Guarding the Herd, Harper's Weekly, March 1878

At night the cattle would be bedded down near the camp. Two night riders would circle the herd

in opposite directions, so that on each circuit the two would each meet twice.

each circle.

. . . . . .

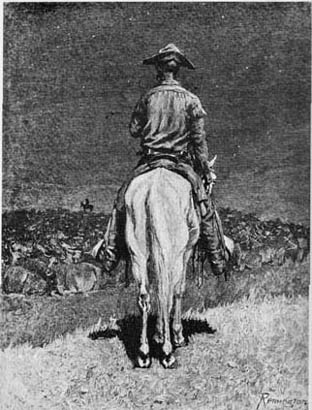

Left, "The Herd at Night," Frederic Remington, Century Magazine,

April 1888,

Right, Night Herding, engraving Scribner's Magazine, 1922, based on painting by

N. C. Wyeth But at night the dangers of a stampede might be worse. Ben Kinchlow recalled:

"Some evenin's you could see a little cloud risin' away up in the north an'

about dark you could see a little lightnin' danglin' an' then you better

look out 'cause that night you would sure hate trouble. On stormy nights

like that, I've seen balls of lightnin' danglin' all over the steers' horns

an' on them nights, they would almost be sure to run. We always kept some

of the cattle stirred up or awake at night 'cause a big herd of cattle will

run all night if they're tired an' get to sleepin' too sound. The least

racket will stampede 'em. You better never let 'em lay down an' go to sleep

an' get quiet; you'll have trouble sure as the world. The boys always sang

as they rode round the herd. That was the main thing, to keep a noise going

so that no sudden racket would stampede 'em. I used to 'odel' [yodel] aroun'

the cattle, but I never was much of a hand to sing. I could whistle an'

make all kinds of funny rackets. I could sing "Sam Bass' an' 'Bury Me Not

on the Lone Prairie,' but when all the hands could 'odel' it sho' was pretty

singin'".

Teddy Blue explained the effect of singing, "I know that if you wasn't singing, any little sound

in the night--it might just be a horse shaking himself--could make them leave the counry; but if you

were singing, they wouldn't notice it." Singing was common even if the cowboy couldn't sing. As observed by

J. Frank Dobie, "Many a waddie could no more carry a tune than he could carry a buffalo bull."

Stampede by Frederic Remington

Frederic Remington (1861-1909), was originally from upstate New York. In 1878, he was

sent to Yale and its newly established art school. At Yale he could not stand the

stuffy art curriculum, but was on the football team and was heavyweight

boxing champion. Upon his father's death he dropped out of college and shortly thereafter

took off for Montana. There he met an old freighter who, while sharing his coffee and

bacon with the young Remington, observed, "And now there is no more West." As a result,

Remington determined to document through his art the West that was. The first of

his works was accepted in Harper's Weekly in 1882. But by 1886, Remington was a success with

his art being featured on the cover of Harper's. Subsequently, he documented for the papers and

magazines the events of the day as well as the West. He was at Wounded Knee,

he convered the Spanish-American War in Cuba, but most of his art was drawn from a

studio in New York State to which he returned. Yet, even today, Remington is

regarded as a foremost documentor of the West that is now gone.

Roundup Wagon, approx. 1909.

Generally speaking because of movies such as Lonesome Dove, and Red River Valley, one

automatically pictures cattle trails such as the Texas Trail discussed below. Prior to the construction of the Oregon Short Line Railroad, discussed

with regard to Kemmerer, some of the greatest drives were from

eastern Oregon. The winter of 1880-1881 in eastern Oregon was particularly severe, depressing the price of cattle and

making it highly profitable to drive cattle to railheads in Wyoming and Nebraska.

In 1881, the Searight Cattle Company, owners of the Goose Egg (see N. Platte Valley),

drove some 18,000-20,000 head east to

Wyoming. The following year, an even greater drive was conducted by Lang and Ryan with

30,000 cattle, 120 cowboys, 800 horses, 40 wagons, 160 rifles, 30,000 rounds of

ammunition, and its own band.

Nor should it be taken that great cattle trails or epic cattle drives were limited to the American West. As discussed on a

subsequent page, such trails and epic drives also occurred in Australia and, indeed, in the Yukon.

