|

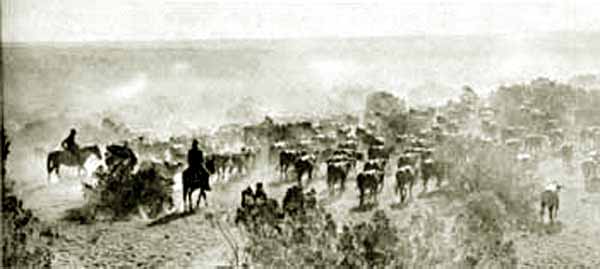

Texas Trail Herd, C. M. Russell

If the drovers were following the Goodnight-Loving Trail across the Llano Estacado, the "Staked Plain" so called

allegedly because early Spanish explorers had to mark their trail with stakes, a dificulty after leaving the

Middle Branch of the Concho was an 80 to 90 miles "dry drive" until Horsehead Crossing was reached.

Horsehead Crossing. Artwork by G. B. Dobson based on

National Park Service photo.

Horsehead Crossing took its name from the extaordinary number of horse, mule and cattle skulls found at the

crossing.

Dry drives created

their own problems. Teddy Blue Abbott explained:

"The trail boss had to do more riding than any of the rest of the outfit, for he

had to know where water was a day ahead of reaching it. As we were always going

into new country, it kept him guessing, as all drives were made according to where

water was. Some would be long and others short. We would have dry drives 40 miles

long. After he had watered on a long drive like that, the boss would push his herd

along the trail away into the night. The next morning, if the wind was in the north

we were all right, for the herd couldn't smell the water we had left behind, but if

it blew from behind we had our work cut out. for they would try to break back to

water again. If the herd got away and back to water, we felt that we had lost our

reputations. Cattle, when the wind is right, can smell water 50 miles away, old

cowpunchers believe. As quoted by C. M. Russell, Back-Trailing on the Old Frontiers,

Great Falls, 1922.

Texas Cattle watering at River, E.E. Smith.

In 2009, an early cattle drive

from the Mexican border to Saskatchewan was replicated, the first such cattle drive in over 100 years. The drive took from April 17 until September 2.

In one area of New Mexico, the drovers came across a sight which indicated the perils of a dried up water hole.

Bob Vance on Prince Sagenfurst at a dried up water hole, New Mexico.

At the end of a long dry drive, it was necessary for the trail boss to time arrival at the water. Tddy Blue continued:

"Then there was another chance for trouble in watering a herd.

The trail boss had to hit a big river just at the right time of day. If the sun

reflected in their eyes and there was enough breeze to make waves the longhorns

wouldn't take the water. In '83 a well known trail boss, Johnny Lea, was four days

crossing the Yellowstone River with a herd because of a scare they got.

John Lea was later foreman for the Circle Bar on the Little Missouri. Others who were employed on the Circle Bar included

Harvey "Kid Curry" and Hank Curry.

On the trail besides the dangers, the

cowboys were faced with dust, heat, and boredom. At the rear of the herd the least experienced rode drag. Their

job was to prod along the slow, the infirm, or the lazy cattle. Occasionally,

a cow would drop out to give birth to a calf. Since new born calves could not

keep up with the herd, it was an unpleasant duty of the drag riders to dispatch the calves and

drive the cow back into the main herd. At the back of the herd the dust was such that the

color of the men's clothes could scarely be discerned.

Dust kicked up by a trail herd.

Indeed, as recalled by one cowboy,

Ben Kinchlow:

I went up the Chisholm Trail five or six times. Charley Word, Blocker,

George West, W.G.B. Grimes, Abel an' John Pierce was all big trail drivers

then. Goin' up the trail you never was out of sight of a herd. The trail

was so worn, that the dust would be knee deep to the cattle. You could ride

right up to the rear of the cattle an' you couldn't see the cattle for the

dust.

Riding Drag, undated

To the sides of the herd would ride the flankers and ahead of them the swingmen whose jobs were to

keep the herd aligned. The dust was hardly less and in some instances they faced the incredible heat

given off by the herd.

At the front of the herd several of the more experienced rode point, for it was

there that the more rambunctious cattle would be found. It was the

job of the pointmen to keep the herd aimed correctly. Leading the herd was the lead steer or "bell ox." the most famous of

which was Charles Goodnight's "Old Blue." Old Blue, according to J. Frank Dobie, The Longhorns, 1941, "was known from the Pecos

to the Arkansas, in Colorado as well well as in Texas. He knew the trail to Dodge City bettr than hundreds of cowboys who galloped up its Front Street." Not only did Dobie

wrote of Old Blue but accounts of the steer appeared in J. Evetts Haley's 1936 charles Goodnight, Cowman and Plainsman and in an article by Vance Johnson in the Amarillo Daily News

January 7, 1938. For eight years Old Blue proved so valuable in guiding the herds, that Goodnight refused to sell him. More than

ten thousand head followed the sound of Old Blue's bell north. Old Blue walked right into camp and eat bread, meat died apples and anything that the cook would give him.

He would sometimes bed down with the remuda. He understood the slightest motion of the point men. He was, according to Dobie, worth an extra dozen hands.

