Swimming the Platte, portion of engraving by E. Boyd Smith.

As indicated on the previous page, the dangers of the trail were not limited to stampedes.

Many were killed at the very beginning of

the drive at the Red River. There were four crossings: Rock Rock River Crossing, Red River Station, Doan's Crossing, and

Ringgold. Rock River Crossing on the Shawnee Trail at the confluence of the Red River and the Washita fell into disuse

for cattle as the trails moved westward.

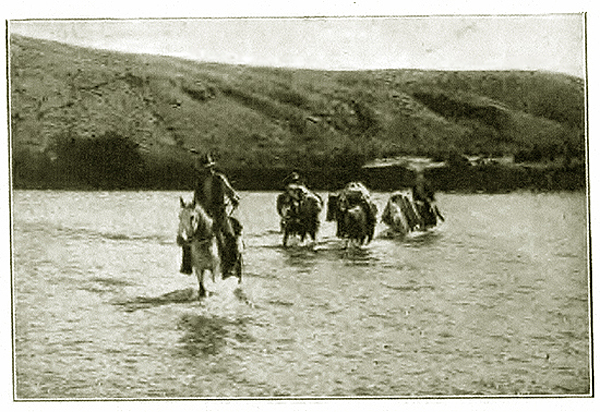

Trail Outfit at Rocky Bluffs Ford of the Red River

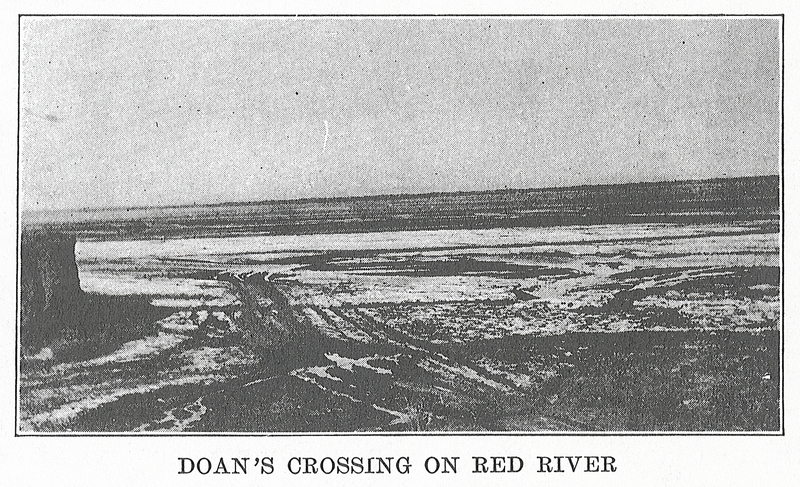

Andy Adams described Doan's Crossing:

"Red River, this boundary river on the northern border of Texas, was a terror to trail drivers.

The majestic grandeur of the river was apparent on every hand, with its

red bluff banks, the sediment of its red waters marking the timber along

its course, while the driftwood, lodged in trees and high on the banks,

indicated what might be expected when she became sportive or angry.

The crossing had been in use only a year or two when we forded, yet five

graves, one of which was less than ten days made, attested her disregard

for human life. It can safely be asserted that at this and lower trail

crossings on Red River, the lives of more trail men were lost by drowning

than on all other rivers together."

Doan's Crossing of the Red River

Doan's Crossing was the last site of civilization before heading into Indian Territory. It was the location

of a store and post office established by Corwin F. Doan (1848-1929) and his uncle Jonathan Doan. The store was establshed in

1878 and the Post Office in 1879. C. F. Doan later described that the first sign

that the trail herds were beginning to arrive, one of Ab Blocker's colored hands brought in mail.

In Trail Drivers of Texas, compliled and edited by J. Marvin Hunter, C. F. Doan described his

establishment:

The first house at Doan's was made of pickets with a dirt roof and floor of the same material.

The first winter we had no door but a buffalo robe did service against the northers.

The store which had consisted mainly of ammunition and a few groceries occupied one end and the

family lived in the other. A huge fireplace around which Indians, buffalo hunters and the family sat, proved very comforting.

The warmest seat was reserved for the one who held the baby and this proved to be a very

much coveted job. Furniture made with an ax and a saw adorned the humble dwelling.

Original store at Doan's Crossing.

Doan continued in his description:

Later the store and dwelling were divorced. An

adobe store which gave way to a frame building was built. Two log cabins for the

families were erected. In 1881 our present home was built, the year the county

was organized. This dwelling I still occupy. Governors, English Lords, bankers,

lawyers, tramps and people from every walk in life have found sanctuary within its

walls. And if these walls could speak many a tale of border warfare would echo from i

ts gray shadows.

