Stereograph, The Nelly Peck

on left, the

Far West, on right, undated.

In 1876, the Far West, under the command of

Captain Grant P. Marsh, was under charter to the Army and was being used as

a mobile headquarters for General Terry on the Yellowstone. The vessel, constructed

in 1870 in Pittsburgh was 190 ft. in length, and 20 ft. in width, and was ideally

suited for use in western waters drawing only 20 inches when unladen.

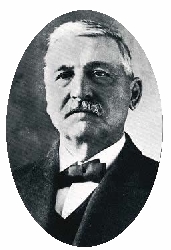

Captain Grant P. Marsh

Captain Grant P. Marsh

In the 1870's communications in northern Wyoming Territory, eastern Montana, and

Dakota Territory, notwithstanding the invention of the telegraph, institution of

railroads, and operation of stage lines, were no better and, in fact, worse

than communications in the 6th Century B.C. when Cyrus the Great created a system

of mounted relay stations to carry imperial communications. By the time of

Rome, relay stations were established on post roads, enabling messages to be carried

170 miles in a day. In 1861, the telegraph line had been stretched to the Pacific Coast. Yet except in

Utah where Brighan Young had connected all Mormon communities to the Deseret Telegraph

Line fron Idaho to northern Arizona, messages on the Western Frontier still had to be carried by hand.

Indeed, even though the Civil War was the first war to make extensive use of

the telegraph, even at its end communication was painfully slow. Thus,

as an example, in 1865, President Davis commissioned emissaries to negotiate

with the western Indians and bring a lasting peace to the Great Plains. Accordingly, on

May 1, 1865 representatives of the Apache, Pawnee, Osage, Kickapoo, Washita, Kiowa,

Commanche, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Navajo, and Sioux, gathered at Washita on the Confederate

Western Frontier. There, the representatives of the southern Great Father and the tribes

signed a treaty, none knowing that the Great Father had already fled his

capital in advance of the hosts of the northern Great Father. Indeed, in Indian

Territory the last Confederate civil and military forces did not surrender until

the middle of July.

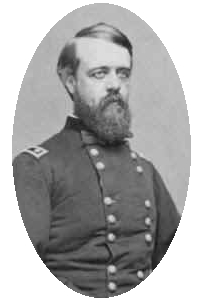

Alfred H. Terry Alfred H. Terry

Thus, by 1876 the closest telegraph lines to the Little Bighorn were at

Ft. Ellis, over 200 miles to the west; Ft. Fetterman to the south; Camp Stambaugh near

South Pass City; and Bismarck, 700 miles to the east. This made coordination of military movements between

different forces difficult, since as discussed with regard to Ft. Fetterman, it was

proposed the have a three pronged attack upon the Indians, one prong led by

General Gibbon coming from Fort Shaw to the west, Terry and Custer coming from Fort

Abraham Lincoln to the east, and Gen. Crook coming north from Fort Fetterman.

Later in the attempt to capture Geronimo in Arizona, Gen. Miles attempted

to alieviate the problem of communication through the use of the heliograph.

Other difficulties existed with communication. On July 11, the New York Tribune published a

dispatch from its "occasional correspondent," dated June 21, which described one of the

hazards of mail:

ROSEBUD AND YELLOWSTONE RIVERS, June 21. --

My last letter was written at the mouth of the Powder River shortly after the arrival

of Gen. Terry's expedition there. The mail was taken by the steamer Far West, Capt. Grant Marsh, to

the stockade, thence to be sent to Fort Buford by the Mackinaw boat. An

unfortunate accident occurred just as the bag had been put in and the boat was cast loose. The rapid current

of the river carried it against the steamer and it capsized. Sergeant Fox, an old

soldier from Fort Buford, was drowned. The mail, though wet, was

recovered and forwarded.

For discussion and description of Mackinaw boats, see Rendezvous.

The "occasional correspondent" for the Tribune was possibly Custer himself.

