| Photos Continued from previous page From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Fort Yellowstone, Nathaniel P. Langford, Henry D. Washburn, Truman C. Everts, "Yellowstone Jack" Baronett. |

|

| Photos Continued from previous page From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Fort Yellowstone, Nathaniel P. Langford, Henry D. Washburn, Truman C. Everts, "Yellowstone Jack" Baronett. |

|

|

|

|

About This Site |

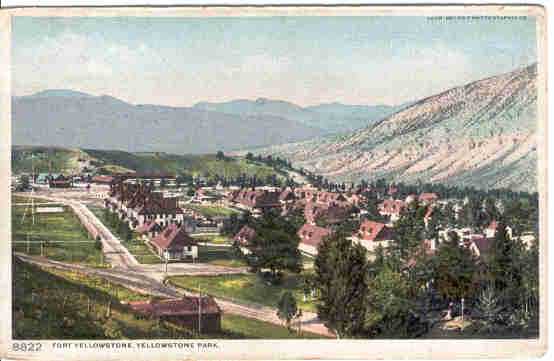

1. Hotel, 2. U.S. Engineer, 3. Bachelor Officers Quarters, 4. Captain's Quarters, 5. Field Officers' Quarters, 6. Cavalry Barracks, 7. Post Exchange, 8. Blacksmith, 9. Stables.

Fort Yellowstone, approx. 1905, Detroit Publishing Company. When Yellowstone was established as the nation's first national park in 1872, it was under the administration of the civilians who proved unable to perform the job. Congress, in disgust, in 1886 refused to appropriate any more funds for the administration of the park. Thus, the park was turned over to the military for administration. For the first five years, the military was stationed in temporary quarters. Permanent facilities were consructed in 1891.

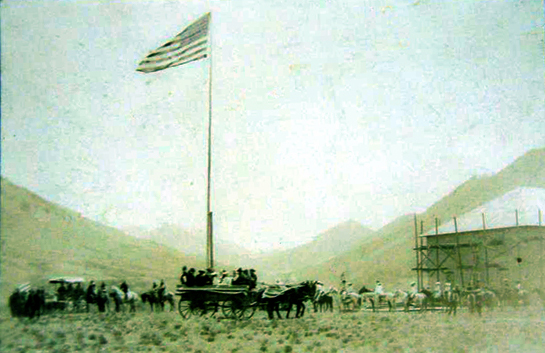

Fort Yellowstone, 1891. In defense of the civilians, however, it must be said that Congress had not been particularly generous. Indeed, the Park's first superintendent, Nathaniel P. Langford, received no salary during his five-year term. The result was that he visited the park only twice in the five years, once with the 1872 Hayden Expedition and later in 1874. The second superintendent, Philetus W. Norris fared slightly better with an appropriate of $10,000 per year for all costs of running the park.

Langford prior to his appointment as Superintendent had been actively involved in politics and his appointment might to some extent be regarded as a consolation prize for his tribulations in the war between President Andrew Johnson and Congress. First Johnson tried to remove him from his position as Collector of Internal Revenue and Congress overrode the removal. A compromise was reached whereby he resigned as Collector and would accept exile to Montana as governor. When President Johnson attempted to appoint Langford to the governorship, Congress refused to confirm, leaving Langford in Virginia City, then capital of Montana Territory, without a job. Langford, however, also had the advantage of having been a participant in the 1870 Washburn Expedition to the park and having actively promoted the creation of the Park. He was additionally related by marriage to two of the chief financial backers of the Jay Cooke's Northern Pacific. Jay Cooke pushed the creation of the park in order to create passengers for the Railroad. The Washburn Expedition of 1870, named after its leader Henry Dana Washburn (1832-1871), surveyor general of the Territory of Montana, is generally given credit for having inspired F. V. Hayden to organize his subsequent expedition. It has been noted that following the return of the Washburn Expedition to Helena, that Langford went on the lecture circuit. In the audience at one lecture was Hayden. Henry D. Washburn was born in Windor, Vermont, and moved to Indiana in 1850 where he practiced law. During the Civil War he fought at Vicksburg and later in Virginia including Cedar Creek. Upon his mustering out he was brevetted as a major general. He then served in Congress. He declined to run for reelection in 1868 and was appointed as surveyor-general of Montana. Mount Washburn, the highest point in the Park is named after him.

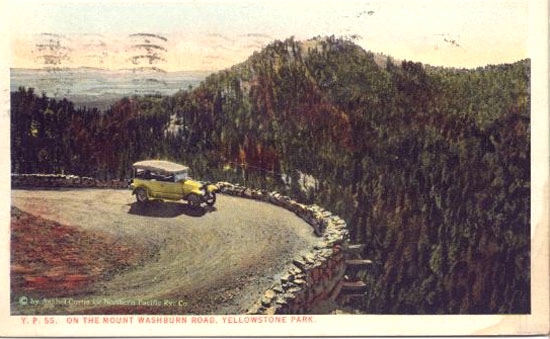

Road to Mount Washburn, 1933, photo by F. J. Haynes.

