|

Mud Wagon, Ft. Bridger, 1860's

Although in most instances, a Concord coach was used, in some instances the conveyance was

a "mud wagon." As may be seen by the above photo, a mud wagon was a stage coach with canvas top and sides, so as to reduce

weight on muddy or rougher roads. It also cost only about half that of a

full Concord coach.

James F. Rusling, shortly after the Civil War, proceeded to the West Coast in one of the

stages. In his book, The Great West and Pacific Coast, he was at first impressed

by the comfort of the coach and the quality of the horses:

We found his [Holladay's] stages to be our well-known Concord coaches, and they quite surpassed

our expectations, both as to comfort and to speed. They were intended for nine inside--three

seats full--and as many more out-side, as could be induced to get on. Their teams were either four or six horses,

depending on the roads, and the distance between stations. The animals themselves

were our standing wonder; no broken-down nags, or half-starved Rosinantes, like our typical

stage horses east; but, as a rule, they were fat and fiery, and would have done credit to a

horseman anywhere. Wiry, gamey, and as if feeling their oats thoroughly, they

often went off from the stations at a full gallop; at the end of a mile or so would settle down to a

square steady trot; and this they would usually keep on right along until they

reached the next station. These "stations" varied from ten to twelve miles

apart, depending on water and grass, and consisted of the rudest kind of a

shanty or sod-house ordinarily.

The stage would ordinarily make a 100 or 125 miles a day, with the only stops the briefest

sort at the swing stations, merely to change the horses. As the stage approached the station,

the driver would blow a horn or give a loud wild "warwhoop," similar to a rebel yell, to alert the station attendant who would

then have the next team ready when the coach pulled into the station. With a fast change,

the stage was off again. The only stop for the benefit of the passengers would be a brief,

forty-minute stop for meals and a change of drivers at "home stations" located forty or fifty miles apart.

Onward, again, the stage would rumble, twenty-four hours a day with the passengers attempting

to sleep in their seats.

As indicated by General Rusling, the coach had in its interior three

bench seats, the one toward the front of the coach facing backwards. Seating was on a first come, first seated basis.

The last passenger might be the unfortunate one to have the center forward seat, facing backwards. The

swaying of the stage on the rutted, potholed roads could easily lead to a severe case of motion

sickness. The bench seats had a width of approximately four feet, meaning that each

passenger had a seat width of only 16 inches, about the same, or slightly greater, as the modern equivalent

of a stage, a commuter airline, and only slightly less than the 16 1/2 inches allocated in

the steerage section of a modern jetliner. Additionally, prior to the advent of oiled and

hard roads, the passengers were subjected in the summer to great clouds of

dust kicked up by the horses' hooves and by the wheels of the stage. The dust was

so great that passengers were warned against using hair oil which would become caked with the

dirt. Some lines would provide the passengers with "dusters" which would then be laundered

after each trip. During rainy weather canvas or oiled leather flaps would be lowered over the

"windows" to keep out the rain. Luggage and the mail would be strapped to the back and

covered with an oiled leather flap. When there was excess mail the bags would

be placed on the floor of the passenger area and the passengers would have to ride with

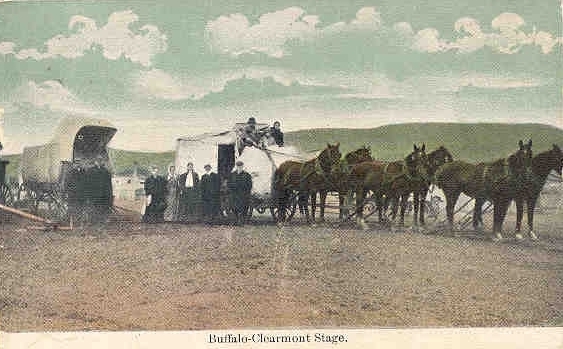

their feet on top of the bags and chins resting on their knees. As indicated by the next picture of the Buffalo-Clearmont

stage, in cold weather some lines would encase the coach in canvas in a vain attempt to

keep out the cold. Indeed, a crossing of the continent on the Overland in mid-winter was an

experience not to be savored. In some instances, passengers would wear buffalo overcoats, on top of which

would be buffalo robes. About their legs they would wear goat skin leggings.

