|

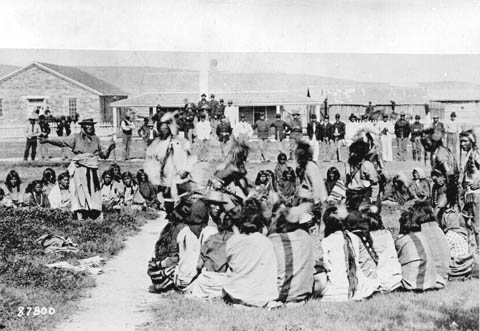

Fort Washakie, undated

In 1867, a gold rush started in the South Pass City area south of present day Lander. This in turn brought not only miners and

prospectors to South Pass City and Atlantic City but resulted in homesteaders settling

in the Wind River Basin. At the same time Indians had become a bit restless with attacks upon the settlers, freight trains, and,

indeed, part of South Pass City being burned down.

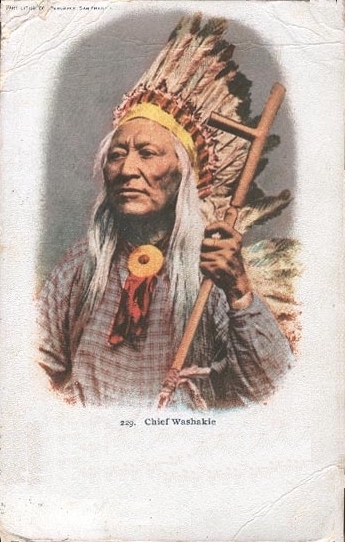

Chief Washakie, 1870

Chief Washakie, 1870

The closest military base was

at Fort Bridger over 150 miles to the southwest. Thus, the military found in necessary to

build military bases as outposts of Ft. Bridger. The first of the new forts was

Fort Stambaugh near South Pass City. In 1868, Camp Augur, named after Gen. Christopher Columbus

Augur commander of the Army's Department of the Platte, was established at present day Lander. In

short order the camp was renamed after Frederick H. Brown killed at the Fetterman massacre. In 1870,

the installation was moved to its present site to protect the Wind River Agency. Its need was illustrated by the

fact that attacks on travelers and settlers continued. Among those killed in 1869 were William Skinner, George

Colt, John G. Anderson, Mike Nenan. Others escaped by hiding. Sage Nickerson hid in the water

of Little Wind River, but the Indians killed his dog. Henry Lusk was wounded and his horses stolen.

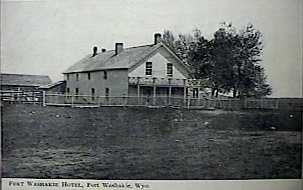

Ft. Washakie Hotel, 1909

Ft. Washakie Hotel, 1909

In 1870, among those killed were Franklin Irwin who survived the attack and was stripped bare by the Indians.

He managed to walk home where he expired. On the same day, March 31, as Irwin was attacked, William S. Bennington, James Othicks,

Eugene Fosbery, John McGuire, and Anson B. Kellogg were killed. In May the army engaged Indians on the

Big Beaver near Miners Delight. Lt. Stambough was killed. In June, Oliver Lamereaux was killed and Ed Young's

ranch was attacked. Ten days later on June 27, Dr. Barr, Harvaey Morgan and Jerone Mason were killed.

They were buried in the Camp Brown cemetery in what is now Lander. Morgan's

skull was later discovered during construction work in Lander. He was killed by having

his skull crushed with a wagon hammer. His skull is now on display in a museum. Knife marks indicate that he was

scalped. Other attacks continued over the

next sevral years.

In 1878, the fort was renamed after

Chief Washakie, father-in-law of Jim Bridger and an ally of the army against the Sioux.

Washakie was the only U.S. miltary installation named after an

American Indian Chief. Each state has two honorees in the National Statuary Hall in

Washington. Wyoming is represented by Esther Hobart Morris and by Chief Washakie. In

addition a statue of Washakie is in the Capitol Rotunda in Cheyenne.

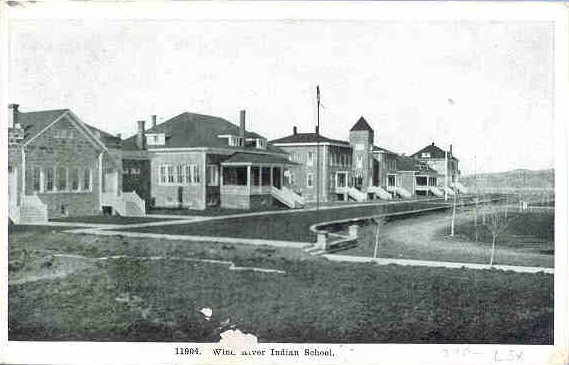

Indian School at Ft. Washakie, 1909

Chief Washakie's policies of accomodation with the Whites also included an insistance that

there be provided schools, hospitals, and other services.