Yellowstone Jack (1827-1901?) was himself one of those larger than life colorful adventurers that young boys dreamed of becoming when reading dime novels. He was born into an apparently titled family in Scotland. He ran away to sea and jumped ship to join the California Gold Rush. Thereafter, he prospected for gold in Africa, Australia, and Colorado. He served as second mate on a whaling ship. He acted as a courier for Albert Sidney Johnston during the Mormon War. With the outbreak of the Civil War in enlisted in Confederate Forces in Texas. Later Baronett served with the Emperor Maximilian before coming to Montana in 1866. Not withstanding that he was a former Confederate, he served as a guide for George A. Custer and Philip H. Sheridan. He joined the gold rush to Nome, but his vessel was lost. In 1901, Baronett disappeared while traveling from Washington State to California. Six weeks after Baronett's disappearance word came that a relative had been killed in the Boer War and, if he could be found, Baronett had inherited the title. After thirty-seven days wandering in the wilderness, with no weapon, a lost shoe, snow, rain, forest fire, encounters with a mountain lion, and with wolves, and wearing nothing but the clothes he had when he became separated from the rest of his party, Everts was found by Baronett and Pritchett. In his 1871 account of his survival, "Thirty-Seven Days of Peril," Scribner's Monthly, November, 1871, Everts described his rescue: A solemn conviction that death was near, that at each pause I made my limbs would refuse further service, and that I should sink helpless and dying in my path, overwhelmed me with terror. Amid all this tumult of the mind, I felt that I had done all that man could do. I knew that in two or three days more I could effect my deliverance, and I derived no little satisfaction from the thought that, as I was now in the broad trail, my remains would be found, and my friends relieved of doubt as to my fate. Once only the though flashed across my mind that I should be saved, and I seemed to hear a whispered command to "struggle on." Groping along the side of a hill, I became suddently sensible of a sharp reflection, as of burnished steel. Looking up, through half closed eyes, two rough but kindly faces met my gaze.

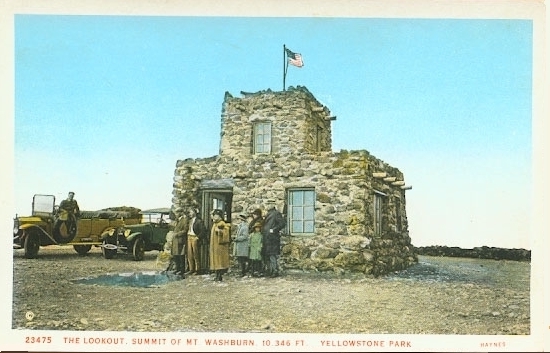

Top of Mount Washburn, 1920's, photo by F. Jay Haynes.

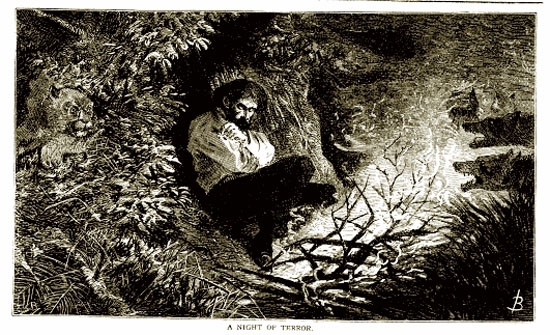

"A Night of Terror," Scribner's Monthly, Nov. 1871 And how did Everts become lost? At a time when he was riding separately from his companions, he had dismounted. His horse was startled and ran away bearing Everts' gun and supplies. Although the area was abundent with game, Everts had no weapon and, thus, survived on one small bird he caught and ate raw, several fish, and thistle roots. Night brought particular terrors. One night he was awakened by the sound of a mountain lion circling about a tree in which Everts had taken refuge. The sounds of the wolves also provided a terror. He began to halucinate and had imaginary companions and a guide. At one point, Everts' hunger was satiated by a dream of being in the finest restaurants of New York and Washington dining on plump sweet oysters. As indicated on the next page, twice he had to flee a forest fire. With the refusal of Congress to approprate any funds, the Department of the Interior called upon the military. Company M, First Cavalry from Ft. Custer was assigned to the post. In 1890 Congress appropriated $50,000 for the construction of buildings. The last building to be built by the military was the chapel, in 1913, after the pictures at the top of this page were taken. President Theodore Roosevelt recommended civilian control over Yellowstone and in 1912 his successor President Taft recommended that Congress appropriate funds to turn the park over to civilian control. The Act creating the National Park Service was adopted in 1916 during the Wilson Administration and in October of that year, the National Park service assumed administration. The resumption of civiliam control of the Park resulted in drastic changes. As indicated on the next page, large investments by the various concessionaires were required. Stages were replaced by "auto stages," operation of the hotels and campgrounds were consolidated. Prior to 1916 Park Hotels, campgrounds, and transportation were operated by a number of concessionaires. Hotels were operated by the Yellowstone Park Association with other hotels owned by Frank Jay Haynes. Tent campgrounds were operated by the Wylie Permanent Camping Company and by Shaw and Powell Camping Company. Each provided transportation and tours for their customers. Transportation was also provided by the Cody-Sylvan Pass Stagecoach Company of Pahaska, the Yellowstone and Monida Company from West Yellowstone and the Yellowstone Transportation Company of Gardiner.

In 1916, the Secretary of the Interior in his report noted that all of the National Parks were open to motor travel and observed that with the construction of roads the parks would become more available to the people. Indeed, by the 30's, automobile travel to Yellowstone became an important contribution to the economy of the state with "autocamps" being located in most cities. For a photo album of an auto tour from Lincoln, through Casper, Thermopolis, Cody and Yellowstone in 1937, visit Joycolyn Knapp's Photo Album. Mrs. Knapp maintained meticulous records of her expenses. In Yellowstone she observed that on August 31 it was necessary to drain the car's radiator due to the 18 degree weather.

|