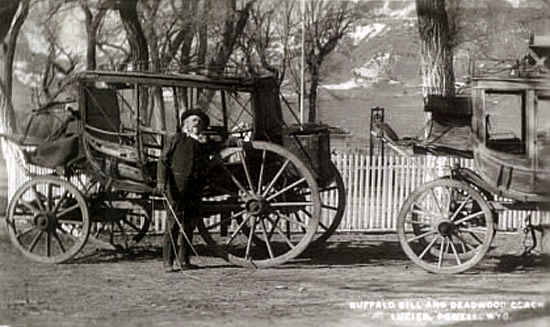

Col. Wm. F. Cody, next to Deadwood Stage parked at Cody's TE ranch, photo by A. G. Lucier. See text below.

The attack upon the Deadwood Stage was a centerpiece

of Wm. F. Cody's Wild West Show, photo of Cody next to Deadwood Stage,

above. The coach depicted was constructed by the Abbot-Downing Co., Concord,

N.H. in 1863 and was shipped to the Pioneer Stage Co., San Francisco, around Cape

Horn on the clipper ship General Grant. The coach was taken by Cody to Europe twice

where it was billed as the "Most Famous Vehicle Extant." Among those given

rides in the coach on its European tours was the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII.

The coach was purchased by Col. Cody in 1911 and is now on exhibit at the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody. See next photo.

Deadwood Stage, Buffalo Bill Museum, Cody, 2003, photo

by Geoff Dobson

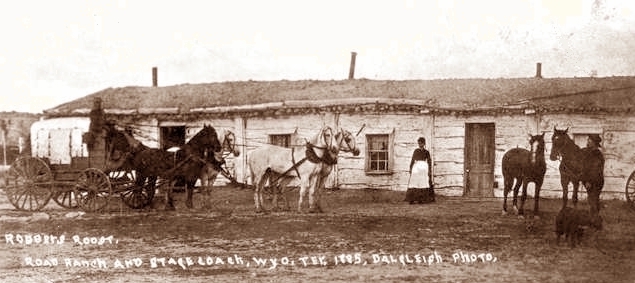

Robbers Roost Station, photo by Thomas Dalgleish, 1885.

Robbers Roost Station was about three miles north of

present day Mule Creek Junction. Thomas Dalgleish, brother of Colorado photographer George

Dalgleish, maintained a studio in Buffalo, Wyoming. For another view of a Deadwood stage, see view of

stage parked next to the Lusk Museum on subsequent page. The stage line initially ran from Cheyenne via Horse Creek,

Bear Springs, Chugwater, Chug Springs, Eagle's Nest, and Fort Laramie where the stage crossed the newly-opened

Military Bridge. At Hat Creek Station, north of present day Lusk, the stage road split, one branch continung

due north past aptly named Robbers Roost following the approximate line of present-day

U. S. Highway 85 into Deadwood. The other branch turned eastward at Hat Creek Station and followed

Spring Creek, turning northward to Custer City. The latter route was so dangerous that it

was shortly abandoned in favor of a more easterly route through Buffalo Gap and coming into the

eastern Black Hills. Indeed, one early correspondent for the New York Times described the

Indian Creek road as as "perfectly lined with rifle-pits, and occasional grave thrown in

to make one cheerful." The Indian Creek Station was a fortified dugout with rifle ports from which

its occupants could perforate Indians who came within range. The corral also was a dugout, allegedly to

protect the horses from marauding Indians. The road through Indian Creek Canyon in wet weather was

thick gumbo. One writer described his journey down Indian Creek:

[A]fter passing through a number of deep and miry water-courses, our teams swung around under the

shadow of a gread overhanging bluff of yellow earth, and we found ourselves upon the banks of Indian

Creek, which, our driver announced, was the most dangerous part of the whole journey.

The bed of the creek is about two hundred yards in width, and the banks are steep and high. Sharply outlined mounds of earth rise at

frequent intervals in the stream-bed, and form places of protection from which the

murderous savages may fire upon their unsuspecting victims, without any risk of being killed or wounded

them selves; moreover, the course of the creek is heavily timbered, so that it is almost impossible to distinquish forms

a short distance away.

* * * *

When the ground impregnated with alkali is damp or wet, it forms the most villainous clinging compound

imaginable. The revolving wheels quickly became sold masses of heavy mire, the spaces between the spokes and between the

wheel and the wagon-box being completely filled, so that every hundred yards or so

it beame necessary to dismount and pry it away with a crow-bar. In order to relieve the jaded

horses, the greater number of the passengers dismounted. But after half a dozen steps their boots would pick up great slabs

of the earth, and they too were forced to resort to the crow-bar.

