|

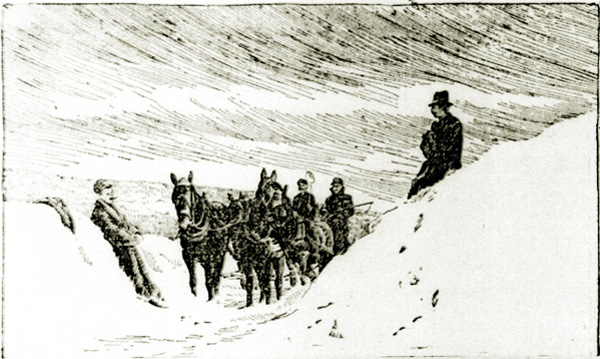

Winter Crossing of Teton Pass approx. 1895

If Jackson was isolated during the summers, access to the valley at the turn of the Twentieth Century in the winter

was almost impossible. Writer Frederick Ireland, "The Wyoming Game Stronghold," Scribner's Magazine, Sept. 1903, described

his trek into the valley:

The valley between the Wind River and the Tetons is cut off from the rest of the

world for more than six months each year, except to those willing to follow the mail carrier who pilots a pack-horse over the

Teton Pass. I spent nearly a month trying to find a way to cross the Shoshone Mountains before the first of June, but the guides

who lived in that country finally gave it up, and I had to go back to Rawlins and around by the railroad to St. Anthony in

Idaho, a distance of eight hundred miles, before I could get where I wanted to go, to see the

winter assemblage of the wapiti.

* * * *

The stage stops at the foot of the Teton Pass, so you must hire a saddle-horse from the local liveryman, and be responsible for your own safekeeping thereafter.

The mail carrier goes on horseback, and if you wish you follow his track in the snow. At first there is a road that is not hard to follow;

but when you have climbed half way up the valley you find nothing except a single horse track,

beaten down after each storm, with snow ten feet deep in either side. If the horse steps off the narrow trail he flounders neck deep. The mail

carrier sends the pack-horse ahead of him, and so is warned where the soft places are. When the snow is melting in the spring, the water cuts holes

beneath the surface, so there are hidden caves and pitfalls into which the horse sometimes falls out of sight. If you keep discreetly in the

rear you will get plenty of entertainment watching the horse and the boy ahead of you; and if they succeed in weakening the snow

so that your own horse takes an unexpected plunge, you will have some amusement on your own account.

Indeed, the local Forest Reserve Supervisor, Robert Miller reported in Febrary 1903 that he had attempted on Jan. 22 to traverse the pass, but was only able to reach

Louis Lockwood's Road Ranch a mile and a half west of Wilson and had to turn back. There, the snow was 4 1/2 feet deep. Further up the pass at Scott's the

snow was seven feet deep. In six days only one mail had gotten through.

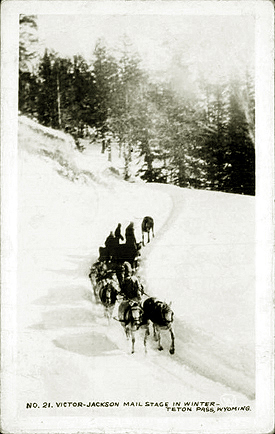

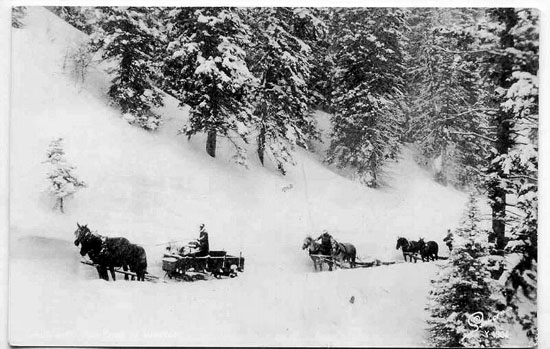

Winter Stage from Jackson to Victor, Idaho, undated.

Photo by Charles Wesley Andrews.

As late as the early 1920's, the United States Mail was delivered by

stage coach rather than by motor truck. In 1920, Wayne Ricks who had the contract for hauling the mail purchased

a new International Truck in Salt Lake City. Unfortunately, it required two teams of horses to

assist the truck in making it over the summit. In the winter passage in and out of

the valley was by means of a horse-drawn sleigh.

Winter Stage from Jackson, Wyoming to Victor, Idaho, undated.

Photo by Charles Wesley Andrews.

The passage over the pass by sleigh was also fraught

with the danger of avalanches. In 1913, mail carrier Owen Curtis was killed in the Pass by an

avalanche. The following year, another mail carrier Frankie Parsons lost his life to the

"white death." On February 11, 1932, 20-year old William "Merl" Swanson was driving the mail sleigh across Teton Pass toward

Jackson. In the sleigh, in addition to Swanson, were ten passengers. The sleigh was about to enter Boulder Gulch, a notorious

avalanche area, when One of the horses stopped and refused to proceed. As Swanson was arguing with the horse, an avalanche swept in front of

the mail sleigh. Thus, as noted by the Jackson Courier, the balky horse saved eleven lives. On the same day,

Swanson's father Lorenzo Swanson, his 17-year old brother Harry Buford Swanson, and 23-year old brother Lars were cutting

wood near Crater Lake at the base of the "Glory Hole," another infamous slide area. Harry was not so lucky. There, another avalanche carried the younger brother to his death. Harry's body was not found until

May. The avalanche at Boulder Gulch carried away the telephone line to Jackson. News of the

fatality and the narrow escape of the mail sleigh passengers had to be routed via Driggs, Pocatello, Rock Springs, Lander and Twogwotee Pass to Jackson. Notwithstanding,

his brother's death, Merl delivered the mail to Jackson, carrying the sacks on his back for most of the

distance.