There were other lead steers belonging to other trail drivers. A lead steer called "Pardner" saved Bill

Blocker's life at the Salt Fork of the Arkansas. A lead steer named "John Chisum" led one of Jack Potter's herds

to safty in an 1889 blizzard in which thousands of cattle died. Of

eleven herds on the trail in the blizzard, only the one led by "John Chisum" got through.

A Blizzard on the Plains, F. W. Schultz, 1907.

Potter was the son of the famed

"Fighting Parson" Andrews Jackson Potter, a chaplain in the Confederate Army. Jack Potter named his

lead steers after famous people. Potter later explained:

Never in my life have I seen snowflakes as we made into. They were as big as your finger

and were driven by a gale blowing sixty miles an hour. We were going up El Muerto Creek,

and I kept wondering what traveling would be like when we left it and got out on the naked

divide.

By the time we reached the place to top out, the prairie was covered with snow.

The red sand-hill grass was a foot high here. I was piloting the herd, following

a newly beat-out road. It ;wasn’t graded or anything like that — just some twisting wagon ruts. The only way I could distinguish it was by noting that the snow was smooth in the ruts and uneven in the grass. I had to pull my hat down over my eyes to protect them from the cuutting storm. I could not see ten yards ahead, but I kept to the road. I had never been over it, and knew the country only in a general way.

"Then we came to a prong. I figgered one branch led off into the breaks of the

Pierdenal — towards shelter. I took it. But old John Chisum, close to my horse's tail,

refused to follow. He ducked into the one that seemed to keep on going over the bleak

prairie. I was puzzled and commenced to talk to that steer.

'You don't seem to realize I am piloting this herd,' I said

to him. 'I know a horse has more sense than a man. If you give

a horse with any sense at all his reins on a dark night or in a

snowstorm, he will take you to camp; but you've never been

where you are headed, so far as I know. What right has an old,

cold-blooded, scalawag steer to be making decisions for a trail

boss? If we don't find shelter before night, God knows what

will become of all of us. Nevertheless, I'm just guessing too, and

now I'm going to let you have your way.'

John Chisum was right. In twenty minutes we reached a ridge with canyons covered with big

pines running off on each side. The trail led down one of these into the Tremperos.

As we entered it, four riders from the ranch came out to help us pen and to welcome us to their shelter.

"The storm lulled for a few days, and we floundered on but if Clayton had been a mile farther off

I don't believe my horse would ever have got me there or that John Chisum would ever have

led the cattle into the shipping pens.* * * * There seemed to be only one John Chisum

on the trails that time —_but I do take a little credit to myself for having had sense enough

to pay attention to what a good lead steer says." As quoted by J. Frank Dobie, The Longhorns, p . 278-279

Potter's story, however, may be taken with a grain of salt. Potter contributed an article, "Coming up the Trail in 1882" for

Trail Drivers of Texas." The article has been repeated endlessly by various writers as if it were the Gospel Truth. In the article,

Potter recounted his misadventures at age 16 on his return to Texas from Wyoming and

the Crow Agency north of Sheridan. He had, he wrote, "never been on a railroad train, had never slept in a hotel, never taken a bath in a bath house."

Nevertheless, he was asked, he said, by George W. Saunders to help "Dog Face Smith" and his bunch from Cotulla in changing cars

down the line. "Old Dog Face and his bunch were pretty badly frightened and we had considerable difficulty in getting them aboard."

Potter continued:

Old Dog Face' was out of humor, and was the last to bed down. At about 3 o'clock our train was side tracked to. let the west-bound- t^ain pass.

This little stop caused the boys to sleetp the sounder. Just then the west-bound train sped by traveling at the rate of about forty miles an hour,

and just as it passed our coach the engineer blew the. whistle. Talk about your stampedes!

That bunch of sleeping cowboys arose as one man, and started on the run with

Old 'Dog Face' Smith in the lead. I was a little slow in getting up, but fell in with the drags.

I had not yet woke up, but thinking I was in a genuine cattle stempede, yelled out,

"Circle your leaders and keep up the drags." Just then the leaders circled and ran into the

drags, knocking some of us down. They circled again and the news butcher crawled out from under

foot and jumped through the window like a frog. Before they could circle back the next time,

the train crew pushed in the door and caught Old 'Dog Face' and soon the bunch quieted down.

The conductor was pretty angry and threatened to have us transferred to the freight department

and loaded in a stock car.

The story is no doubt a tweaking of the tail of George Saunders as well as the bunch down at

Cotulla, so much so that the editor of Trail Drivers found it necessary to include a disclaimer:

Editor's Note--The foregoing will be read with much interest by the old cowboys who worked the range and

traveled the trail with Jack Potter. Mr. Potter is now a prosperous stockman. owning large

ramch interests in Oklahoma and New Mexico. He is the son of Rev. Jack Potter, the

"Fighting Parson," who was known to all the early settlers of West Texas. The above artcile is characteristic of the humor and

wit of this rip-raring, hell-raising cow-puncher, who, George Saunders says, and other friends concur in the

assertion, was considered to the the most cheerful liar on the fact of the earth, But he was always the life of the

outfit in camp or on the trail.