Custer had been known to have anonymously provided dispatches to newspapers. Custer in a letter

to Mrs. Custer relates the same incident as to the possible loss of his mailbag. Fortunately, a young correspondent and telegrapher recognized

Custer's mail. Thus, it was rescued and dried out by Capt. Grant and others. One of the

items in the mailbag was an article being sent to The Galaxy, a monthly magazine for

whom Custer had been providing his Memoirs.

In light of Custer's subsequent failure to await the arrival of Gibbon and Custer's own division of his

forces, the articles contain a certain irony. In the October, 1876, article received by the

magazine following Little Bighorn, Custer blames McClellan's failure to proceed against Richmond on

Lincoln's dividing the armed forces. Custer asks, "What general commanding an army at any

later period of the war, confronting the enemy and about to engage in battle upon

matured plans, would have been willing to risk a general engagement with his

army reduced unexpectedly more than one-third on the very eve of battle?" "War Memoirs," The Galaxy. Vol. XXII --

October, 1876 -- No. 4, p. 451. We, perhaps, now know the answer.

Intriguingly, in the last line of the article, the last line ever written by

Custer for publication, Custer suggests that his later

fame was as a result of an incident on a small stream easily forded by horses and in places

scarcely ten yards in width, "the Chicahominy river, a stream which, however chargeable with some of the

misfortunes of the Army of the Potomac, was almost literally a stepping-stone for my

personal advancement." The incident on the Chicahominy: The overly cautious George

McClellan was dithering about the depth of the river. A young impetuous lieutenant spurred

his horse into the middle of the stream heedless of the danger, "That's how deep it is, General!" Thus, Custer's

career began as it ended, upon impulse without forethought.

Mitch Bouyer, see text lower on page.

Mitch Bouyer, see text lower on page.

By June 27, General Terry had picked up disturbing accounts from Indian Scouts that

disaster had overtaken George Armstrong Custer's force. Terry directed the Far West to

be moved to the mouth of the Little Bighorn. On June 25, not waiting for

additional forces from John Gibbon as would have been indicated by previously formulated plans,

Custer divided his forces into three battalions. In the afternoon, Major Reno's allegedly

caught the last sight of Custer on a distant ridge. In the mid afternoon, two messages were

delivered to Captain Fredrick Benteen , a request delivered by Sgt. Daniel Kanipe that the mule train be moved

forward with reserve ammunition and the message delivered by Custer's bugler Pvt. John Martin,

"Benteen come on. Big village. Be quick. Bring packs. P.S. Bring pacs."

Martin (18 ? - 1922) was an Italian immigrant, originally Giovanni Martini, who spoke but

poor English. Martin prior to his immigration to the United States, served as Garibaldi's Tamburino, drummer,

in the Trentino campaign of 1866. The campaign was a part of the Third War of Italian Unification against

Austria which held the Trentino now a part of Northern Italy. Garibaldi was

successfully pushing the Austrians back when he received orders from General La Marmora to retreat.

Garibaldi responded with his famous obbedisco, "I obey." Thus,

Trentino remained a part of Austria until World War I. Following the

end of the Italian Wars of Unification, Martin allegedly abandoned a wife and child and came

to the United States, enlisting in the Army in 1874. In the Army a bugler also acted as

an orderly and, thus, it would not be unexpected for the bugler to deliver a message. The date and

location of Martin's birth is uncertain. At least four different areas of Italy claim to be

his birth place: Sala Conizalina, Apricale, Liguria, and Romagna. Different dates of birth are

given ranging from 1841 to 1852. He remained in the Army serving in Cuba during the

Spanish-American War. Following that war, Martin allegedly abandoned a wife and

three children in Baltimore City and moved to Brooklyn. He retired from the

Army in 1904 and eventually took employment as a ticket taker for the New York subway system at

the 103rd Street Station. He died on December 24, 1922 after being struck by a truck.

As we are aware, Benteen and Reno ran into problems of their

own and were not able to join Custer.

