| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Lacey Act, Pelican Creek, Obsidian Cliff, Johnson Gardner. |

|

| Photos From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: Lacey Act, Pelican Creek, Obsidian Cliff, Johnson Gardner. |

|

|

|

|

About This Site |

The above photo was taken by William Henry Jackson as a part of the Hayden Expedition of 1871. For more on the founding of Yellowstone as a park, see discussion of the Hayden Expedition. In his official journal Hayden noted the basis for the naming of Pelican Creek. The Creek, which flows out of the north end of Lake Yellowstone, was named in 1864 by a group of prospectors led by Adam "Horn" Miller. Supposedly, John C. Davis, seeking his evening repast mistakingly shot a pelican thinking it to be a goose. The "goose" came down in the water requiring Davis to swim out to get it and bring it to shore. Even after defeathering and skinning, however, the pelican proved to be unedible and was hung in a tree to be found by Miller. Miller was one of the developers of Cooke City, Mt., named after Jay Cooke, president of the Northern Pacific Railroad, in the futile hope that Cooke would run a spur line to the city.

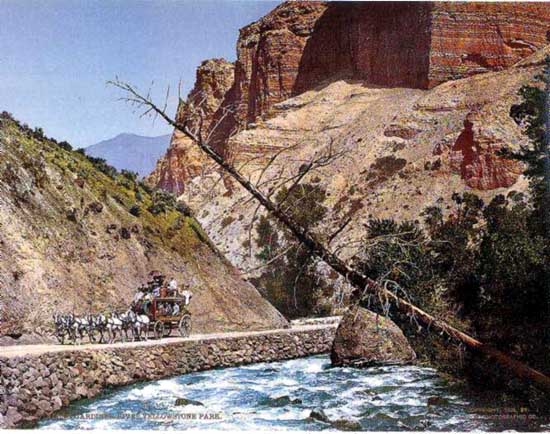

In 1897, William Henry Jackson became a member of the Detroit Publishing Company which acquired exclusive American rights to the Swiss "Photochrom" process invented in 1890 by Orell Fussli. The process used as many as 16 lithographic stones to produce color photographs from black-and-white originals. Detroit Publishing extolled the process: "The Results combine the truthfulness of a photograph with the color and richness of an oil painting or the delicate tinting of the most exquisite watercolor." The vividness of the process may be indicated by the view of the Gardner River below. By 1903, Jackson was the manager of Detroit Publishing and remained with the company until its insolvency in 1928. It was in the Pelican Valley in October of 1883 that soldiers caught Edgar Howell of Cooke City slaughtering five bison. Emerson Hough (1857-1923) was then writing for George Bird Grinnell's Forest and Stream for $15.00 a month. In the March 13, 1884, edition of the magazine he pointed out the absurdity of the penalties for poaching in Yellowstone. All that could be done was expel Howell from the Park only to have him return again. Hough reported that there were only about 100 bison left in the park. Public outrage resulted in the passage of the Lacey Act providing for real penalties for harming animals within the park. Hough later went on to write the Curly cowboy series in the Saturday Evening Post, Passing of the Frontier and The Covered Wagon, devoted to the Texas cattle trails and the Oregon Trail. As was Grinnell, Hough was a personal friend of Theodore Roosevelt.

Gardner River, Photochrom by Detroit Publishing Company, 1903. The Gardner River and Gardiner, Mont., are both named after early trapper Johnson Gardner. Gardner was associated with William H. Ashley's fur trading expeditions. In 1825, as a part of John Weber's brigade, Gardner was involved with a confrontation with the Hudson's Bay Company's Peter Skene Ogden in which, in essence, the Americans stole furs belonging to the outnumbered British. Later he worked as a "free" trapper in Montana with Pierre Trevanitagon, a deserter from the Hudson's Bay Company. Trappers who left owing the Company for supplies were regarded as "deserters." Gardner was also a part of Sublette, Bridger, and Jackson's Rocky Mountain Fur Company. Trevanitagon was killed by the Blackfeet in 1828. In 1832, trapper Hugh Glass was killed by Arikaras. Later, several Arikaras visited Gardner in his camp. Gardner recognized Glass's knife and other gear in the possession of two Indians. Gardner inflicted suitable punishment for the death of his fellow trapper. It was described by James Beckwourth in his Autobiography: When they came upon the scene, Crow Indians accompanying Beckwourth protested against the burning of the two Arikaras. The Crow wanted to scalp them first, before they were to be thrown into the flames alive. Gardner explained he wished to burn them up clean. In the early 1830's, Gardner trapped in the Yellowstone and was selling his furs to the American Fur Company. Gardner was captured by Arikaras. They had no compunctions as to burning clean. Gardner was scalped and burned alive.