[Writer's note: In the 1920's raccoon skin coats were all the thing but they were very

expensive. On one eastern campus (Cornell),

a salesman appeared who sold some very beautiful coats and and a much lower price than raccoon

skin coats.Many students paraded around in the new coats putting those who paid more for the

less attractive raccoon skin coats to shame; that is until

the first rain when the aroma of the new coats revealed to the world that they were goat skin

coats. The goat skin coats disappeared never to be seen again.]

Charles Farrar Browne (stage name, Artemus Ward) noted

that the trip by stage across Wyoming in winter was "sufficient reason for my election to any lunatic asylum, by an overwhelming vote...."

The coach, on runners because of snow, broke down and the passengers were forced to walk. Browne contined:

One of our passengers, a

fair-haired German boy, whose sweet ways had quite won us all, sank

on the snow, and said--Let me sleep. We knew only too well what

that meant, and tried hard to rouse him. It was in vain. Let me

sleep, he said. And so in the cold starlight he died. We took him

up tenderly from the snow, and bore him to the sleigh that awaited

us by the roadside, some two miles away. The new moon was shining

now, and the smile on the sweet white face told how painlessly the

poor boy had died. No one knew him. He was from the Bannock

mines, was ill-clad, had no baggage or money, and his fare was paid

to Denver. He had said that he was going back to Germany. That

was all we knew. So at sunrise the next morning we buried him at

the foot of the grand mountains that are snow-covered and icy all

the year round, far away from the Faderland, where it may be, some

poor mother is crying for her darling who will not come.

Buffalo-Clearmont Stage, approx. 1910

The ability to sleep under such circumstances was nil. Except for a bunk for drivers at the ends of their runs, there were

no sleeping accomodations at the stage stations. In September, 1866, Silas Seymour, the consulting engineer for the Union Pacific, and

Jesse L. Williams, an engineer and government director of the railroad, arranged to meet General

Dodge, chief engineer, and James A. Evans, the division enginer, on an inspection tour of proposed routes surveyed by Evans. The

participants had agreed to meet at the stage station at Laporte near present-day

Fort Collins. When Seymour arrived from Denver, he discovered to his horror that there were

no accommodations at the Laporte road ranch. He later wrote in his 1867

Incidents of a Trip Through the Great Platte Valley:

In view of such an emergency, Mr. Williams and myself had fortunately provided ourselves with

plenty of buffalo skins, blankets and ponchos. We therefore intimated

to the landlord, that one of us would occupy the lounge in the corner

of the dining-room, and the other would sleep on the floor by the stove.

Upon this the cook, a buxom middle-aged woman, with a sucking child, called

out from the kitchen, in not very gentle tones, that that lounge was her

bed. Mr. Chamberlain, an enterprising merchant in the vicinity, here came

to our relief, and kindly offered us the use of the floor in the back room

of his log-store, which we were very glad to accept.

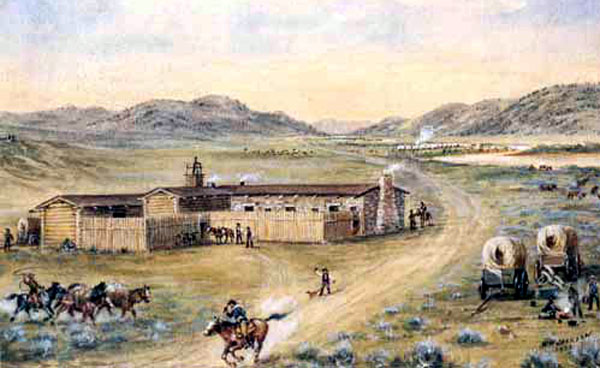

Devils Gate Station

As General Rusling's journey continued, he became less impressed with the coach, and after observing that the passengers' legs would become entangled, noted:

[Y]our friends on the front seat get their legs tangled and twisted up with yours,

or you get yours twisted and tangled up with theirs--you don't exactly know which; and, in

short, everybody wakes up chaotic and confused, not to say dismal and cross. Of course you

try it again after a while you wrap your robes still better about you, you adjust your legs more

carefully than before, and settling down again into your corner, think now you will surely

get a good sleep. However, you hardly get to nodding fairly, before there comes a repedition of

your former dismal experiences, and so the night wears on like a hideous dream. A series of unusualy

jolts and bumps disgusts every one with even the attempt to sleep, and presently all hands drift

into a general talk or smoke. The history of one night is the wretched history of all--only such

sucessive one, as you advance, becomes "a little more so." Long before reaching Fort Bridger, we were in a sort

of half-comatose condition, with every bone aching, and every inch of flesh sore, and with the romance of stage-coaching gone from us

forever. Now, if a man's body were made of india-rubber, or his arms and legs were

telescopic, so as to lengthen out and shorten up, perhaps such continuous

travelling would not be so bad. But, as it is, I confess, it was a great weariness of the

flesh, and looking back on it now, with the Pacific Railroad completed--its

express trains and palace-cars in motion--I don't really see how poor human nature

managed to endure it.