Thus, in the Fort Bridger treaty of 1868 with the Shoshoni, the Government

pledged to establish a school at Fort Washakie at a cost of not more than $2,500. The first teacher

at Fort Washakie was James J. Chander (1849-1927). The first class has 35 students, both Indian and

white.

Chief Washakie continued support for education. He, among other things, donated 160 acres of irrigated

land to the Rev. Dr. John Roberts (1853-1949) for the establishment of the Shonshone Indian Mission

Boarding School.

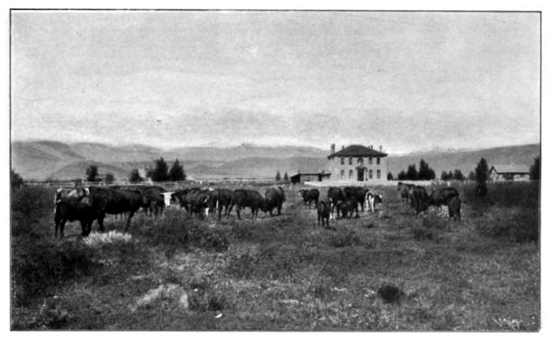

Shonshone Mission School near Ft. Washakie, approx. 1906.

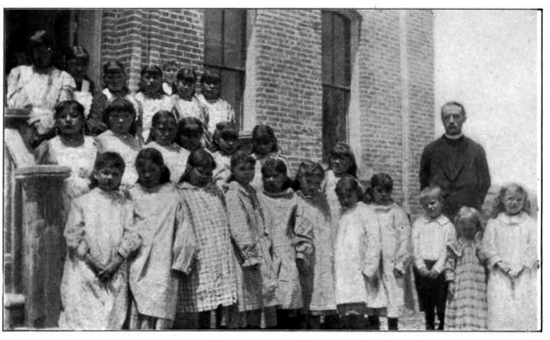

The Reverend Roberts is also credited with the establishment of the

Boarding School. The Reverend Roberts was born in Llellys, Flintshire, North Wales, and ordained in

Nassau, The Bahamas, before coming to Wyoming. He arrived in Lander on February 10, 1883, after a

8 day trip from Green River City in 60 degree below zero weather. In addition to the founding of the

two schools, the Rev. Roberts with Charles Lajoe translated portions of the Book of Common Prayer into

Shonshone. In recognition of his services to the Shonshone, he was bestowed the title of

"Elder Brother."

The Reverend John Roberts with students at the Mission School, approx. 1906.

In 1933, the Legislature of Wyoming recognized the accmplishments of the Reverend Roberts. The Reverend Roberts was for

a part of the time assisted by a full-blooded Arapaho Episcopal priest, the Reverend Doctor Sherman Coolidge. (1862-1932)

The Reverend Sherman Coolidge The Reverend Sherman Coolidge

When Coolidge (native name, "Runs on Top") was a young boy, his father, Bansada, ("Big Heart") was killed in a battle with the Army. Coolidge's

mother, Ba-ahnoce "Turtle Woman", then gave the young boy up to an army officer who in turn gave the young boy over to anther officer, Charles A. Coolidge,

who reared the young boy as his own. He expressed a desire to study for the holy orders and return to preach the Gospel to his

own people. He was, accordingly, sent to Shattuck School in Fairbault, Minnesota. There, the Right Reverend Henry Whipple took a personal

interest in the young boy. Following Shattuck, he received his theological studies at Seabury

Divinity School and later post-graduate studies at Hobart College. Before completing his studies at

Hobart he was ordained as a deacon and travelled to the Wind River Reservation. Upon his arrival there, an old

woman recognized him as her long lost son. Following the completion of his studies, Coolidge married Grace

Wetherbee who accompanied him to the Wind River Agency. She published a series of vignettes describing life on the

agency in Collier's weekly and the Outlook Magazine. These, with other descriptions, were published in 1917 as

Teepee Neighbors, Four Seas Press, Boston, 1917. They provide us with accounts of life on the Agency in the

early part of the Twentieth Century. To a modern reader, the accounts may seem depressing and bleak, describing as they

do the abject proverty, hunger, and constant death. Blindness caused by an

infectious eye disease, trachoma, plagued both the young and old. But through it all, the residents of the

agency took it as a part of life. Mrs. Coolidge explained:

By far the most harrowing fact of reservation life is the great, omnipresent, overwhelming and constant nearness of death. Indeed, death is no more at home on the

river Styx itself than with the boundary lines of the ordinary reservation.

