|

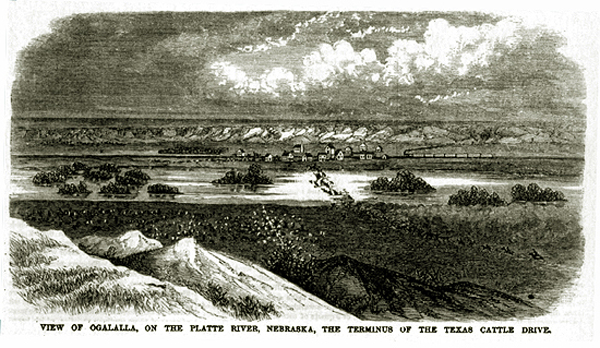

Ogallala, Nebraska, 1878.

Initially, the cattle trails ran

north to railheads in Kansas, but, as the eastern plains were taken over by farmers and

barbed wire and the scourge of Texas fever, the trails moved westward. The end of the trail towns such as Caldwell, Kansas, Hunnewell, Kansas, Ogallala, Nebraska, and

Billings, Montana, and their saloons and dance halls were a tad rough. One resident of Caldwell complained of the Red Light Saloon:

The scenes there presented reminded me of the early times in Cheyenne, when

murder ran riot and the pistol was the only argument.

Outside of Caldwell was a

hill where damsels of the evening would maintain a lookout for the trail herds coming toward town. Thus with warning,

the saloons and girls could get ready for the expected rush of business. Caldwell in its

first three years went through nine town marshals, several having met their Maker near

the saloon. On June 22, 1882, the town's tenth marshal was

killed in the Red Light Saloon. With the killing of Marshal George S. Brown, Caldwell had enough of the saloon. The proprietor and

proprietress of the saloon, George and Maggie Wood, found it expedient to leave town.

As the town residents were bidding the Woods farewell, the saloon mysteriously caught fire and burned down.

Dance Hall scene, Billings, Montana, approx. 1887.

Hunnewell, with one hotel, two stores, a barbershop, eight or nine saloons and a couple of dance halls also

provided entertainment. The cowboys would ride their horses into the saloons. Sometimes they would take the

barrels of sugar from the stores to feed their horses. When the cowboys were in town, lights on the

trains would be extinquished lest they be used for target practice. The most famous of the gunfights in

Hunnewell was on October 5, 1884, when one cowboy and a deputy sheriff were killed in Hanley's Saloon. No one was

charged.

The Texas Trail was

the last of the great trails, with the last drives in the 1890's. The Texas Trail, originally blazed by John Lytle in 1874, was not a

clearly defined road or path, in the sense, say, of I-25. Originally, it was some

twenty miles wide, running from Red River northward, with various branches, all

ultimately leading to Ogallala, in the words of Andy Adams, the

"Gomorrah" of the cattle trails. Indeed, Ogallala was so bad that

at least one cattle company which on drives would allow its boys the freedom of

Dodge City, declared it off limits, thus giving the town the reputation of being

"too tough for Texans." Indeed, the owner of one hotel told an eastern

visitor that there was only one woman in town, the hotel owner's wife, all the others

were "ladies." The "ladies" would usually be brought in from Omaha for the "season."

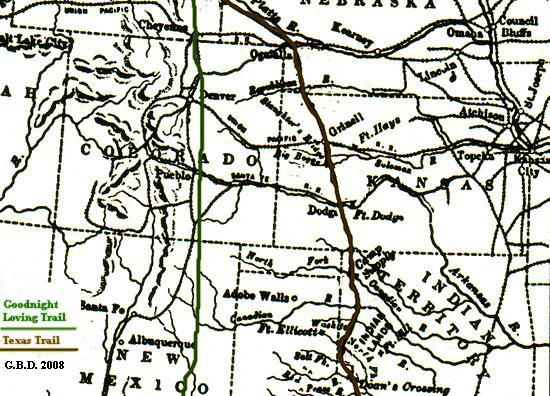

Texas Trail, Ogallala to Fort Benton

Texas Trail, Doan's Crossing to Ogallala; Goodnight-Loving Trail, New Mexico to Cheyenne, 1882