But the cold was not the only peril of stage travel in the winter. On Friday, November 15, 1879, three coaches of the

Wall and Witter Stage Line were scheduled to meet the morning South Park train in Weston, Colorado, to carry passengers destined for

Leadville. As could be expected in the Rockies, it was cold and snowy. The corduroy road to Leadville was one which should only be

negotiated during daylight. The train was some five hours late.

Although warnings were given by freighters that the route was dangerous, the passengers, rather than be further delayed until

the storm abated and realizing that the scheduled journey could be completed before nightfall, elected to

proceed. The line placed its most experienced driver, Thomas Cooper, on the box of the lead coach. Cooper, half Indian, had

served George Crook as a scout in Wyoming. Cooper would later serve on the Cheyenne and Black Hills Express, the famed

"Deadwood Stage." There, because of his skill on the reins particularly at night, he earned the appellation of

"Owl-eyed Tom." Indeed, it was said of him on the Deadwood run, "The nights were never too dark nor the roads too rough for "Owl-Eyed Tom." Indeed,

his skill later became legendary. In 1914, he gave a demonstration of driving a six-horse hitch stage at

the Wyoming State Fair in Douglas.

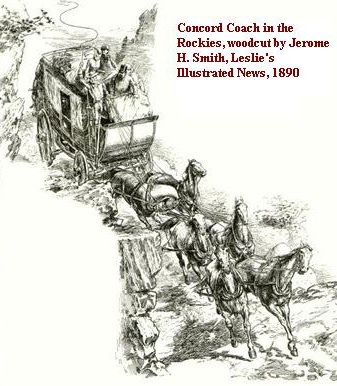

Crossing the Rockies, Theodore R. Davis, Harper's Weekly, 1868

In the lead coach besides the mail were 14 passengers, nine inside and five on top. Seated next to

Cooper on the box was the Reverend Joseph W. Pickett. The Reverend Pickett was a superintendent of missions for the

Congregational Church and was heading to Leadville as a part of his holy calling.

He previously had served in Cheyenne and Deadwood. When the stages finally left Weston, Colorado, at 12:00 noon,

it was believed that the storm had reached its peak and would soon abate. There was still time to complete the trip well

before sunset. The storm worsened. At times the horses could not be seen through the blowing snow. Passengers on the hurricane deck

of the coach would periodically alight from the coach and walk beside in order to warm up.

At Platte Station, Cooper advised the passengers that the journey ahead would be hard.

They could remain at the station.The passengers of the Number 2 Coach elected to stop. Freighters at the station advised that the

road ahead was not safe. Again,

believing that the storm would soon lessen and there being plenty of daylight left, the passengers of the

lead coach and the Number 3 coach insisted that they continue. At Davidson's Station, the passengers of the

Number 3 coach gave up with the passengers staying at Davidson's and the stage returned to Platte Station. The 14 passengers of the lead coach again

insisted that Cooper continue; there was still time to get to Leadville by nightfall. Ahead lay the 11,900 ft. summit of

Weston Pass. And beyond the pass was a treacherous stretch known as "Rocky Point" where many a stage driver and passenger had been

injured when a coach had slipped off the road and plummeted down the precipice beside the road. Indeed, the road was

so hazardous that the company paid its drivers $50.00 to $80.00 a month.

At the approaches to the pass, the stage encountered its second delay. A team on a preceeding

freighter's train was unable to pull a heavily loaded wagon up the slope. Thus, the road was blocked. A second team from a lead wagon had to be

unhitched and hitched to the stalled wagon in order for it to make it up the hill. With the obstruction removed,

the stage continued through the pass. It was still daylight but it was now too late to return.

On the far side of the pass, the road was again blocked by a stalled freighter. The road was not

reopened until sunset.

Eleven miles from Leadville, along Rocky Point, the stage began its descent down the hill in the

dark. The coach was only two miles from the warmth and safety of Nine-Mile House on the

Arkansas River. The horses were blinded by the snow in their eyes. Ice and snow jammed the

brakes on the coach. As Tom Cooper attemped to slow the team, the rear of the coach skidded sideways

on the built-up snow and ice towards the precipice.

