escape and found the two "not guilty."

May ultimately, himself, became a fugitive from justice and disappeared, allegedly to South

America where, according Ambrose Bierce, he died of yellow fever.

Ambrose Bierce

Bierce, later to gain fame as an author and as a result of his unexplained disappearance, managed the

Black Hills Placer Mining Co., 1879-1880. The company organized in 1879 and capitalized at $10,000,000.00

constructed a twenty-mile long, $2,000,000 flume for its mining operation.

In his A Sole Survivor Bierce

wrote of May:

One night in the summer of 1880 I was driving in a light wagon through the

wildest part of the Black Hills in South Dakota. I had left Deadwood and was

well on my way to Rockerville with thirty thousand dollars on my person,

belonging to a mining company of which I was the general manager.

Naturally, I had taken the precaution to telegraph my secretary at

Rockerville to meet me at Rapid City, then a small town, on another route;

the telegram was intended to mislead the “gentlemen of the road” whom

I knew to be watching my movements, and who might possibly have a

confederate in the telegraph office. Beside me on the seat of the wagon sat

Boone May.

Permit me to explain the situation. Several months before, it had been the

custom to send a “treasure-coach” twice a week from Deadwood to Sidney,

Nebraska. Also, it had been the custom to have this coach captured and

plundered by “road agents.” So intolerable had this practice become—even

iron-clad coaches loopholed for rifles proving a vain device—that the mine

owners had adopted the more practicable plan of importing from California a

half-dozen of the most famous “shotgun messengers” of Wells, Fargo &

Co.—fearless and trusty fellows with an instinct for killing, a readiness

of resource that was an intuition, and a sense of direction that put

a shot where it would do the most good more accurately than the most

careful aim. Their feats of marksmanship were so incredible that seeing was

scarcely believing.

In a few weeks these chaps had put the road agents out of business and out

of life, for they attacked them wherever found. One sunny Sunday morning

two of them strolling down a street of Deadwood recognized five or six of

the rascals, ran back to their hotel for their rifles, and returning killed

them all!

Boone May was one of these avengers. When I employed him, as a messenger,

he was under indictment for murder. He had trailed a “road agent” across,

the Bad Lands for hundreds of miles, brought him back to within a few miles

of Deadwood and picketed him out for the night. The desperate man, tied as

he was, had attempted to escape, and May found it expedient to shoot and

bury him. The grave by the roadside is perhaps still pointed out to the

curious. May gave himself up, was formally charged with murder, released on

his own recognizance, and I had to give him leave of absence to go to court

and be acquitted. Some of the New York directors of my company having been

good enough to signify their disapproval of my action in employing “such a

man,” I could do no less than make some recognition of their dissent, and

thenceforth he was borne upon the pay-rolls as “Boone May, Murderer.” Now

let me get back to my story.

I knew the road fairly well, for I had previously traveled it by night, on

horseback, my pockets bulging with currency and my free hand holding a

cocked revolver the entire distance of fifty miles. To make the journey by

wagon with a companion was luxury. Still, the drizzle of rain was

uncomfortable. May sat hunched up beside me, a rubber poncho over his

shoulders and a Winchester rifle in its leathern case between his knees.

I thought him a trifle off his guard, but said nothing. The road, barely

visible, was rocky, the wagon rattled, and alongside ran a roaring stream.

Suddenly we heard through it all the clinking of a horse’s shoes directly

behind, and simultaneously the short, sharp words of authority: “Throw up

your hands!”

With an involuntary jerk at the reins I brought my team to its haunches

and reached for my revolver. Quite needless: with the quickest movement

that I had ever seen in anything but a cat—almost before the words were out

of the horseman’s mouth—May had thrown himself backward across the

back of the seat, face upward, and the muzzle of his rifle was within a

yard of the fellow’s breast! What further occurred among the three of us

there in the gloom of the forest has, I fancy, never been accurately

related.

Boone May is long dead of yellow fever in Brazil, and I am the Sole

Survivor.

May, in addition to being a messenger for the line, also operated the Robbers Roost Station. His brother Jim was the station attendant at the

May's Road Ranch station. May was born in Missouri in 1852. The date of his death is somewhat in question. William N. Hockett in his

Boone May — Gunfighter of the Black Hills states that May died in Rio de Janero in 1910. However, Bierce's

reference quoted above was published as a part of his Complete Works in 1909. The article was

apparently a newpaper column which had been published earlier.

Some men instinctively feared Boone May. One early diarist, Rolf Johnson,

wrote of coming across May in advance of the Sidney Stage,

[H]is eyes were a peculiar feature, being of an

indescribable hue between yellow, green, and grey, and

had a curious restless look about them. He was a man

I would instinctively fear without knowing who he was. Johnson, Rolf,

Happy As a Big Sunflower: Adventures in the West, 1875-1880,

Bison Books, 2000.

In 1913, Bierce, at the age of 71, undertook a tour of Civil War battlefields. In December of

that year, he was in Texas. Several letters to his neice suggest that it was his intent to go into Mexico which was then in

the throes of a revolution. On December 26, 1913, he wrote a letter from Chihuahua City. He was never heard from again. There is no

agreement as to Bierce's fate. The sole clue as to his intentions and where he planned to travel was the letter which, unfortunately,

has been destroyed with no copies being made. Some have indicated that the letter was to his long time

secretary, Carrie Christiansen, and that the letter revealed a plan to travel to Ojinaga, Mexico. Others indicate that the letter indicated

that his destination in Mexico was "unknown." Nor is there agreement as to whom the letter was addressed. Some writers have

indicated that the letter was to his neice Lora Bierce. In fact, there were several earlier

letters to his neice. In one, he wrote,

"Goodbye. If you hear of my being stood up against a Mexican stone

wall and shot to rags please know that I think that a pretty good way to

depart this life. It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar

stars. To be a gringo in Mexico -- ah, that is euthanasia."

Various writers have speculated that Bierce was killed in the seige of Ojinaga on January 11, 1914; that he was

executed by Pancho Villa; that he was suspected by being a spy and killed by federalistas in

Sierra Mojada; that he returned ill to Texas and died at Marfa, Texas; or

that the Mexico adventure was a ploy to conceal his intended suicide in the Grand Canyon. Other cite rumors that Bierce, notwithstanding that he would be

over 160 years old, is still wandering about the Sierra Madres. About the only theory that has not

been put forth, would be one that he ran away with Etta Place. Thus, Bierce achieved immortality by disappearing without

explanation into the pages of history.

Next page: Deadwood Stage Continued.

|