Doan's Store, 1870's.

Besides being the end of civilization before entering Indian Territory, the crossing was where state inspectors examined the cattle for

compliance with Article 777 of the 1879 Texas Revised Civil and Criminal Statutes. The statutes made it a

criminal offence to drive cattle out of the state without the cattle having a road brand and without having the

cattle inspected. On one occasion, about 14 herds were being driven northward by the Butlers. Two of the state inspectors found two

bovines which had no brands. They threatened Mr. Butler with fines of $50.00 each. Dollars would be about equal to two months pay for a cowboy.

.Butler solved the problem by having the cowboys kidnap the inspectors and take them almost

deep into Indian Territory almost to the Kansas border near the Arkansas River. The inspectors then had to walk and swim back to Texas.

The Butlers were not bothered again.

As the herds proceeded through Indian Territory they ran a guantlet. Most of the Indians could be placated by the gift of

one or two sickly steers. As previously noted, it was customary to pick up strays along the way and retain them. An exception

existed when the stray belonged to a trail herd that was up ahead. Under those circumstances there was indeed honor amongst the thieves. The stray joined the

herd until the preceeding herd

was overtaken. The stray would then be returned to its rightful owner. W. T. "Bill" Jackman (1852-1937) drove herds north for some eleven years. In his first drive as

a trail boss for the Adams Brothers, he was told to gather up "everthing you find regardless of brand." He did so and after finding out that another trail boss was in the jail at

Bandera for the same thing, kept to "high places" near the herd to avoid keeping his fellow trail boss company.

One year, Bill's herd picked up a stray belonging to one of Ike Pryor herd's. Ike (1852-1937) was a well known and respected Texas cattleman.

At age 5 Ike had been orphaned and was on his

own at age 9 selling newspapers to the Union Army of the Cumberland. After the war, Ike started out as a $15.00 a month cowboy. By 1881, Ike was trailing

45,000 head northward. In 1917 in Cheyenne, Ike was elected as President of the American National

Live Stock Association. He was re-elected by acclamation.

Bill Jackman took Ike's stray with all good intentions of returning the animal when he caught up with Ike's herd. Red River was crossed. Bill proceeded

northward into Indian Territory.

One afternoon, a band of about forty Indian warriors including their squaws, rode up to Bill's herd. The chief handed Bill a letter:

" To the trail bosses:

"This man is a good Indian; I know him personally.

Treat him well, give him a beef

and you will have no trouble in driving through

his country."

S/ IKE T. PRYOR."

After reading the letter, Bill rode into the herd, cut out Ike's steer and presented the animial to the chief.

The Indians killed the steer and

had a big feast. Bill went on North with his herd undisturbed by the Indians, thanking Ike for the good advice.

River Crossing, Alfred R. Waud, Harper's 1867

For information as to Alfred R. Waud, see Yellowstone.

Monument at Doan's Crossing

Monument at Doan's Crossing

Today, the crossing at Red River Station is on privately owned land and is not

accessible. Instead, the visitor may gaze upon a monument and a wheat field, but the

river is not to be seen. At Doan's Crossing there is C. F. Doan's adobe house along

with another monument bearing

the brands of many of the outfits passing by.

Addison Spaugh, later a foreman for the Converse Cattle Company when it was located on

Old Woman Creek north of Manville, later observed:

Outfits had gaily started north, only to reach their destinations months later with

half their cattle gone, some of their men laying in shallow graves along the trail, or

lost in the waters of angry rushing rivers.

Besides the danger of drowning, the river bottoms were often quicksand. E. E. Smith,

"The Passing of the Cattle-Trail," X Transactions of the

Kansas State Historical Society, 1907-1908, described

an 1880 cattle drive undertaken for Robert A. Harper:

When

the Canadian river was reached it was bank full and still rising, and constant rains kept

it up for several days. Each day while thus kept waiting outfits were constantly arriving,

till at last, worn out with the delay, the managers of the several cattle and horse herds

held a council, which resulted in a decision to force a passage. This was very dangerous,

for the Canadian was full of quicksand, and, like the Cimarron, "buries its dead." Rafts

were made, camp-equipage, wagons, etc., were crossed safely over. Following this the herds

were rounded up with men in position, and a small bunch of 500 head of cattle was driven

into the river, for cattle will take water more readily than horses and swim better.

The cattle served to set the quicksands in motion and to lead the horses across. Some of

the men swam their horses to guide their cattle and keep them moving to the farther shore.

The horses were put into the river immediately behind the cattle, and crossed with the loss

of five head. While crossing another bunch of cattle, a few got upon a sand-bar and began

"milling" (moving around in a circle). and several head were drowned before the "mill"

could be broken up. A number of Indians who were watching at once fell to rescuing carcasses,

and succeeded in getting four or five out of the water, when they at once proceeded to have a

feast.