* * * *

The Indian's attidtude toward death is interesting. Personally I found it both illuminating and inspring. He is not

civilized; that is, he is not a materialist -- for is not your so-called civilized Indian, the one who

lives in a house rather than a teepee, and who has given up his paint and nakedness for store-bought clothes? -- therefore he does not, as a axiom of conduct, use any and every expedient to keep the

breath in his body, -- and this regardless of the state of decrepitude of that body -- choosing life invariably rather than death. Indeed death is not to him the

castastrophe it is to the ordinary human produce of civilization. He is no fatalist like the

Oriental, but rather he regards the coming his last long sleep simply as he would the

approach of night or winter with their added but normal rigors. With his native dignity he meets it fairly in the

way. Nor is his mind compelled by fear. He is able to use his judgment in this greatest crisis as he would do in any other.

"If you have your leg amputated your life will be saved; if not, you will die." The doctor speaks; the interpreter,

probably one of the sick man's own children, makes the meaning plain. The man addressed smokes his

pipe slowly, considering. At length he draws the stem from his lips and looks up. "I will die," he says. And from the

moment of making his decision -- a natural, though none the less painful, one to his friends -- in his whole attidtude of mind he abides

calmly by his choice. His family do not try to deter him. The wisdom, also the finalty of his

decision, are undoubted.

No, the Indian has not the dread, the terror, the total aversion to death of the civilized man * * *.

Also depressing was the indifference by some to the Indian's plight. The Coolidges took one young girl to

Denver for treatment of trachoma. With treatment blindness could be prevented. The infection is highly contagious. Linens and towels exposed to

one suffering from the disease should not be used by others. Mrs. Coolidge requested that the Denver physician write a letter to

the physician at the Agency:

He laughed a little. "I'll write the letter," he said. "Anyhow he probably knows enough to realize that the

case is a serious one."

But we felt that we must understand more fully than this. "What if they should somehow neglect her and she should not be cured?"

He shrugged his sholders. "In that case," he said, "she'd go blind, that's all."

"So many do," we murmurmerd.

"Didn't your doctor up there look at her eyes, ever think they needed looking at, even?"

No."

He glanced at us a triffle incredulously.

There are lots of blind people on the reservation, children even."

He stared long at the child. "I can easily believe it."

The letter required that medication be given morning and night. The letter's instructions were that the

child should not sleep with others. Mrs. Coolidge inquired repeatedly of the little girl and

learned that the girl had been told to sleep with another girl because of the cold. Mrs. Coolidge protested to the

matron and was told:

"But they want to sleep together," she said. "They asked to. Beside that we're short of beds. And then also it saves bedding. The laundry girls are

awfully over-worked."

Mrs. Coolidge went to the doctor. He declined to speak to the matron. She went to the agent. He would not speak to the matron but, nevertheless, thanked

Mrs. Coolidge for her concern. By the end of the year, they were not giving the child the treatment at all. "'But why, Ethel?' 'I guess the bottle's empty.' she said."

In the 1920's the Reverend Coolidge was transferred to Denver where he became canon of the cathedral.

Chief Washakie (left, with hand extended) 1892 at Ft. Washakie

Chief Washakie, the last principal chief of the Shoshone, became chief in

1840. He served with 150 other Shoshone men under General Crook in the 1870's.

Sacajawea, who served as guide and interpreter for the Lewis and Clark

expedition and featured on the one dollar coin, served as Washakie's translator. In addition to English,

Sacajawea also spoke French, as did Chief Washakie.

Chief Washakie, approx. 1883-1885, photo by Baker & Johnston Studio, Evanston.

Chief Washakie, approx. 1883-1885, photo by Baker & Johnston Studio, Evanston.

Charles S. Baker and Eli Johnston* operated on an intermittent basis a photographic studio in Evanston and Rock Springs from

early 1881 through the late 1880's. A studio was also opened in Lander in 1892. The studio is today most famous for a series of

photographs of Shoshone and Arapaho in Wyoming, and Apache in Arizona including photographs from General Crook's Campaign against

Geronimo.

The colorized version photograph of Chief Washakie here was made by

a studio in San Francisco from the original made by Baker and Johnston. Baker and Johnston photographs from Arizona and New Mexico were made

in

1881, 1882, and 1885.

*Writer's note: The American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, shows "Johnston" as Eli Johnston, without showing

any biographical information for Johnston. That Johnston's first name was Eli is apparently based on

the 1880 Evanston census showing a photographer named Eli Johnson born in New York in

1860. Others have contended that Johnston refers to William J. Johnston of Rock Springs who maintained a photogrphic studio

in his own name in the 1890's. He is credited as the inventor of a panoramic camera in 1904.