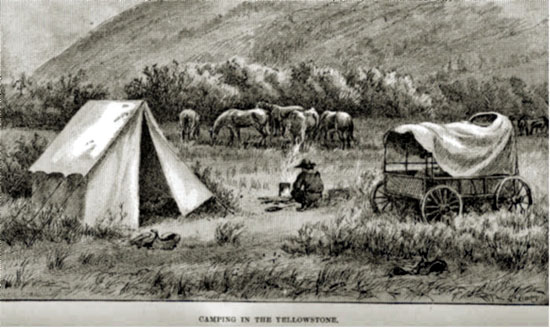

Camping in the Yellowstone, 1886 [Phillippics, a discourse full of acrimonious invective, so-called from the speeches of Demosthenes in which he railed against Philip II, King of Macedonia. Matutinal, morning.]

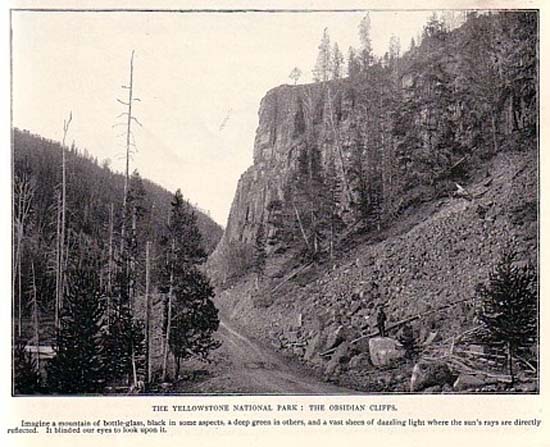

"THE YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK: THE OBSIDIAN CLIFFS. Imagine a mountain of bottle-glass, black in some aspects, a deep green in others, and a vast sheen of dazzling light where the sun's rays are directly reflected. It blinded our eyes to look upon it." The Illustrated American, October 18, 1890.

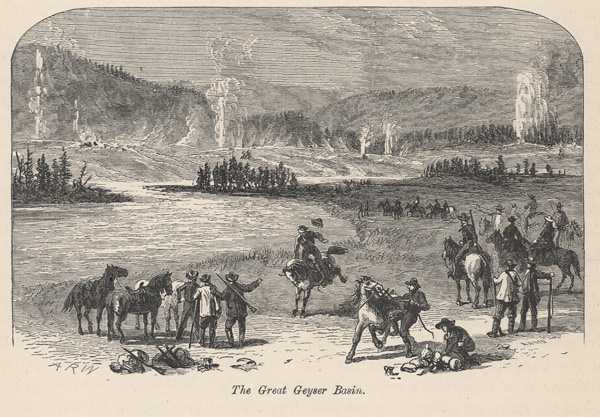

Geyser Basin, Firehole River, engraving based on sketch attributed to Alfred R. Waud The Firehole River takes its name not from the plumes of steam from the geysers or the hot springs, but was named by early trappers as a result the area being burned over by a forest fire. As indicated by the caption, the above engraving is attributed to Alfred R. Waud (1828-1891). Waud was born in London. There, he learned art as the designer of theatrical backdrops. He came to the United States in his twenties and was employed by the New York Illustrated News. He had an ability to make sketches directly on the blocks of wood used by the newspaper's engravers. During the Civil War and during Reconstruction he provided sketches to Harper's Weekly. Subsequently, he provided sketches of the Chicago Fire to the Every Saturday Magazine.

Next Page, Yellowstone continued. |