W. B. Foster described his efforts at breaking up milling in the middle of the stream. The cattle were jammed together so in

Foster's words, "that it was like walking on a raft of logs." He stripped to his underwear, got off his horse and onto the cattle and mounted the only large steer and got him

to the shore and then drifted down stream to his horse. He then had to spend the entire day tending to the

herd in his underwear without saddle or hat until his mess mates could catch up about sundown.

One method of avoiding drowning

on a river crossing was to unsaddle one's horse and to ride across naked. In that manner, one would

not be weighed down by clothing, boots, and gear.

Cimarron River Crossing

Billy Dixon commented as to the Cimarron:

The Cimarron is commonly regarded as one of the most dangerous streams in the

southwest. Its width often is three or four hundred yards. If there were no sand,

the stream would be rather imposing in size. It is filled to the brim with sand,

however, and through the sand is an underflow. The quicksands of the Cimarron are

notorious. No crossing is ever permanently safe. The sand grips like a vise, and the

river sucks down and buries all that it touches—trees, wagons, horses, cattle and

men alike, if the latter should be too weak to extricate themselves. In the old days

countless buffaloes bogged down and disappeared beneath the sands of the Cimarron.

Their dismembered skeletons are frequently uncovered at this day when the river is

in flood.

After a rise, the Cimarron is peculiarly dangerous. As it boils and rolls

along, the river loosens and hurls forward an astonishing quantity of sand. Unless

naked a man quickly finds himself pulled down by the increasing weight of sand that

lodges in his clothes, and swimming becomes difficult, and finally impossible, save

without tremendous exertion. Stripped bare, a swimmer can sustain himself in the

Cimarron with greater ease than in most other streams, as the salt and sand give

the water extraordinary buoyancy. No man should ever tackle the Cimarron in flood

until after he has stripped to the skin and kicked off his boots. The experienced

cow-pony seems to realize its danger when crossing the Cimarron, taking short,

quick steps, and moving forward without the slightest pause. To stop would be to

sink in the quicksand.

Teddy Blue Abbott stripped to cross the Yellowstone. Abbott recalled that one of his messmates asked, "What are you taking your clothes off for? Hell, it's nothing but a crick."

Another did not want to take off his boots, but Abbott told him by the time he got to the otherside he

would think it was the Atlantic Ocean.

Sometimes riding across naked could cause unforeseen difficulties. Jeremah Milton "Jerry" Nance (1850-1926),

an early Texas drover recalled an

incident on the Canadian. The herd had reached the river which was on the rise. Other herds were arriving. Fearing that the various herds

would nix, it was decided to cross the river. The entire trail crew stripped in peparation.

The cattle were started across and were going fine, when it came up a terrific hailstorm,

which interrupted the proceedings. One man was across on the other side of the river, naked,

with his horse and saddle and about half of the herd and the balance of us were on this side

with the other half of the herd and all the supplies. There was no timber on our side of the

river, and when the hail began pelting the boys and myself made a break for the wagon for

shelter. We were all naked, and the hail came down so furiously that within a short time it

was about two inches deep on the ground. It must have hailed considerably up the river, for

the water was so cold we could not get any more of the herd across that day. We were much

concerned about getting help to the man across the river. We tried all evening to get one of

the boys over, to carry the fellow some clothes and help look after the cattle, but failed in

each attempt. We could not see him nor the cattle on account of the heavy timber on the other

side, and the whole bottom was covered with water so that it was impossible for him to come

near enough to hear us when we called him. The water was so cold that horse nor man could

endure it, and in trying to cross over several of them came near drowning and were forced to

turn back, so the man on the other side had to stay over there all night alone and naked.

Nance was estimated to have trailed some 200,000 head north. One of his first drives was a three month drive to Cheyenne.

Samuel Dunn Houston, a

cowboy who rode for Tom Moore, a contract drover, recalled of an 1879 trail drive:

When we reached Fort Laramie we made ready to cross. I pulled my saddle off and then my clothes.

Tom came up and said, "Sam you are doing the right thing." I told him I had crossed

the river before and that I had a good friend who once started to cross the

river and he was lost in the quicksand. His name was Theodore Luce of Lockhart, Texas.

He was lost just above the old Seven Crook Ranch above Ogallala.