Magazine writer Laura Winthrop Johnson, "Eight Hundred Miles in an Ambulance," Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, June 1875,

described the road northward from Cheyenne as:

over a succession of small creeks and divides. These table-lands were always

barren, and covered with the same thin gray vegetation, but sometimes

adorned with a few flowers—the beautiful agemone or prickly poppy, with its

blue-green leaves, large white petals and crown of golden stamens;

the pretty fragrant abronia, and the white oenothera. A deep pink

convolvulus was common, which grew upon a bush, not on a vine, and was a

large and thrifty plant. Sage and wormwood were seen everywhere, and on the

streams we found larkspur, aconite, little white daisies and lungwort,

lupines and the ever-present sunflower. But usually all was barren—barren

hills, barren valleys, barren plains. Sometimes we came upon tracts of

buffalo-grass, a thin, low, wiry grass that grows in small tufts, and does

not look as if there were any nourishment in it, but is said to be more

fattening than corn. Our animals ate it with avidity. Was not all this

dreary waste wearily monotonous and tame? Monotonous, yes; but no more tame

than the sea is tame. We sailed along day after day over the land-waves as

on a voyage. To ride over those lonely divides in the fresh

morning air made us feel as if we had breakfasted on flying-fish. We felt

what Shelley sings of the power of "all waste and solitary places;" we felt

their boundlessness, their freedom, their wild flavor; we were penetrated

with their solemn beauty. Here the eyesight is clearer, the mind is

brighter, the observation is quickened: every animal, insect and bird makes

its distinct impression, every object its mark. There is something on the

Plains that cannot be found elsewhere—something which can be felt better

than described—something you must go there to find.

Other travellers on the stage road complained of the monotony of the journey. Mrs.

Annie D. Tallent later wrote that the "opprobrium" of disgusting monontony was releved

"only be the superabundance of mud encountered at intervals, claiming our undivided attention." The Last

Hunting Ground of the Dakotahs, Nixon Jones Printing Co., St. Louis, 1899.

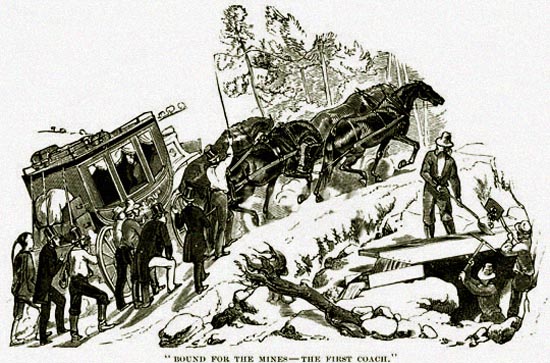

"Bound for the Mines, First Coach" Woodcut, Strahorn, Robert: Handbook of Wyoming, 1877.

In the Summer of 1876, unsuccessful several attempts

were made to reach Deadwood by stage from Cheyenne

but turned back due to the danger of marauding Indians following their

defeat of Custer at

the Little Big Horn.

Prior to mail being carried by stage, mail was carried by a private

mail service organized by Charlie Utter. Messages would be telegraphed from Cheyenne to Fort

Laramie, transcribed, and carried by express riders to Deadwood. To avoid the Indians, the messengers would

ride primarily at night. In this manner, messages could reach Deadwood from Cheyenne in only 48 hours. During its

three months of operation, Utter's service never lost any mail to the Indians although there may

have been a few harrowing moments.

The most dangerous part of the journey, however, was the night run near the

Hat Creek Station, north of Lusk. There, Big Nose George, see Rawlins, committed many of his

depredations.

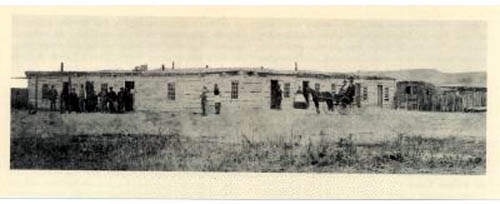

"Old" Hat Creek Station, approx. 1880.

The Old Hat Creek Station and Fort, established in 1875 by Capt. James Egan, was located north of the Hat Creek

Breaks on Sage Creek. Capt. Egan mistakenly believed he was on Hat Creek in Nebraska. Egan, an

Irishman, received a battlefield commission in the 2nd Cavalry during the Civil War, was wounded at Cold Harbor, and saw service in

the west from the end of 1865 until at least the late 1870's, being stationed at various times at

Ft. Lyon, Colo., Ft. Sanders, Ft. D. A. Russell, Ft. Laramie, and in Montana.