Cooper grasped the reins tightly, perhaps hoping that the speed of the horses would straighten the

coach. The team broke loose. With Cooper's grasp on the reins he was pulled off the box and thrown

about twenty feet. Although Cooper dislocated his shoulder, this probably saved his life. The

coach skidded down the hill and overturned. Fortuitously, all the passengers within the

vehicle survived. The Reverend Pickett was less lucky. He became entangled in the boot cover and was, thus,

not thrown free. He was crushed by the weight of the heavy Concord coach. The injured passengers within

the coach were able to break a hole in the vehicle and get out. Two passengers and Cooper walked through the

raging blizzard to Nine-Mile House to obtain help. An individual at Nine-Mile House then walked the

nine miles to Leadville for assistance. A month later on another run, Cooper's stage wrecked when the team broke loose yanking

Cooper from the box. Following his service on the Cheyenne-Black Hills line, Cooper returned to Leadville where he worked on a line operated

by Luke Voorhees, former superintendent of the Cheyenne-Black Hills line. There, again, Cooper was injured when his coach wrecked when the brakes failed. Cooper retired.

Eleven miles from Leadville, along Rocky Point, the stage began its descent down the hill in the

dark. The coach was only two miles from the warmth and safety of Nine-Mile House on the

Arkansas River. The horses were blinded by the snow in their eyes. Ice and snow jammed the

brakes on the coach. As Tom Cooper attemped to slow the team, the rear of the coach skidded sideways

on the built-up snow and ice towards the precipice.

Cooper grasped the reins tightly, perhaps hoping that the speed of the horses would straighten the

coach. The team broke loose. With Cooper's grasp on the reins he was pulled off the box and thrown

about twenty feet. Although Cooper dislocated his shoulder, this probably saved his life. The

coach skidded down the hill and overturned. Fortuitously, all the passengers within the

vehicle survived. The Reverend Pickett was less lucky. He became entangled in the boot cover and was, thus,

not thrown free. He was crushed by the weight of the heavy Concord coach. The injured passengers within

the coach were able to break a hole in the vehicle and get out. Two passengers and Cooper walked through the

raging blizzard to Nine-Mile House to obtain help. An individual at Nine-Mile House then walked the

nine miles to Leadville for assistance. A month later on another run, Cooper's stage wrecked when the team broke loose yanking

Cooper from the box. Following his service on the Cheyenne-Black Hills line, Cooper returned to Leadville where he worked on a line operated

by Luke Voorhees, former superintendent of the Cheyenne-Black Hills line. There, again, Cooper was injured when his coach wrecked when the brakes failed. Cooper retired.

Other discomforts to relieve the boredom of the journey greeted the intrepid traveler. Although the

coaches were designed to float whilst fording rivers and streams, such crossings were not without

interest. George W. Pine in his 1873 book, Beyond the West, described his journey,

prior to the construction of the railroad, from Denver to Cheyenne in a mud wagon:

There are several large and interesting streams which cross our road, in fording one of which we were obliged to exercise our swimming ability,

while those who could not, hold on to the floating coach. The stream was very much swollen from the melting snows

in the mountains. The lead mules when about midway of the stream turned their faces

towards the driver, and became entangled in the harness, and the wheel team

so much so, by turning short round threw the stage quite over on one side, and the

body of it nearly filled with water, so that those inside found it quite

necessary to make a very hasty exit outside to find breathing room. As the current was

quite strong, all were carried down stream some distance before reaching the shore.

Soon, however, all were out without injury save a thorough drenching; but the hot sun and unusually

dry air very soon dried wet clothing. The team and stage out, we are soon on our

way again.

With this little experience we approached the other young river across the road with more precaution, the St. Vrains. Here everything was

removed from the stage, piled on a little flat raft and

ferried across the stream, and then three persons at a time. After baggage and passengers were over

the horses were swam over, and a long rope tied to the end of the stage tongue, when

a team drew it to the opposite shore.

Holladay's personal accommodations were, however, better. Eugene Ware described Holladay's

personal coach:

The coach was a sort of Pullman conveyance. They had a mattress on the

floor of the coach, and they slept in the coach, and when they rode,

they rode with the driver, and on a seat on the top. They had another

coach, in which there were servants, a cook, and supplies. Each

of these coaches was drawn by six horses, and went as fast as the fastest.