Boston Custer

Boston Custer

With Custer there were approximately 250 men, including

his brothers Tom and Boston, as well as his nephew Autie Reed and brother-in-law

James Calhoun. Autie had just turned 18 on April 27th. When Martin's message came, Boston and Autie were with the

pack train. They rode off to join George and Tom Custer. To some extent,

the expedition was like a family reunion. In several letters to his wife, Libby, Custer writes of playing jokes

on "Bos." In his letter of June 17, he wrote:

We all slept in the open air around the fire, Tom and I under a fly, "Bos"

and Autie Reed on the opposite side. Tom pelted "Bos" with sticks and clods

of earth after we had retired. I don't know what we would do without "Bos"

to tease.... Yesterday Tom and I saw a wild-goose flying over-head quite

high in the air. We were in the bushes and could not see each other.

Neither knew that the other intended to fire. Both fired simultaneously,

and down came the goose, killed. Don't you think that pretty good shooting

for rifles?

Teasing between the brothers was nothing new. In the 1874 expedition, George and Tom Custer scared

the wits out of their younger brother when he was riding alone by pretending to be Indians. On

another occasion they secreted a rattle snake in a trunk so as to frighten anyone who sat upon the

trunk. There are some indications that Custer himself regarded the 1876 expedition as more of a

junket rather than a dangerous military campaign. He invited naturalist George Bird Grinnell and

noted world traveller the Earl of Dunraven and the Earl's cousin Dr. George Henry Kingsley along. Grinnell

declined the invitation. Dr. Kingsley had written Mrs. Kingley from America indicating that

the Earl and Kingsley had accepted the invitation. Mrs. Kingsley had considerable angst. News of

the massacre reached Mrs. Kingsley before a

subsequent letter from Dr. Kingsley relating that the two had been unable to join the campaign because

of bad weather.

But the Custer Brothers were not the only ones who treated the expedition as

somewhat of a lark and frolic. The New York Tribune correspondent noted the

dispatch of June 21, that crewmen on board Gen. Terry's supply steamer Far West

panned for gold along the Yellowstone River with a show of "colors."

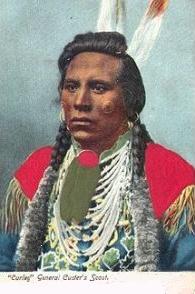

White Swan and Curley, Sheridan, Wyo., Oct. 1903, photo by B. C. Buffum.

Photo courtesy of and copyrighted

by Ben and Mary Sue Henszey.

White Swan and Curley, Sheridan, Wyo., Oct. 1903, photo by B. C. Buffum.

Photo courtesy of and copyrighted

by Ben and Mary Sue Henszey. For information as

to B. C. Buffum, see Cheyenne.

Accompanying Custer and his forces after their separation from Benteen and Reno

were four Crow Scouts: Curley, Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and White Man Runs Him. two crow scouts remained

with Reno, Half Yellow Face and White Swan.

When Custer's troop came into contact with the Indian village, the scouts were excused;

they had done their job. Among them, Curley refused to leave. Nevertheless,

Mitch Bouyer [sometimes spelled "Boyer"], one of Custer's mixed-blood French and Lokota

guides, insisted that the 17 year old Curley depart, allegedly telling Curley that

"We have no chance at all," and relay the message to Terry that "all are killed." In 1983, archeological

exploration of the battlefield was conducted. Previously unidentified remains were found. Using

modern forensic science, the remains of Boyer were identified.

Curley departed and was, thus, was able to observe the battle with a spy glass

from a ridge about a mile and a half away. He then eluded the Sioux by

crawling through coulees until he found the pony of a dead Sioux, taking the Sioux' pony

and blanket, he then rode two and a half days until he found the Steamboat Far West, where through sign

lanquage and drawing he was able to disclose the disaster. Because of language difficulties, however,

the extent of the disaster was not fully realized.