The fort burned in 1883. Subsequently a new

station was constructed a short distance to the west on Cottonwood Creek. The "new" station, still in

existence, was a log, two-story, hip-roofed structure.

Stations frequently would have all needed accommodations for

travelers, including corrals, blacksmiths, feed for the horses, etc. The larger, more elaborate stations were

referred to as "road ranches". The modern equivalent would be a truck stop with a motel. The

Ecoffey and Cuny facility, discussed on a subsequent page, started out as a road ranch, but was converted

to a hog ranch when there was a decline in business.

The "New" Hat Creek Station, 1909

About eight miles north the Hat Creek Stockade, Indians shot the a horse beneath one messenger, Brant Street.

Another ball struck the pommel of Street's saddle and a third

knocked the heel from his boot. Street took cover in an arroyo. There he and the Indians

exhanged fire until with darkness the Indians withdrew. Street then crawled out to his

dead horse, retrieved the mail pouches and carried them on his back to the stockade. On Sept. 25, however, Dave Dickey brought the first stage

into Deadwood. But certainly the danger from Indians remained. Indian attacks on

the stage stations were not unexpected and the corrals took the form of fortified stockades so

as to preclude theft of the horses. In one instance, "Indians" attacked a station and after

the horses were stolen, it was discovered that the "Indians" had opened the padlock on the corral with a duplicate key.

Division superintendent H. E. "Stuttering" Brown was killed ostensibly by Indians near

Old Woman's Branch of the Cheyenne. Stuttering Brown had previously been a freighter, ran a

road ranch west of Scott's Bluff, and a gambling den in Omaha.

There were those, however, who suspected that Brown's

murder was committed by William "Persimmon Bill" Chambers. Persimmon Bill was a reputed horse thief and

murderer who kept a shack near Cheyenne Crossing. He and Stuttering Brown had a

mutual dislike for each other and, thus, Persimmon Bill was suspected of the killing. Persimmon Bill was allegedly an associate with the

notorious horse thief Henry "Dutch Henry" Born (1849-1921). Persimmon Bill was also

suspected of complicity in the 1876 stealing of some $10,000.00 worth of

Kentucky Whistkey being shipped to Deadwood by Charles Sasse & Company. Sasse's wagon train of

25 wagons and 100 mules loaded with the whiskey had camped in Red Canyon. During the night all of the

mules were run-off leaving the wagon train stranded and subject to the larceny of the cargo.

Periodically thereafter, the Kentucky whiskey would show up in Deadwood. Persimmon Bill's fate is subject to debate.

According to Patricia Jahns, The Frontier World of Doc Holliday: Faro Dealer from Dallas to Deadwood,

he was killed by Boone May. May is discussed on a subsequent page. According to Dan Thrapp, Persimmon Bill was hanged in

Tennessee. Dutch Henry, originally from Wisconsin, received his name as a result of his

German accent recieved from his German immigrant

parents. According to Charles Kelly, The Outlaw Trail, Dutch

Henry was killed by a partner in crime, Ben Tasker from Centerville, Utah. Dutch Henry's body was burned by

Tasker at Desert Spring, Utah. The remains were identified by his derringer found in the ashes. In actuality,

however, Dutch Henry met up with Hanging Judge Parker and was sentenced to twenty years in the

Arkansas Penitentiary. When he got out, he prospected for gold near Creede Colorado with a partner. His

partner froze to death. Dutch Henry returned to Wisconsin, married, and with his bride returned to

Pagosa Springs, Colorado, where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Brown's Hotel, Ft. Laramie, 1868. Photo by

Alexander Gardner (attributed). Note sod roof.

With the opening of the line, a new hotel was constructed at Fort Laramie for the passengers, the Rustic Hotel. On

the north side of the newly opened Military Bridge was the older log and sod Brown's Hotel operated by

William H. Brown. At first, the Rustic Hotel was regarded as a first class

operation with fine linens and dining room. Soon, however, complaints were

received from guests about a problem, bedbugs. The problem grew to such a

point that the fort's commander had to take matters into his own hands and

ordered the hotel to be fumigated. Another difficulty also arose. The hotel's corral

polluted the fort's water supply. From Ft. Laramie the stage road proceeded northward

though Indian and outlaw territory to Rawhide Buttes and Hat Creek north of Lusk (pictured on next page). At the Cheyenne

River, the road split. One branch continued north past Robbers Roost Creek, Jenny's Stockade and along Beaver Creek and on

in to Deadwood. The other branch followed the Cheyenne into Dakota Territory and up to

Custer City, Gayville and into Deadwood.

Sign along old Deadwood Stage Road near Edgemont, South Dakota. Photo courtesy of Bob Vance.