. . . . . .

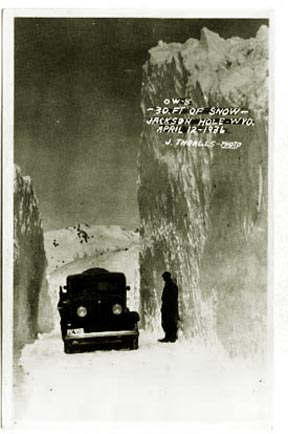

Left: Jackson Mail Stage, undated; Right: Thirty feet of Snow, Jackson, April 12, 1936.

Indeed, long distance telephone service into and out of Jackson had been problematical for some time.

The April 7, 1921, Jackson's Hole Courier noted the problems with the telephone service in a story about plans to

install a wireless telegraph receiving station. The paper noted that telephone communications were ofter

interrupted by Snake River washing out poles and breaking the line, snowslides doning the same thing in

Teton Pass, and wind storms blowing trees down on the lines. The plans called for a wireless telegraph station to

be installed in Victor. If it worked out, then a sending station would ultimately be installed in

Jackson.

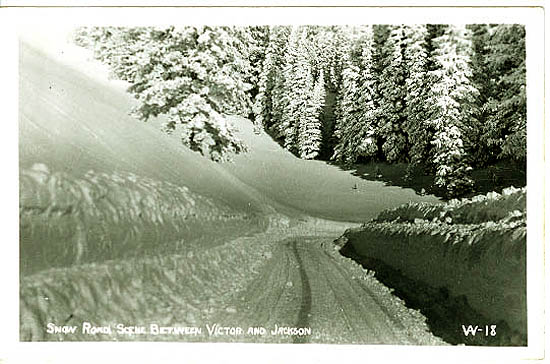

Jackson-Victor Road, undated, photo by Charles Wesley Andews.

Earlier, in 1912 or 1913 Elias Wilson's life was saved by one of his horses. When Wilson's team was overtaken by

a snowslide, one of the horses landed on top of him. The horse's head was above the snow. The horse lunged and kicked bringing

air down to Wilson and at the same time ultimately was able to free the two, not, however, without Wilson

being badly bruised and injured from the horse's kicks.

Traveling in Winter Jackson Hole, Wyoming, photo by

William P. Sanborn, 1930's.

.

During the winter, school children were transported to school in Jackson by means of a school sleigh.

School sleigh, undated..

Spring did not relieve delays in delivery of the mail. The June 10, 1920, edition of the

Courier noted that mail service into Jackson was interrupted. In the winter a temporary bridge over the Snake River

was utilized, but when spring came to prevent it from being swept away by the spring runoff, it was dismantled.

The river was too high to be forded and too rapid for a ferry upon which the mail could be entrusted.

Al Austin, undated.

The road through Hoback Canyon was hardly any better. In Hoback Canyon, Forest Ranger Al Austin was caught in one snowslide.

He survived and called the area the "Bull-of-the-Woods." In the winter, Austin patrolled the forest on homemade wooden

skis.

Winter could last late into the spring. The Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 18, 1933, p. 5, noted as an example that when

the wife of State Representative William C. Deloney of Jackson died, her relatives from Evanston were unable to attend the funeral

because of the condition of the roads through both Hoback Canyon and Teton Pass.

Today in the winter, the roads into the valley are still frequently closed for avalanche control by the Wyoming Department of

Transportation. One of the most dangerous avalanche areas in the state is an area in Hoback Canyon known as

"Cow-of-the-Woods" about 9 miles south of Jackson. Even in the summer, the road would often be blocked. Today, the road is still susceptable to being blocked by mud or rock slides.

Hoback Canyon, Winter 1935-1936.

For more on Hoback Canyon and John Hoback, see Pinedale and

Rendezvous.

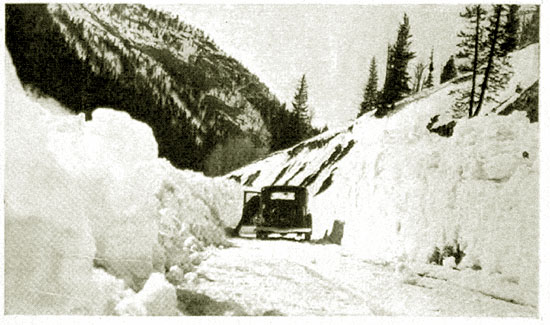

Teton Pass, 1946. Photo by William P. Sanborn.

Next Page: Jackson continued, Center Street, Roy Van Vleck, Jackson Mercantile, Mercill's Store.

|