And Andy Adams similarly described in his The Log of a Cowboy a young cowboy who drowned crossing the

North Platte near Fort Laramie. In his pocket was found a letter from his mother bidding him

to take care. His two brothers had drowned on the trail. A minister from a nearby emigrants' train delivered a

service. Thus, a young lad far from his home in Texas was laid to rest beside the Platte while the

minister's two daughters sang How Firm a Foundation, the same hymn as sung at the funeral

of General Lee. The third verse:

When thro' the deep waters I call thee to go

The rivers of woe shall not thee overflow

For I will be with thee, thy troubles to bless

And sanctify to thee thy deepest distress

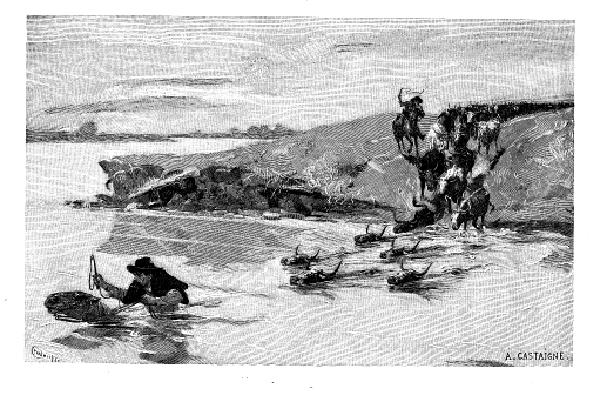

River Crossing, Jean Andre Castaigne, Scribner's Magazine

J. A. Castaigne (1861-1929) was a French artist who provided art work

in the 1890's for American periodicals, Scribner's, Century Magazine,

Harper's, and McClure's. He is sometimes listed as a Western artist, mainly

due to drawings of American Indians. He was a recipient of

Legion d' Honneur.

Music this page:

Red River Valley

From this valley they say you are going.

I will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile.

For they say you are taking the sunshine.

That has brightened our pathway awhile.

Chorus:

Come and sit by my side if you love me.

Do not hasten to bid me adieu.

But remember the Red River Valley

and the cowboy that loves you so true.

From this valley they say your are going.

I will miss your sweet face and your smile.

Just because you are weary and tired,

You are changing your range for awhile.

Repeat Chorus

I've been waiting a long time my darling

For the sweet words you never say.

Now at last all my fond hopes have vanished.

For they say you are going away.

Repeat Chorus

O there never could be such a longing

In the heart of a poor cowboy's breast.

That now dwell in the heart you are breaking.

As I wait in my home in the west.

Repeat chorus

Do you think of the valley you're leaving?

O how lonely and drear it will be!

Do you think of the kind heart you're breaking.

And the pain you are causing to me?

Repeat Chorus

As you go to your home by the ocean,

May you never forget those sweet hours

That we spent in the Red River Valley,

And the love we exchanged mid the flowers.

|

The origins of "Red River Valley" are uncertain. It has been variously traced to

the Prairie Provences of Canada and to Iowa. Various valleys have been used in the words,

Sherman Valley, Mohawk Valley, as well as the Red River. It is uncertain whether it

originally referenced the Red River of the North or the Red River that the cowboys crossed

on the way to the north along the cattle trails to Wyoming and Montana. It has even found its way

across the Pond where the melody is used in the traditional Liverpudlian song by those that wear a

red and white liver bird upon their chests,

Poor Scouser Tommy [Use browser "back" button to return]:

Let me tell you the story of a poor boy

Who was sent far away from his home

To fight for his king and his country

And also the old folks back home

Now they put him in a Highland division

Sent him off to a far foreign land

Where the flies flew around in their thousands

And there's nothing to see but the sand

Well the battle started next morning

Under the Libyan sun

I remember that poor Scouser Tommy

Who was shot by an old nazi gun

As he lay on the battle field dying (dying dying)

With blood gushing out of his head

As he lay on the battle field dying (dying dying)

These were the last words he said...

[Remaining verses sung to the tune of "The Sash My Father Wore."]

Ohhhhhh... I am a Liverpudlian

I come from the Spion Kop

I love to sing, I love to shout

I go there quite a lot (Every Week)

We support the team thats dressed in Red

A team that you all know

A team that we call Liverpool

And to glory we will go

We've won the League, we've won the Cup

And we've been to Europe too

We played the toffees for a laugh

And we left them feeling blue - Five Nil!

|

Writer's note: "Spion Kop" refers to the steep stands behind the goal occupied by the most

vociferous Liverpudlians. They are so called because of

the stands supposed resemblance to a hill which was the site of a Boer victory near Ladysmith, Natal, South Africa,

during the Boer Wars. The Toffees, Everton Football Club, a main rival of Liverpool F.C. There is a pun in the last

line, Everton are the "Blues." The liver bird, pronounced "Ly-ver," a bird that perches high on top of the Liver Building and is the

symbol of the Liverpool Football Club.

Next Page, Cattle drives continued.

|