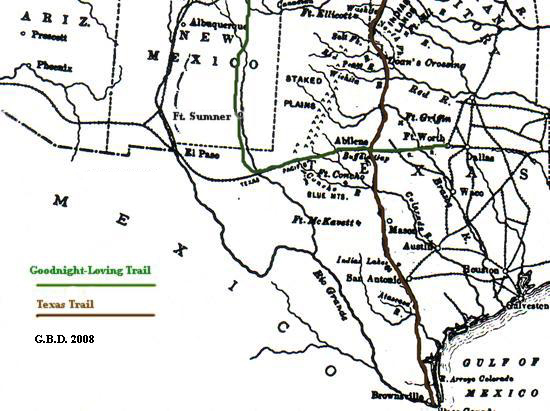

Texas Trail, Brownsville to Doan's Crossing; Goodnight-Loving Trail

Ft. Worth to the Cimmeron, 1882

Wyoming Stockgrower, Edgar Beecher Bronson, trailed 1500 cattle to

Ogallala in 1882 and in his 1908 Reminiscenses of a Ranchman described the town at the height of the

season:

A wonderful sight was the Platte Valley about

Ogallala in those days, for it was the northern

terminus of the great Texas trail of the late '

70s and early '80s, where trail-drivers brought

their herds to sell and northern ranchmen came to

bargain.

That day, far as the eye could see up, down, and

across the broad, level valley were cattle by the thousand—

thirty or forty thousand at least—a dozen or

more separate outfits, grazing in loose, open order

so near each other that, at a distance, the valley

appeared carpeted with a vast Persian rug of intricate

design and infinite variety of colours.

Approached nearer, where individual riders and

cattle began to take form, it was a topsy-turvy

scene I looked down upon.

Ogallala, Nebraska, undated

The town itself consisted of

The one store and the score of saloons, dance halls, and gambling joints that lined up south of

the railway track and formed the only street Ogallala could boast, were packed with wild and woolly,

long-haired and bearded, rent and dusty, lusting and

thirsty, red-sashed brush-splitters in from the trail

outfits for a frolic.

And every now and then a chorus of wild, shrill

yells and a fusillade of shots rent the air that would

make a tenderfoot think a battle-royal was on.

But there was nothing serious doing, then; it was

only cowboy frolic.

One of the principle saloons was Jim Tucker's Cowboy's Rest. Inside

was

a rude pine "bar" on

the right invited the thirsty; on the left, noisy "

tin horns," whirring wheels, clicking faro " cases,"

and rattling chips lured the gamblers; while away

to the rear of the room stretched a hundred feet

or more of dance-hall, on each of whose rough

benches sat enthroned a temptress—hard of eye,

deep-lined of face, decked with cheap gauds, sad

wrecks of the sea of vice here lurching and tossing

for a time.

* * * *

The room was packed: a solid line of men and

women before the bar, every table the centre of a

crowding group of players, the dance-hall floor and

benches jam-full of a roystering, noisy throng.

At the moment all were happy and peace reigned.

But there was one obvious source of discord—

there were " not enough gals to go round"; not

enough, indeed, if those present had been multiplied

by ten, a situation certain to stir jealousies and

strife among a lot of wild nomads for whom this

was the first chance in four months to gaze into

a woman's eyes.

And while Bronson was standing in the corner having just been introduced to

a Miss De Puyster, Bill Thompson, brother of the infamous shootist Ben Thompson, popped in

the door and did a quick shot at proprietor, Jim Tucker. Tucker fell.

Thinking Tucker dead, Thompson turned to leave. But Tucker was not dead. Only three of his fingers

had been shot off. Tucker coming to, grabbed a shotgun, followed Thompson out the door, and

levelled the gun across the stump

of his maimed left hand, and emptied into Bill's

back, at about six paces, a trifle more No. 4 duck-

shot than his system could assimilate.