The advertised schedule from Salt Lake City to Atchison, 1200 miles, was eleven days. In once instance Holladay

made the trip in his personal coach in eight days, six hours. Indeed, however, the

speed with which Holladay's stages crossed the mountains and the plains was the wonder of the age. In

Roughing It Clemens wrote of an incident (probably apocryphal) in his journey to the Holy Land in which one of

his fellow pilgrims waxed eloquently to a young lad who but a few years before had crossed the

continent on the Overland:

"Jack, do you see that range of mountains over yonder that bounds the Jordan

valley? The mountains of Moab, Jack! Think of it, my boy--the actual

mountains of Moab--renowned in Scripture history! We are actually

standing face to face with those illustrious crags and peaks--and for

all we know" [dropping his voice impressively], "our eyes may be resting

at this very moment upon the spot WHERE LIES THE MYSTERIOUS GRAVE OF MOSES!

Think of it, Jack!"

"Moses who?" (falling inflection).

"Moses who! Jack, you ought to be ashamed of yourself--you ought to be

ashamed of such criminal ignorance. Why, Moses, the great guide, soldier,

poet, lawgiver of ancient Israel! Jack, from this spot where we stand, to

Egypt, stretches a fearful desert three hundred miles in extent--and across

that desert that wonderful man brought the children of Israel!--guiding

them with unfailing sagacity for forty years over the sandy desolation and

among the obstructing rocks and hills, and landed them at last, safe and

sound, within sight of this very spot; and where we now stand they entered

the Promised Land with anthems of rejoicing! It was a wonderful, wonderful

thing to do, Jack! Think of it!"

"Forty years? Only three hundred miles? Humph! Ben Holliday would have

fetched them through in thirty-six hours!"

Overland Coach, 1869, buffalo soldiers on top

Road agents and Indians also added interest to stage trips. During the Civil War, the

West was populated with many deserters from both armies who made their living violating the law.

In 1863, George Plumb, a young military officer had a

harrowing journey on the Overland Stage.

On July 7, 1863, he was a participant in an all day's

engagement with the Ute Indians in South Pass, in which several soldiers

were killed and several wounded. On his return to the fort he received orders to report to St. Louis. July 9,

1863, he took the stage. At Medicine Bow

the Indians had destroyed the station and the driver

refused to go on until Plumb agreed to ride shotgun.

The station at Rock Creek was also destroyed and the stage was required

to proceed on to the next station without a change of horses.

At "Cachlepowder" [Cache La Poudre] Plumb took

the eastbound Denver stage [At Camp Collins, now Ft. Collins, a branch line from Denver

met the Overland]. The stage had three passengers, one being David Moffat,

a first cousin once removed of the writer's grandfather. At the

Nebraska line, about two miles after Cottonwood Station, the coach was halted by road agents,

but Moffat threw open the

door on one side as did Plumb on the other. Both quickly

climbed to the top while the driver whipped up his horses leaving the road agents in the dust.

The rest of the journey was apparently uneventful.

In April of he same year, one of the fiercest attacks on the Overland Stage occurred along the Sweetwater.

Two heavily laden coaches were travelling together protected by an armed guaard of nine men. The first attack was

beaten off, but in wave after wave the attacks continued. Soon all of the horses were down in their

harnesses and the coaches were effectively stopped. A barricade was set up using the mail bags augmented by the

bodies of Indians that had been killed. The attacks continued until nightfall. Eventually, the men were able

to detach the body of one of the coaches from the chassis which was then pulled by those still able to stand to carry the remaining

wounded the Three Crossings. A party when out to the scene of the attack. The coaches were described as

stuck so full of arrows that they looked like gigantic pincushions. The mail sacks had been slit open. Thousands of

dollars of bonds and drafts were strewn along the trail. They were gathered up and forwarded to the

post office department in Washington and then re-sent to the original addressees marked "delayed en route." See,

Elwell, Robert Farrington: "The Story of the 'Overland Mail'," Outing Magazine, 1906, p. 62.

In May, another report came in of Indian attacks:

Headquarters Station,

Sweetwater Bridge,

Dak. Ter.,

May 23,1865.

Sir:

I have the honor to report that on the 20th instant, at 11 a. m., I received a telegram

from the operator at Three Crossings Station reporting that the Indians, in strong force,

had invested, and that they were at that moment firing on the station, and that the garrison

was very short of ammunition and could not hold out long. Ten minutes after the receipt of this

report the line went down.

Three Crossings Station, watercolor by William Henry Jackson.