Apparently, the point of the story was to make fun of Cotulla and the idea that tough Cotulla cowboys

were stampeded by the sound of a train. Hhowever, Cotulla cowboys were rough, so much so that allegedly when a train pulled into the Cotulla station, the

conductor would call out "Cotulla! Everybody get your guns ready."There were shootings on Front Street, Sheriff McKinney was murdered which resulted

in further gunfights. There were illegal hangings. The governor had to send in a troop of Texas Rangers.

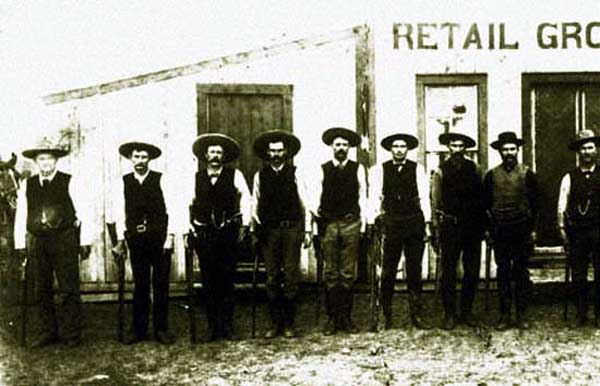

Texas Rangers in Cotulla, Texas, Feb. 1887.

A justice of the peace was killed in

a gunfight. The first courthouse was burned down -- arson. Indeed, the cowboys were allegedly fearless.

In an 1898 shootout at Pattershon's Saloon Henry May was shot and killed by

John Guy Smith. Smith was acquitted -- self defense. Smith was not, however,

Dog Face. Smith was involved in another shooting in the Burke Hotel and one time was shot in the back but survived.

An international incident occured when Mexican nationals.

were incarcerated in the local jail, removed, and lynched without going through the normal legal niceties.

Smith, who also went under the name

J. Guy Reed, left town about 1902 after being convicted several years before of criminal libel for writing in his paper the The LaSalle County Isonomy the following

billet doux concerning the town's founder, Joseph Cotulla:

“Scandal is a vulture that dips in dirty pools, by reason of which Joseph Cotulla,

Poland’s distinguished son, or at times not improperly denominated ‘La Salle’s Squaw

Belligerent,’ talks altogether too much with his mouth. It is a task of no inconsiderable

magnitude to convince the very easy-going Polack that his mouth was made as a means of

ingress for food, not for empty bombast. The highly-esteemed Joseph’s tongue is a little

too scurrilous. He should surprise it with a muzzle. The old fellow seems to be troubled with

an aggravated case of flatulency of the face. It often leaks like a lot of verba egesta.

Joseph, the atmospherical exponent of the liar’s inexorable decree, has had it in for the

editor for, lo, these many moons. (Meaning thereby that the said Joseph Cotulla had been guilty

of, and was in the habit of, making scandalous and scurrilous statements concerning others,

which, if true, would be disgraceful to him, the said Joseph Cotulla, as a member of society,

and the natural consequence of which is to bring him, the said Joseph Cotulla, into contempt

among honorable persons; and further meaning thereby that he, the said Joseph Cotulla, had the

moral vices of being a scandal monger and common liar, which, if true, would render him, the

said Joseph Cotulla, unfit for intercourse with respectable society, and such as would cause

him, the said Joseph Cotulla, to be generally avoided),” See Smith vs The State, 39 Texas Criminal Reports 326, 43 S.W. 1013, (1898)

Cotulla early worked for Ben Slaughter and was paid $7.00 a month in Confederate "blue backs."

After the Civil War he returned to Texas and built his herd by branding mavericks. Cotulla made two trips up the

trail in 1873 and 1874.

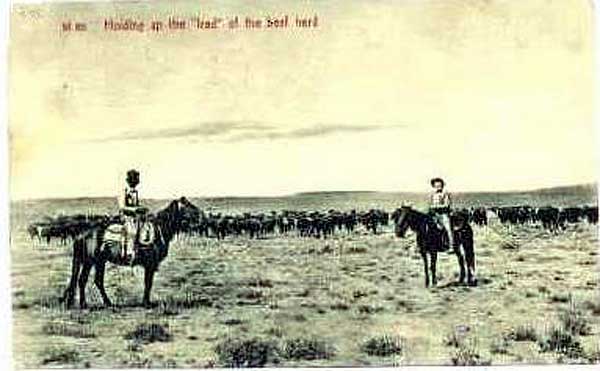

"Holding Up the Lead," undated

Ahead of the pointmen and the lead steer was the trail boss and ahead of him would be the

cook who would, among other things gather the occasional fuel, and set up for

the evening dinner. The cook was generally recognized as the second most

important man in the trail crew and would receive as much as $5.00 a month more than other drovers.

He was often experienced in all aspects of

trail work and could fill in where needed. Additionally, there were wranglers to tend to the horses. For each cowboy would

ride three or more horses in a day, so as to preclude horses from becoming winded.

Next Page, Cattle drives continued.

|