The festivities were only briefly interrupted. Bronson continued:

erhaps altogether ten minutes were

wasted on this incident and the time taken to tourniquet and

tie up Jim's wound and to pack Bill inside and

stow him in a corner behind the faro lookout's chair,

and then Jim's understudy called, " Pardners fo' th'

next dance! " the fiddlers bravely tackled but soon

got hopelessly beyond their depth in "The Blue

Danube," and dancing and frolic were resumed, with "Miss De Puyster"

still the belle of the ball.

Nebraska cattleman, John Bratt, whose home ranch was near North Platte, also had remembrances of Tucker's

saloon. He recalled that cowboys would ride into the establishment and jump their horses on to the pool and billiard tables. Some,

who were crack shots would shoot the glass out of a man's hand while it was up to his mounth or see how close they could shoot off a

cigar in a man's mouth without grazing his nose with a bullet. See Bratt, John:

Trails of Yesterday, The University Publishing Company, Lincoln, 1921.

Bratt described Ogallala as: a wide-awake, wild, and sometimes wicked town. For many years it was the distributing point of the

Texas cattle, but later owners began to bring up their own herds to sell to the

Northern cattle growers. I have many times seen as many as fifty thousand cattle ranging,

being held in different herds along the bottom and foothills on the south side of the South

Platte River, strung along from ten to fifteen miles east, west and south of Ogallala.

Ogallala had its numerous saloons, dance houses and gambling dens, all running in full

blast both night and day. The town marshal was a brave fellow, but there were times when he

went to cover, being unable to control the bad ones, not a few of whom had to be killed.

Grant Shumway put it differentlly. Being marshal of Ogallala "required nerve and good judgment."

Bratt recalled that one night, the cowboys got into a fight in the saloon. After completing the wrecking of the saloon, they

piled out into the darkness of the street. The only light was the faint glow from one of the windows of

the Leach House hotel. The light was cast by a solitary oil lamp sitting on

a wash stand. About 15 shots came through the window, smashing the oil lamp. Within the room at the time

were some of the leading cattle barons including one of the Bosler Brothers all scrambling to exit the

chamber. Bratt marveled that no one was wounded, killed, or why the hotel did not burn down.

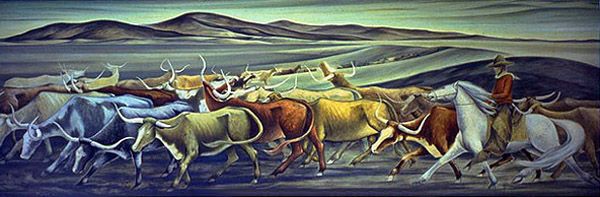

The Great Texas Trail ended in the 1890's. Few reminders of Ogallala's notorious past remain. One is the Works Progress

Administration mural in the post office.

Mural in Ogallala Post Office.

Caldwell and Ogallala were not the only places where there were resorts to tempt trail drivers.

In 1892, Harry Arthur Gant night hawked on a drive for the C Y from Casper to

the Company's northern ranges in Dakota Territory. He recalled in his "I Saw Them Ride Away," Castle Knob Publishing, 2009, p. 72,

that as the drovers approached the Belle Fourche they came across "cat wagons." The ladies within

would set up their wagons near where the trail would pass. When trail driving season was over,

the ladies would move close to sheep shearing camps and later to hay camps before winter would set in.

From Ogallala the trails split off. One followed the Platte to Fort Laramie and westwardly

to provide cattle for the Fort Washakie and Crow agencies in Wyoming. Another

crossed the Niabrara River and ultimatly connected to the Cheyenne River. From there it

headed northward to Powder River and up to Miles City. Other branches went through Pine Bluffs and northward past Lusk. One branch

reached northward into Saskatchewan.

Next Page: Texas Trail continued, Powder River Country.

|