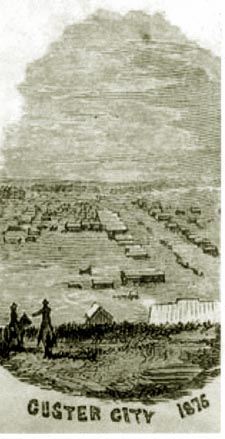

Custer City, 1876, from Strahorn's Handbook of Wyoming

Custer City, 1876, from Strahorn's Handbook of Wyoming

Prior to

the coming of the stage line, other than the hotel at Ft. Laramie, the traveler northward of Cheyenne found few if any

places of public accommodation, no road ranches, no taverns. Mrs. Johnson in her account of her 1874 trek northward to visit

the Indian agencies, describes having to camp at night. Along the way, she writes of the

nightly ritual of picking the burrs out of one's clothes, the evening repasts being blown away by whirlwinds coming off

Rawhide Buttes, and in the evening, as "a blood-red sunset flames from the horizon to the upper sky: and as it darkens,

and the wolves begin to howl, we think of * * * all the wild stories we have heard of

robbers and fights and Indian massacres."

Opening the line required the construction of swing stations and home stations to

service the stages and their passengers. As indicated by the photos on subsequent pages, most were crude

affairs constructed of logs and sod.The station at Running Water, as an example, was a soddie.

Advertisements for road ranches along the road may have raised a traveler's expections. Jack

Bowman's Hat Creek Station claimed in one ad that the table was "supplied with the best of everything."

John Phillips's "Regular Eating Station for Stage Passengers" claimed that it featured the

"Best of Board." In actuality, food at road ranches typically consisted of either beans and beef served separately or

beans and beef served together from communal platters "boarding house style." That, of course,

led to boarding house reach, and one better be quick about it or go hungry. The dinnerware, according to

one passenger, consisted of chipped blue enamelware which was usually greasy. The conditions led to the old joke about the passenger

who complained about the cleanliness of the towel and was told, "Twenty-six men used it before and

you're the first one that complained.

Phillips' "best of board" may have had a slightly different meaning. He provided accommodations. Beds in

road ranches providing overnight accommodations were frequently furnished with "beds" which consisted of

a platform equipped with boards upon which reposed a straw mattress. Men would frequently sleep on the floor using

their carpet bag as a pillow. Blankets in most instances were never washed.

Edward Gillette, after whom Gillette, Wyoming, is named, noted that the "hotels" also were not well heated. He wrote:

Travelers stopping at these flimsy places used to

make a grab for their clothes in the morning and rush to the

office, where there would be a big box stove with a roaring fire to

keep a man from freezing. One very cold morning a farmer came into the office

with icicles dangling from his whiskers, and a salesman who had

spent the night in the hotel asked him, "Which room did you have?"

Sir Samuel Baker in Wild Beasts and Their Ways, Macmillan, London, 1890, commented as to

a different discomfort in one road ranch on the Rock River to Fort Custer line, the vermin;

When the lamp was extinguished, the bed was alive. I always marvelled at the phrase,

"he took up his bed and walked," but if the bugs had been unanimous,

they could have walked off with the bed without a miracle.

Sleeping was impossible. I relighted the paraffin lamp, a retreat was evidently

sounded, and the enemy retired. Presently an explosion took place—the lamp had gone wrong,

and burst, fortunately without setting the place on fire. An advance was sounded,

and the enemy came on, determined upon victory.

I never slept in one of those prairie stations again, but we preferred a camp sheet

and good blankets on the sage-bush, with the sky for a ceiling.

And even at the end of the journey, the hotel accommodations in Deadwood City might be regarded

as less than first class. Ranchman Edgar Beecher Bronson in his 1906 Reminiscenses of a Ranchman after two days on

the stage checked into the Grand Central Hotel in Deadwood City but could not sleep for the

sounds of the rats in the walls. He threw a boot at the wall. To his embarrassment, the boot

went right through the wall made of cotton sheeting and paper and hit the guest in the next room.

Passengers were left to their own to relieve the boredom. On Bronson's journey, his fellow passenger was

"comfortably drunk." Part of the journey was on the sabbath. Therefore, the two amused themselves with

the singing of hymns. The coach proceeded northward to the sounds of the two singing "Shall we gather at

the River," "A Charge to Keep I have," and "From Greenland's Icy Mountain." Bronson's fellow passenger continued

to imbibe. Finally, the two sang the old hymn "I Hunger and I Thirst." The fellow passenger passed out as they came to the words,

"Thou true life-giving Vine,

Let me Thy sweetness prove."

Deadwood Stage continued on next page.

|