In the photo to the left, Chief Washakie is holding a catlinite pipe with wooden

stem decorated with eagle feathers. Catlinite is a soft red pipestone which was obtained in

trade from Indians from Minnesota where it was mined from sacred quarries (Now Pipestone National

Monument) which were a gift from the Great Spirit. The quarries were made famous to the White Man in the opening

lines of the Song of Hiawatha:

On the Mountains of the Prairie,

On the great Red Pipe-stone Quarry,

Gitche Manito, the mighty,

He the Master of Life, descending,

On the red crags of the quarry

Stood erect, and called the nations,

Called the tribes of men together.

The stone is named after George Catlin (1796-1872) noted for his early

paintings of Plains Indians. In 1836, he was admitted to the quarries and furnished the first

depictions of the quarries and their significance:

At an ancient time the Great Spirit, in the form of a large bird,

stood upon the wall of rock and called all the tribes around him, and

breaking out a piece of the red stone formed it into a pipe and smoked it,

the smoke rolling over the whole multitude. He then told his red children

that this red stone was their flesh, that they were made from it, that

they must all smoke to him through it, that they must use it for nothing

but pipes: and as it belonged alike to all the tribes, the ground was

sacred, and no weapons must be used or brought upon it.

Sacajawea* died on April 9, 1884 and is buried along with her son, Brazil, at Ft. Washakie.

[*Writer's note: Lewis and Clark notes of their journey to the Pacific and back use some

14 different spellings for Sacajawea. Some scholars spell the name "Sacagawea." The spelling with a "g" is a Hidatsa spelling meaning "Bird Woman,"

a name given to her by the Hidatsa by whom she had been kidnapped.

The Shoshone spell her name Sacajawea. At Fort Washakie she used the name Porivo.]

Although

Sacagawea often wore a Jefferson medal such as carried by the Corps of Discovery, she infrequently spoke of the journey. It has been

speculated that this is because native Americans wished not to be reminded of the Expedition which

ultimately resulted in the loss of their way of life. It has been speculated by some that

the Sacajawea at Fort Washakie was not the interpreter for Lewis and Clark. Such speculation is, however,

based on the death of smallpox at Fort Mandan in 1812 of the wife of

Toussaint Charbonneau to whom Sacajawea had been sold. Charbonneau, however, had two wives and the name of the wife is not given in the

accounts of her death. Thus, there is a debate over Sacajawea and the "disgusting remarks" of Professor

Larson. (See letter from Ernest L. Newton to UWYO Magazine, Vol 2, No. 3.) The remarks, Larson, History of Wyoming:

"No outrageous tourist trap comes to mind, although erroneous information is

sometimes peddled. Visitors are sometimes told that a grave at Fort Washakie is the burial place

of Sacajawea of the Lewis and Clark expedition, when most scholars agree that

Sacajawea's grave is in South Dakota."

Larson, 2nd ed. revised, p. 532-533.

The memory and records of The Rev. Roberts, who officiated at Sacajawea's funeral

and, as noted by Mr. Newton, the personal knowledge of

the Rev. Roberts as to Sacajawea's son's education furnished by Capt. Merriweather Lewis; a twenty-year study by Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard; and a

report to the federal government by Dr. Charles A. Eastman (1858-1939), a Santee Sioux, all attest as

to Sacajawea's identity.

Chief Washakie died in 1900, over the age of 100, and was given full military honors

because of his service with the military. During World War II, liberty ship No. 0613 was named after him.

Reception for Pres. Arthur, Ft. Washakie, 1883,

photo by F. Jay Haynes. Reception for Pres. Arthur, Ft. Washakie, 1883,

photo by F. Jay Haynes.

In 1883 President Arthur toured Ft. Washakie, The Tetons and Yellowstone. The

party of 12, riding entirely by horseback, included a Lt. General, the Secretary of War and one United States

senator. Couriers were stationed every 20 miles with fresh horses to provide

communication for the presidential party to the "outside world".

Ft. Washakie Barracks, 1909

Ft. Washakie Barracks, 1909 The official

photographer for President Arthur's visit was F.Jay Haynes (1853-1921). Haynes maintained a successful business operating out of

a palace car on the Northern Pacific, later became an official photographer for

the Canadian Pacific taking pictures primarily in the area of Lake Winnipeg,

and eventually became the official photographer for Yellowstone Park in which position

he was succeeded by son, Jack Ellis Haynes (1884-1967). Jack and his wife had hoped that

the family business would continued to be carried out by their only child, Lida Haynes.

Unfortunately, she died in an automobile accident in 1952 at the age of 20. More than

24,000 glass and film negatives from the Haynes collection are now on deposit with

the Montana Historical Society. |