The report continued.

At 12 o'clock m., with 1st Lieut. S. Bodwell and eighty-five men,

I started for the sceue of action, forty miles distant. At Split Rock I found the telegraph

line down, fifty feet gone. Reached Three Crossings at 8 p. in. and found that the Indians

had done no injury further than stealing one horse from the station. They withdrew and

crossed the Sweetwater River at 4 p. m. and immediately left the vicinity.

My command rested till daylight the 21st, when with twenty men I crossed the river and

followed the trail fifteen miles across an extensive plain, satisfying myself from their

movements—first, by their withdrawing from the station at so early an hour and apparent hurried

manner, as reported by the garrison, and their having not camped the ensuing night—that they

had information of my pursuit. I saw none, but estimate them at 200. Their trail went directly

toward Wind River, where I think they now are and where their families may be found. I arrived

in return at this station on the 22d instant at 8 p. in. Whole distance traveled, 110 miles.

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

JAS. E. GREER,

Captain, Commanding Station.

Lieut. L.I. Taber,

Acting Assistant Adjutant-General

Not even Ben Holladay, himself, was immune from road agents. On one

occasion returning east with his wife who was ill, his coach was stopped by two

road agents. While one agent searched the boot for the express box, the other agent stuck a shotgun in the window of the coach within a foot of Holladay's

nose, telling Holladay to keep his hands up and not move. Daring not to move, Holladay began to

develope one of those intolerable itches on his nose that comes when one may not move.

Ben Holladay developes an itch.

Holladay later related the incident: "'Stranger,' I said, 'I must scratch my nose! It itches so that I am almost crazy!'

'Move your hands,' he shouted, 'and I'll blow a hole through your head big enough for a jack-rabbit to jump through!'

I appealed one more.' 'Well,' he answered, 'keep your hands still and I'll scratch it for you.'"

"Did he scratch it?" asked one of the stagecoach king's listeners. "Sure," was the reply. "How?" asked the listener. "With the muzzle of the cocked gun.

He rubbed the muzzle of the cocked gun. He rubbed the muzzle around my mustache and raked it over the end of ny nose, until I thanked him and

said that it itched no longer." (As quoted by Root and Connelly, The Overland Stage to California, p. 560." Fortuitously, Mrs. Holladay managed to sleep through the entire incident. The road agents failed to notice the extra gilt with which Holladay's personal coach

was adorned, and got away only with Holladay's watch and gold chain, totally missing

a money belt which was well filled.

Wyoming's Bishop Ethelbert Talbot, however, described one occasion where there was, perhaps, divine

immunity from the depredation of a road agent. One of his fellow Episcopal bishops was traversing the

plains by stage and was the only passenger when the coach was stopped by a road agent. The driver

advised the road agent that the only passenger was a bishop.

"Well, said the robber, "wake up the old man. I want to go through his pockets."

When the Bishop was aroused from a sound slumber and realized the situation, he gently remonstrated with the

man behind the gun. He said:

"Surely you would not rob a poor Bishop. I have no money worth your while and I am engaged in

the discharge of my sacred duties."

"Did you say you were a Bishop?" asked the road agent."

Yes, just a poor Bishop."

"What church?"

"The Episcopal church."

"The hell you are! Why, that's the church I belong to. Driver, you may pass on."

As suggested by Plumb's journey, Indians became a problem during the Civil War. During the period 1864-1866,

nearly all stations for a 400 mile distance in Wyoming were destoyed, stock

was stolen by the Indians, and a number of coaches lost. Total losses amounted to $500,000 which the

goverment agreed to indemnify.

"The Missing Mail--An Incident of the Plains," Harper's Weekly, 1881.

For weeks on end, service was interdicted and, indeed, for a period of time in 1864, it became

necessary to carry the mails by ship to Panama and across the Isthmus and then up to California.

Notwithstanding the governmental agreement to indemnify against the Indian depredations, the bill appropriating

the funds lingered in Congress and finally died with Holladay's death in 1887.

With the pending completion of the Pacific Railroad and the losses from the Indian problem, Holladay sold out to

Wells, Fargo & Co. in November, 1866, for $2,000,000 plus $250,000 in stock in Wells Fargo. Holladay

then invested in steam navigation and railroads in which he lost his fortune.

His mansion in Washington was foreclosed upon and he died in Oregon in relative poverty.

Next page: The Overland Stage Continued, Jack Slade, Point of Rocks Station, Benjamin F. Ficklin.

|