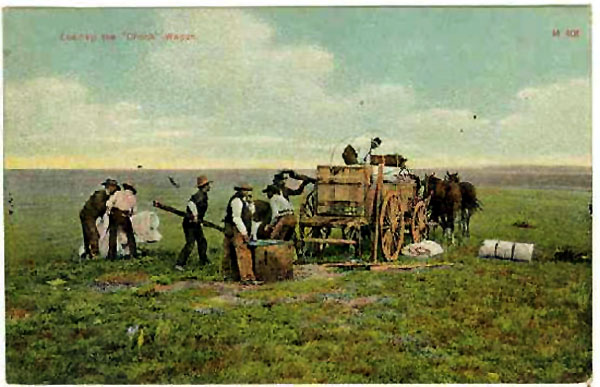

Loading the Chuck Wagon, 1909

In July of 1884, a severe epidemic of Texas fever appeared near Ogallala resulting in the

imposition of a quarantine of Texas cattle. To forestall the end of the industry,

Texas cattlemen and contract drovers sought the creation of a national cattle trail

from South Texas to the Canadian border. The proposed trail was to come up through

Eastern Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming and Montana. The bill died in the House

of Representatives. In 1888, direct rail connection from Fort Worth, Texas to

Orin Junctions southeast of Douglas was completed. Year old cattle could then be shipped directly from Texas to Orin Junction eliminating the need for

the great cattle drives of the 1870's and 1880's. In conjunction with the "Great Die-Off" discussed on a

subsequent page, the days of

the great cattle drives ended. Smaller drives from Orin Junction northward to Dakota Territory continued for a short time.

The trip northward by train was timed for the early spring grass in Wyoming so that the cattle

would regain weight as they moved northward to Powder River Country and the Belle Fourche.

Orin Junction, approx. 1917. Photo by The Revernd W. B. D. Gray and the Reverend Mrs. Gray.

Mrs. W. B. D. (Annette) Gray, was a correspondent for American Missionary Magazine. In the Magazine

she documented the travels of her husband and herself across Wyoming in support of the Congregational Church. Orin Junction, itself,

wasnamed for Orin Hughlitt, never amounted to much. Bill Barlow's Budget, in 1909 described the town

as consisting of one hotel, one store, and two saloons. One of the saloons belong to the infamous

Doc Middleton. The other belonged to John Henry Weaklen. The unloading of livestock was distinctly

seasonal and the herds moved out as soon as unloaded. As explained by Harry Arthur Gant, "The facilities in Orin were for

lots of cattle and not many people at one time. The usual procedure was for an otfit to

receive their herd and move out grazing." Gant: "I Saw Them Ride Away," p. 56.

The hotel left much to be desired. When Gant arrived in

Orin Junction there was a cold rain and the hotel was full. He had to share a bed with a

stranger. In order to save having to purchase land for the hotel,

it was constructed partially in the street and partially on railroad right-of-way. In this manner The propriator did not

have to pay for the land or pay taxes on the real estate. He was hoping

to claim the property by adverse possession. Ultimaely the railroad noticed.

See Bolln vs. Colorado & S. Ry. Co., 23 Wyo. 395, 152 Pac 487 (1915).

Texas Trail Monument Near Lusk, see text below.

Depicted on the above monument are many of the famous brands of the outfits that trailed cattle from

Texas to Montana. For identification and explanation of brands see Brands.

A similar monument will be found at Pine Bluff through which the trail passed. One of the more interesting memorials to the

Texas Trail, lies out on the lonely rolling plains of the Thunder Basin National Grassland of western

Weston County, on State Road

450 east of Wright. It is a small wooden marker affixed to a barbed wire fence noting the Texas Trail.

Texas Trail Marker, Highway 450, Thunder Basin National Grassland. Photo by Geoff Dobson, 2013.

The sign reads, "GUS

McCRAY

WAS

HERE

(TEXAS TRAIL

1867-1891)"

Gus McCrae was one of the central characters in the novel and movie "Lonesome Dove." The character was modelled

after Oliver Loving who with Charles Goodnight is regarded as a father of the Texas Trail.

Loving died of gangrene following a fight with Indians. He never, unlike the movie character,

made it to Montana but died at Fort Sumner. His body was returned to Texas by his partner Goodnight.

Nearby is a more formal marker under the heading "TEXAS TRAIL, 1866-1897."