Curley, undated

Curley, undated

The following day, June 28, a rider appeared on the bank of the river being chased by Indians. Making it on

board, the rider, H. M. "Muggins" Taylor, bore a message from Gen. Terry giving the extent of the

Disaster. Terry later reported that scouts had been sent out about midnight

on the 25th:

The scouts were sent out. At half past four, on the morning of the 26th, they discovered

three Indians, who were at first supposed to be Sioux, but when overtaken they

proved to be Crows who had been with General Custer. They brought the first intelligence of the

battle. Their story was not credited. It was supposed that some fighting, perhaps

severe fighting, had taken place, but it was not believed that disaster could have

overtaken so large a force as twelve companies of cavalry.

[Writer's note: The three scouts were apparently Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and White Man Runs Him,

who had been excused when Sitting Bull's camp was reached.]

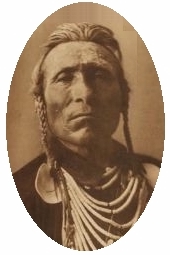

Hairy Moccasin, 1907.

Hairy Moccasin, 1907.

Hairy Moccasin, along with White Man Runs Him and Goes Ahead, were orignally assigned to

Major Reno's unit, but were reassigned to Custer's unit on June 25. After they were dismissed by

Mitch Boyer, they participated in the Hill Top Fight before making good their escape were they joined

Strikes the Bear, before meeting up with Col. Gibbon's unit.

On the evening of July 27, the full extent of the disaster was realized by Gen. Terry and a dispatch was prepared and

given to Muggins Taylor to be taken to the nearest telegraph at Ft. Ellis. Taylor had

received his nickname as a result of his love of the card game "Muggins." Taylor later served

as a deputy sheriff in Coulson, Montana, where he was killed in 1882 when attempting

to stop a domestic disturbance in a laundry.

Taylor was intercepted by Indians and had to hide in among some rocks overnight. The next morning, he made

good his escape and was pursued to the Far West. He remained on board

until the 29th, when he resumed his ride toward Ft. Ellis 229 miles away.

On July 3rd the dispatch was delivered, pursuant to instructions, to Capt.

T. D. Bonham, who, in turn, filed it with the telegraph office. The next day, Capt. Bonham checked with the office

to see if it had been sent, but the office was closed, it being the 4th of July.

The next day, Capt. Bonham checked on the status of his dispatch and

was advised that the line was down and he was told to send

the dispatch by mail to Chicago. Thus, General Terry's report did not

reach Chicago until 1:10 a.m. on July 7. From there it was relayed to

Gen. Sheridan at the Continental Hotel in Philadelphia arriving on July 8, long after

the dispatches from the Bismarck Tribune had been published in

eastern papers. Sheridan, in turn,

forwarded the report to Gen. Sherman at the War Department in Washington.

Goes Ahead, photo by Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952).

Goes Ahead, photo by Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952).

______________________________

[TELEGRAM]

Philadelphia, July 8, 1876

General William T. Sherman, Washington, D.C.:

The following just received from Drum, and forwarded for your information,

----------

Chicago, Ill., July 7, 1876 --- 1.10 a.m.

General P. H. Sheridan, U.S.A.,

Continental Hotel

The following is General Terry's report, received late at night, dated

June 27:

"It is my painful duty to report that day before yesterday, the 25th instant,

a great disaster overtook General Custer and the troops under his command.

At 12 o'clock of the 22nd instant he started with his whole regiment and a

strong detachment of scouts and guides from the mouth of the Rosebud;

proceeding up that river about twenty miles he struck a very heavy Indian

trail, which had previously been discovered, and pursuing it, found that it

led, as it was supposed that it would lead, to the Little Big Horn River.

Here he found a village of almost unlimited extent, and at once attacked it

with that portion of his command which was immediately at hand. Major Reno,

with three companies, A, G, and M, of the regiment, was sent into the valley

of the stream at the point where the trail struck it. General Custer, with

five companies, C, E, F, I, and L, attempted to enter about three miles

lower down. Reno, forded the river, charged down its left bank, and fought

on foot until finally completely overwhelmed by numbers he was compelled to

mount and recross the river and seek a refuge on the high bluffs which

overlook its right bank. Just as he recrossed, Captain Benteen, who, with

three companies, D, H, and K, was some two (2) miles to the left of Reno

when the action commenced, but who had been ordered by General Custer to

return, came to the river, and rightly concluding that it was useless for

his force to attempt to renew the fight in the valley, he joined Reno on

the bluffs. Captain McDougall with his company (B) was at first some

distance in the rear with a train of pack mules. He also came up to Reno.