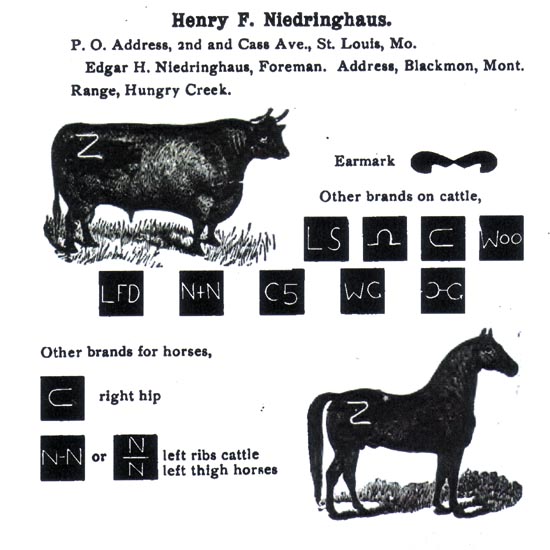

The last of the great trail drives along the Texas Trail was by the N Bar N in 1892 when 25,000 head were moved

from the Ranch's Texas operation headquartered in Panhandle City, Texas to its main holdings in

Montana, and the following year when 40,000 cattle were moved. The drive took 5 months. It has been estimated in the final two years of

trailing cattle, half of the herds on the Texas Trail were those of the N Bar N. The N Bar N was

started in 1886 by William F. Niedringhaus and Frederick W. Niedringhaus. The winter of 1886-1887 devastated the company's

Montana Herds. The brothers recapitalized at $1,000,000 and built the herds back up in Texas and then drove them to their Montana range. Its operations

required fifteen chuck wagons.

N Bar N Cowboys and Wagons.

By 1899, The N Bar N had fairly well closed its operations in Montana. Today, the N Bar N

is remembered as having been the home of Charles Marion Russell for several years.

N Bar N Brands.

In 1893, the

Matador's last drive started out on May 25, 1893 from White Deer, Texas. In July, the

Matador herd reached Wyoming and a month later Dakota. The Matador was the last of the great

British-owned cattle companies. In 1951, the Matador was liquidated, a victim not of weather, homesteading, or Texas fever, but,

instead, of ruinous post-war taxes. First, the company paid American taxes, then it paid British corporate taxes, 9 shillings on every pound, and

finally the shareholders paid taxes upon the earnings left over and distributed as dividends. Thus, the goose was

slain.

Another branch of the Texas Trail ran through Colorado to Pine Bluffs and from there it passed Albin, Lagrange, east of

Yoder, between Torrington and Lingle, and up to Lusk. A museum devoted to the trail is located

at Pine Bluffs. Thus, with the passing of the great cattle drives, emphasis on the western plains passed

to the routine of the Spring Roundup, the Fall Roundup, and branding. Shorter drives to

local railheads continued, but hurrahing of towns at the end of months-long drives were a thing of the

past.

Background music this page: Riders in the Sky as played by Duane Eddy.

Riders in the Sky

An old cowboy went riding out one dark and windy day

Upon a ridge he rested as he went along his way

When all at once a mighty herd of red eyed cows he saw

A-plowing through the ragged sky and up the cloudy draw

Yippie yi Ohhhhh

Yippie yi yaaaaay

Ghost Herd in the sky

Their brands were still on fire and their hooves were made of steel

Their horns were black and shiny and their hot breath he could feel

A bolt of fear went through him as they thundered through the sky

For he saw the Riders coming hard and he heard their mournful cry

Yippie yi Ohhhhh

Yippie yi yaaaaay

Ghost Riders in the sky

Their faces gaunt, their eyes were blurred, their shirts all soaked with sweat

He's riding hard to catch that herd, but he ain't caught 'em yet

'Cause they've got to ride forever on that range up in the sky

On horses snorting fire as they ride on hear their cry

Yippie yi Ohhhhh

Yippie yi yaaaaay

Ghost Riders in the sky

As the riders loped on by him he heard one call his name

If you want to save your soul from Hell a-riding on our range

Then cowboy change your ways today or with us you will ride

Trying to catch the Devil's herd, across these endless skies

Yippie yi Ohhhhh

Yippie yi Yaaaaay

Ghost Riders in the sky

Ghost Riders in the sky

Ghost Riders in the sky

Devil's Herd in the Sky.

The song was written in 1948 by Stan Jones based on a legend told to him as a youth by an old

Arizona cowboy. Numerous recordings of it have been made including ones by the Sons of the Pioneers,

Vaughn Monroe, and Johnny Cash. A parody entitled Rafael in Isanbul is sung by Liverpool fans.

Next Page, Roundups.

|