Soon this united force was nearly surrounded by Indians, many of whom armed

with rifles, occupied positions which commanded the ground held by the

cavalry, ground from which there was no escape. Rifle-pits were dug, and

the fight was maintained, though with heavy loss, from about half past

2 o'clock of the 25th till 6 o'clock of the 26th, when the Indians withdrew

from the valley, taking with them their village. Of the movements of

General Custer and the five companies under his immediate command,

scarcely anything is known from those who witnessed them; for no officer

or soldier who accompanied him has yet been found alive. His trail from the

point where Reno crossed the stream, passes along and in the rear of the

crest of the bluffs on the right bank for nearly or quite three miles; then

it comes down to the bank of the river, but at once diverges from it, as if

he had unsuccessfully attempted to cross; then turns upon itself, almost

completing a circle, and closes. It is marked by the remains of his

officers and men and the bodies of his horses, some of them strewn along

the path, others heaped where halts appeared to have been made. There is

abundant evidence that a gallant resistance was offered by the troops, but

they were beset on all sides by overpowering numbers. The officers known

to be killed are General Custer; Captains Keogh, Yates, and Custer, and

Lieutenants Cooke, Smith, McIntosh, Calhoun, Porter, Hodgson, Sturgis,

and Reilly, of the cavalry. Lieutenant Crittenden, of the Twelfth Infantry,

along with Acting Assistant Surgeon D. E. Wolf, Lieutenant Harrington of

the Cavalry, and Assistant Surgeon Lord are missing. Captain Benteen and

Lieutenant Varnum, of the cavalry are slightly wounded. Mr. B. Custer, a

brother, and Mr. Reed, a nephew, of General Custer, were with him and were

killed. No other officers than those whom I have named are among the killed,

wounded, and missing.

It is impossible yet to obtain a reliable list of the enlisted men killed

and wounded, but the number of killed, including officers, must reach two

hundred and fifty. The number of wounded is fifty-one. The balance of report

will be forwarded immediately."

R. C. DRUM,

Assistant Adjutant-General

P. H. Sheridan,

Lieutenant General

----------

Supplementary report from General Terry, received at War Department at 12

o'clock, m.

[illegible] list of the enlisted men killed and wounded, but the number

of killed, including officers, must reach two hundred and fifty. The number

of wounded is fifty-one. The balance of report will be forwarded

immediately."

R. C. DRUM,

Assistant Adjutant-General

P. H. Sheridan,

Lieutenant General

----------

Supplementary report from General Terry, received at War Department at 12

o'clock, m.

Philadelphia

The Far West was not able to leave for

Bismarck until the 30th after Reno's wounded were loaded on the deck of the Far West, where

members of the 7th Cavalry Band acted as medics.

The vessel was then able to steam the 710 miles in only 54 hours, arriving at

Fort Abraham Lincoln at 11:00 p.m. on July 5.

At 2:00 a.m., Capt. William S. McCaskey, summoned all officers to his quarters at

Ft. Lincoln and read the dispatch from Capt. Edward W. Smith, General Terry's

adjutant. At 7:00 a.m. Capt. McCaskey, accompanied by Lt. Charles Gunley, and Post Surgeon,

Dr. J. V. D. Middleton, broke the news to Mrs. Custer and the other women members of the

Custer family. Although the day was hot, Mrs. Custer required a wrap and shivered. Mrs. Calhoun

apparently failed to comprehend that her husband, brothers, and nephew were gone, ran after

Capt. McCaskey, asking, "Is there no message for me?"

Next page: Reno and Benteen.

|